Trans-Zab Jewish Neo-Aramaic1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing Land & Property Issues

HOUSING LAND & PROPERTY ISSUES AMONG IDPs SETTLED IN BASRA, DOHUK, ERBIL & BAGHDAD QUICK ASSESSMENT REPORT – DRAFT 13 November 2014 The purpose of the rapid Housing, Land and Property (HLP) survey, initiated by UN-Habitat among internally displaced people (IDPs) currently living in five key Iraqi cities, is to collect indicative data on land tenure status of the displaced and improving our understanding of issues related to the possible return of IDPs to their former properties. The data collection was undertaken between September and November 2014 by UN-Habitat staff in collaboration with local partners and community representatives, on the basis of a purposely-developed questionnaire. The present report focuses on information captured from 774 IDPs households currently living in Basra, Dohuk, Erbil, Baghdad, respectively the capitals of the Basra, Dohuk, Erbil and Baghdad governorates.1 The surveys were conducted in IDPs camp, planned and unplanned urban areas, hotels and churches. These locations were selected for the presence of large numbers of displaced, accessibility by local partners and took into consideration the geographic and ethnical diversity of respondents. KEY SURVEY FINDINGS Provenance of IDPs : The large majority of the IDPs interviewed for this survey has abandoned properties in the northern Governorate of Ninawa, namely the towns of Al-Hamdaniya, Mosul and Tilkef; followed by the Governorates of Anbar, Diyala, Salah El-den, Kirkuk, Baghdad and Al-Hilla. Figure 1 below provides a breakdown by Governorate. It should be noted that many of those that fled the sectarian clashes affecting the Governorate of Ninawa are Christian minorities, some of which had sought refuge in the Nineveh plains 2 and for whom the present location is therefore not their first displacement. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Operation Inherent Resolve Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress

OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS JANUARY 1, 2021–MARCH 31, 2021 FRONT MATTER ABOUT THIS REPORT A 2013 amendment to the Inspector General Act established the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) framework for oversight of overseas contingency operations and requires that the Lead IG submit quarterly reports to the U.S. Congress on each active operation. The Chair of the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency designated the DoD Inspector General (IG) as the Lead IG for Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR). The DoS IG is the Associate IG for the operation. The USAID IG participates in oversight of the operation. The Offices of Inspector General (OIG) of the DoD, the DoS, and USAID are referred to in this report as the Lead IG agencies. Other partner agencies also contribute to oversight of OIR. The Lead IG agencies collectively carry out the Lead IG statutory responsibilities to: • Develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight of the operation. • Ensure independent and effective oversight of programs and operations of the U.S. Government in support of the operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, investigations, or evaluations. • Report quarterly to Congress and the public on the operation and on activities of the Lead IG agencies. METHODOLOGY To produce this quarterly report, the Lead IG agencies submit requests for information to the DoD, the DoS, USAID, and other Federal agencies about OIR and related programs. The Lead IG agencies also gather data and information from other sources, including official documents, congressional testimony, policy research organizations, press conferences, think tanks, and media reports. -

EASO Rapport D'information Sur Les Pays D'origine Iraq Individus Pris

European Asylum Support Office EASO Rapport d’information sur les pays d’origine Iraq Individus pris pour cible Mars 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Rapport d’information sur les pays d’origine Iraq Individus pris pour cible Mars 2019 D’autres informations sur l’Union européenne sont disponibles sur l’internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-051-5 doi: 10.2847/95098 © European Asylum Support Office 2019 Sauf indication contraire, la reproduction est autorisée, moyennant mention de la source. Pour les contenus reproduits dans la présente publication et appartenant à des tierces parties, se référer aux mentions relatives aux droits d’auteur desdites tierces parties. Photo de couverture: © Joel Carillet, un drapeau iraquien flotte sur le toit de l’église syro- orthodoxe Saint-Ephrem de Mossoul (Iraq), qui a été fortement endommagée, quelques mois après que ce quartier de Mossoul a été repris à l’EIIL. L’emblème de l’EIIL était peint sur la façade du bâtiment durant l’occupation de Mossoul par l’EIIL. EASO RAPPORT D’INFORMATION SUR LES PAYS D’ORIGINE IRAQ: INDIVIDUS PRIS POUR CIBLE — 3 Remerciements Le présent rapport a été rédigé par des experts du centre de recherche et de documentation (Cedoca) du bureau belge du Commissariat général aux réfugiés et aux apatrides. Par ailleurs, les services nationaux d’asile et de migration suivants ont procédé à une relecture du présent rapport, en concertation avec l’EASO: Pays-Bas, Bureau des informations sur les pays et de l’analyse linguistique, ministère de la justice Danemark, service danois de l’immigration La révision apportée par les départements, experts ou organisations susmentionnés contribue à la qualité globale du rapport, mais ne suppose pas nécessairement leur approbation formelle du rapport final, qui relève pleinement de la responsabilité de l’EASO. -

Rapid Market Assessment Report Hamadanyia District, Ninewa Islamic Relief Worldwide, Iraq December 2019

Rapid Market Assessment Report Hamadanyia District, Ninewa Islamic Relief Worldwide, Iraq December1 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Al-Mosul Center for Culture and Sciences (MCCS) thanks Islamic Relief Iraq team for their cooperation and support with this rapid market assessment in Sinjar and Al-Hamdaniya , Ninewa Iraq. In particular, we would like to recognize: Akram Sadeq Ali Head of Programmes Noor Khan Mengal Project Manager Hawree Rasheed Project Coordinator Field research would not have been possible without the participation of government representatives, Mosul Chamber of Commerce as well as the assistance of local residents from the project targeted areas who took part in the research as enumerators and participants. The following individuals contributed to the field research and analysis undertaken for this research: Al-Mosul Centre for Culture and Sciences (MCCS) Ibrahim Adeeb Ibrahim Data analyst and report writer Hammam Alchalabi Team Leader Disclaimer: This report was made possible by the financial support of the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Iraq Crisis Response and Resilience Programme (ICRRP) with generous funding from the Government of Japan through Islamic Relief Iraq (Agreement No. P/AM 204/19). This report is not a legally binding document. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and does not reflect the views of any of the contributing partners, including those of the United Nations, including UNDP, or UN Member States. Any errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. Reproduction -

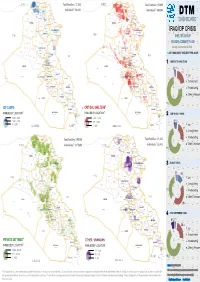

20141214 04 IOM DTM Repor

TURKEY Zakho Amedi Total Families: 27,209 TURKEY Zakho Amedi TURKEY Total Families: 113,999 DAHUK Mergasur DAHUK Mergasur Dahuk Sumel 1 Sumel Dahuk 1 Soran Individual : 163,254 Soran Individuals : 683,994 DTM Al-Shikhan Akre Al-Shikhan Akre Tel afar Choman Telafar Choman Tilkaif Tilkaif Shaqlawa Shaqlawa Al-Hamdaniya Rania Al-Hamdaniya Rania Sinjar Pshdar Sinjar Pshdar ERBIL ERBIL DASHBOARD Erbil Erbil Mosul Koisnjaq Mosul Koisnjaq NINEWA Dokan NINEWA Dokan Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Makhmur Sharbazher Penjwin Dabes Dabes IRAQ IDP CRISIS Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Al-Ba'aj SULAYMANIYAH Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Hatra Al-Shirqat Kirkuk Sulaymaniya Sulaymaniya KIRKUK KIRKUK Al-Hawiga Chamchamal Al-Hawiga Chamchamal DarbandihkanHalabja SYRIA Darbandihkan SYRIA Daquq Daquq Halabja SHELTER GROUP Kalar Kalar Baiji Baiji Tooz Tooz BY DISPLACEMENT FLOW Ra'ua Tikrit SYRIA Ra'ua Tikrit Kifri Kifri January to December 9, 2014 SALAH AL-DIN Haditha Haditha SALAH AL-DIN Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Samarra Al-Daur Khanaqin Al-Ka'im Al-Ka'im Al-Thethar Al-Khalis Al-Thethar Al-Khalis % OF FAMILIES BY SHELTER TYPE AS OF: DIYALA DIYALA Ana Balad Ana Balad IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Al-Muqdadiya IRAN Heet Al-Fares Heet Al-Fares Tar m ia Tarm ia Ba'quba Ba'quba Adhamia Baladrooz Adhamia Baladrooz Kadhimia Kadhimia JANUARY TO MAY CRISIS KarkhAl Resafa Ramadi Ramadi KarkhAl Resafa 1 Abu Ghraib Abu Ghraib BAGHDADMada'in BAGHDADMada'in ANBAR Falluja ANBAR Falluja Mahmoudiya Mahmoudiya Badra Badra 2% 1% Al-Azezia Al-Azezia Al-Suwaira Al-Suwaira Al-Musayab Al-Musayab 21% Al-Mahawil -

Mosul Response Dashboard 20 Aug 2017

UNHCR Mosul Emergency Response Since October 2016 23 August 2017 UNHCR Co-coordinated Clusters: 1,089,564 displaced since 17 October 2016 Camp/Site Plots Tents Complete + of whom 838,608 are NFI Kits WƌŽƚĞĐƟŽŶ ƐƟůůĐƵƌƌĞŶƚůLJĚŝƐƉůĂĐĞĚ & ;ŽͲĐŽŽƌĚŝŶĂƚĞĚďLJhE,ZΘZͿ Targets:44,000 60,000 87,500 ƐƐŝƐƚĞĚďLJhE,Z KĐĐƵƉŝĞĚ DistribƵted 8,931 10,586 SŚĞůƚĞƌΘE&/ 8,931 3,360 (Co-coordinated ďLJhE,ZΘEZͿ 454,098 144,703 20,576 16,849 ( 17,294 16,398 ŝŶĚŝǀŝĚƵĂůƐ ŝŶĚŝǀŝĚƵĂůƐ Developed Plots Available assisted assisted Camp ŽŽƌĚŝŶĂƟŽŶΘ 34,671 73,554 ĂŵƉDĂŶĂŐĞŵĞŶƚ in camps ŽƵƚŽĨĐĂŵƉƐ 6,187 34,220 /ŶĐůƵĚĞƐĐŽŶŇŝĐƚͲĂīĞĐƚĞĚ EĞǁƌĞƋƵŝƌĞŵĞŶƚƐ EĞǁƌĞƋƵŝƌĞŵĞŶƚƐ ! ;ŽͲĐŽŽƌĚŝŶĂƚĞĚďLJhE,ZΘ/KDͿ ƉŽƉƵůĂƟŽŶǁŚŽǁĞƌĞ ŶĞǀĞƌĚŝƐƉůĂĐĞĚ in 2017 in 2017 Derkar dhZ<z Batifa 20km UNHCR Protection Monitoring for Mosul Response Zakho Amadiya Amedi Soran Mergasur Dahuk Ü 47,478 HHs Assessed Sumel Dahuk ^zZ/EZ 212,978 IndividƵals ZWh>/ DAHUK Akre Choman Mosul Dam Lake Shikhan Soran Choman Amalla ISLADIC Mosul Dam Nargizlia 1 B Nargizlia 2 ZEPUBLIC Tilkaif B Telafar Zelikan (n(new) OF IZAN QaymawaQ (Zelikan) B Shaqlawa 58,954 60,881 48,170 44,973 NINEWA HamdaniyaHdHamdaddaa iyaiyyay Al Hol HasanshamHaasasanshams U2 campp MosulMosuMosMooosssuulul HasanshamHasansham U3 Rania BartellaBartelllalaB B Pshdar Mosul BBBHhM2Hasanshamaanshnnssh M2 KhazerKhazehaha M1 Plots in UNHCR Constructed Camps Sinjar BChamakorChamakor As Salamiyah S y Erbil Hammamammama Al-AlilAlil 2 Al Salamiyah 2 DUKAN Occupied Plots Developed Plots Undeveloped Plots BB B RESERVOIR HammamHammH AAlAl-Alil Alil Erbil B Al ^alamiyaŚ -

Pdf Projdoc.Pdf

ABOUT US our history Re:Coded is nonprofit organization registered in the United States, with operations in Iraq, Turkey and Yemen. Our mission is to prepare conflict-affected and underserved youth to enter the digital economy as software developers, entrepreneurs and tech leaders in their communities. Since 2017, we have trained more than 500 children and young adults how to code. Over 88% of our graduates, seeking employment after graduation find technical work within 6 months. Our activities include coding bootcamps, entrepreneurship training, a co-working space, and tech workshops and events. OUR IMPACT Reach Learner Outcomes Diversity Career Outcomes 2971 83% 44% 88% Number of candidates who Average daily attendance Female participants Of job placement* applied for the program Graduates actively seeking employment 6 96% 44% months after graduation 220 Of modules completed in Refugee or Internally Number of students the curriculum Displaced Person accepted into the program 86% 192 Trainer satisfaction Number of graduates 2019 Programs Launching of Re:Coded House, a co-working space in Erbil, Iraq, for innovative and socially- minded professionals. Re:Coded House is a place to convene and connect with training spaces, meetings rooms, a maker space, and desks for up to 60 members. Locations: Erbil, Baghdad, Basra, Qaraqosh Programs: 01 Coding Bootcamp 01 Tech Startup Academy 01 Maker Academy Iraq 10+ Workshops on Programming 10+ Workshops on Life Skills 02 Hackathons Beneficiaries: 500+ people Locations: Istanbul, Gaziantep Locations: Sana'a Programs: 02 Coding Bootcamps Programs: 5+ Workshops on Programming 5+ Workshops on Life Skills Beneficiaries: 25 people Turkey Beneficiaries: 200+ people Yemen 12 THE RE:CODED EFFECT EDUCATION THAT DELIVERS CAREER ORIENTATED Students gain the technical and power skills they We provide our students specialized career prep need to work as web or mobile developers in the and apprenticeship opportunities to ensure that best companies locally or abroad. -

Poverty Rates

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Mapping Poverty inIraq Mapping Poverty Where are Iraq’s Poor: Poor: Iraq’s are Where Acknowledgements This work was led by Tara Vishwanath (Lead Economist, GPVDR) with a core team comprising Dhiraj Sharma (ETC, GPVDR), Nandini Krishnan (Senior Economist, GPVDR), and Brian Blankespoor (Environment Specialist, DECCT). We are grateful to Dr. Mehdi Al-Alak (Chair of the Poverty Reduction Strategy High Committee and Deputy Minister of Planning), Ms. Najla Ali Murad (Executive General Manager of the Poverty Reduction Strategy), Mr. Serwan Mohamed (Director, KRSO), and Mr. Qusay Raoof Abdulfatah (Liv- ing Conditions Statistics Director, CSO) for their commitment and dedication to the project. We also acknowledge the contribution on the draft report of the members of Poverty Technical High Committee of the Government of Iraq, representatives from academic institutions, the Ministry of Planning, Education and Social Affairs, and colleagues from the Central Statistics Office and the Kurdistan Region Statistics during the Beirut workshop in October 2014. We are thankful to our peer reviewers - Kenneth Simler (Senior Economist, GPVDR) and Nobuo Yoshida (Senior Economist, GPVDR) – for their valuable comments. Finally, we acknowledge the support of TACBF Trust Fund for financing a significant part of the work and the support and encouragement of Ferid Belhaj (Country Director, MNC02), Robert Bou Jaoude (Country Manager, MNCIQ), and Pilar -

Iraq's Displacement Crisis

CEASEFIRE centre for civilian rights Lahib Higel Iraq’s Displacement Crisis: Security and protection © Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Rights Group International March 2016 Cover photo: This report has been produced as part of the Ceasefire project, a multi-year pro- gramme supported by the European Union to implement a system of civilian-led An Iraqi boy watches as internally- displaced Iraq families return to their monitoring of human rights abuses in Iraq, focusing in particular on the rights of homes in the western Melhaniyeh vulnerable civilians including vulnerable women, internally-displaced persons (IDPs), neighbourhood of Baghdad in stateless persons, and ethnic or religious minorities, and to assess the feasibility of September 2008. Some 150 Shi’a and Sunni families returned after an extending civilian-led monitoring to other country situations. earlier wave of displacement some two years before when sectarian This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union violence escalated and families fled and the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. The con- to neighbourhoods where their sect was in the majority. tents of this report are the sole responsibility of the publishers and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. © Ahmad Al-Rubaye /AFP / Getty Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is a new initiative to develop ‘civilian-led monitoring’ of violations of international humanitarian law or human rights, to pursue legal and political accountability for those responsible for such violations, and to develop the practice of civilian rights. -

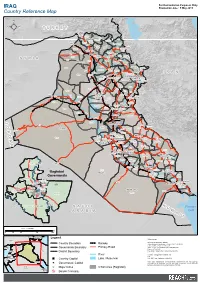

Country Reference Map

For Humanitarian Purposes Only IRAQ Production date : 5 May 2015 Country Reference Map T U R K E Y Ibrahim Al-Khalil (Habour) Zakho Zakho Amedi Dahuk Amedi Mergasur Dahuk Sumel Dahuk Rabia Mergasur Soran Sumel Shikhan Akre Haji Omaran Shikhan Akre Soran Telafar Choman Tilkaif Tilkaif Choman Shaqlawa Telafar Shaqlawa Sinjar Mosul Hamdaniya Rania Pshdar Sinjar Hamdaniya Erbil Ranya Qalat Erbil Dizah SYRIA Ba'aj Koisnjaq Mosul Erbil Ninewa Koisnjaq Dokan Baneh Dokan Makhmur Sharbazher Ba'aj Chwarta Penjwin Dabes Makhmur Penjwin Hatra Dabes Kirkuk Sulaymaniyah Chamchamal Shirqat Kirkuk IRAN Sulaymaniyah Hatra Shirqat Hawiga Daquq Sulaymaniyah Kirkuk Halabja Hawiga Chamchamal Darbandihkan Daquq Halabja Halabja Darbandikhan Baiji Tooz Khourmato Kalar Tikrit Baiji Tooz Ru'ua Kifri Kalar Tikrit Ru'ua Ka'im Salah Daur Kifri Ka'im Ana Haditha Munthiriya al-Din Daur Khanaqin Samarra Samarra Ka'im Haditha Khanaqin Balad Khalis Diyala Thethar Muqdadiya Balad Ana Al-Dujayl Khalis Muqdadiya Ba`aqubah Mandali Fares Heet Heet Ba'quba Baladrooz Ramadi Falluja Baghdad J Ramadi Rutba Baghdad Badra O Baramadad Falluja Badra Anbar Suwaira Azezia Turaybil Azezia R Musayab Suwaira Musayab D Ain Mahawil Al-Tamur Kerbala Mahawil Wassit Rutba Hindiya Na'miya Kut Ali Kerbala Kut Al-Gharbi A Ain BabylonHilla Al-Tamur Hindiya Ali Hashimiya Na'maniya Al-Gharbi Hashimiya N Kerbala Hilla Diwaniya Hai Hai Kufa Afaq Kufa Diwaniya Amara Najaf Shamiya Afaq Manathera Amara Manathera Qadissiya Hamza Rifa'i Missan Shamiya Rifa'i Maimouna Kahla Mejar Kahla Al-Kabi Qal'at Hamza -

The Application of English Theories to Sorani Phonology

Durham E-Theses The Application of English Theories to Sorani Phonology AHMED, ZHWAN,OTHMAN How to cite: AHMED, ZHWAN,OTHMAN (2019) The Application of English Theories to Sorani Phonology, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13290/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk The Application of English Theories to Sorani Phonology Zhwan Othman Ahmed A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Modern Languages and Cultures Durham University 2019 Abstract This thesis investigates phonological processes in Sorani Kurdish within the framework of Element Theory. It studies two main varieties of Sorani spoken in Iraq which are Slemani and Hawler. Since the phonology of SK is one of the least studied areas in Kurdish linguistics and the available studies provide different accounts of its segments, I start by introducing the segmental system of the SK dialect group.