The House of Austrian History a Press Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Society Trip to Prague and Vienna, 2018

History Society trip to Prague and Vienna, 2018 As one of the Trip Officers for the Edinburgh University History Society, Student Ambassador Carmen was responsible for organising a trip to Budapest and Vienna for 40 society members during Innovative Learning Week. While we were only away for 5 days, it felt like ages because we did so much in both cities! – Carmen Day 1: Monday, 19th of February Our flight to Budapest was extremely early – but this meant we got there really early too, giving us plenty of time to get our bearings! While the sky was blue, it was freezing cold as we walked around streets on the Pest side of the city, taking in the amazing views of Liberty Square & Parliament Square. After giving everyone a few hours to have dinner (and a nap after a long day of travelling!), we met up again to see the iconic Hungarian Parliament building light up at night. Here, we were able to get a big group photo, before running off to take some night shots of the stunning view over the River Danube! Day 2: Tuesday, 20th of February On our second day, we walked along the Széchenyi Chain Bridge (covered in snow!) to go across the Danube to Buda Castle. Using our trusty Budapest Cards, we were able to get a free Castle bus that took us outside the building – a lifesaver considering it was a very uphill walk! Some of our group were lucky enough to see the changing of the guard at the Sándor Palace, the residence of the Hungarian President. -

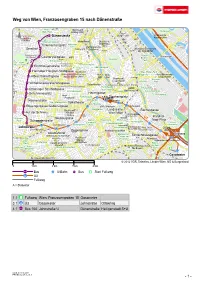

Footpath Description

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

Leistbaren Wohnraum Schaffen – Stadt Weiter Bauen

Stadtpunkte Nr 25 Ernst Gruber, Raimund Gutmann, Margarete Huber, Lukas Oberhuemer (wohnbund:consult) LEISTBAREN WOHNRAUM SCHAFFEN – STADT WEITER BAUEN Potenziale der Nachverdichtung in einer wachsenden Stadt: Herausforderungen und Bausteine einer sozialverträglichen Umsetzung Jänner 2018 AK STADTPUNKTE 25 ■ Alle aktuellen AK Publikationen stehen zum Download für Sie bereit: wien.arbeiterkammer.at/service/publikationen Der direkte Weg zu unseren Publikationen: ■ E-Mail: [email protected] ■ Bestelltelefon: +43-1-50165 13047 Bei Verwendung von Textteilen wird um Quellenangabe und um Zusendung eines Belegexemplares an die Abteilung Kommunalpolitik der AK Wien ersucht. Impressum Medieninhaber: Kammer für Arbeiter und Angestellte für Wien, Prinz-Eugen-Straße 20–22, 1040 Wien Offenlegung gem. § 25 MedienG: siehe wien.arbeiterkammer.at/impressum Zulassungsnummer: AK Wien 02Z34648 M ISBN: 978-3-7063-0708-6 AuftraggeberInnen: AK Wien, Kommunalpolitik Fachliche Betreuung: Christian Pichler und Judith Wittrich Autoren: Margarete Huber, Ernst Gruber, Raimund Gutmann, Lukas Oberhuemer (wohnbund:consult) Grafik Umschlag und Druck: AK Wien Verlags- und Herstellungsort: Wien © 2018 bei AK Wien Stand Jänner 2018 Im Auftrag der Kammer für Arbeiter und Angestellte für Wien Ernst Gruber, Raimund Gutmann, Margarete Huber, Lukas Oberhuemer (wohnbund:consult) LEISTBAREN WOHNRAUM SCHAFFEN – STADT WEITER BAUEN Potenziale der Nachverdichtung in einer wachsenden Stadt: Herausforderungen und Bausteine einer sozialverträglichen Umsetzung Jänner 2018 VORWORT In einer -

Online Zeitungen Im Vergleich

Vergleich österreichischer Online-Zeitungen und Magazine Projektleitung: Mag. Norbert Zellhofer Studien-Zeitraum: August-September 2006 Mehr Nutzen durch USABILITY. Praterstrasse. 33/12, 1020 Wien Tel: 1/204 86 50, Fax: 1/2048654 [email protected] http://www.usability.at Vergleich österreichischer Online-Zeitungen und Magazine Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ......................................................................... 2 Einleitung .................................................................................... 6 Tageszeitungen ............................................................................ 9 Die Presse: www.diePresse.com ................................................ 10 Der Standard: www.derstandard.at............................................ 11 Oberösterreichische Nachrichten: www.nachrichten.at .................. 11 Tiroler Tageszeitung: www.tirol.com .......................................... 11 Kleine Zeitung: www.kleine.co.at............................................... 11 Salzburger Nachrichten: www.salzburg.com ................................ 11 Wiener Zeitung: www.wienerzeitung.at ...................................... 11 Kurier: www.kurier.at .............................................................. 11 Österreich: www.oe24.at.......................................................... 11 Wirtschaftsblatt: www.wirtschaftsblatt.at .................................... 11 Heute: www.heute.at............................................................... 11 Neue Kärntner Tageszeitung: -

Notes of Michael J. Zeps, SJ

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History Department 1-1-2011 Documents of Baudirektion Wien 1919-1941: Notes of Michael J. Zeps, S.J. Michael J. Zeps S.J. Marquette University, [email protected] Preface While doing research in Vienna for my dissertation on relations between Church and State in Austria between the wars I became intrigued by the outward appearance of the public housing projects put up by Red Vienna at the same time. They seemed to have a martial cast to them not at all restricted to the famous Karl-Marx-Hof so, against advice that I would find nothing, I decided to see what could be found in the archives of the Stadtbauamt to tie the architecture of the program to the civil war of 1934 when the structures became the principal focus of conflict. I found no direct tie anywhere in the documents but uncovered some circumstantial evidence that might be explored in the future. One reason for publishing these notes is to save researchers from the same dead end I ran into. This is not to say no evidence was ever present because there are many missing documents in the sequence which might turn up in the future—there is more than one complaint to be found about staff members taking documents and not returning them—and the socialists who controlled the records had an interest in denying any connection both before and after the civil war. Certain kinds of records are simply not there including assessments of personnel which are in the files of the Magistratsdirektion not accessible to the public and minutes of most meetings within the various Magistrats Abteilungen connected with the program. -

List of Brands

Global Consumer 2019 List of Brands Table of Contents 1. Digital music 2 2. Video-on-Demand 4 3. Video game stores 7 4. Digital video games shops 11 5. Video game streaming services 13 6. Book stores 15 7. eBook shops 19 8. Daily newspapers 22 9. Online newspapers 26 10. Magazines & weekly newspapers 30 11. Online magazines 34 12. Smartphones 38 13. Mobile carriers 39 14. Internet providers 42 15. Cable & satellite TV provider 46 16. Refrigerators 49 17. Washing machines 51 18. TVs 53 19. Speakers 55 20. Headphones 57 21. Laptops 59 22. Tablets 61 23. Desktop PC 63 24. Smart home 65 25. Smart speaker 67 26. Wearables 68 27. Fitness and health apps 70 28. Messenger services 73 29. Social networks 75 30. eCommerce 77 31. Search Engines 81 32. Online hotels & accommodation 82 33. Online flight portals 85 34. Airlines 88 35. Online package holiday portals 91 36. Online car rental provider 94 37. Online car sharing 96 38. Online ride sharing 98 39. Grocery stores 100 40. Banks 104 41. Online payment 108 42. Mobile payment 111 43. Liability insurance 114 44. Online dating services 117 45. Online event ticket provider 119 46. Food & restaurant delivery 122 47. Grocery delivery 125 48. Car Makes 129 Statista GmbH Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel. +49 40 2848 41 0 Fax +49 40 2848 41 999 [email protected] www.statista.com Steuernummer: 48/760/00518 Amtsgericht Köln: HRB 87129 Geschäftsführung: Dr. Friedrich Schwandt, Tim Kröger Commerzbank AG IBAN: DE60 2004 0000 0631 5915 00 BIC: COBADEFFXXX Umsatzsteuer-ID: DE 258551386 1. -

Herbert Haupt, Der Heldenplatz (2000)

Demokratiezentrum Wien Onlinequelle: www.demokratiezentrum.org Printquelle: in: Douer, Alisa (Hg.): Wien Heldenplatz. Mythen und Massen. 1848 bis 1998. Verlag Mandelbaum, Wien 2000, S. 13-22 Herbert Haupt Der Heldenplatz Ein Stück europäischer Geschichte im Herzen von Wien Was Wien für die Monarchie ist, das ist die Hofburg für Wien: Der eigentliche Mittelpunkt der Stadt« Richard von Eitelberger, 1859 Zunächst mußte Raum geschaffen werden, damit überhaupt ein Platz entstehen konnte. Am Beginn der Geschichte des Heldenplatzes steht die Sprengung der Burgbastei durch die abziehenden französischen Truppen im Dezember des Jahres 1809. Napoleon hatte mit der Eroberung Wiens (13. Mai 1809) und dem Frieden von Schönbrunn (14. Oktober 1809) den Höhepunkt seiner Macht erreicht. Es war ein blutiger, hart umkämpfter Sieg gewesen, der am Nimbus der Unbesiegbarkeit des Kaisers der Franzosen erste Flecken hinterließ. In der Schlacht bei Aspern und Eßling hatte sich Napoleon zum erstenmal einer einzelnen Macht geschlagen geben müssen. Erzherzog Carl (1771–1847) sollte 50 Jahre später am äußeren Burgplatz ein Denkmal zur Erinnerung an den Sieg errichtet werden. Als bleibende Erinnerung an seine halbjährige Regentschaft in Wien ließ Napoleon vor seinem Abzug die zum Schutze der Hofburg errichtete Bastei sprengen. Doch was als demütigendes Zeichen gedacht war, nahm in Wirklichkeit nur eine Arbeit vorweg, die Kaiser Franz I. (1768–1835) von Österreich früher oder später selbst vorzunehmen gezwungen gewesen wäre. Die neue Waffentechnik verlangte nach einem neuen Befestigungssystem. Die Zeit für Bastionen war abgelaufen. Mit dem Abtragen des Schutts und mit der Beseitigung der an der Außenseite der Basteimauer gelegenen Wachthäuser ließ man sich Zeit. Erst 1816 wurde mit der Planierung des den größeren Teil des heutigen Heldenplatzes umfassenden Areals der Burgbastei begonnen. -

Vienna Guide

April 22—24, 2015, Vienna, Austria Hotel Park Royal Palace Vienna Guide SIGHTSEEING Vienna is old, Vienna is new… and the sights are so varied: from the magnificent Baroque buildings to “golden” Art Nouveau to the latest architecture. And over 100 museums beckon… ALBERTINA The Albertina has the largest and most valuable graphical collection in the world, including works such as Dürer’s “Hare” and Klimt‘s studies of women. Its latest exhibition presents masterpieces of the Modern era, spanning from Monet to Picasso and Baselitz. As the largest Hapsburg residential palace, the Albertina dominates the southern tip of the Imperial Palace on one of the last remaining fortress walls in Vienna. ANKER CLOCK This clock (built 1911–14) was created by the painter and sculptor Franz von Matsch and is a typical Art Nouveau design. It forms a bridge between the two parts of the Anker Insurance Company building. In the course of 12 hours, 12 historical figures (or pairs of figures) move across the bridge. Every day at noon, the figures parade, each accompanied by music from its era. AUGARTEN PORCELAIN MANUFacTORY Founded in 1718, the Vienna Porcelain Manufactory is the second-oldest in Europe. Now as then, porcelain continues to be made and painted by hand. Each piece is thus unique. A tour of the manufactory in the former imperial pleasure palace at Augarten gives visitors an idea of how much love for detail goes into the making of each individual piece. The designs of Augarten have been created in cooperation with notable artists since the manufactory was established. -

Price List Hofburg New Year's Eve Ball on 31 December 2019

PRICE LIST HOFBURG NEW YEAR’S EVE BALL ON 31 DECEMBER 2019 GRAND TICKET WITH GALA DINNER Admission entrance Heldenplatz at 6.30 pm The ticket price includes the entrance and a seat reservation at a table as well as a glass of sparkling wine for the welcome (at the Hofburg Foyer until 7.00 pm), a four-course dinner with white / red wine, mineral water and a glass of champagne at midnight at your table. Musical entertainment by live-orchestras and dance floor. Festsaal EUR 780.- per person Zeremoniensaal Center EUR 730.- per person Zeremoniensaal Wing EUR 700.- per person Geheime Ratstube EUR 520.- per person STAR TICKET WITH SEAT RESERVATION Admission entrance Heldenplatz at 9.15 pm The ticket price includes the entrance ticket and the seat reservation at a table, a glass of sparkling wine for the welcome (at the Hofburg Foyer until 10.00 pm). Festsaal Seat reservation in a centrally located state hall musical entertainment by live-orchestras, dance floor EUR 440.- per person Wintergarten or Marmorsaal Seat reservation in a centrally located state hall or in a room with a view over the Heldenplatz EUR 350.- per person Seitengalerie or Vorsaal seat reservation in a centrally located state hall EUR 300.- per person Künstlerzimmer or Radetzky Appartment seat reservation in a smaller, historical state hall EUR 250.- per person CIRCLE TICKET Admission entrance Heldenplatz at 9.15 pm The ticket price comprises access to all ballrooms and a glass of sparkling wine for the welcome (at the Hofburg Foyer until 10.00 pm). A seat reservation is not included. -

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist a Dissertation Submitted In

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair Professor Jason Wittenberg Professor Jacob Citrin Professor Katerina Linos Spring 2015 The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe Copyright 2015 by Kimberly Ann Twist Abstract The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair As long as far-right parties { known chiefly for their vehement opposition to immigration { have competed in contemporary Western Europe, scholars and observers have been concerned about these parties' implications for liberal democracy. Many originally believed that far- right parties would fade away due to a lack of voter support and their isolation by mainstream parties. Since 1994, however, far-right parties have been included in 17 governing coalitions across Western Europe. What explains the switch from exclusion to inclusion in Europe, and what drives mainstream-right parties' decisions to include or exclude the far right from coalitions today? My argument is centered on the cost of far-right exclusion, in terms of both office and policy goals for the mainstream right. I argue, first, that the major mainstream parties of Western Europe initially maintained the exclusion of the far right because it was relatively costless: They could govern and achieve policy goals without the far right. -

Resume Leonie Hodkevitch

Resume Leonie Hodkevitch Leonie Hodkevitch Author | University Docent | Cultural Producer Austria -1160 Vienna, Herbststrasse 31/18 - 20 Greece-Thessaloniki 54635, Filippou Dragoumi 15 f: A +43.660.4670.007 | GR +30.690.7589.679 e: [email protected] i: www.4p116.com www.21july.net www.c-f.at Education | Master’s degrees Magister Philosophiae summa et magna cum laude, in Spanish Philology, in French Philology, and in Cultural and Social Anthropology, University of Vienna, 1985-1989 University Docent | Lecturer for Cultural Management, Intercultural Communication, Marketing and Sponsoring, Audience Development, European Projects and Social justice through Arts and Culture, since 2001 University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, USA Goethe Institut in Germany, Bulgaria, Greece George Mason University, Washington DC, USA University of Arts, Belgrade, Serbia Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre, Tallinn, Estonia Winthrop University, South Carolina, USA University for Applied Art in Vienna, Austria European Union, Cultural Contact Point New York University, NYU Steinhardt, NYC, USA Croatian Federal Ministry of Culture Austrian Cultural Forums in Tallinn, Lemberg, Belgrade, London, NYC, Washington DC Institute for Cultural Concepts, Vienna, Austria, 2004 - 2014 Leuphana University, MOOC, Germany University of Music and Performing Arts Graz, Austria University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, Austria Cultural Department of Bolzano, Italy Western New England University, Springfield, -

The Future of Western Balkans

news REGION MAGAZINE OF THE INSTITUTE OF THE REGIONS OF EUROPE • 51 / DECEMBER 2018 Austrian‘s young people are very much interested in Save the date: 8th IRE-Expert Conference The future of Western ”Smart Regions“ 20 February 2019 Cultural Center Hallwang/ Balkans Salzburg, Austria 4 CoR-Working Group 6 Conference of the 7 Elections: Western Balkans: Austrian Presidency: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Territorial reform in Albania “Subsidiarity as a construction Hesse, South Tyrol, Poland principle of the European Union“ and Andalusia FOCUS 14th Conference of European Regions and Cities Oberösterreich. Land der Möglichkeiten. Manfred Weber Leading candidate of the EPP for the office of the EU Commission President 2019 Phoenix © MEHR WIRTSCHAFT. MEHR MÖGLICHKEITEN. Let us keep regions in the heart of Europe OÖ auf Innovationskurs When we talk about Europe, we talk a lot about identity. Re- economically advanced regions in Europe are on the national gions are the places where we take our first steps in the world, borders. Many regions like Rhône-Alps region, Lombardi, Lower where we grow up, where we define and shape our personali- Silesia, or my home region Bavaria, have only a real chance to Zukunftstechnologien, innovative Produkte und ties. Our identities are not simply based on national thinking develop thanks to Europe. and culture. European identity is much more than that. The Eu- Fourth, Europe means to live in safe regions. How else could in- Dienstleistungen sowie qualifizierte Fachkräfte sind ropean identity begins in our schools, during a chat at the usual dividual regions deal with the threats of terrorism or the exter- bar, passing the street in our hometown.