Resources Within Reach Iowa’S Statewide Historic Preservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of the State Archaeologist Academic Activities

Office The Year in Review OSA mission statement, academic activities, staff achievements, annual work plan accomplishments, and plans and prospects for of the State FY 2019. By the Numbers Archaeologist 30,094 An overview of FY 2019 through numbers and charts. Fiscal Year 2019 Student Success Eighteen undergraduate and one graduate students were Annual Report involved in various OSA archaeological and related research and repository activities over the course of the fiscal year. Research The OSA conducts a wide range of research activities to discover the archaeological and architectural history of Iowa and surrounding midcontinent over the last 13,000 years. Bioarchaeology In FY 2019 the OSA Bioarchaeology Program’s efforts have focused on fulfilling its responsibilities towards the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act as well as engaging in public education and outreach events. Strategic Initiatives The OSA provides resources and opportunities that encourage the understanding, appreciation, and stewardship of Iowa’s archaeological past. OSA Mission The Year in The position of State Archaeologist was established in 1959. Read the entire mission statement Review Advisory Committee Indian Advisory Council Academic Activities OSA staff instructed four UI classes during FY 2019 including CRM Archaeology and Human Osteology. OSA hosted eight Brown Bag lectures and a creative writing class for the UI English Department. Office and Staff Achievements During FY 2019, OSA staff were recognized for their outstanding professional presence and decades of service. We also welcomed three new hires to the OSA team! FY 2019 Annual Work Plan Accomplishments In FY 2019 the OSA continued energetically pursuing research, education and outreach, and service activities throughout Iowa, the surrounding region, and internationally. -

The Archaeology of Two Lakes in Minnesota

BLM LIBRARY 88000247 BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT EASTERN STATES OFFICE THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF TWO LAKES IN MINNESOTA by Christina Harrison CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES NO. 2 Cover drawing by Shelly H. Fischman. Copies of this report may be obtained from the Bureau of Land Management, Eastern States Office, 350 South Pickett Street, Alexandria, Virginia 22304, or National Technical Information Services, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, Virginia 22161, (703)487-4650. BLM/ES/PT-85-001-4331 # w*^ •Ml THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF TWO LAKES IN MINNESOTA By Christina Harrison BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT LIBRARY Denver, Colorado 8866624? Richard Brook General Editor 1985 Management Bureau of Land Center BR Denver Federal Denver, CO 80225 FOREWORD This report combines under one cover the results of archaeological investigations conducted along two Minnesota lakes — Birch Lake Reservoir in the north, along which 21-SL-165 [gator, Ms. Christina Harrison and her assistants. The BLM is very appreciative of the excellent work. The excavation program at SL-165 was part of the BLM compliance requirements for approval for public sale of the parcel on which the site is located. By contrast, the investigation of BE-4A, The settlement picture at BE-44 confirms an existing and more clearly elucidated pattern characteristic of late Archaic-early Woodland occupation in this part of Minnesota. Generally, during this time period, groups ^ *._.._ j ~ J -r„i„_j„ j ___j i i± a. «. _ „i in i_i j .. _ j The contractor has outlined several management recommendations to be considered in reducing or alleviating the erosion problems on BE-44. -

The Naming, Identification, and Protection of Place in the Loess Hills of the Middle Missouri Valley

The Naming, Identification, and Protection of Place in the Loess Hills of the Middle Missouri Valley David T. McDermott B.A., Haverford College, 1979 B.S., State University of New York, 1992 M.A., University of Kansas, 2005 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________________ James R. Shortridge, Ph. D., Chair _________________________________ J. Christopher Brown, Ph. D. _________________________________ Linda Trueb, Ph. D. _________________________________ Terry A. Slocum, Ph. D. _________________________________ William Woods, Ph. D. Date defended: October 22, 2009 The Dissertation Committee for David T. McDermott certifies that this the approved version of the following dissertation: THE NAMING, IDENTIFICATION, AND PROTECTION OF PLACE IN THE LOESS HILLS OF THE MIDDLE MISSOURI VALLEY Committee: _________________________________ James R. Shortridge, Ph. D., Chair _________________________________ J. Christopher Brown, Ph. D. _________________________________ Linda Trueb, Ph. D. _________________________________ Terry A. Slocum, Ph. D. _________________________________ William Woods, Ph. D. Date approved: October 27, 2009 ii It is inconceivable to me that an ethical relation to land can exist without love, respect, and admiration for land, and a high regard for its value. By value, I of course mean something broader than mere economic value; I mean value in the philosophical -

Iowa City, Iowa - Tuesday, June 6, 2006 NEWS

THE INDEPENDENT DAILY NEWSPAPER FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA COMMUNITY SINCE 1868 The Daily Iowan TUESDAY, JUNE 6, 2006 WWW.DAILYIOWAN.COM 50¢ LAVALLEE’S CRÊPES Hoping to govern WHERE TO VOTE CANDIDATES Polls for today’s primary elections will open at 7 a.m. and close at 9 p.m. To be eligible, voters must be affiliated with either the Democratic or Republican Parties or register with either at their polling places, which can be found by accessing http://www.johnson-county.com/audi- tor/lst_precinctPublicEntry.cfm. Voters are eligible to vote only for candidates from their registered party. Today’s winners will repre- sent their respective parties in the Nov. 7 general election. MIKE BLOUIN CHET CULVER ED FALLON Blouin graduated from Culver, the son of Fallon graduated from Dubuque’s Loras College former U.S. Sen. John Drake University with a with a degree in political Culver, graduated from degree in religion in science in 1966. After a Virginia Tech University 1986. He was elected to stint as a teacher in with a B.A. in political the Iowa House of Dubuque, he was elected science in 1988 and a Representatives in to the Iowa Legislature at master’s from Drake in 1992, and he is age 22, followed by two 1994 before teaching currently serving his terms in the U.S. House. high school in Des seventh-consecutive BACKGROUND He later worked in the Moines for four years. term. Fallon is the Carter administration, and Culver was elected executive director and he most recently served Iowa’s secretary of co-founder of 1,000 as the director of the State in 1998; his Friends of Iowa, an Iowa Department of second term will expire organization promoting Economic Development. -

The Iowa Bystander

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1983 The oI wa Bystander: a history of the first 25 years Sally Steves Cotten Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cotten, Sally Steves, "The oI wa Bystander: a history of the first 25 years" (1983). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16720. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16720 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Iowa Bystander: A history of the first 25 years by Sally Steves Cotten A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1983 Copyright © Sally Steves Cotten, 1983 All rights reserved 144841,6 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iii I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE EARLY YEARS 13 III. PULLING OURSELVES UP 49 IV. PREJUDICE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA 93 V. FIGHTING FOR DEMOCRACY 123 VI. CONCLUSION 164 VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 175 VIII. APPENDIX A STORY AND FEATURE ILLUSTRATIONS 180 1894-1899 IX. APPENDIX B ADVERTISING 1894-1899 182 X. APPENDIX C POLITICAL CARTOONS AND LOGOS 1894-1899 184 XI. -

Mid-Term Report Format and Requirements

Final Report Form REAP Conservation Education Program Please submit this completed form electronically as a Word document to Susan Salterberg [email protected] (CEP contract monitor). Project number (example: 12-04): 13-14 Project title: Investigating Shelter, Investigating a Midwestern Wickiup Organization’s name: University of Iowa Office of the State Archaeologist Grant project contact: Amy Pegump Report prepared by: Lynn M. Alex Today’s date: March 17, 2014 Were there changes in the direction of your project (i.e., something different than outlined in your grant proposal)? Yes No If yes, please explain the changes and the reason for them: No major changes in the direction of the project, although an extension was received to complete one final task. Slight change to line item categories on the budget, but approval was received in advance for these. Note: Any major changes must be approved by the Board as soon as possible. Contact CEP Contract Monitor, Susan Salterberg, at [email protected] or 319-337-4816 to determine whether board approval is needed for your changes. When the REAP CEP Board reports to the Legislature on the impact of REAP CEP funds on environmental education in Iowa, what one sentence best portrays your project’s impact? Response limited to 375 characters. Character limits include spaces. This upper elementary curriculum provides authentic, inquiry-based lessons for educators and their students to learn more about Iowa's early environments, natural resources, and the interrelationship with early human residents and lifeways. Please summarize your project below in the space provided. Your honesty and frankness is appreciated, and will help strengthen environmental education in Iowa. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section Number 7 Page 1

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior 3 0 National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form TER Of HISTORIC PLACES IONAL PARK SFRVICF This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Dubuque Young Men's Christian Association Building other names/site number Iowa Inn 2. Location street & number 125 West Ninth Street n/a PI not for publication citv or town Dubuque n/afl vicinity state Iowa code IA county Dubuque code 061 zip code 52001 As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Jf nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property V meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

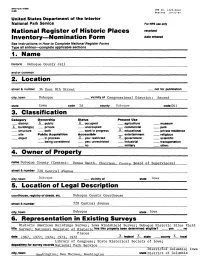

National Register of Historic Places Inventory — Nomination Form Date Entered 1. Name 2. Location 3. Classification 4. Owner O

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places Inventory — Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries — complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Dubuque County Jail ______________ and or common 2. Location street & number 36 East 8th Street not for publication city, town Dubuque vicinity of Congressional District: Second state Iowa code IA county Dubuque code 061 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district X public X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress X educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted X government scientific being considered - yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military __ other: 4. Owner of Property name Dubuque County (Contact: Donna Smith, Chairman, Cmmt-y Board of Supervisors') street & number 720 Central AVenue city, town Dubuque vicinity of state Ibwa 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Dubuque County Courthouse street & number 720 Central Avenue city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Surveys __________ Historic American Buildings Survey; Iowa Windshield Survey; Dubuque Historic Sites Field Survey; National Register of Historic has this property been determined eligible? —— yes —— no Places date 1967, 1977; 1974; 1973. 1972 L federal X_ state __ county X_ local Library of Congress; State Historical Society of Iowa; depository for survey records National Park Service ________ Districtof Columbia; Iowa city, town ; T)p..«=i Mm'TIPS; Waghingtrm state^District of Columbia 7. -

Milebymile.Com Personal Road Trip Guide Iowa United States Highway #52

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide Iowa United States Highway #52 Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 The Savanna-Sabula Bridge The Savanna-Sabula Bridge, a truss bridge and causeway crossing the Mississippi River and connecting the city of Savanna, Illinois with the island city of Sabula, Iowa. The bridge carries United States Highway #52 over the river. This is where the Iowa part of the United States Highway #52 starts its run to terminate at the Iowa/Minnesota Stateline, just south of Prosper, Minnesota. The Savanna-Sabula Bridge is a registered National Historic Place. Altitude: 584 feet 2.7 Sabula, IA Sabula, Iowa, a city in Jackson County, Iowa, It is the Iowa's only island city with a beach and campground. Sabula Public Library, South Sabula Lakes Park, Altitude: 594 feet 3.7 Junction Junction United States Highway #67/State Highway #64, 608th Avenue, Sabula Lake Park, Miles, Iowa, a city in Jackson County, Iowa, Miles Roadside Park, United States Highway #67 passes through Almont, Iowa, Clinton, Iowa, Altitude: 633 feet 6.3 607th Avenue/602nd 607th Avenue, 602nd Avenue, Joe Day Lake, Big Sieber Lake, Altitude: Avenue 686 feet 10.2 Green Island Road Green Island Road, 540th Avenue, Densmore Lake, Upper Mississippi River Wildlife and Fish Refuge, Little Sawmill Lake, Sawmill Lake, located off United State Highway #52, along the Mississippi River in Iowa. Altitude: 823 feet 12.1 500th Avenue: Reeceville, 500th Avenue, County Road Z40, Community of Green Island, Iowa, IA Altitude: 837 feet 14.2 Green Island Road Green Island Road, Community of Green Island, Iowa, Upper Mississippi River Wildlife and Fish Refuge, Altitude: 610 feet 18.7 County Highway 234 County Highway 234, 435th Avenue, Bonnie Lake, Western Pond, located alongside United States Highway #52, part of Upper Mississippi River Wildlife and Fish Refuge. -

Frontier Settlement and Community Building on Western Iowa's Loess Hills

Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 93 Number Article 5 1986 Frontier Settlement and Community Building on Western Iowa's Loess Hills Margaret Atherton Bonney History Resource Service Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1986 Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation Bonney, Margaret Atherton (1986) "Frontier Settlement and Community Building on Western Iowa's Loess Hills," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, 93(3), 86-93. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol93/iss3/5 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bonney: Frontier Settlement and Community Building on Western Iowa's Loes Proc. Iowa Acacl. Sci. 93(3):86-93, 1986 Frontier Settlement and Community Building on Western Iowa's Loess Hills MARGARET ATHERTON BONNEY History Resource Service, 1021 Wylde Green Road, Iowa City, Iowa 52240 Despite the unique Loess Hills topography, Anglo-European settlement in the Loess Hills followed a well established pattern developed over two-hundred years of previous frontier experience. Early explorers and Indian traders first penetrated the wilderness. Then the pressure ofwhite settlement caused the government to make treaties with and remove Indian tribes, thus opening a region for settlement. Settlers arrived and purchased land through a sixty-year-old government procedure and a territorial government provided the necessary legal structure for the occupants. -

The Iowa State Capitol Fire 19041904 Contentse Introduction the Iowa State Capitol Fire: 1904…………………………1

The Iowa State Capitol Fire 19041904 Contentse Introduction The Iowa State Capitol Fire: 1904…………………………1 Section One Executive Council Report…………………...………………..3 Section Two Senate and House Journals…………………………….…...4 Section Three Pictures……………………………………………………...……..6 Section Four Fireproof……………………………………………………...….13 Section Five 1904 Iowa Newspaper Articles………..…………...…...19 Section Six Capitol Commission Report………………………………...68 November 2012 The Iowa State Capitol Fire January 4, 1904 Introduction The Iowa State Capitol Fire: 1904 The Iowa State Capitol Fire: 1904 1 Introduction The Iowa State Capitol Fire: 1904 he twenty-first century Iowa State Capitol contains state-of-the-art fire T protection. Sprinklers and smoke detectors are located in every room and all public hallways are equipped with nearby hydrants. The Des Moines Fire Department is able to fight fires at nearly any height. However, on Monday morning, January 4, 1904, the circumstances were much different. By the beginning of 1904, the Capitol Improvement Commission had been working in the Capitol for about two years. The commissioners were in charge of decorating the public areas of the building, installing the artwork in the public areas, installing a new copper roof, re-gilding the dome, replacing windows, and connecting electrical lines throughout. Electrician H. Frazer had been working that morning in Committee Room Number Five behind the House Chamber, drilling into the walls to run electrical wires and using a candle to light his way. The investigating committee determined that Frazer had left his work area and had neglected to extinguish his candle. The initial fire alarm sounded at approximately 10 a.m. Many citizen volunteers came to help the fire department. -

Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments

Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments by Thomas J. Sloan, Ph.D. Kansas State Representative Contents Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments ....................................... 1 The Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas ..................... ................................................................................................................... 11 Prairie Band of Potawatomi ........................... .................................................................................................................. 15 Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska .............................................................................................................................. 17 Appendix: Constitution and By-Laws of the Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas ..................................... .................. ............................................................................................... 19 iii Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments Overview of American Indian Law cal "trust" relationships. At the time of this writing, and Tribal/Federal Relations tribes from across the United States are engaged in a lawsuit against the Department of the Interior for At its simplest, a tribe is a collective of American In- mismanaging funds held in trust for the tribes. A fed- dians (most historic U.S. documents refer to "Indi- eral court is deciding whether to hold current and