How Intercountry Adoption Propels the Practices of Child Trafficking and Exploitation in Kenya. Beatrice Kavata Ngungua Ad102129

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

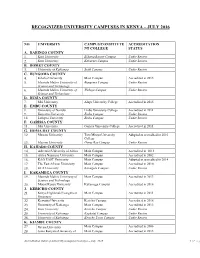

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

Prof. William Wanjala Toili Date of Birth

1 PROFILE OF WILLIAM WANJALA TOILI PERSONAL DETAILS FULL NAME : PROF. WILLIAM WANJALA TOILI DATE OF BIRTH : 18TH APRIL 1953 NATIONALITY : Kenyan, ID NO 6140801; Passport No. A1186400 MARITAL STATUS : Married PLACE OF WORK: Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology (MMUST) Department of Science and Mathematics Education P.O. Box 190 -50100 KAKAMEGA, KENYA Tel. (056) 20724, Mobile 0718-504614/0775-218078 Fax (056) 30153 E-mail: [email protected] CURRENT APPOINTMENT: Associate Professor in Science and Environmental Education, Department of Science and Mathematics Education Masinde Muliro University of Science & Technology CAREER GOAL : To effectively conduct research, teach and disseminate knowledge and skills in order to empower humanity to realize their potential and control their destiny. SPECIAL SKILLS - Communicates well in English, Kiswahili and Luhya - Setting personal and organizational goals and effectively implementing them. - Conducting informed guidance and counseling of both youths and adults. - Preparing effective academic and small scale research proposals and writing comprehensive reports - Developing and evaluating academic programs at all levels and sectors of education. - Citizenship action skills such as mobilizing people to conduct informed environmental conservation. - Organizing successful seminars/workshops/training. - Preparing effective institutional strategic plans. EDUCATION AND ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION 1994 – 2001: Doctor of Philosophy in Science and Environmental Education; Maseno University, Kenya. Awarded November, 2001 1988 - 1989 : Master of Education in Science and Environmental Education, School of Education, University of Leeds, England, U.K. Awarded May, 1990. 1987 : Postgraduate Certificate in Environmental Education, Moi University, Kenya. Awarded 1993. 1 2 1983 - 1985 : Master of Education in Teacher Education (Science Education and Curriculum Development); University of Nairobi, Kenya. -

Is It Terrorism Or Economic Sabotage?

KHRC’s 2014-2018 Also Inside: The Truth about Marriage Bill; Strategic Plan: discussed by the Kenyatta "...The KHRC is permanent, University Legal Aid Clinic. The issue of Anglo-Leasing, By irreversible and Mr. Joseph Agwata (KUSOL irrevocable.” Alumni) Page | 1 Is It Terrorism or Economic Sabotage? Join the conversation facebook.com/kenyanlegal; twitter.com/The_Kenyan_Legal There’s more things in Heaven and Earth than what's dreamt of in Philosophy, and on Page | 2 the other hand, Religion is what keeps the poor from killing the rich, but certainly, is there more to the Islam religion and the Salafi philosophy/ideology than to just killing in the name of ‘God’? and why Kenya in particular? What makes the other East African countries out of the premium? Find out in this issue. Now, since the whole world is watching, we at Kenyan Legal want to always give you something special; something good, like a river glory, and in that spirit, I introduce to you our panel members of the Reviewer Feedback Programme, the Kenyatta University Legal Aid Clinic, and the strategic Plan 2014-2018 of the Kenya Human Rights Commission(KHRC),and as Prof. Makau Mutua once stated,"...The KHRC is permanent, irreversible and irrevocable.”, we share the same optimism. Still progressing to give you nothing short of the best, this is Issue #8 of the Kenyan Legal Magazine; Real Kenya, Real Issues. Welcome. REGARDS, Michael Michael Opondo O. www.michaelopondo.wordpress.com Managing Editor, KENYAN LEGAL The Kenyan Legal Team The Branch Co-Ordinators The Secretariat Kenneth Kimathi: Kenyatta University Michael O. -

Influence of Media Training on the Competence of Journalists in Kenya

Influence of Media Training on the Competence of Journalists in Kenya: Perceptions of Standard Group Limited Managers and Senior Journalists Amukuzi, Marion1, Kuria, Githinji Martin2 Riara University, Kenya1, Karatina University, Kenya2 Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract A number of researches have indicated that training institutions have failed to impart skills and knowledge to students that would be transferred to the industry upon graduation and employment, hence the quality of journalists graduating is wanting. The purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of media training on the competency of journalists in Kenya. Curricula were sampled from selected Kenyan universities and adequacy of training material investigated. Non-probability sampling procedure involving purposive and snow-ball sampling methods were used to identify the 9 participants comprising media managers and senior journalists in one media organization. Data was analysed thematically and presented in a narrative form in accordance with the themes. According to the SG media managers and senior journalists, journalists trained in Kenya lack practical skills required in the job market. Consequently, media houses are recruiting graduates in other disciplines such as English, Medicine, and Law while others have resorted to re-training the new recruits. It is recommended that media training institutions, regulators and other stakeholders should revamp existing curricula with the view to making them competency based. Keyword: Influence of Media, Journalists, Perceptions Standard Group Limited, Managers and Senior Journalists. Introduction and Background of the Study The performance of media in Kenya is closely related to the level of journalism training where appropriate training provides students with knowledge and skills to write accurate, fair, balanced and impartial stories (Mbeke, 2010). -

BUSALILE JACK MWIMALI B.A.L., LL.B., LL.M., Phd, AIII, ADV

BUSALILE JACK MWIMALI B.A.L., LL.B., LL.M., PhD, AIII, ADV. ADDRESS Permanent Office P.O. Box 184, Goretti Munialo Mwimali & Co Adv Village Market, Uchumi House, 14th Flr Nairobi, Kenya P.O. Box 722 - 00100 Tel. +254720741027 Nairobi, Kenya Nationality: Kenyan Date of Birth: 25th Jan 1977 Gender: Male Marital Status: Married with one son Religion: Christian; Protestant OBJECTIVE To pursue an intellectually stimulating career and actualise a self-motivated professional life, in legal practice and research which would ensure a productive and gratifying outcome beneficial to me, my family and the society in general. 1 BACKGROUND Dr Mwimali is a law lecturer, an advocate of the High Court of Kenya and a human-rights practitioner, with an interest in legal education, litigation, and human rights advocacy. He has taught numerous courses in law at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology; the University of Nairobi School of Law; Kenyatta University School of Law; Birmingham Law School; Riara Law School; KCA University; and Nazarene University School of Law. He is also experienced in human rights advocacy having worked for a number of Non-Governmental Human Rights Organisations. He is currently an advocate practicing with the law firm of Goretti Munialo Mwimali & Co. Advocates. He also serves as a senior lecturer at the School of Law, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology and a part-time lecturer at Riara University School of Law. He doubles up as an international Consulting Associate with Odokel Opolot Advocates, Uganda. WORK EXPERIENCE Sept 2013 to Date: Senior Lecturer, School of law, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Teaching: Constitutional Law; Human Rights Law; Family Law; Insurance Law; Land Law; Equity; and Law of Trusts. -

Factors Influencing Students' Performance in the Kenyan Bar Examination and Proposed Interventions

KENYA SCHOOL OF LAW Factors Influencing Students’ Performance in the Kenyan Bar Examination and Proposed Interventions Final Report September 2019 i Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................... v Abbreviations and Acronyms ......................................................................... xi 1 Background and Study Context ............................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................. 1 1.2 Interpretation of Terms of Reference ............................................. 4 1.3 Methodological Approach ............................................................... 4 2 Evolution of Legal Education in Kenya and Institutional Frameworks ......... 9 2.1 Development of Legal Education in Kenya ...................................... 9 2.2 Functions of Legal Education System in Kenya ............................... 11 2.3 Institutional Framework for Legal Education and Training in Kenya . 11 2.3.1 The Council of Legal Education ..................................................12 2.3.2 The Kenya School of Law ..........................................................15 2.3.3 Restructuring of the Kenya School of Law and Council of Legal Education .............................................................................................16 2.3.4 The Law Society of Kenya ..........................................................17 2.3.5 The Commission for University -

Where Is FIDA?

Page | 1 KENYAN WOMEN AT DUSK: Where is FIDA? Also Inside: Main Party behind Wanguru Sacking Agenda Raila’s Return and what it means to the Ruling Join the conversation facebook.com/kenyanlegal;Coalition twitter.com/The_Kenyan_Legal Tribalism a Cake Baked By the Government The main gender identities in a family/society setting need not necessarily be positively Page | 2hostile towards each other as none of them can subsist alone but the current sound of FIDA’s silence is rather surprising because gender-based violence against women is so clearly an increasing problem in the country Kenya now taking the form of normalcy-as being part of a Kenyan woman’s life, but, the farther we penetrate into the primitive history of thought, the farther we find ourselves from a conception of progress and development which all along it resembles. To ask for action from the government is rather rhetoric but from FIDA-Kenya, I cannot help asking for something more, for some central notion which shall account not only for the elimination of gender based violence but also for its permanence. It may be doubted whether this quest can be successful. As time progresses, so do we; or rather we strive to. I therefore welcome you to the Ninth issue of Kenyan Legal magazine; this is it-It’s Real Kenya, Real Issues. Be my guest. REGARDS, Michael Michael Opondo O. www.michaelopondo.wordpress.com Managing Editor, KENYAN LEGAL The Kenyan Legal Team The Branch Co-Ordinators The Secretariat Kenneth Kimathi: Kenyatta University Michael O. Opondo: Managing Editor. (School of Law) Sheila Mokaya: Assistant Editor. -

Illusionsof Location Theory

ILLUSIONS OF LOCATION THEORY Consequences for Blue Economy in Africa Edited by Francis Onditi Riara University, Kenya and Douglas Yates American Graduate School, Paris, France Series in Politics Copyright © 2021 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Politics Library of Congress Control Number: 2020943381 ISBN: 978-1-64889-021-5 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press using elements designed by Freepik. Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Foreword ix Narnia Bohler-Muller Human Sciences Research Council; University of Fort Hare; University of Free State -

Detailed Table of Contents

Detailed Table of Contents Foreword.............................................................................................................. xv Preface................................................................................................................xvii Acknowledgment............................................................................................... xxv Chapter 1 Mobile.Money.Transfer:.Reshaping.Remittances.and.Bridging.Financial. Inclusion.in.Africa.and.Beyond..............................................................................1 Martin Gachukia, Riara University, Kenya The.chapter.reviews.the.growth.of.mobile.money.transactions.(MMTs).and.their. effect.on.international.remittances.and.financial.inclusion..The.novelty.of.MMTs.is. its.widening.adaptation.beyond.Sub-Saharan.Africa.with.increased.confidence.in.use. of.MMTs.by.international.humanitarian.agencies.and.governments.in.reaching.out. to.citizenry.through.government-to-people.(G2P).as.well.as.people-to-government. (P2G).payment.platforms..The.chapter.is.conceptualized.on.the.emergent.themes. emanating.from.the.World.Bank.data.under.the.G20.financial.inclusion.indicators. in. 60. countries. with. remarkable. MMTs. per. 100,000. adults.. Emergent. findings. from.the.data.indicates.of.MMT.benefits.to.small.countries.such.as.the.Pacific. Island.countries,.benign.economic.policies.under.West.African.countries,.increased. uptake.of.cash.and.voucher.transfers.through.humanitarian.support,.and.the.pursuit. of.cashless.economy.through.mobile.wallets..In.essence,.the.growth.of.MMTs.is. -

Award Papers

International Association of Law Schools 2015 Annual Meeting Award Papers Developing Approaches and Standards for a Global Legal Education Hosted by: IE University, Law School 27th – 29th October 2015 Segovia, Spain International Association of Law Schools 2015 Annual Meeting Award Papers Faculty Innovative Curriculum Awards Michele DeStefano, University of Miami School of Law: Law without walls Anne Kotonya, Strathmore University: Globalizing the Curriculum in Emerging African Law Schools Kate Offer and Natalie Skead, The University of Western Australia: Learning Law through a Lens: Using Visual Media to Support Student Learning and Skills Development in Law Collaborative Research Award Camille Davidson and Kama Pierce, Charlotte School of Law: Are You on the Right Track? Francis Kariuki Kamau and Beatrice Kioko, Strathmore University: In Search for an Alternative Conceptual and Methodological Framework in Law School Teaching and Scholarship Student Engagement Award Taylor Gissell, University of Houston Law Center: Lawyer Substance Abuse—Reducing the True Cost of an American Legal Education Olive Mumbo, Strathmore University: Legal Education in my Country, a Law Student’s Perspective Clare Smyth, The University of Adelaide: Global Approaches to Legal Education Faculty Innovative Curriculum Awards IALS: The Faculty Innovative Curriculum Awards Abstract Submission LawWithoutWalls: 750+ Change Agents, 30 Law & Business Schools, 15 Countries, 6 Continents Globalizing the Law School Curriculum and Creating the Future of Law Today -

View Full CV

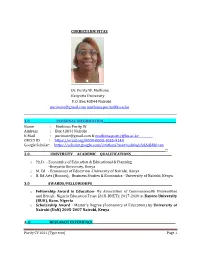

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Purity W. Muthima Kenyatta University P.O. Box 43844 Nairobi [email protected] [email protected] _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1.0 PERSONAL INFORMATION__________________________________________________ Name : Muthima Purity W. Address : Box 43844 Nairobi E-Mail : [email protected] & [email protected] ORCiD ID : https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1035-9140 Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=qck0qlcAAAAJ&hl=en _________________________________________________________________________________________________-- 2.0. UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS____________________________ o Ph.D. - Economics of Education & Educational & Planning -Kenyatta University, Kenya o M. Ed - Economics of Education -University of Nairobi, Kenya o B. Ed Arts (Honors), Business Studies & Economics - University of Nairobi, Kenya 3.0 AWARDS/FELLOWSHIPS_______________________________________________________ o Fellowship Award in Education- By Association of Commonwealth Universities and British- Nigeria Education Trust (ACU-BNET): 2017-2020 at Bayero University (BUK), Kano, Nigeria o Scholarship Award - Master’s Degree (Economics of Education) by University of Nairobi (UoN) 2005-2007 Nairobi, Kenya 4. 0 RESEARCH EXPERIENCE_________________________________________________________ Purity CV 2021 [Type text] Page 1 o Principal Investigator : -Currently undertaking an impact evaluation study on ‘Enhancing women and girls work readiness through Apprenticeship, -

Institutions Accreditation Status As at 31 December 2016

INSTITUTIONS ACCREDITATION STATUS AS AT 31 DECEMBER 2016 Accreditation is a validation process by which training institutions are evaluated against established standards to ensure a high level of educational quality. It is usually a voluntary process. FULL ACCREDITATION 1. Achievers College of Professionals - Embu Alphax College - Eldoret 2. African Institute of Research and Development Studies - Eldoret 3. African Institute of Research and Development Studies - Kisumu 4. Bartek Institute - Eldama Ravine 5. Bartek Institute - Kabarnet 6. Catholic University of Eastern Africa, Main Campus - Nairobi 7. Century Park College - Machakos 8. College of Human Resource Management - Nairobi 9. Dedan Kimathi University of Technology, Nyeri Town Campus - Nyeri 10. East Africa School of Management - Nairobi 11. Eldoret Polytechnic - Eldoret 12. Embu College - Embu 13. Excel Institute of Professionals - Thika 14. Fomic Business School, Buea - Cameroon 15. Graffins College - Nairobi 16. Gusii Institute of Technology - Kisii 17. Institut Polytechnique De Byumba, Byumba - Rwanda 18. Institut Professionnel De Certification - Douala, Cameroon 19. Kitale Technical Training Institute - Kitale 20. Jaramogi Oginga University of Science and Technology - Bondo 21. Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Main Campus - Juja 22. Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Nakuru CBD Campus - Nakuru 23. Kabete Technical Training Institute - Nairobi 24. Kaiboi Technical Training Institute - Eldoret 25. KCA University Kisumu Campus - Kisumu 26. KCA University, Main Campus - Nairobi 27. Kenya Institute of Management - Nairobi 28. Kenya School of Credit Management - Nairobi 29. Kenya School of Government - Mombasa 30. Kenya School of Government - Nairobi 31. Kiambu Institute of Science and Technology - Kiambu 32. Kibabii University College - Bungoma Page 1 of 5 33.