The Right to Freedom of Expression and Its Role in Political Transformation In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

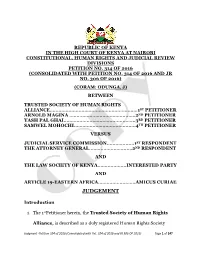

PETITION No 314 of 2016 (With Pet 324 of 16 and JR 306 Of

REPUBLIC OF KENYA IN THE HIGH COURT OF KENYA AT NAIROBI CONSTITUTIONAL, HUMAN RIGHTS AND JUDICIAL REVIEW DIVISIONS PETITION NO. 314 OF 2016 (CONSOLIDATED WITH PETITION NO. 314 OF 2016 AND JR NO. 306 OF 2016) (CORAM: ODUNGA, J) BETWEEN TRUSTED SOCIETY OF HUMAN RIGHTS ALLIANCE…………………………………….……..……….1ST PETITIONER ARNOLD MAGINA ………….……………………………2ND PETITIONER YASH PAL GHAI…………………………………………..3RD PETITIONER SAMWEL MOHOCHI…………………………………….4TH PETITIONER VERSUS JUDICIAL SERVICE COMMISSION………….…...1ST RESPONDENT THE ATTORNEY GENERAL……………………..….2ND RESPONDENT AND THE LAW SOCIETY OF KENYA……..…………INTERESTED PARTY AND ARTICLE 19-EASTERN AFRICA……………………..AMICUS CURIAE JUDGEMENT Introduction 1. The 1stPetitioner herein, the Trusted Society of Human Rights Alliance, is described as a duly registered Human Rights Society Judgment -Petition 324 of 2016 (Consolidated with Pet. 324 of 2016 and JR 306 OF 2016) Page 1 of 247 within the Republic of Kenya with the mandate of protection of constitutionalism, the rule of law, democracy and human rights. 2. The 2nd Petitioner, Arnold Magina, is an advocate of the High Court of Kenya pursuing a Master of Laws Degree at the University of Nairobi. 3. The 3rd Petitioner, Yash Pal Ghai, is a Kenyan citizen and a retired professor of law and former Chairperson of the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission. 4. The 4th Petitioner, Samwel Mohochi,isa Kenyan citizen and advocate of the High Court of Kenya. 5. The 1stRespondent, the Judicial Service Commission, (also hereinafter referred to as “the Commission” or “the JSC”) is a Constitutional Commission established under Articles 171 and 248(2)(e) of the Constitution. It is also a corporate body under Article 253 of the Constitution capable of suing and being sued and is, pursuant to Article 172 of the Constitution, constitutionally charged with promoting and facilitating the independence and accountability of the judiciary and the efficient, effective and transparent administration of justice including recommending to the President persons for Judgment -Petition 324 of 2016 (Consolidated with Pet. -

The Appointment, Tenure and Removal of Judges Under Commonwealth

The The Appointment, Tenure and Removal of Judges under Commonwealth Principles Appoin An independent, impartial and competent judiciary is essential to the rule tmen of law. This study considers the legal frameworks used to achieve this and examines trends in the 53 member states of the Commonwealth. It asks: t, Te ! who should appoint judges and by what process? nur The Appointment, Tenure ! what should be the duration of judicial tenure and how should judges’ remuneration be determined? e and and Removal of Judges ! what grounds justify the removal of a judge and who should carry out the necessary investigation and inquiries? Re mo under Commonwealth The study notes the increasing use of independent judicial appointment va commissions; the preference for permanent rather than fixed-term judicial l of Principles appointments; the fuller articulation of procedural safeguards necessary Judge to inquiries into judicial misconduct; and many other developments with implications for strengthening the rule of law. s A Compendium and Analysis under These findings form the basis for recommendations on best practice in giving effect to the Commonwealth Latimer House Principles (2003), the leading of Best Practice Commonwealth statement on the responsibilities and interactions of the three Co mmon main branches of government. we This research was commissioned by the Commonwealth Secretariat, and undertaken and alth produced independently by the Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law. The Centre is part of the British Institute of International and -

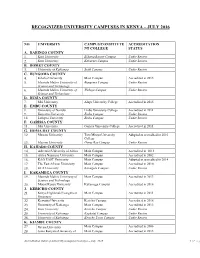

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE The Hon. Lady Justice Effie Owuor Judge of Appeal (Retired) LLB Honours, University of East Africa, Dar-Es-Salaam P.O. Box 54392-00200 Telephone 254-20-2700257 Fax 254-20-4450252 Email:[email protected] Special Awards National Recognition, EBS (Elder of Burning Spear) Recognized by the UN Secretary General as an Advocator, Campaigner and Supporter of all Children in the World in the UNICEF’S Millennium State of the World’s Children Report . September 2005 1 Profile Born on 21st September, 1943 in Kakamega, Western Province of Kenya. A graduate of the University of East Africa, Dar-Es-Salaam with Bachelor of Laws degree. Has undertaken various professional and judicial seminars on law reform, women’s rights and criminal law. A distinguished career in the Attorney General’s chambers and Judiciary spanning over a period of 33 years. Rising through the ranks from a Resident Magistrate to a Judge of the Court of Appeal. The first lady to be appointed as a Puisne Judge and Judge of the Court of Appeal in the Republic of Kenya. A self-motivated retired Judge of Appeal with a wide range of experience in family, women, children, marital and succession law and has undertaken several consultancies leading to legislations in the aforementioned areas of law. Able to work on own initiative and in collaboration with technical teams from various professions. Proven leadership skills involving managing, developing and motivating teams to achieve their objectives. Dedicated to maintaining high quality standards and achieving set targets. Key public positions held: - Commissioner of Kenya Law Reform Commission - Founding Member and Chairperson of the Kenya Women’s Judges Association, past patron of the association. -

Prof. William Wanjala Toili Date of Birth

1 PROFILE OF WILLIAM WANJALA TOILI PERSONAL DETAILS FULL NAME : PROF. WILLIAM WANJALA TOILI DATE OF BIRTH : 18TH APRIL 1953 NATIONALITY : Kenyan, ID NO 6140801; Passport No. A1186400 MARITAL STATUS : Married PLACE OF WORK: Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology (MMUST) Department of Science and Mathematics Education P.O. Box 190 -50100 KAKAMEGA, KENYA Tel. (056) 20724, Mobile 0718-504614/0775-218078 Fax (056) 30153 E-mail: [email protected] CURRENT APPOINTMENT: Associate Professor in Science and Environmental Education, Department of Science and Mathematics Education Masinde Muliro University of Science & Technology CAREER GOAL : To effectively conduct research, teach and disseminate knowledge and skills in order to empower humanity to realize their potential and control their destiny. SPECIAL SKILLS - Communicates well in English, Kiswahili and Luhya - Setting personal and organizational goals and effectively implementing them. - Conducting informed guidance and counseling of both youths and adults. - Preparing effective academic and small scale research proposals and writing comprehensive reports - Developing and evaluating academic programs at all levels and sectors of education. - Citizenship action skills such as mobilizing people to conduct informed environmental conservation. - Organizing successful seminars/workshops/training. - Preparing effective institutional strategic plans. EDUCATION AND ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION 1994 – 2001: Doctor of Philosophy in Science and Environmental Education; Maseno University, Kenya. Awarded November, 2001 1988 - 1989 : Master of Education in Science and Environmental Education, School of Education, University of Leeds, England, U.K. Awarded May, 1990. 1987 : Postgraduate Certificate in Environmental Education, Moi University, Kenya. Awarded 1993. 1 2 1983 - 1985 : Master of Education in Teacher Education (Science Education and Curriculum Development); University of Nairobi, Kenya. -

Is It Terrorism Or Economic Sabotage?

KHRC’s 2014-2018 Also Inside: The Truth about Marriage Bill; Strategic Plan: discussed by the Kenyatta "...The KHRC is permanent, University Legal Aid Clinic. The issue of Anglo-Leasing, By irreversible and Mr. Joseph Agwata (KUSOL irrevocable.” Alumni) Page | 1 Is It Terrorism or Economic Sabotage? Join the conversation facebook.com/kenyanlegal; twitter.com/The_Kenyan_Legal There’s more things in Heaven and Earth than what's dreamt of in Philosophy, and on Page | 2 the other hand, Religion is what keeps the poor from killing the rich, but certainly, is there more to the Islam religion and the Salafi philosophy/ideology than to just killing in the name of ‘God’? and why Kenya in particular? What makes the other East African countries out of the premium? Find out in this issue. Now, since the whole world is watching, we at Kenyan Legal want to always give you something special; something good, like a river glory, and in that spirit, I introduce to you our panel members of the Reviewer Feedback Programme, the Kenyatta University Legal Aid Clinic, and the strategic Plan 2014-2018 of the Kenya Human Rights Commission(KHRC),and as Prof. Makau Mutua once stated,"...The KHRC is permanent, irreversible and irrevocable.”, we share the same optimism. Still progressing to give you nothing short of the best, this is Issue #8 of the Kenyan Legal Magazine; Real Kenya, Real Issues. Welcome. REGARDS, Michael Michael Opondo O. www.michaelopondo.wordpress.com Managing Editor, KENYAN LEGAL The Kenyan Legal Team The Branch Co-Ordinators The Secretariat Kenneth Kimathi: Kenyatta University Michael O. -

Right to Information and Parliamentary Accesibility, Accountability and Transparency

RIGHT TO INFORMATION AND PARLIAMENTARY ACCESIBILITY, ACCOUNTABILITY AND TRANSPARENCY THET KENYAN PARLIAMENT CASE RIGHT TO INFORMATION AND PARLIAMENTARY ACCESSIBILITY, ACCOUNTABILITY & TRANSPARENCY An Analysis of Access to Information, Accountability and Participation in the Kenyan Parliament By Henry Maina & Hillary Onami – Article 19 Eastern Africa Final Technical Report 2011 *IDRC Project No: 106493 * Eastern and Southern Africa Region In collaboration with Article 19 Eastern Africa ACS Plaza2nd Floor, Lenana Road P. O. Box 2653-00100 Nairobi T. +254 20 3862230-2, F. +254 20 3862231 DEFENDING FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND INFORMATION 2 | Right & Access to Information TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................4 Abbreviation and Acronyms................................................................................................................................5 Executive Summary............................................................................................................................................5 1.0 Introduction & Background ................................................................................................................7 1.0 Research Problem……..………………………………………………………………………………11 1.1 Objectives…………...........…………………………………..........................................................12 1.2 Scope of the Study.....................................................................................................................12 -

No. 1. Makhan Singh

Makhan Singh Every Inch A Fighter Reflections on Makhan Singh and the Trade Union Struggle in Kenya By Shiraz Durrani Presentation in Nairobi. Saturday August 3, 2013 Notes & Quotes Study Guide Series No. 1 (2014) Nairobi 1 Every Inch A Fighter Reflections on Makhan Singh and the Trade Union Struggle in Kenya By Shiraz Durrani Nairobi. Saturday August 3, 2013 Highlights of the presentation at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CByviTH5HC0&t=0s Notes & Quotes Study Guide Series No. 1 (2014) ISBN 978-1-869886-02-8 http://vitabooks.co.uk London. UK Photo: Makhan Singh, Nairobi, 1947. Photo by Gopal Singh Chandan a quote here.” 2 Every inch a fighter Reflections on Makhan Singh and the Trade Union Struggle in Kenya Nairobi. Saturday August 3, 2013 December this year will mark Makhan Singh's 100th birthday. To mark this anniversary and reflect on his life and contribution to Kenya’s liberation, Mau Mau Research Centre invites you to a lecture celebrating the life and work of Makhan Singh on 3rd August 2013 from 1.30pm to 4.00pm. The highlight of the day will be a presentation by our invited speaker, Shiraz Durrani titled: “Every inch a fighter Reflections on Makhan Singh and the trade union struggle in Kenya”. The lecture will take place at the Professional Centre, St John’s Gate, Parliament Road. This Study Guide is based on the presentation made at that event. Highlights of the event can be see on YouTube at the following link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CByviTH5HC0&t=0s 3 Life and times of Makhan Singh Born 27-12-1913, Gharjakh, India 1927: Came to Kenya 1931: Worked in printing press 1939: To India 1940-45: Detained in India 1947: Returned to Kenya 1950-61: Imprisoned in Kenya 4 Makhan Singh, the trade unionist March, 1935: elected Secretary of the Indian Trade Union; Aug 1949: President Influenced ITU to change to Labour Trade Union of Kenya: open it to workers irrespective of race, religion, colour. -

Restoring Integrity: an Assessment of the Needs of the Justice System in the Republic of Kenya

Restoring integrity: An assessment of the needs of the justice system in the Republic of Kenya February 2010 A Report of the International Legal Assistance Consortium and International Bar Association Human Rights Institute Supported by the Law Society of Kenya Material contained in this report may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided credit is given to the International Bar Association. Contents List of Abbreviations 6 Executive Summary 7 Chapter One – Introduction 11 1.1 The mission 11 Chapter Two – Background Information 13 2.1 Geography and demographics 13 2.2 Social and economic context 13 2.3 Contemporary political history 14 2.4 Constitutional arrangements 20 2.5 Kenya’s international legal obligations regarding due process and fair trial 23 Chapter Three – The Judicial System 25 3.1 Structure and organisation of the courts and judiciary 26 3.2 Judicial Reform Initiatives in Kenya 28 Chapter Four – The Judiciary 35 4.1 Introduction 35 4.2 Major obstacles confronting the judiciary 35 4.2.1 Constitutional framework for judicial power 35 4.2.2 Leadership of the judiciary 36 4.2.3 Composition, mandate and functioning of the Judicial Service Commission 40 4.2.4 Qualification and procedure for appointment of judges 44 4.2.5 Removal and discipline of judges 46 4.2.6 Financial autonomy 50 4.2.7 Judicial corruption 50 4.2.8 Public confidence and access to justice 52 4.3 Conclusion 54 Chapter Five – Magistrates’ Courts and the Magistracy 55 5.1 Introduction 55 5.2 Major obstacles facing the magistrates’ courts and magistracy 55 5.2.1 Structure -

Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya This Page Intentionally Left Blank Pal-Alam-00Fm.Qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page Iii

pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page i Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya This page intentionally left blank pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page iii Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya S. M. Shamsul Alam, PhD pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page iv Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya Copyright © S. M. Shamsul Alam, PhD, 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quo- tations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS. Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN-13: 978-1-4039-8374-9 ISBN-10: 1-4039-8374-7 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Alam, S. M. Shamsul, 1956– Rethinking Mau Mau in colonial Kenya / S. M. Shamsul Alam. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-4039-8374-7 (alk. paper) 1. Kenya—History—Mau Mau Emergency, 1952–1960. 2. Mau Mau History. I. Title. DT433.577A43 2007 967.62’03—dc22 2006103210 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. -

Toward a Rule of Law Culture: Practical Guide

TOWARD A RULE OF LAW CULTURE Exploring Effective Responses to Justice and Security Challenges PRACTICAL GUIDE Leanne McKay TOWARD A RULE OF LAW CULTURE Exploring Effective Responses to Justice and Security Challenges PRACTICAL GUIDE Written by Leanne McKay and edited by Adewale Ajadi and Vivienne O’Connor With contributions by Adewale Ajadi, Diane de Gramont, Hamid Khan, Rachel Kleinfeld, George Lopez, Tom Parker, and Colette Rausch UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE Washington, D.C. United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20037 www.usip.org © 2015 by the Endowment of the United States Institute of Peace. All rights reserved. First published 2015 To request permission to photocopy or reprint materials for course use, contact the Copyright Clearance Center at www.copyright.com. For print, electronic media, and all other subsidiary rights e-mail [email protected] Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standards for Information Science—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. This guide is available in English, Arabic, and French at www.usip.org. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. ii TOWARD A RULE OF LAW CULTURE A RULE OF LAW TOWARD Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. -

Decolonising Accidental Kenya Or How to Transition to a Gameb Society,The Anatomy of Kenya Inc: How the Colonial State Sustains

Pandora Papers: The Kenyatta’s Secret Companies By Africa Uncensored Published by the good folks at The Elephant. The Elephant is a platform for engaging citizens to reflect, re-member and re-envision their society by interrogating the past, the present, to fashion a future. Follow us on Twitter. Pandora Papers: The Kenyatta’s Secret Companies By Africa Uncensored President Uhuru Kenyatta’s family, the political dynasty that has dominated Kenyan politics since independence, for many years secretly owned a web of offshore companies in Panama and the British Virgin Islands, according to a new leak of documents known as the Pandora Papers. The Kenyattas’ offshore secrets were discovered among almost 12 million documents, largely made up of administrative paperwork from the archives of 14 law firms and agencies that specialise in offshore company formations. Other world leaders found in the files include the King of Jordan, the prime minister of the Czech Republic Andrej Babiš and Gabon’s President Ali Bongo Ondimba. The documents were obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and seen by more than 600 journalists, including reporters at Finance Uncovered and Africa Uncensored, as part of an investigation that took many months and spanned 117 countries. Though no reliable estimates of their net worth have been published, the Kenyattas are regularly reported to be one of the richest families in the country. The Kenyattas’ offshore secrets were discovered among almost 12 million documents, largely made up of administrative paperwork from the archives of 14 law firms and agencies that specialise in offshore company formations.