Julia Valeva

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Printing 600

REVUE BELGE DE NUMISMATIQUE ET DE SIGILLOGRAPHIE PUBLIÉE UITGEGEVEN SOUS LE HAUT PATRONAGE ONDER DE HOGE BESCHERMING DE S. M. LE ROI VAN Z. M. DE KONING PAR LA Doon HET SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE KONINKLIJK BELGISCH DE NUMISMATIQUE DE BELGIQUE GENOOTSCHAP VOOR NUMISIVIATIEK ET SUBSIDIÉE PAR LE EN :MET DE STEUN VAN DE GOUVERNgl\IENT REGEIUNG DIRECTEURS: PAUL NASTER, ÉMILE BROUETTE, JEAN JADûT, TONY HACKENS CXX - 1974. BHUXELLES BRUSSEL WILLIAM E. METCALF THE «CAIRO)} HOARD OF TETRARCHIC FOLLES (Planche 1) In March, 1914, the late E. T. Newell acquired a large hoard of tetrarchie folles from Hassan Abd-el-Salam, a Cairo dealer. Beyond the fact of its purchase at Cairo, nothing is known of the hoard's provenance; but this combines with the dominance of Alexandrian issues to suggest an Egyptian find spot. At an unknown date, Newell listed the contents of the hoard, describing types and legends and including references to Voetter's catalogue of the Gerin collection. About 1932 poorly preserved and duplicate specimens were removed from his trays; until recently, 400 such specimens remained in theîr original box and wrappings. Approxîmately 350 more pieces, aIl later issues of Alexandria, were discarded, sold, or lost ; they cannot now be located. It is possible to reconstruct the hoard fully from Newell's notes, though not in every case to identify pieces which came from it (1). Where his notes cau be checked against current ANS holdings, they are accurate; and despite the loss of many pieces which might have illuminated mint activity at Alexandria, the size and prove nance of the hoard warrant a record of its contents. -

The Developmentof Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrachs to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. The Development of Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrarchs to the Herakleian Dynasty General Introduction The emperor, as head of state, was the most important and powerful individual in the land; his official portraits and to a lesser extent those of the empress were depicted throughout the realm. His image occurred most frequently on small items issued by government officials such as coins, market weights, seals, imperial standards, medallions displayed beside new consuls, and even on the inkwells of public officials. As a sign of their loyalty, his portrait sometimes appeared on the patches sown on his supporters’ garments, embossed on their shields and armour or even embellishing their jewelry. Among more expensive forms of art, the emperor’s portrait appeared in illuminated manuscripts, mosaics, and wall paintings such as murals and donor portraits. Several types of statues bore his likeness, including those worshiped as part of the imperial cult, examples erected by public 1 officials, and individual or family groupings placed in buildings, gardens and even harbours at the emperor’s personal expense. -

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character J. Steven Davis Submitted to Dr. Jerry Sutton School of Divinity Liberty University September 19, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Research Proposal Abstract .............................................................................................................................11 Background ......................................................................................................................11 Limitations ........................................................................................................................18 Method of Research .........................................................................................................19 Thesis Statement ..............................................................................................................21 Outline ...............................................................................................................................21 Bibliography .....................................................................................................................27 Chapter II: Background of Athanasius An Influential Figure .......................................................................................................33 Early Life ..........................................................................................................................33 Arian Conflict ...................................................................................................................36 -

A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library CJ 237.H64 A handbook of Greek and Roman coins. 3 1924 021 438 399 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021438399 f^antilioofcs of glrcfjaeologj) anU Antiquities A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS G. F. HILL, M.A. OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COINS AND MEDALS IN' THE bRITISH MUSEUM WITH FIFTEEN COLLOTYPE PLATES Hon&on MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY l8 99 \_All rights reserved'] ©jcforb HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The attempt has often been made to condense into a small volume all that is necessary for a beginner in numismatics or a young collector of coins. But success has been less frequent, because the knowledge of coins is essentially a knowledge of details, and small treatises are apt to be un- readable when they contain too many references to particular coins, and unprofltably vague when such references are avoided. I cannot hope that I have passed safely between these two dangers ; indeed, my desire has been to avoid the second at all risk of encountering the former. At the same time it may be said that this book is not meant for the collector who desires only to identify the coins which he happens to possess, while caring little for the wider problems of history, art, mythology, and religion, to which coins sometimes furnish the only key. -

Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology

JOURNAL OF ANCIENT HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY JAHA Romanian Academy JOURNAL OF ANCIENT HISTORY Technical University Of Cluj-Napoca AND ARCHAEOLOGY Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14795/j.v1i2 ISSN 2360 – 266X ISSN–L 2360 – 266X No. 1.2 /2014 CONTENTS STUDIES REVIEWS ANCIENT HISTORY Victor Cojocaru Horaţiu Cociş ONCE MORE ABOUT ANTONIA TRYPHAINA 3 RADU OLTEAN, DACIA. THE ROMAN WARS.VOLUME I. SARMIZEGETUSA ..............................................57 Dragoș MITROFAN THE ANTONINE PLAGUE IN DACIA AND MOESIA INFERIOR 9 Csaba Szabó KREMER, GABRIELLE (MIT BEITRÄGEN VON CHRISTIAN GUGL, CHRISTIAN UHLIR UND MICHAEL Olivier Hekster UNTERWURZACHER), GÖTTERDARSTELLUNGEN, ALTERNATIVES TO KINSHIP? KULT – UND WEIHEDENKMÄLER AUS CARNUNTUM......59 TETRARCHS AND THE DIFFICULTIES OF REPRESEN- TING NON-DYNASTIC RULE 14 Imola Boda ARCHAEOLOGICAL MATERIAL RADA VARGA, THE PEREGRINI OF ROMAN DACIA (106–212) 61 Vitalie Bârcă RETURNED FOOT EXTERIOR CHORD BROOCHES Gaspar Răzvan Bogdan MADE OF A SINGLE METAL PIECE (TYPE ALMGREN C. GĂZDAC, F. HUMER, LIVING BY T HE COINS. 158) RECENTLY DISCOVERED IN THE WESTERN ROMAN LIFE IN THE LIGHT OF COIN FINDS PLAIN OF ROMANIA. NOTES ON ORIGIN AND AND ARCHAEOLOGY WITHIN A RESIDENTIAL CHRONOLOGY 21 QUARTER OF CARNUNTUM ..................................63 Silvia Mustață, Iosif Vasile Ferencz, Cristian Dima A ROMAN THIN-CAST BRONZE SAUCEPAN FROM THE DACIAN FORTRESS AT ARDEU (HUNEDOARA Florin Fodorean COUNTY, ROMANIA) 40 Z. CZAJLIK, A. BÖDŐCS (EDS.), AERIAL ARCHAEOLOGY AND REMOTE SENSING FROM THE BALTIC TO THE ADRIATIC. SELECTED PAPERS OF THE ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE AERIAL TH TH DIGITAL ARCHAEOLOGY ARCHAEOLOGY RESEARCH GROUP, 13 – 15 OF SEPTEMBER 2012, BUDAPEST, HUNGARY 65 Ionuț Badiu, Radu Comes, Zsolt Buna Xenia-Valentina Păușan CREATION AND PRESERVATION OF DIGITAL R. -

Roman Coins Elementary Manual

^1 If5*« ^IP _\i * K -- ' t| Wk '^ ^. 1 Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google Digitized by Google PROTAT BROTHERS, PRINTBRS, MACON (PRANCi) Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL COMPILED BY CAV. FRANCESCO gNECCHI VICE-PRBSIDENT OF THE ITALIAN NUMISMATIC SOaETT, HONORARY MEMBER OF THE LONDON, BELGIAN AND SWISS NUMISMATIC SOCIBTIES. 2"^ EDITION RKVISRD, CORRECTED AND AMPLIFIED Translated by the Rev<> Alfred Watson HANDS MEMBF,R OP THE LONDON NUMISMATIC SOCIETT LONDON SPINK & SON 17 & l8 PICCADILLY W. — I & 2 GRACECHURCH ST. B.C. 1903 (ALL RIGHTS RF^ERVED) Digitized by Google Arc //-/7^. K.^ Digitized by Google ROMAN COINS ELEMENTARY MANUAL AUTHOR S PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION In the month of July 1898 the Rev. A. W. Hands, with whom I had become acquainted through our common interests and stud- ieSy wrote to me asking whether it would be agreeable to me and reasonable to translate and publish in English my little manual of the Roman Coinage, and most kindly offering to assist me, if my knowledge of the English language was not sufficient. Feeling honoured by the request, and happy indeed to give any assistance I could in rendering this science popular in other coun- tries as well as my own, I suggested that it would he probably less trouble ii he would undertake the translation himselt; and it was with much pleasure and thankfulness that I found this proposal was accepted. It happened that the first edition of my Manual was then nearly exhausted, and by waiting a short time I should be able to offer to the English reader the translation of the second edition, which was being rapidly prepared with additions and improvements. -

When Did Diocletian Die? Ancient Evidence for an Old Problem

WHEN DID DIOCLETIAN DIE? ANCIENT EVIDENCE FOR AN OLD PROBLEM Mats Waltré March 2011 1 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Purpose ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Sources .................................................................................................................................................... 3 And what do contemporary sources tell? ........................................................................................... 5 Recent discussion - 311 or 312? .............................................................................................................. 7 Constantine and Lactantius ................................................................................................................. 7 C.Th. xiii, 10, 2 ..................................................................................................................................... 7 When did Diocletian die? New evidence for an old problem ............................................................. 9 Maxentius and Diocletian .................................................................................................................... 9 Ancient evidence ................................................................................................................................... 10 Lactantius -

The Persecution of Licinius

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1999 The persecution of licinius Gearey, James Richard Gearey, J. R. (1999). The persecution of licinius (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/14363 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25021 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Persecution of Licinius by James Richard Gearey A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF GREEK, LATIN AND ANCIENT HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA JUNE, 1999 Wames Richard Gearey 1999 National Library Biblioth&que nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Sweet 395. me Wellington Ottawa ON K 1A ON4 OltewaON KIAW Canada Canada YarrNI VOV.~ Our im Mr. mIk.nc. The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

Imperial Women and the Evolution of Succession Ideologies in the Third Century

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School July 2020 Embodying the Empire: Imperial Women and the Evolution of Succession Ideologies in the Third Century Christina Hotalen University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Scholar Commons Citation Hotalen, Christina, "Embodying the Empire: Imperial Women and the Evolution of Succession Ideologies in the Third Century" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8452 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Embodying the Empire: Imperial Women and the Evolution of Succession Ideologies in the Third Century by Christina Hotalen A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Julie Langford, Ph.D. William Murray, Ph.D. Sheramy Bundrick, Ph.D. Matthew King, Ph.D. Alex Imrie, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 2, 2020 Keywords: Numismatics, Epigraphy, Material Culture, Digital Humanities Copyright © 2020, Christina Hotalen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is quite an understatement to say that it takes a village to write a dissertation. This was written during a global pandemic, civic unrest, and personal upheavals. However, to quote a dear friend, “non bellum, sed completum est.” I could not have ventured into and finished such a monumental undertaking, and at such a time, without my very own village. -

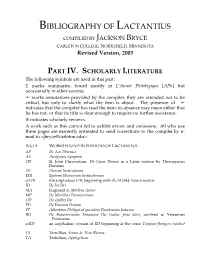

BIBLIOGRAPHY of LACTANTIUS COMPILED by JACKSON BRYCE CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA Revised Version, 2003

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF LACTANTIUS COMPILED BY JACKSON BRYCE CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA Revised Version, 2003 PART IV. SCHOLARLY LITERATURE The following symbols are used in this part: ∑ marks summaries, found mostly in L’Année Philologique [APh] but occasionally in other sources. + marks annotations provided by the compiler; they are intended not to be critical, but only to clarify what the item is about. The presence of + indicates that the compiler has read the item; its absence may mean either that he has not, or that its title is clear enough to require no further assistance. ® indicates scholarly reviews. A work such as this cannot fail to exhibit errors and omissions. All who use these pages are earnestly entreated to send corrections to the compiler by e- mail to <[email protected]>. SIGLA WORKS FOUND IN EDITIONS OF LACTANTIUS AP De Ave Phoenice AS Aenigmata Symposii CD St. John Chrysostom, De Cœna Domini in a Latin version by Hieronymus Donatus DI Divinae Institutiones EDI Epitome Divinarum Institutionum acEDI the acephalous EDI, beginning with ch. 51 [56], Nam si iustitia ID De Ira Dei MA fragment de Motibus Animi MP De Mortibus Persecutorum OD De Opifico Dei PD De Passione Domini PT Adhortatio Philippi ad quendam Theodosium Iudæum RD De Resurrectionis Dominicæ Die (Salve, festa dies), ascribed to Venantius Fotunatus acRD an acephalous version of RD beginning at the verse Tempora florigero rutilant … TS Tertullian, Sermo de Vita Æterna TA Tertullian, Apologeticus J. BRYCE, Bibliography of Lactantius, revised 2003 Part IV. Scholarly Literature 2 VM Lorenzo Valla, De Mystero Eucharistiæ The following subtitles for the seven books of DI are often found: I. -

Part I the Byzantine Empire

A TALE OF TWO EMPIRES: PART I THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE LECTURE I FOUNDATION: FROM BYZANTIUM TO CONSTANTINOPLE LECTURE II RECONQUEST: JUSTINIAN AND THE GOLDEN AGE LECTURE III DECLINE AND RESURGENCE: THE MACEDONIANS LECTURE IV THE ARRIVAL AND CONQUESTS OF THE SELJUK TURKS LECTURE V BYZANTINES, TURKS AND CRUSADERS LECTURE VI BYZANTINE ART AND ARCHITECTURE Copyright © 2007 by Dr. William J. Neidinger, Stylus Productions and The Texas Foundation For Archaeological & Historical Research FOUNDATION: FROM BYZANTIUM TO CONSTANTINOPLE I. INTRODUCTION - Byzantine and Ottoman Empires traditionally taught as two separate studies - compartmentalized and specialized nature of humanities today - their stories form a continuum - empires came to rule over the same peoples - empires faced many of the same enemies - empires came to accommodate these defeated enemies within their spheres - empires developed universalist mythologies for their respective religions - both served as mercenaries for the other - both at one time allied to one another - at one time imperial families intermarried - Imaret of Nilüfer Hatun, Nicaea (Iznik, Turkey) - 1346 Theodora marries Orhan; Nilüfer Hatun - remains Christian; regent while Orhan away at war - mother of Sultan Murad I (Moslem) - 1388 Imaret built by Murad I - both occupied the same imperial city: Byzantium, New Rome, Constantinople, Istanbul II. THE IMPERIAL CITY - capital of three empires: Roman / Byzantine, Latin Kingdom of the East, Ottoman Turkish - modern assessment of the city by the land: hills, valleys, buildings & walls - ancient assessment of the city by the waters: Golden Horn, Sea of Marmara, Bosphorus - strategic location: bridge between Europe & Asia and Black Sea & Mediterranean Sea - 667 BC Byzas of Megara consults Delphi re: foundation of a colony - “…opposite the blind…” and Chalcedon - acropolis beneath Tokapi Sarai - mercantile depot, repair center; fish; wine - 512-479 BC Persian occupation - 5th – 4th c. -

The Tetrarchy and the Last Persecution of Christians (303 – 311)

Received: October 24, 2017│Accepted: December 01, 2017 LIFE AND DEATH IN THE ANCIENT WORLD: THE TETRARCHY AND THE LAST PERSECUTION OF CHRISTIANS (303 – 311) Cláudio Umpierre Carlan1 Resumo O artigo começa com uma descrição do mundo romano após a Tetrarquia, com a luta pelo poder entre Constantino e, mais tarde, Licínio. Analisamos as questões políticas relativas ao mundo romano durante o período. Usando como fonte iconográfica a coleção numismática do acervo do Museu Histórico Nacional / RJ, utilizamos a imagem como uma fonte de propaganda, legitimando o poder imperial. Palavras-chave Moeda; império; iconografia; poder; símbolo. Abstract The present paper begins with a description of the Roman world after the Tetrarchy, with the fight for power between Constantine and, later, Licinius. We analyzed the political matters concerning the Roman world during this period. The numismatic collection stored at the Museu Histórico Nacional (National Historical Museum – MHN) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, served as an iconographic source to show how images were used at that time as propaganda, supporting and legitimizing the imperial rule. Key-words Coins; empire; iconography; power; symbol. 1 Assistant Professor, Federal University of Alfenas – Alfenas, MG, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] Heródoto, Unifesp, Guarulhos, v. 3, n. 1, Março, 2018. p.422-430 - 422 - Introduction With the death of Emperor Alexander Severus, murdered by his soldiers in 235, the period known as crisis of the third century begins in Rome. The crisis reaches all the levels of the Empire; political, social and economic. There was a first moment, referred to as Military Anarchy (235 – 268), in which the emperors were appointed by their soldiers, and killed soon after that.