Impacts on Democratic Institutions and Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China at the Gates a New Power Audit of Eu-China Relations

CHINA AT THE GATES A NEW POWER AUDIT OF EU-CHINA RELATIONS François Godement & Abigaël Vasselier ABOUT ECFR The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) is the first pan-European think-tank. Launched in October 2007, its objective is to conduct research and promote informed debate across Europe on the development of coherent, effective and values- based European foreign policy. ECFR has developed a strategy with three distinctive elements that define its activities: • A pan-European Council. ECFR has brought together a distinguished Council of over two hundred Members - politicians, decision makers, thinkers and business people from the EU’s member states and candidate countries - which meets once a year as a full body. Through geographical and thematic task forces, members provide ECFR staff with advice and feedback on policy ideas and help with ECFR’s activities within their own countries. The Council is chaired by Carl Bildt, Emma Bonino and Mabel van Oranje. • A physical presence in the main EU member states. ECFR, uniquely among European think-tanks, has offices in Berlin, London, Madrid, Paris, Rome, Sofia and Warsaw. Our offices are platforms for research, debate, advocacy and communications. • Developing contagious ideas that get people talking. ECFR has brought together a team of distinguished researchers and practitioners from all over Europe to carry out innovative research and policy development projects with a pan-European focus. ECFR produces original research; publishes policy reports; hosts private meetings, public debates, and “friends of ECFR” gatherings in EU capitals; and reaches out to strategic media outlets. ECFR is a registered charity funded by the Open Society Foundations and other generous foundations, individuals and corporate entities. -

Relations Between Chambers in Bicameral Parliaments 121

Relations between Chambers in Bicameral Parliaments 121 III. Relations between Chambers in Bicameral Parliaments 1. Introductory Note by the House of Commons of Canada, June 1991 In any bicameral parliament the two Houses share in the making of legisla- tion, and by virtue both of being constituent parts of the same entity and of this shared function have a common bond or link. The strength or weakness of this link is initially forged by the law regulating the composition, powers and functions of each Chamber, but is tempered by the traditions, practices, the prevailing political, social and economic climate and, indeed, even the personalities which comprise the two Chambers. Given all of these variables and all of the possible mutations and combina- tions of bicameral parliaments in general, no single source could presume to deal comprehensively with the whole subject of relations between the Houses in bicameral parliaments. Instead, the aim of the present notes is to attempt to describe some of the prominent features of relations between the two Houses of the Canadian Parliament with a view to providing a focus for discussion. The Canadian Context The Constitution of Canada provided in clear terms: "There shall be One Parliament for Canada, consisting of the Queen, an Upper House styled the Senate, and the House of Commons." The Senate, which was originally designed to protect the various regional, provincial and minority interests in our federal state and to afford a sober second look at legislation, is an appointed body with membership based on equal regional representation. Normally the Senate is composed of 104 seats which are allotted as follows: 24 each in Ontario, Quebec, the western provinces (6 each for Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia) and the Maritimes (10 each in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick and 4 in Prince Edward Island); six in Newfoundland and one each in the Yukon and Northwest Territories. -

Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Gospodarki Krajowej W Kutnie

Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie NR 14 GRUDZIEŃ 2020 PÓŁROCZNIK ISSN 2353-8392 KUTNO 2020 Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie Wydział Studiów Europejskich Rada Programowo-Naukowa Przewodniczący Rady: prof. dr hab. Anatoliy Romanyuk, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie Zastępca Przewodniczącego: dr hab. Zbigniew Białobłocki, Wyższa Szkoła Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie Członkowie: prof. dr hab. Wiera Burdiak, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. Jurija Fedkowycza w Czerniowcach prof. dr hab. Walerij Bebyk, Narodowy Uniwersytet Kijowski im. Tarasa Szewczenki prof. dr hab. Markijan Malski, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie prof. zw. dr hab. Lucjan Ciamaga, Wyższa Szkoła Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie dr hab. Krzysztof Hajder, Uniwersytet im. A. Mickiewicza w Poznaniu prof. dr hab. Walenty Baluk, Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie prof. nadzw. dr Vitaliy Lytvin, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie prof. Pavel Pavlov, PhD, Prorektor ds Badań i Nauki Wolnego Uniwersytetu Warneńskiego prof. Galya Gercheva D.Sc, Rektor Wolnego Uniwersytetu Warneńskiego, ks. dr hab. Kazimierz Pierzchała, Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski Jana Pawła II Recenzenci zewnętrzni: prof. dr hab. Nataliya Antonyuk, Uniwersytet Opolski prof. dr hab. Walerij Denisenko Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie prof. zw. dr hab. Bogdan Koszel, Uniwersytet im. A. Mickiewicza w Poznaniu prof. dr hab. Janusz Soboń, Akademia im. Jakuba z Paradyża w Gorzowie Wielkopolskim prof. dr hab. Wasyl Klimonczuk, Narodowy Uniwersytet Przykarpacki im. Wasyla Stefanyka w Iwano Frankowsku prof. dr hab. Swietłana Naumkina, Narodowy Juznoukrainski Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny im. K. D. Uszynskiego w Odessie prof. dr hab. Galina Zelenjno, Instytut Etnopolitologii im. I. Kurasa w Kijowie dr hab. Krystyna Leszczyńska- Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie Redaktor naczelny: dr hab. -

POLAND Date of Elections: March 21, 1976 Purpose of Elections

POLAND Date of Elections: March 21, 1976 Purpose of Elections Elections were held for all the members of Parliament on the normal expiry of their term of office. Characteristics of Parliament The unicameral Parliament of Poland, the Sejm (Diet), is composed of 460 members elected for 4 years. Electoral System All Polish citizens are entitled to vote provided they are at least 18 years old, have not been convicted of crime or deprived of their civil rights by judgement of a court and are not mentally deficient. Also entitled are persons who have resided in Poland for five years and have no other nationality, even if their Polish citizenship is not yet established. Electoral registers are drawn up at the constituency level by the local people's councils and revised before each election. Voting is not compulsory. Any qualified elector who is at least 21 years of age may stand for election to the Diet. The mandate of deputy is not incompatible with any other public or private function. According to the Constitution amended in 1976, candidates are nominated by political and social organizations embracing the country's urban and rural population. For the 1976 general elections, Poland was divided into 71 constituencies, each returning from three to ten deputies, depending on the constituency's population. Deputies are elected by absolute majority system, with electors in each constituency voting for lists of candidates presented by political parties. Each elector votes for as many candidates as there are seats to be filled in the constituency and, since the names on any party list can exceed this total, may cast preferential votes for candidates of his choice by crossing out names of others. -

Effects of Institutional Variables on Legislative Voting Behaviour: Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Eight Bicameral Legislatures

MASARYK UNIVERSITY The Faculty of Social Studies The Department of Political Science Mgr. Kamil Gregor Effects of Institutional Variables on Legislative Voting Behaviour: Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Eight Bicameral Legislatures Dissertation Thesis Advisor: Prof. PhDr. Maxmilián Strmiska, Ph.D. Brno 2015 1 Affidavit / Čestné prohlášení I declare that this thesis was written by me alone and using only sources listed in References. Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto dizertační práce vypracoval samostatně a pouze s použitím uvedených zdrojů. Brno, 20. 11. 2015 Mgr. Kamil Gregor 2 Abstract This thesis challenges conventional straightforward accounts of legislative voting behaviour found in existing literature by systematically testing a set of hypotheses regarding effects of three institutional independent variables – the dependency of the executive on the legislature, party leadership control over prospects of legislators’ re-election and cameral symmetry – on two dependent variables describing legislative voting behaviour – party group unity and prevalence of strategic legislative voting. In order to control for effects of possible intervening variables, a quasi-experimental design is employed: Values of the three independent variables are dichotomized and eight national bicameral legislatures with all possible combinations of these values are analysed. Differences in values of the dependent variables between the lower and the upper chamber in each legislature are measured. The differences are then used as the outcome in the csQCA method in order to estimate combinations of institutional conditions necessary and sufficient for the measured differences to occur. The thesis finds that in symmetrical legislatures, strategic legislative voting is similarly prevalent in both chambers while in asymmetrical legislatures, it is more prevalent in the lower chamber. -

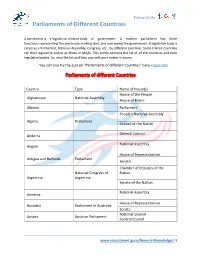

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly -

Kapitalo Valstybinis Reguliavimas, Įgyvendinant Viešojo Ir Privataus Sektorių Partnerystę Torių Partnerystę

www.mruni.eu Živilė Š utavi č IENĖ Živilė ŠutAvičienė DAKTARO DISERTACIJA VIE ĮgyVENDINANT REGULIAVIMAS, VALSTYBINIS KAPITALO Š OJO IR PRIVATAUS SE PRIVATAUS IR OJO Kapitalo valstybinis reguliavimas, įgyvendinant viešojo ir privataus sektorių partnerystę K Torių PARTNERYstę Torių ISBN 978-9955-19-571-9 2013 SOCIALINIAI MOKSLAI, TEISĖ (01 S) VILNIUS, 2013 MYKOLO ROMERIO UNIVERSITETAS Živilė Šutavičienė KAPITALO VALSTYBINIS REGULIAVIMAS, ĮGYVENDINANT VIEŠOJO IR PRIVATAUS SEKTORIŲ PARTNERYSTĘ Daktaro disertacija Socialiniai mokslai, teisė (01 S) Vilnius, 2013 Disertacija rengta 2006–2013 metais Mykolo Romerio universitete Mokslinis vadovas: Prof. dr. Birutė Pranevičienė (Mykolo Romerio universitetas, socialiniai mokslai, teisė – 01 S) nuo 2012 m. spalio 4 d. iki 2013 m. dr. Vytautas Šulija (Mykolo Romerio universitetas, socialiniai mokslai, teisė – 01 S) nuo 2006 m. rugsėjo 1 d. iki 2012 m. spalio 4 d. Konsultantas: Prof. dr. Algimantas Urmonas (Mykolo Romerio universitetas, socialiniai mokslai, teisė – 01 S) nuo 2006 m. iki 2013 m. ISBN 978-9955-19-571-9 Mykolo Romerio universitetas, 2013 TURINYS ĮVADAS ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 I. METODOLOGINIAI VIEŠOJO IR PRIVATAUS KAPITALO SAMPRATOS NAGRINĖJIMO KLAUSIMAI TEISĖJE IR JŲ REIKŠMĖ VALSTYBINIO REGULIAVIMO TOBULINIMUI ADMINISTRACINĖS TEISĖS POŽIŪRIU ..............................................................19 1.1. Metodologiniai kapitalo sąvokos vartojimo galimybių -

Parliament and Democracy

ang_couv.qxd:Mise en page 1 29.1.2008 10:56 Page 1 PARLIAMENT AND DEMOCRACY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY a guide to good practice PARLIAMENT AND DEMOCRACY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY ISBN 978-92-9142-366-8 90000 9 789291 423668 ISBN 978-92-9142-366-8 2006 INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION 2006 •Anglais.qxd:Mise en page 1 3.12.2007 10:44 Page i Un Parlement qui rend des comptes I i PARLIAMENT AND DEMOCRACY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY A GUIDE TO GOOD PRACTICE •Anglais.qxd:Mise en page 1 3.12.2007 10:44 Page ii ii I PARLEMENTS ET DÉMOCRATIE AU 21ÈME SIÈCLE •Anglais.qxd:Mise en page 1 3.12.2007 10:44 Page iii Un Parlement qui rend des comptes I iii PARLIAMENT AND DEMOCRACY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY A GUIDE TO GOOD PRACTICE Written and edited by David Beetham Inter-Parliamentary Union 2006 •Anglais.qxd:Mise en page 1 3.12.2007 10:44 Page iv iv I PARLIAMENT AND DEMOCRACY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY Copyright © Inter-Parliamentary Union 2006 All rights reserved Printed in Switzerland First reprint October 2007 ISBN: 978-92-9142-366-8 No part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, via photo- copying, recording, or otherwise – without the prior permission of the Inter- Parliamentary Union. This publication is circulated subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. -

Allan Rosenbaum

ALLAN ROSENBAUM HOME OFFICE 5000 Riviera Drive Florida International University Coral Gables, Florida 33146 University Park Campus PC 250A (305) 665-1409 Miami, Florida 33199 Phone: (305) 348-1271 [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: Ph.D. Political Science - State and Urban Government American Politics and Public Policy (1976) University of Chicago; Chicago, Illinois M.A. Political Science - Public Administration and Political Psychology (1967) University of California; Berkeley, California M.S. Ed. Administration of Higher Education College Student Personnel (1964) Southern Illinois University: Carbondale, Illinois B.A. History (1962) University of Miami; Miami, Florida PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: June 1994 - Present Professor, Public Administration Director, Institute for Public Management and Community Service and Center for Democracy and Good Governance Florida International University (FIU); Miami, Florida Actively involved in all aspects of Master’s and PhD programs in Public Administration. Led PhD program as it expanded from a dozen to 40 students and achieved considerable international recognition. Also, led NASPAA reaccreditation efforts and state mandated ten-year program reviews of BPA, MPA and PhD programs. Organized videoconference course on contemporary public issues for US Embassy, Warsaw, Poland for Polish international relations students. Represented department in discussions regarding establishing joint BPA and MPA programs in China in conjunction with two Chinese institutions and in discussions regarding establishing joint research and training initiatives with various European and Latin American institutions. Past chair of college tenure and promotion and past chair faculty governance committee. Active involvement in revisions of BPA, MPA and PhD curriculum. Served as Acting Director and Director for founding of a then new FIU School of Public Administration, 2004-06. -

Official Journal of the European Union C 208/1

Official Journal C 208 of the European Union Volume 64 English edition Information and Notices 1 June 2021 Contents EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2019-2020 SESSION Sittings of 13 and 14 November 2019 The Minutes of this session have been published in OJ C 174, 7.5.2021. TEXTS ADOPTED I Resolutions, recommendations and opinions RESOLUTIONS European Parliament Thursday 14 November 2019 2021/C 208/01 European Parliament resolution of 14 November 2019 on the draft Commission implementing decision renewing the authorisation for the placing on the market of products containing, consisting of or produced from genetically modified cotton LLCotton25 (ACS-GHØØ1-3) pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council (D061870/04 — 2019/2856(RSP)) . 2 2021/C 208/02 European Parliament resolution of 14 November 2019 on the draft Commission implementing decision renewing the authorisation for the placing on the market of products containing, consisting of or produced from genetically modified soybean MON 89788 (MON-89788-1) pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council (D061871/04 — 2019/2857(RSP)) . 7 2021/C 208/03 European Parliament resolution of 14 November 2019 on the draft Commission implementing decision authorising the placing on the market of products containing, consisting of or produced from genetically modified maize MON 89034 × 1507 × NK603 × DAS-40278-9 and sub-combinations MON 89034 × NK603 × DAS-40278-9, 1507 × NK603 × DAS-40278-9 and NK603 × DAS-40278-9 pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council (D062828/04 — 2019/2859(RSP)) . -

Attachment 9

Committee of Senior Representatives (CSR) Eighteenth Meeting Oslo, Norway 14-15 April 2011 Reference CSR 18/5/Info 3 Title Baltic Sea Parliamentary Conference’s Rules of Procedure for the Parliamentary Conference, the Standing Committee, the Enlarged Standing Committee, and the Drafting Committee Submitted by Baltic Sea Parliamentary Conference Summary / Note The guidelines concerning an observer status with to the BSPC are contained in Annex 5. Requested action For reference CSR_18-5-Info_3__BSPC_Rules_of_procedure.doc 1 Baltic Sea Parliamentary Conference (B S P C) Rules of Procedure for the Parliamentary Conference, the Standing Committee, the Enlarged Standing Committee, and the Drafting Committee (approved by the 8th Parliamentary Conference on 8thSeptember 1999 in Mariehamn; amended at the 11th Conference in St Petersburg on 1st October 2002; amended by the 14th Parliamentary Conference in Vilnius on 30th August 2005, valid after the 14th Conference has been closed; amended by the 16th Parliamentary Conference in Berlin on 28 August 2007, valid after the 16th Conference has been closed; amended by the 18th Parliamentary Conference in Nyborg on 1 September 2009, valid after the 18th Conference has been closed; amended by the 19th Parliamentary Conference in Mariehamn on 31 August 2010, valid after the 19th Conference has been closed) Preamble Objectives of the Baltic Sea Parliamentary Conference (BSPC) The Conference, BSPC, shall 1) initiate and guide political activities in the region 2) support and strengthen democratic institutions in the participating states 3) improve dialogue between governments, parliaments and civil society 4) strengthen the common identity of the Baltic Sea Region by means of close co-operation between national and regional parliaments on the basis of equality 5) initiate and guide political activities in the Baltic Sea Region, endowing them with additional democratic legitimacy and parliamentary authority Part 1 Participants/Members 1. -

Parliaments and the Pandemic (PDF)

Parliaments and the Pandemic Study of Parliament Group January 2021 Preface The Study of Parliament Group (SPG) was formed in 1964. It arose following the publication of Bernard Crick’s seminal book, 'The Reform of Parliament'. A senior clerk in the House of Commons, Michael Ryle, impressed by the work, but feeling that the author may have benefited from more informed knowledge of the actual operation of parliament, contacted Crick. Both felt that meetings between academics and clerks may be of mutual benefit and, with Sir Edward Fellowes, former Clerk of the House of Commons, they sent a memorandum to various parliamentary officers and academics with an interest in parliament. A meeting was organised in October 1964 at which it was agreed to form a body to promote understanding of the way parliament worked and how it may be more effective. The Study of Parliament Group was born. Since its formation, the Group has held conferences and seminars, formed various working groups and been responsible for publishing books and articles. Submissions have also been made to various parliamentary committees, not least those concerned with procedure and reform. The membership has expanded over the years, encompassing clerks from other legislatures in the United Kingdom as well as some with a scholarly interest in parliament without themselves being academics. To encourage frank exchanges of views, MPs and journalists are excluded from membership, though they are regular speakers at Group events. Publications have included substantial volumes such as 'The House of Commons in the Twentieth Century' (1979), 'The New Select Committees' (revised edn.