Executive Power, the Commander in Chief, and the Militia Clause

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

2Nd INFANTRY REGIMENT

2nd INFANTRY REGIMENT 1110 pages (approximate) Boxes 1243-1244 The 2nd Infantry Regiment was a component part of the 5th Infantry Division. This Division was activated in 1939 but did not enter combat until it landed on Utah Beach, Normandy, three days after D-Day. For the remainder of the war in Europe the Division participated in numerous operations and engagements of the Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe campaigns. The records of the 2nd Infantry Regiment consist mostly of after action reports and journals which provide detailed accounts of the operations of the Regiment from July 1944 to May 1945. The records also contain correspondence on the early history of the Regiment prior to World War II and to its training activities in the United States prior to entering combat. Of particular importance is a file on the work of the Regiment while serving on occupation duty in Iceland in 1942. CONTAINER LIST Box No. Folder Title 1243 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories January 1943-June 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories, July-October 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Histories, July 1944- December 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, July-September 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, October-December 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, January-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Casualty List, 1944-1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Journal, 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Narrative History, October 1944-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment History Correspondence, 1934-1936 2nd Infantry -

USASF Cheer Age Grid

2020-2021 USASF Cheer Age Grid All adjustments in RED indicate a change/addition since the previous season (2019-2020) All adjustments in BLUE indicate a change/addition since the early release in February 2020 We do not anticipate changes but reserve the right to make changes if needed. We will continue to monitor the fluidity of COVID-19 and reassess if need be to help our members. The USASF Cheer and Dance Rules, Glossary, associated Age Grids and Cheer Rules Overview (collectively the “USASF Rules Documents”) are copyright- protected and may not be disseminated to non-USASF members without prior written permission from USASF. Members may print a copy of the USASF Rules Documents for personal use while coaching a team, choreographing or engaging in event production, but may not distribute, post or give a third party permission to post on any website, or otherwise share the USASF Rules Documents. 1 Copyright © 2020 U.S. All Star Federation Released 1.11.21 -Effective 2020-2021 Season 2020-2021 Cheer Age Grid This document contains the division offerings for the 2020-2021 season in the following tiers: • All Star Elite • All Star Elite International • All Star Prep • All Star Novice • All Star FUNdamentals • All Star CheerABILITIES Exceptional Athletes (formerly Special Needs) The age grid provides a "menu" of divisions that may be offered by an individual event producer. An event producer does not have to offer every division listed. However, a USASF member event producer must only offer divisions from the age grids herein and/or combine/split divisions based upon the guidelines herein, unless prior written approval is received from the USASF. -

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations Updated July 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46236 SUMMARY R46236 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations July 6, 2020 Occupying almost half of South America, Brazil is the fifth-largest and fifth-most-populous country in the world. Given its size and tremendous natural resources, Brazil has long had the Peter J. Meyer potential to become a world power and periodically has been the focal point of U.S. policy in Specialist in Latin Latin America. Brazil’s rise to prominence has been hindered, however, by uneven economic American Affairs performance and political instability. After a period of strong economic growth and increased international influence during the first decade of the 21st century, Brazil has struggled with a series of domestic crises in recent years. Since 2014, the country has experienced a deep recession, record-high homicide rate, and massive corruption scandal. Those combined crises contributed to the controversial impeachment and removal from office of President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). They also discredited much of Brazil’s political class, paving the way for right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro to win the presidency in October 2018. Since taking office in January 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro has begun to implement economic and regulatory reforms favored by international investors and Brazilian businesses and has proposed hard-line security policies intended to reduce crime and violence. Rather than building a broad-based coalition to advance his agenda, however, Bolsonaro has sought to keep the electorate polarized and his political base mobilized by taking socially conservative stands on cultural issues and verbally attacking perceived enemies, such as the press, nongovernmental organizations, and other branches of government. -

The Role of Parliaments in the Semi-Presidential Systems: the Case of the Federal Assembly of Russia a Thesis Submitted to Th

THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTS IN THE SEMI-PRESIDENTIAL SYSTEMS: THE CASE OF THE FEDERAL ASSEMBLY OF RUSSIA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY RABĠA ARABACI KARĠMAN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF EURASIAN STUDIES OCTOBER 2019 DEDICATIONTASLAK I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Rabia Arabacı Kariman Signature : iii ABSTRACT THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTS IN THE SEMI-PRESIDENTIAL SYSTEMS: THE CASE OF THE FEDERAL ASSEMBLY OF RUSSIA Arabacı Kariman, Rabia M.Sc., Department of Eurasian Studies Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. IĢık KuĢçu Bonnenfant October 2019, 196 pages The purpose of this thesis is to scrutinize the role and status of the Federal Assembly of Russia within the context of theTASLAK semi-presidential system in the Russian Federation. Parliaments as a body incorporating the representative and legislative functions of the state are of critical importance to the development and stability of democracy in a working constitutional system. Since the legislative power cannot be thought separate from the political system in which it works, semi-presidentialism practices of Russia with its opportunities and deadlocks will be vital to understand the role of parliamentary power in Russia. The analysis of the the relationship among the constitutional bodies as stipulated by the first post-Soviet Constitution in 1993 will contribute to our understanding of the development of democracy in the Russian Federation. -

Digital Tools and the Derailment of Iceland's New Constitution

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Gylfason, Thorvaldur; Meuwese, Anne Working Paper Digital Tools and the Derailment of Iceland's New Constitution CESifo Working Paper, No. 5997 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Gylfason, Thorvaldur; Meuwese, Anne (2016) : Digital Tools and the Derailment of Iceland's New Constitution, CESifo Working Paper, No. 5997, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/145032 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Digital Tools and the Derailment of Iceland’s New Constitution Thorvaldur Gylfason Anne Meuwese CESIFO WORKING PAPER NO. -

The Aeronautical Division, US Signal Corps By

The First Air Force: The Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps By: Hannah Chan, FAA history intern The United States first used aviation warfare during the Civil War with the Union Army Balloon Corps (see Civil War Ballooning: The First U.S. War Fought on Land, at Sea, and in the Air). The lighter-than-air balloons helped to gather intelligence and accurately aim artillery. The Army dissolved the Balloon Corps in 1863, but it established a balloon section within the U.S. Signal Corps, the Army’s communication branch, during the Spanish-American War in 1892. This section contained only one balloon, but it successfully made several flights and even went to Cuba. However, the Army dissolved the section after the war in 1898, allowing the possibility of military aeronautics advancement to fade into the background. The Wright brothers' successful 1903 flight at Kitty Hawk was a catalyst for aviation innovation. Aviation pioneers, such as the Wright Brothers and Glenn Curtiss, began to build heavier-than-air aircraft. Aviation accomplishments with the dirigible and planes, as well as communication innovations, caused U.S. Army Brigadier General James Allen, Chief Signal Officer of the Army, to create an Aeronautical Division on August 1, 1907. The A Signal Corps Balloon at the Aeronautics Division division was to “have charge of all matters Balloon Shed at Fort Myer, VA Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum pertaining to military ballooning, air machines, and all kindred subjects.” At its creation, the division consisted of three people: Captain (Capt.) Charles deForest Chandler, head of the division, Corporal (Cpl.) Edward Ward, and First-class Private (Pfc.) Joseph E. -

This Index Lists the Army Units for Which Records Are Available at the Eisenhower Library

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. ARMY: Unit Records, 1917-1950 Linear feet: 687 Approximate number of pages: 1,300,000 The U.S. Army Unit Records collection (formerly: U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater: Selected After Action Reports, 1941-45) primarily spans the period from 1917 to 1950, with the bulk of the material covering the World War II years (1942-45). The collection is comprised of organizational and operational records and miscellaneous historical material from the files of army units that served in World War II. The collection was originally in the custody of the World War II Records Division (now the Modern Military Records Branch), National Archives and Records Service. The material was withdrawn from their holdings in 1960 and sent to the Kansas City Federal Records Center for shipment to the Eisenhower Library. The records were received by the Library from the Kansas City Records Center on June 1, 1962. Most of the collection contained formerly classified material that was bulk-declassified on June 29, 1973, under declassification project number 735035. General restrictions on the use of records in the National Archives still apply. The collection consists primarily of material from infantry, airborne, cavalry, armor, artillery, engineer, and tank destroyer units; roughly half of the collection consists of material from infantry units, division through company levels. Although the collection contains material from over 2,000 units, with each unit forming a separate series, every army unit that served in World War II is not represented. Approximately seventy-five percent of the documents are from units in the European Theater of Operations, about twenty percent from the Pacific theater, and about five percent from units that served in the western hemisphere during World War II. -

Presidential Or Parliamentary Does It Make a Difference? Juan J. Linz

VrA Democracy: Presidential or Parliamentary Does it Make a Difference? Juan J. Linz Pelatiah Pert Professor of Political and Social Sciences Yale University July 1985 Paper prepared for the project, "The Role of Political Parties in the Return to Democracy in the Southern Cone," sponsored by the Latin American Program of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and the World Peace Foundation Copyright © 1985 by Juan J. Linz / INTRODUCTION In recent decades renewed efforts have been made to study and understand the variety of political democracies, but most of those analyses have focused on the patterns of political conflict and more specifically on party systems and coalition formation, in contrast to the attention of many classical writers on the institutional arrangements. With the exception of the large literature on the impact of electorul systems on the shaping of party systems generated by the early writings of Ferdinand Hermens and the classic work by Maurice Duverger, as well as the writings of Douglas Rae and Giovanni Sartori, there has been little attention paid by political scientists to the role of political institutions except in the study of particular countries. Debates about monarchy and republic, parliamentary and presidential regimes, the unitary state and federalism have receded into oblivion and not entered the current debates about the functioning of democra-ic and political institutions and practices, including their effect on the party systems. At a time when a number of countries initiate the process of writing or rewriting constitu tions, some of those issues should regain salience and become part of what Sartori has called "political engineering" in an effort to set the basis of democratic consolidation and stability. -

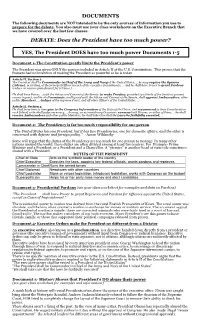

DOCUMENTS DEBATE: Does the President Have Too Much Power?

DOCUMENTS The following documents are NOT intended to be the only sources of information you use to prepare for the debate. You also must use your class worksheets on the Executive Branch that we have covered over the last few classes. DEBATE: Does the President have too much power? YES, The President DOES have too much power Documents 1-5 Document 1- The Constitution greatly limits the President’s power The President was given ONLY the powers included in Article II of the U.S. Constitution. This proves that the framers had no intention of making the President as powerful as he is today. Article II, Section 2 The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, … he may require the Opinion (Advice), in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, … and he shall have Power to grant Pardons (reduce or remove punishment) for [Crimes,] …. He shall have Power, …with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur (agree); and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers …, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, …: Article II, Section 3 He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such [ideas] as he shall judge necessary…; he may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, … he shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers; he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed, …. -

The U.S. Military's Force Structure: a Primer

CHAPTER 2 Department of the Army Overview when the service launched a “modularity” initiative, the The Department of the Army includes the Army’s active Army was organized for nearly a century around divisions component; the two parts of its reserve component, the (which involved fewer but larger formations, with 12,000 Army Reserve and the Army National Guard; and all to 18,000 soldiers apiece). During that period, units in federal civilians employed by the service. By number of Army divisions could be separated into ad hoc BCTs military personnel, the Department of the Army is the (typically, three BCTs per division), but those units were biggest of the military departments. It also has the largest generally not organized to operate independently at any operation and support (O&S) budget. The Army does command level below the division. (For a description of not have the largest total budget, however, because it the Army’s command levels, see Box 2-1.) In the current receives significantly less funding to develop and acquire structure, BCTs are permanently organized for indepen- weapon systems than the other military departments do. dent operations, and division headquarters exist to pro- vide command and control for operations that involve The Army is responsible for providing the bulk of U.S. multiple BCTs. ground combat forces. To that end, the service is orga- nized primarily around brigade combat teams (BCTs)— The Army is distinct not only for the number of ground large combined-arms formations that are designed to combat forces it can provide but also for the large num- contain 4,400 to 4,700 soldiers apiece and include infan- ber of armored vehicles in its inventory and for the wide try, artillery, engineering, and other types of units.1 The array of support units it contains. -

Types of Semi-Presidentialism and Party Competition Structures in Democracies: the Cases of Portugal and Peru Gerson Francisco J

TYPES OF SEMI-PRESIDENTIALISM AND PARTY COMPETITION STRUCTURES IN DEMOCRACIES: THE CASES OF PORTUGAL AND PERU GERSON FRANCISCO JULCARIMA ALVAREZ Licentiate in Sociology, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Peru), 2005. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in POLITICAL SCIENCE Department of Political Science University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Gerson F. Julcarima Alvarez, 2020 TYPES OF SEMI-PRESIDENTIALISM AND PARTY COMPETITION STRUCTURES IN DEMOCRACIES: THE CASES OF PORTUGAL AND PERU GERSON FRANCISCO JULCARIMA ALVAREZ Date of Defence: November 16, 2020 Dr. A. Siaroff Professor Ph.D. Thesis Supervisor Dr. H. Jansen Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. J. von Heyking Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. Y. Belanger Professor Ph.D. Chair, Thesis Examination Committee ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes the influence that the semi-presidential form of government has on the degree of closure of party competition structures. Thus, using part of the axioms of the so-called Neo-Madisonian theory of party behavior and Mair's theoretical approach to party systems, the behavior of parties in government in Portugal (1976-2019) and Peru (1980-1991 and 2001-2019) is analyzed. The working hypotheses propose that the president-parliamentary form of government promotes a decrease in the degree of closure of party competition structures, whereas the premier- presidential form of government promotes either an increase or a decrease in the closure levels of said structures. The investigation results corroborate that apart from the system of government, the degree of closure depends on the combined effect of the following factors: whether the president's party controls Parliament, the concurrence or not of presidential and legislative elections, and whether the party competition is bipolar or multipolar.