On the Commander-In-Chief Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major-General Jennie Carignan Enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in 1986

MAJOR-GENERAL M.A.J. CARIGNAN, OMM, MSM, CD COMMANDING OFFICER OF NATO MISSION IRAQ Major-General Jennie Carignan enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in 1986. In 1990, she graduated in Fuel and Materials Engineering from the Royal Military College of Canada and became a member of Canadian Military Engineers. Major-General Carignan commanded the 5th Combat Engineer Regiment, the Royal Military College in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, and the 2nd Canadian Division/Joint Task Force East. During her career, Major-General Carignan held various staff Positions, including that of Chief Engineer of the Multinational Division (Southwest) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that of the instructor at the Canadian Land Forces Command and Staff College. Most recently, she served as Chief of Staff of the 4th Canadian Division and Chief of Staff of Army OPerations at the Canadian Special OPerations Forces Command Headquarters. She has ParticiPated in missions abroad in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Golan Heights, and Afghanistan. Major-General Carignan received her master’s degree in Military Arts and Sciences from the United States Army Command and General Staff College and the School of Advanced Military Studies. In 2016, she comPleted the National Security Program and was awarded the Generalissimo José-María Morelos Award as the first in her class. In addition, she was selected by her peers for her exemPlary qualities as an officer and was awarded the Kanwal Sethi Inukshuk Award. Major-General Carignan has a master’s degree in Business Administration from Université Laval. She is a reciPient of the Order of Military Merit and the Meritorious Service Medal from the Governor General of Canada. -

AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser

ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser: Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, May 2019 June 2019: Admiral Sir Antony D. Radakin: First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, June 2019 (11/1965; 55) VICE-ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 February 2016: Vice-Admiral Sir Benjamin J. Key: Chief of Joint Operations, April 2019 (11/1965; 55) July 2018: Vice-Admiral Paul M. Bennett: to retire (8/1964; 57) March 2019: Vice-Admiral Jeremy P. Kyd: Fleet Commander, March 2019 (1967; 53) April 2019: Vice-Admiral Nicholas W. Hine: Second Sea Lord and Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, April 2019 (2/1966; 55) Vice-Admiral Christopher R.S. Gardner: Chief of Materiel (Ships), April 2019 (1962; 58) May 2019: Vice-Admiral Keith E. Blount: Commander, Maritime Command, N.A.T.O., May 2019 (6/1966; 55) September 2020: Vice-Admiral Richard C. Thompson: Director-General, Air, Defence Equipment and Support, September 2020 July 2021: Vice-Admiral Guy A. Robinson: Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Command, Transformation, July 2021 REAR ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 July 2016: (Eng.)Rear-Admiral Timothy C. Hodgson: Director, Nuclear Technology, July 2021 (55) October 2017: Rear-Admiral Paul V. Halton: Director, Submarine Readiness, Submarine Delivery Agency, January 2020 (53) April 2018: Rear-Admiral James D. Morley: Deputy Commander, Naval Striking and Support Forces, NATO, April 2021 (1969; 51) July 2018: (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Keith A. Beckett: Director, Submarines Support and Chief, Strategic Systems Executive, Submarine Delivery Agency, 2018 (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Malcolm J. Toy: Director of Operations and Assurance and Chief Operating Officer, Defence Safety Authority, and Director (Technical), Military Aviation Authority, July 2018 (12/1964; 56) November 2018: (Logs.) Rear-Admiral Andrew M. -

July 15, 2021 Vice Admiral John V. Fuller Office of the Naval Inspector

July 15, 2021 Vice Admiral John V. Fuller Office of the Naval Inspector General Via e-mail: [email protected] Dear Vice Admiral Fuller: I am writing on behalf of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and its more than 6.5 million members and supporters worldwide to urge you to investigate and pursue appropriate sanctions in accordance with the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), Articles 133-134, 10 U.S.C. §§ 933-934, against officers responsible for and military personnel participating in the cruel and unnecessary killing of animals in the annual joint military exercise known as Cobra Gold. Cobra Gold is conducted by multinational military forces, including, inter alia, the U.S. Marine Corps, which is administered by the U.S. Navy. PETA is submitting this complaint and calling on your office to fulfill its role as “the conscience of the Navy,” ensuring that it “maintain[s] the highest level of integrity and public confidence.”1 During Cobra Gold, Marines in Thailand kill chickens with their bare hands, skin and eat live geckos, and decapitate king cobras—a species vulnerable to extinction—in order to drink their blood as part of what the Marine Corps promotes, in some instances, as training in food procurement and, in other instances, as a comradery-building exercise. These acts, even if conducted for the purposes asserted by the military, are completely unnecessary, because proven effective alternatives to the use of live animals are available for the purported purpose of training in food procurement, and camaraderie-building is easily achieved through other activities associated with Cobra Gold that donot require members of the Marine Corps to engage in acts of gratuitous cruelty that reflect poorly on the Navy. -

Fm 6-02 Signal Support to Operations

FM 6-02 SIGNAL SUPPORT TO OPERATIONS SEPTEMBER 2019 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. This publication supersedes FM 6-02, dated 22 January 2014. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil/) and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard). *FM 6-02 Field Manual Headquarters No. 6-02 Department of the Army Washington, D.C., 13 September 2019 Signal Support to Operations Contents Page PREFACE..................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ vii Chapter 1 OVERVIEW OF SIGNAL SUPPORT ........................................................................ 1-1 Section I – The Operational Environment ............................................................. 1-1 Challenges for Army Signal Support ......................................................................... 1-1 Operational Environment Overview ........................................................................... 1-1 Information Environment ........................................................................................... 1-2 Trends ........................................................................................................................ 1-3 Threat Effects on Signal Support ............................................................................. -

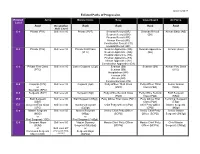

Enlisted Paths of Progression Chart

Updated 2/24/17 Enlisted Paths of Progression Enlisted Army Marine Corps Navy Coast Guard Air Force Level Rank Occupation Rank Rank Rank Rank Skill Level E-1 Private (PV1) Skill level 10 Private (PVT) Seaman Recruit (SR) Seaman Recruit Airman Basic (AB) Seaman Recruit (SR) (SR) Fireman Recruit (FR) Airman Recruit (AR) Construction Recruit (CR) Hospital Recruit (HR) E-2 Private (PV2) Skill level 10 Private First Class Seaman Apprentice (SA) Seaman Apprentice Airman (Amn) (PFC) Seaman Apprentice (SA) (SA) Hospital Apprentice (HA) Fireman Apprentice (FA) Airman Apprentice (AA) Construction Apprentice (CA) E-3 Private First Class Skill level 10 Lance Corporal (LCpl) Seaman (SN) Seaman (SN) Airman First Class (PFC) Seaman (SN) (A1C) Hospitalman (HN) Fireman (FN) Airman (AN) Constructionman (CN) E-4 Corporal (CPL) Skill level 10 Corporal (Cpl) Petty Officer Third Class Petty Officer Third Senior Airman or (PO3) Class (PO3) (SRA) Specialist (SPC) E-5 Sergeant (SGT) Skill level 20 Sergeant (Sgt) Petty Office Second Class Petty Office Second Staff Sergeant (PO2) Class (PO2) (SSgt) E-6 Staff Sergeant Skill level 30 Staff Sergeant (SSgt) Petty Officer First Class (PO1) Petty Officer First Technical Sergeant (SSG) Class (PO1) (TSgt) E-7 Sergeant First Class Skill level 40 Gunnery Sergeant Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Chief Petty Officer Master Sergeant (SFC) (GySgt) (CPO) (MSgt) E-8 Master Sergeant Skill level 50 Master Sergeant Senior Chief Petty Officer Senior Chief Petty Senior Master (MSG) (MSgt) (SCPO) Officer (SCPO) Sergeant (SMSgt) or or First Sergeant (1SG) First Sergeant (1stSgt) E-9 Sergeant Major Skill level 50 Master Gunnery Master Chief Petty Officer Master Chief Petty Chief Master (SGM) Sergeant (MGySgt) (MCPO) Officer (MCPO) Sergeant (CMSgt) or Skill level 60* or Command Sergeant (*For some fields, Sergeant Major Major (CSM) not all.) (SgtMaj) . -

Police Corporal - Patrol Department: Police Rev 03/14

City of Winder Job Description: Police Corporal - Patrol Department: Police Rev 03/14 EEO Function: Pay Grade: PD-6 EEO Category: Professional Status: Non-Exempt Pay Type: Hourly Position Number: 6346 I. Chain of Command/ Reports To Police Sergeant or through the Chain of Command to the Chief of Police II. Job Summary The functions of a Police Corporal are similar to that of a Police Officer with additional duties as an assistant supervisor or as a shift commander in the absence of a Sergeant. While incumbents are normally assigned to a specific geographic area for patrol, all functional areas of the law enforcement field, including investigation, administration, and training are included. A Police Corporal is also expected to perform field duties relating to response to emergencies, general and directed patrol, investigation of crimes and other non- criminal incidents, traffic enforcement and control, assisting in crime prevention activities, and other law enforcement services and duties as required. A significant degree of initiative, independent judgment, and discretion is required of incumbents to develop, maintain, and successfully perform supervisory tasks in a community oriented, problem solving approach to policing. III. Essential Duties and Functions • Follow and promote Policy & Procedures of the City of Winder. • Ensures that laws and ordinances are enforced and that the public peace and safety is maintained. • Responds to and resolves difficult and sensitive citizen inquiries and complaints. • Ensures the compliance of quality customer services to the public and internal City departments and employees. • Develops and maintains effective working relationships with the community. • Ensures that the department offers and maintains an effective and positive Community Oriented Policing philosophy for the purpose of maintaining the highest possible credibility level within the City. -

French Armed Forces Update November 2020

French Armed Forces Update November 2020 This paper is NOT an official publication from the French Armed Forces. It provides an update on the French military operations and main activities. The French Defense Attaché Office has drafted it in accordance with open publications. The French Armed Forces are heavily deployed both at home and overseas. On the security front, the terrorist threat is still assessed as high in France and operation “Sentinelle” (Guardian) is still going on. Overseas, the combat units are extremely active against a determined enemy and the French soldiers are constantly adapting their courses of action and their layout plans to the threat. Impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, the French Armed Forces have resumed their day-to-day activities and operations under the sign of transformation and modernization. DeuxIN huss arMEMORIAMds parachut istes tués par un engin explosif improvisé au Mali | Zone Militaire 09/09/2020 11:16 SHARE On September 5th, during a control operation within the Tessalit + region, three hussards were seriously injured after the explosion & of an Improvised Explosive Device. Despite the provision of + immediate care and their quick transportation to the hospital, the ! hussard parachutiste de 1ère classe Arnaud Volpe and + brigadier-chef S.T1 died from their injuries. ' + ( Après la perte du hussard de 1ere classe Tojohasina Razafintsalama, le On23 November 12th, during a routine mission in the vicinity of juillet, lors d’une attaque suicide commise avec un VBIED [véhicule piégé], le 1er Régiment de Hussards Parachutistes [RHP] a une nouvelle fois été Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, nine members of the Multinational endeuillé, ce 5 septembre. -

Staff Sergeant Ricky Hart Assistant Marine Officer Instructor NROTC Unit, the Citadel

Staff Sergeant Ricky Hart Assistant Marine Officer Instructor NROTC Unit, The Citadel Staff Sergeant Hart was born in Beaufort, South Carolina on 9 September, 1987. He enlisted in the Marine Corps in 2005 and attended recruit training with Fox Company, 2nd Recruit Training Battalion, Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, where he graduated as a meritorious Private First Class. Upon completion of recruit training in February of 2006, Staff Sergeant Hart reported to Marine Combat Training Battalion, Golf Company, and graduated in March of 2006. Staff Sergeant Hart was transferred to NAS Pensacola, where he attended Aviation Warfare Apprentice Training and Avionics Technician Intermediate Level Course, Class A1. While stationed at NAS Pensacola Staff Sergeant Hart was promoted to the rank of Lance Corporal and graduated his MOS at the top of his class. In October 2006, he was sent to his follow on MOS school aboard Keesler Air Force Base, Biloxi Mississippi. It was here Staff Sergeant Hart would learn his primary MOS of Precision Measurement Equipment (PME) Technician by completing General Purpose Electronic Test Equipment Repair and Calibration where he graduated at the top of his class. He also completed Intermediate Level Calibration of Physical/Dimensional and Measuring Systems school. In March of 2007, Staff Sergeant Hart received orders to his first duty station aboard MCAS New River, NC where he served as a Precision Measurement Equipment Technician within the MALS-29 Calibration Laboratory. In 2009 he was meritoriously promoted to the rank of Corporal and continued to serve with MALS-29. In August 2010, Staff Sergeant Hart re-enlisted in the Marine Corps and was transferred to MCAS Cherry Point, NC where he was assigned to MALS-14 and served as the Issue and Receive NCOIC for the Calibration Laboratory. -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

2Nd INFANTRY REGIMENT

2nd INFANTRY REGIMENT 1110 pages (approximate) Boxes 1243-1244 The 2nd Infantry Regiment was a component part of the 5th Infantry Division. This Division was activated in 1939 but did not enter combat until it landed on Utah Beach, Normandy, three days after D-Day. For the remainder of the war in Europe the Division participated in numerous operations and engagements of the Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe campaigns. The records of the 2nd Infantry Regiment consist mostly of after action reports and journals which provide detailed accounts of the operations of the Regiment from July 1944 to May 1945. The records also contain correspondence on the early history of the Regiment prior to World War II and to its training activities in the United States prior to entering combat. Of particular importance is a file on the work of the Regiment while serving on occupation duty in Iceland in 1942. CONTAINER LIST Box No. Folder Title 1243 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories January 1943-June 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories, July-October 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Histories, July 1944- December 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, July-September 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, October-December 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, January-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Casualty List, 1944-1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Journal, 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Narrative History, October 1944-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment History Correspondence, 1934-1936 2nd Infantry -

Not Another Constitutional Law Course: a Proposal to Teach a Course on the Constitution

Florida International University College of Law eCollections Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1991 Not Another Constitutional Law Course: A Proposal to Teach a Course on the Constitution Thomas E. Baker Florida International University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Thomas E. Baker, Not Another Constitutional Law Course: A Proposal to Teach a Course on the Constitution , 76 Iowa L. Rev. 739 (1991). Available at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications/173 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Not Another Constitutional Law Course: A Proposal to Teach a Course on the Constitutiont Thomas E. Baker* and James E. Viator** Justice Douglas once railed against law review writing in which "the views presented are those of special pleaders who fail to disclose that they are not scholars but rather people with axes to grind."l Not so here. Authors ofcourse materials, even casebook authors, package their biases in subtle but effective ways, through their selection, organization, and empha sis of materials. By this essay, which is based on the preface to our multilithed course materials, we mean to disclose our own biases to our students and readers. This is the basic question we consider at the outset: How is a course on the.Constitution different from a'course on constitutional law? Our course, "The Framers' Constitution," is about the history and theory of the t ©1991 Thomas E. -

Developing Senior Navy Leaders: Requirements for Flag Officer

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION the RAND Corporation. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Developing Senior Navy Leaders Requirements for Flag Officer Expertise Today and in the Future Lawrence M.