HOW to GROW BIG PEACHES1 Richard Marini2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrition Facts N *Learn About Fiber on Page 2

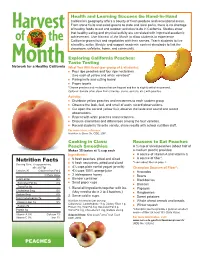

Health and Learning Success Go Hand-In-Hand California’s geography offers a bounty of fresh produce and recreational areas. From stone fruits and salad greens to state and local parks, there is no shortage of healthy foods to eat and outdoor activities to do in California. Studies show that healthy eating and physical activity are correlated with improved academic achievement. Use Harvest of the Month to allow students to experience California-grown fruit and vegetables with their senses. Teach students to live a healthy, active lifestyle and support academic content standards to link the classroom, cafeteria, home, and community. Exploring California Peaches: Taste Testing Network for a Healthy California What You Will Need (per group of 8 students): n Four ripe peaches and four ripe nectarines (two each of yellow and white varieties)* n Paring knife and cutting board n Paper towels *Choose peaches and nectarines that are fragrant and firm to slightly soft when pressed. Optional: Sample other stone fruits (cherries, plums, apricots, etc.) with peaches. Activity: n Distribute yellow peaches and nectarines to each student group. n Observe the look, feel, and smell of each; record observations. n Cut open the second yellow fruit; observe the taste and sound and record observations. n Repeat with white peaches and nectarines. n Discuss similarities and differences among the four varieties. n Record students’ favorite variety; share results with school nutrition staff. For more ideas, reference: Nutrition to Grow On, CDE, 2001. Cooking in Class: Reasons to Eat Peaches Peach Smoothies A ½ cup of sliced peaches (about half of Makes 35 tastes at ¼ cup each a medium peach) provides: Ingredients: n A source of vitamin A and vitamin C. -

Peony, Powdery Mildew (Erysiphe Polygoni)

Problem: Peony, Powdery Mildew (Erysiphe polygoni) Host Plants: Peony Description: Powdery mildew starts as individual spots that resemble snowflakes but rapidly coalesce to cover the entire leaf so that a plant look like it was dusted with flour. Though common on other plants such as lilac and bee balm, it has been relatively rare on peony until the last few years. Recommendations: Poor air movement and shade make the disease more likely. Growing peonies in full sun with good air movement will help minimize the disease. Fungicides can be effective if applied before infection has occurred. Therefore, heavily infected plants should not be treated as the treatment will be ineffective. Fortunately, the disease should cause no lasting damage to the plant. Remove and discard (or compost) infected plant material at the end of the season. Look for individual spots to appear the following spring and then apply a recommended fungicide before the disease has spread. Suggested fungicides include myclobutanil (Eagle, Spectracide Immunox, Monterey Fungi-Maxx, Fertilome F- Stop Lawn & Garden Fungicide), propiconazole (Banner MAXX, Fertilome Liquid Systemic Fungicide, Bonide Infuse Systemic Disease Control) or tebuconazole (BioAdvanced Disease Control for Roses, Flowers & Shrubs). References: 1. Powdery Mildew in the Flower Garden, University of Minnesota Extension 2. Peony Powdery Mildew, University of Illinois Extension, Home, Yard & Garden Pest Newsletter, July 16, 2010 Last Update: 1/16/2020 Brand names appearing in this publication are for product identification purposes only. No endorsement is intended, nor is criticism implied of similar products not mentioned. Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service . -

Peach Volatile Emission and Attractiveness of Different Host Plant

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Peach volatile emission and attractiveness of diferent host plant volatiles blends to Cydia molesta in adjacent peach and pear orchards Peng‑fei Lu1* & Hai‑li Qiao2 The oriental fruit moth (OFM), Cydia (= Grapholitha) molesta, is a highly damaging pest; peaches are its primary host, and pears serve as post‑peach secondary hosts during the late season in China. We collected volatiles from detached peach shoots and fruits, and identifed them with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Antennally active compounds were identifed by gas chromatography-electroantennogram detection (GC-EAD), and these were further tested in the laboratory and feld. We detected consistent electroantennographic activity was for ten compounds. Signifcantly more C. molesta females were caught with a mixture of female EAD-active compounds identifed from the detached matured peach fruits (nonanal, butyl acetate, 3-methylbutyl acetate, hexyl acetate, (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate, linalool and farnesene) than other mixtures mimicking the volatile profle from detached matured fruits or shoots. We identifed a new GC-EAD active mixture from intact peach shoots composed of nonanal, (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate, (E)-β-ocimene, and 6-methyl- 5-hepten-2-one. In the feld test, the background odour of orchards could afect trap catches, and two peach-derived blends together with two previously known pear-derived blends were proven to be able to monitor the seasonal OFM population dispersal in adjacent orchards. These host plant blends will be efective for further designing candidate attractants for season-long C. molesta population dynamic monitoring. Phytochemicals are important olfactory cues for moths to fnd hosts and lay eggs 1–4. -

French Toast Crunch Kale + Bacon Hash Brown Casserole

SEASON 2 | EPISODE 01 and slowly stir, until sugar dissolves, sheet pan with a cooling rack on top of French Toast using a wooden spoon or heat resistant it. This will keep the toast from getting spatula. You’re looking for the mixture soggy while you cook the rest of your Crunch to become an amber color. slices. Repeat until all bread is cooked. prep: 1 hour cook: 10 minutes 4. Immediately take the mixture off the 4. Diagonally cut each slice of french cool: 10 minutes heat and stir in your butter, once butter toast, so that it makes 2 halves out of 1 melts, slowly stir in the heavy cream slice of bread. and salt. caramel crunch 5. Place 5 halves of french toast on a 4 cups corn flakes 5. Grease a sheet pan and set aside. plate and sprinkle with caramel crunch 3/4 cup sugar that was set aside and powdered sugar. 6. Add corn flakes into a large mixing 1/8 teaspoon cream of tartar bowl. Gently stir in the caramel sauce Top with syrup, sliced strawberries, 2 tablespoons water and cinnamon. Toss until cornflakes and a dollop of whipped cream. Serve 3 tablespoons butter, unsalted are coated, and spread into a single immediately. 1/4 cup heavy cream layer on a greased sheet pan. Allow this Makes 6-8 servings Pinch of salt to cool for about an hour 11/2 teaspoon cinnamon 7. Set a small amount of your crunchy mixture to the side for garnish, about 2 french toast cups. Take the remaining mixture and Kale + Bacon 12 slices of Brioche put into a plastic bag, leaving a small gap for air so as to not break the bag. -

Peach Fruit Fly, Bactrocera Zonata, Host List the Berries, Fruit, Nuts and Vegetables of the Listed Plant Species Are Now Considered Host Articles for B

June 2017 Peach fruit fly, Bactrocera zonata, Host List The berries, fruit, nuts and vegetables of the listed plant species are now considered host articles for B. zonata. Unless proven otherwise, all cultivars, varieties, and hybrids of the plant species listed herein are considered suitable hosts of B. zonata. Scientific Name Common Name Aegle marmelos (L.) Correa Baeltree Afzelia xylocarpa (Kurz) Craib Doussie Annona reticulata L. Custard apple Annona squamosa L. Sugar apple Careya arborea Roxb. Patana oak Carica papaya L. Papaya Casimiroa edulis La Llave & Lex. White sapote Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai Watermelon Citrus aurantium L. Sour orange Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f. Lemon Citrus nobilis x Citrus deliciosa Ten. Kinnow Citrus paradisi Macfad. Grapefruit Citrus reticulata Blanco Mandarin orange Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck Orange Coccinia grandis (L.) Voigt Ivy gourd Cucumis sativus L. Cucumber Cydonia oblonga Mill. Quince Elaeocarpus hygrophilus Kurz Ma-kok-nam Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl. Loquat Ficus carica L. Fig Grewia asiatica L. Phalsa Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. Bottle gourd Luffa acutangula (L.) Roxb. Angled loofah Luffa spp. Tori Malpighia emarginata DC. Barbados cherry Malus pumila Mill. Apple Malus sylvestris (L.) Mill. Crab apple Mangifera indica L. Mango Manilkara zapota (L.) P. Royen Sapodilla Mimusops elengi L. Spanish cherry Momordica charantia L. Bitter melon Olea europaea L. Olive Persea americana Mill. Avocado Phoenix dactylifera L. Date palm Prunus armeniaca L. Apricot Prunus avium (L.) L. Sweet cherry Prunus domestica L. Plum Prunus persica (L.) Batsch Peach Prunus sp. N/A Psidium cattleyanum Sabine Strawberry guava Psidium guajava L. Guava Punica granatum L. Pomegranate Putranjiva roxburghii Wall. -

Comparative Analysis of Nodulation-Related Small Secreted Peptides Across Legume Species

Comparative analysis of nodulation-related small secreted peptides across legume species A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Diana Trujillo IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Nevin Young November 2017 © Diana Trujillo 2017 Acknowledgments I would like to thank all those who, one way or another, have made this work possible. First and foremost, thanks go to my advisor, Nevin Young, who helped shape my vision for this project and was always available to give me support or the necessary guidance in the right direction. I would also like to thank Kevin Silverstein who played a large role during the development of my LSE pipeline, and was a helpful mentor in bioinformatic matters. Thanks to the other members of my advisory committee, Peter Morrell, Michael Sadowsky, and Robert Stupar, who provided a fresh outlook and valuable advice that helped to improve this study. I would like to thank Joseph Guhlin and Peng Zhou who were always one step away when I had Unix concerns, and Shaun Curtin and Roxanne Denny who guided me through the technical aspects of growing or transforming Medicago. I am grateful that I had a strong network of friends and colleagues to discuss biology, coding, and life. To Allison Haaning, Beth Fallon, Christina Smith, Leland Werden, Derek Nedveck, and Eli Krumholz: thanks for sharing the journey. I would like to thank my mother, María Cecilia, who instilled my love of reading, truth-seeking, and plants. To my husband, Dylan Huss, thank you for always calling to see if I already ate (including as I typed these words). -

Tolerance of Apple and Peach Trees to Triclopyr

HORTSCIENCE 28(10):1021-1023. 1993. mine the extent of apple and peach tree toler- ance to triclopyr. Fruit trees have shown toler- ance to triclopyr, a postemergence herbicide Tolerance of Apple and Peach Trees to that controls important orchard broadleaf weeds, such as Virginia creeper (Young, 1989). Triclopyr Triclopyr at 0.1 to 1.12 kg acid equivalent (a.e.)/ha reduced ground cover by this weed in Jeffrey F. Derr peaches (Tworkoski and Young, 1990). Vir- Department of Plant Pathology, Physiology, and Weed Science, Virginia ginia creeper regrew, especially at the lower Polytechnic Institute and State University, Hampton Roads Agriculture triclopyr rates; however, control was accept- able with triclopyr applied at 1.12 kg·ha-1 for Experiment Station, Virginia Beach, VA 23455 two consecutive years. Triclopyr was equally Additional index words. Malus domestica, Prunus persica, crop injury, postemergence effective when applied in July, August, or herbicides, weed control September (Tworkoski and Young, 1989). Virginia creeper rooted near a tree trunk was Abstract. The tolerance of newly planted apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) and peach difficult to control since its foliage was pro- [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] trees to the postemergence herbicide triclopyr was evaluated tected from the herbicide by the tree crown. infield trials. Apple and peach trees were not injured by triclopyr applied at rates ranging The ester formulation of triclopyr was more from 0.28 to 1.12 kg acid equivalent (a.e.)/ha as a directed spray to soil. No injury was effective than the amine formulation for Vir- observed following direct application of 10 ml of a triclopyr solution at 2 g a.e./liter to the ginia creeper control (Tworkoski et al., 1988). -

Peach Basics Types of Peaches E Vitamin C Provid , Whi Freestone — the Pit Falls out Es Ch H Ch Cuts an El Easily

Give Your Family More of the Good Stuff! Peach Basics Types of Peaches e vitamin C provid , whi Freestone — the pit falls out es ch h ch cuts an el easily. These varieties have firm ea y heal d other ps P bod wo ur un texture, low sugar content, low o ds y . juiciness, and white or yellow flesh. White flesh peaches may be slightly less sweet and $ $ lower in acid than yellow flesh hop and ave peaches. < Choose peaches that have an Clingstone — the flesh clings even, creamy gold to yellow to the pit. These varieties have color. Some varieties have a red soft texture, high sugar content blush but it may not always be and juiciness, and white or a sign of ripeness. yellow flesh. < When ripe, peaches should Sem i-freestone — a hybrid of have a slight “give” or softness. freestone and clingstone Handle peaches gently—they peaches. The flesh clings to the bruise easily. Bruised areas pit less tightly spoil more quickly. and they are < Fresh peaches may be at relatively high peak quality and lowest cost in sugar content from June through September, and juiciness. depending on the variety and growing area. < When shopping for canned peaches, look for “Packed in tore Wel I Wash peaches just 100% juice” and “No sugar S l before using by added” on the label. Canned ste Les gently rubbing and frozen peaches are Wa s under running water. I available year-round. Keep peaches at room temperature I To keep them from browning, until ripe for best flavor and texture. -

Crop Profile for Peaches in Georgia and South Carolina

Crop Profile for Peaches in Georgia and South Carolina Prepared: March, 2004 General Production Information Georgia and South Carolina rank 2nd and 3rd, respectively, in U.S. peach production. Annual production for the combined Georgia and South Carolina peach crops (NASS, 1997–2001) averages 226 million lbs, with an average value of $63 million. Together, Georgia and South Carolina account for 25% of the nation’s fresh peach acreage. The Georgia and South Carolina peach crops are grown almost exclusively for fresh sales. Wholesale grower-shippers, who sell primarily to chain stores, market over 90% of the crop. Both Georgia and South Carolina wholesale grower-shippers view themselves as facets of a single production area, as most use the same brokers and ship to the same markets. Roadside and local sales are next in importance. Processing, primarily for baby food, is limited, accounting for less than 1% of sales. Production Regions Peach production is clustered in areas where quality orchard sites offer some measure of freedom from spring frosts, and soils that support good tree growth and orchard longevity. Middle Georgia’s Fort Valley plateau and South Carolina’s Ridge area are the epicenters of production in the two-state area. Collectively, they account for ca. 70% of the bearing acreage in the two states. Significant production is also found in Georgia’s Brooks County (southwest GA) and in South Carolina’s piedmont region (northwest SC). Smaller areas of production are in west central and southeast Georgia and additional The Crop Profile/PMSP database, including this document, is supported by USDA NIFA. -

A Penny for Your Pensees

North Carolina .<£i^*>, Flower Growers' x Bulletin Volume 40, Number 3 June, 1995 F*G *A Official Publication ofthe North Carolina Commercial Flower Growers' Association A Penny for Your Pensees Douglas A. Bailey, Dept. of Horticultural Science, James R. Baker, Dept. of Entomology, and Ronald K. Jones, Dept. of Plant Pathology North Carolina State University Pansies have become the most popular traced back to the French word pensee, meaning annualfor mid-fall to late-springcolor thought or remembrance. The wild pansy is in the Southeast. Intensive breeding different from other violas in two distinct ways: programs that have selected for unique flower O Wild pansies grow from the ground on one colors, large flower size, greater flower number, main stem then branchabove the ground, whereas and temperature tolerance have led to many new violas branch below the ground on stolons with and exciting cultivars to selectfrom for use in the many plants sharing the same root system; and landscape. Thisarticle was writtento give readers @Wild pansies have blooms that arelarger and an appreciationfor history anddiversityoftoday's more round than viola flowers (Liberty Hyde pansy as well as offer production advice. Bailey Hortorium, 1976). By the early 1600*8, wild pansies were cultivated in Europe by many History gardeners. The modern pansy, Viola X wittrockiana, is The origin of the plant we now call pansy thought to have derived from Viola tricolor, a began in England (National Garden Bureau, native ofcentral Europe. Although pansies are a 1993). Between 1814 and 1839, Lord Bambier perennial in cooler climates, they are grown as a and his gardener William Thompson began cool season annual in the Southeast and rarely crossing various Viola species in the southern survive our summer heat. -

Fruit-Trees-Means-Nursery-2017.Pdf

BOT_NAME COM_NAME TYPE FEATURES Developed by the University of Minnesota in 1991, a cross of Macoun and Honeygold. Crisp, juicy, sweet apple ranked as one of the highest quality apples. Over 3" Apple is richly coral-colored with a Malus Dwf Honey Crisp Apple Honey Crisp Apple Dwarf Tree/Fruit Apple yellow background. Stores Well. Pollenizer reccomended. Vigorous, compact, spreading tree. Large waxy fruits ripen in late fall. Crisp, juicy white flesh has a long-lasting sweet, snappy flavor. Excellent for cooking with a good shelf life. Self-fertile. Malus 'Granny Smith' S.D. Apple Semi-Dwf. Granny Smith Tree/Fruit Apple Deciduous. Developed in 1953 in New York, a cross between the crisp Golden Delicious and the blush-crimson Jonathan. They form a large sweet fruit with a thin skin. Jonagold is triploid, with sterile pollen, and Malus Jonagold Apple SD Jonagold Apple Semi Dwf Apple Tree/Fruit Apple as such, requires a second type of apple for pollen and is incapable of pollenizing other cultivars Known simply as King, the large yellow-green apples with red stripes are excellent for eating fresh, for Malus 'King' S.D. Apple Semi-Dwf. King Tree/Fruit Apple cooking and for making cider. They also keep well. Developed by the University of Minnesota in 1991, a cross of Macoun and Honeygold. Crisp, juicy, sweet apple ranked as one of the highest quality apples. Over 3" Apple is richly coral-colored with a Malus SD Honey Crisp Apple Honey Crisp Apple Semi Dwarf Tree/Fruit Apple yellow background. Stores Well. Pollenizer reccomended. Deciduous fruiting tree produces small pink single flowers in spring which turn white. -

Hosts of Plum Curculio, Conotrachelus Nenuphar (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), in Central Georgia

COMMUNITY AND ECOSYSTEM ECOLOGY Hosts of Plum Curculio, Conotrachelus nenuphar (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), in Central Georgia 1 2 3 3 DAVID JENKINS, TED COTTRELL, DAN HORTON, AMANDA HODGES, AND GREG HODGES USDAÐARS, Southeastern Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, Byron, GA 31008 Environ. Entomol. 35(1): 48Ð55 (2006) ABSTRACT Potential host plants for the larvae of plum curculio, Conotrachelus nenuphar (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), in central GeorgiaÕs peach producing region were surveyed. This fruit-attacking curculionid is reported to have a broad host range, including many plants in the Rosaceae and other families. However, our collections indicated that in this region plum curculio largely is limited to peach (Prunus persica) and plum (P. angustifolia and P. umbellata). Abandoned peach orchards and wild plum thickets are important hosts for the spring generation of plum curculio and are sources of subsequent infestations of managed peach orchards. However, only abandoned peach orchards were available to the summer generation of plum curculio. May haw, Crataegus aestivalis, was also a host, but other species of Crataegus were not used. Although the plum curculio was reported to be a signiÞcant pest of blueberries (Vaccinium spp.) in North Carolina, New Jersey, and Delaware, they were only rarely used as a host in central Georgia. Apple (Malus domestica) and Asian pear (Pyrus pyrifolia), when available, were ovipositional hosts of plum curculio in central Georgia; however, no larvae emerged from these hosts. We report the Þrst records of plum curculio developing in Vaccinium stamineum and Vitis rotundifolia. Our results are compared with a previous survey conducted in the northeastern United States, as well as to data reported in the literature.