Influence of Media Training on the Competence of Journalists in Kenya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bertha Kaimenyi.Pdf

Daystar University Staff Profile Template 1. Name: Dr. Bertha Kaimenyi Doctor of Education Senior Lecturer 2. Passport photo: Passport photo here 3. Job Title and Responsibilities: Senior Lecturer School of Communication Teaching General Communication Courses and Leadership Supervising Thesis Mentoring Students Social Welfare Coordinator 4. Biography I have been a senior lecturer in General Communication Courses and Leadership and the following areas: Consultant on Leadership Management Mentoring, Coughing and Role Modeling. Facilitated trainings at KIA and other organizations. Community Involvement Served as Board Member at Kathera Girls High School Served as PTA Chairperson at Precious Blood Secondary school, RIRUTA Consultant on Balanced Lifestyle Motivational Speaker in Work-life balance, Wellness and Staff productivity, KPLC, ICPAK, Standard Chatered, Safaricom. Helping people to be productive and Discover Wellness. Facilitated trainings at British American, Eagle Africa, NSSF. Currently serving as a Director at Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA) Currently serving as a Board Member in the Meru County Council Board Member at Garissa University 5. Academic 1991 Doctor of Education, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI Qualifications: Dissertation Topic - " Issues and problems that face women Pursuing carers in Educational Administration ". Cognate in Communication. 1989 Education Specialist, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, 49104 U.S.A. 1988 Master of Arts in Educational Administration, Andrews University, Berrien Springs MIGHT 49104 U.S.A. 1985 Bachelor of Business Administration (Management), University of Eastern Africa, Eldoret, Kenya. 6. Research Interests: Holistic Education in the area of Balanced Education and Entrepreneurship 7. Publications: Book KAIMENYI B.E (2018). Growing Green Gold. Published by Big Books LTD. Nairobi, Kenya. Book Chapter KAIMENYI B.E. -

Influence of Parenting Styles on Adolescents Life-Skills

DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY INFLUENCE OF PARENTING STYLES ON ADOLESCENTS LIFE-SKILLS DEVELOPMENT: A CASE OF ADOLESCENTS ATTENDING TEENS CHURCH IN DELIVERANCE CHURCH INTERNATIONAL UMOJA, NAIROBI COUNTY by Mercy Muthoni Nzuki A thesis presented to the School of Human and Social Sciences of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Counseling Psychology October 2020 LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY APPROVAL INFLUENCE OF PARENTING STYLES ON ADOLESCENTS LIFE-SKILLS DEVELOPMENT: A CASE OF ADOLESCENTS ATTENDING TEENS CHURCH IN DELIVERANCE CHURCH INTERNATIONAL UMOJA, NAIROBI COUNTY by Mercy Muthoni Nzuki In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree. Date: _____________________________ ____________________ Susan Muriungi, PhD, 1st Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Winnie Waiyaki, PhD, 2nd Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Susan Muriungi, PhD, HoD, Counseling Psychology ______________________________ _____________________ Kennedy Ongaro, PhD, Dean, School of Human and Social Sciences ii LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY Copyright © 2020 Mercy Muthoni Nzuki iii LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY DECLARATION INFLUENCE OF PARENTING STYLES ON ADOLESCENTS LIFE-SKILLS DEVELOPMENT: A CASE OF ADOLESCENTS ATTENDING TEENS CHURCH IN DELIVERANCE CHURCH INTERNATIONAL UMOJA, NAIROBI COUNTY I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit. Signed: ______________________ Date: ___________________ Mercy Muthoni Nzuki 16-0493 iv LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My gratitude goes to the almighty God for giving me the strength to complete this study. I thank my supervisors, Dr. Susan Muriungi and Dr. -

Daystar University Staff Profile for Brenda M. Wambua

Daystar University Staff Profile For Brenda M. Wambua 1. Name: Brenda Mueni Wambua Lecturer, English and Linguistics 2. Passport photo: 3. Job Title and Responsibilities: Ms. Brenda Mueni Wambua Assistant Lecturer Language and Performing Arts, School of Communication. Teaching English (General Education Courses) and Linguistics Coordinator, Writing and Speech Centre Mentoring Students 4. Biography (About Me): I have been a teacher of English and Literature in various secondary schools: Kithangaini Secondary school (Machakos), Bishop Ngala Secondary School (Makueni) and Pangani Girls School (Nairobi). In one of the schools, Bishop Ngala Secondary School, I was a Deputy Principal. I have taught on part time basis in various universities as well: Pan African Christian University, Nazarene University, Machakos University, Kenyatta University and United States International University. I worked as an examiner as well as a Senior Examiner for Kenya National Examination Council. I am a lecturer in the Departments of Language and Performing Arts, School of Communication. I teach English and Linguistics. I also coordinate the Writing and speech Centre. I am the one in charge of time tabling classes for our department after the Head of Department has projected the classes. I train peer tutors and organize both Public Speaking and Writing competitions through the Writing and Speech Centre. I supervise Masters thesis as well. I am a trained Editor and so I edit Masters thesis and articles for Daystar Connect. I am Ph.D student at Machakos University and I have done research in various fields such as Language Planning and Policy, Academic Writing and Second Language Acquisition and Learning. -

Of Selected Standard Seven Pupils in Six Primary Schools in Lang‟Ata Constituency, Nairobi County

Daystar University Repository Effects Of Communication Involved In Play In Developing Interpersonal Skills: A Case Of Selected Standard Seven Pupils In Six Primary Schools In Lang‟Ata Constituency, Nairobi County by Redempta Oburu 11-1111 A thesis presented to the School of Communication, Language and Performing Arts of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Communication July 2017 Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository APPROVAL EFFECTS OF COMMUNICATION INVOLVED IN PLAY IN DEVELOPING INTERPERSONAL SKILLS: A CASE OF SELECTED STANDARD SEVEN PUPILS IN SIX PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN LANG‟ATA CONSTITUENCY, NAIROBI COUNTY. by Redempta Oburu 11-1111 In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the Master of Arts degree. Date: _____________________________ ____________________ Rebecca Oladipo, PhD, 1st Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Leah Komen, PhD, 2nd Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Rosemary Kowour, PhD, HOD, Communication Department _____________________________ ____________________ Levi Obonyo, PhD, Dean, School of Communication, Language and Performing Arts ii Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository Copyright ©2017 Redempta Oburu iii Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository DECLARATION EFFECTS OF COMMUNICATION INVOLVED IN PLAY IN DEVELOPING INTERPERSONAL SKILLS: A CASE OF SELECTED STANDARD SEVEN PUPILS IN SIX PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN LANG‟ATA CONSTITUENCY, NAIROBI COUNTY. I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit. Signed: ____________________________ Date: ________________ Redempta Oburu (11-1111) iv Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to specially acknowledge and thank my supervisors, Prof. -

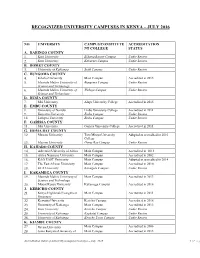

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

Examining the Relationship Between Exclusive Breastfeeding and a Mother’S Mental Health: a Case of Professional Working Mothers in Safaricom Limited, Nairobi, Kenya

DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING AND A MOTHER’S MENTAL HEALTH: A CASE OF PROFESSIONAL WORKING MOTHERS IN SAFARICOM LIMITED, NAIROBI, KENYA by Catherine Kiromo A thesis presented to the School of Human and Social Sciences of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Counselling Psychology October 2020 LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY APPROVAL EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING AND A MOTHER’S MENTAL HEALTH: A CASE OF WORKING MOTHERS IN SAFARICOM LIMITED, NAIROBI, KENYA by Catherine Kiromo 16-1896 In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the Master of Arts degree. Date: _____________________________ ___________________ Jared Menecha, PhD, 1st Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Stephen Ndegwa, PhD, 2nd Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Susan Muriungi, PhD, HOD, Psychology and Counselling _____________________________ ____________________ Kennedy Ongaro, PhD, Dean, School of Human and Social Science ii LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY Copyright © 2020 Catherine Kiromo iii LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY DECLARATION EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING AND A MOTHER’S MENTAL HEALTH: A CASE OF WORKING MOTHERS IN SAFARICOM LIMITED, NAIROBI, KENYA I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit Signed: _________________________ Date: _____________________ Catherine Kiromo 16-1896 LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I give thanks to the Almighty God for His love, care, and good health that He has granted me throughout my life, especially during this thesis journey. -

Prof. William Wanjala Toili Date of Birth

1 PROFILE OF WILLIAM WANJALA TOILI PERSONAL DETAILS FULL NAME : PROF. WILLIAM WANJALA TOILI DATE OF BIRTH : 18TH APRIL 1953 NATIONALITY : Kenyan, ID NO 6140801; Passport No. A1186400 MARITAL STATUS : Married PLACE OF WORK: Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology (MMUST) Department of Science and Mathematics Education P.O. Box 190 -50100 KAKAMEGA, KENYA Tel. (056) 20724, Mobile 0718-504614/0775-218078 Fax (056) 30153 E-mail: [email protected] CURRENT APPOINTMENT: Associate Professor in Science and Environmental Education, Department of Science and Mathematics Education Masinde Muliro University of Science & Technology CAREER GOAL : To effectively conduct research, teach and disseminate knowledge and skills in order to empower humanity to realize their potential and control their destiny. SPECIAL SKILLS - Communicates well in English, Kiswahili and Luhya - Setting personal and organizational goals and effectively implementing them. - Conducting informed guidance and counseling of both youths and adults. - Preparing effective academic and small scale research proposals and writing comprehensive reports - Developing and evaluating academic programs at all levels and sectors of education. - Citizenship action skills such as mobilizing people to conduct informed environmental conservation. - Organizing successful seminars/workshops/training. - Preparing effective institutional strategic plans. EDUCATION AND ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION 1994 – 2001: Doctor of Philosophy in Science and Environmental Education; Maseno University, Kenya. Awarded November, 2001 1988 - 1989 : Master of Education in Science and Environmental Education, School of Education, University of Leeds, England, U.K. Awarded May, 1990. 1987 : Postgraduate Certificate in Environmental Education, Moi University, Kenya. Awarded 1993. 1 2 1983 - 1985 : Master of Education in Teacher Education (Science Education and Curriculum Development); University of Nairobi, Kenya. -

Is It Terrorism Or Economic Sabotage?

KHRC’s 2014-2018 Also Inside: The Truth about Marriage Bill; Strategic Plan: discussed by the Kenyatta "...The KHRC is permanent, University Legal Aid Clinic. The issue of Anglo-Leasing, By irreversible and Mr. Joseph Agwata (KUSOL irrevocable.” Alumni) Page | 1 Is It Terrorism or Economic Sabotage? Join the conversation facebook.com/kenyanlegal; twitter.com/The_Kenyan_Legal There’s more things in Heaven and Earth than what's dreamt of in Philosophy, and on Page | 2 the other hand, Religion is what keeps the poor from killing the rich, but certainly, is there more to the Islam religion and the Salafi philosophy/ideology than to just killing in the name of ‘God’? and why Kenya in particular? What makes the other East African countries out of the premium? Find out in this issue. Now, since the whole world is watching, we at Kenyan Legal want to always give you something special; something good, like a river glory, and in that spirit, I introduce to you our panel members of the Reviewer Feedback Programme, the Kenyatta University Legal Aid Clinic, and the strategic Plan 2014-2018 of the Kenya Human Rights Commission(KHRC),and as Prof. Makau Mutua once stated,"...The KHRC is permanent, irreversible and irrevocable.”, we share the same optimism. Still progressing to give you nothing short of the best, this is Issue #8 of the Kenyan Legal Magazine; Real Kenya, Real Issues. Welcome. REGARDS, Michael Michael Opondo O. www.michaelopondo.wordpress.com Managing Editor, KENYAN LEGAL The Kenyan Legal Team The Branch Co-Ordinators The Secretariat Kenneth Kimathi: Kenyatta University Michael O. -

BUSALILE JACK MWIMALI B.A.L., LL.B., LL.M., Phd, AIII, ADV

BUSALILE JACK MWIMALI B.A.L., LL.B., LL.M., PhD, AIII, ADV. ADDRESS Permanent Office P.O. Box 184, Goretti Munialo Mwimali & Co Adv Village Market, Uchumi House, 14th Flr Nairobi, Kenya P.O. Box 722 - 00100 Tel. +254720741027 Nairobi, Kenya Nationality: Kenyan Date of Birth: 25th Jan 1977 Gender: Male Marital Status: Married with one son Religion: Christian; Protestant OBJECTIVE To pursue an intellectually stimulating career and actualise a self-motivated professional life, in legal practice and research which would ensure a productive and gratifying outcome beneficial to me, my family and the society in general. 1 BACKGROUND Dr Mwimali is a law lecturer, an advocate of the High Court of Kenya and a human-rights practitioner, with an interest in legal education, litigation, and human rights advocacy. He has taught numerous courses in law at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology; the University of Nairobi School of Law; Kenyatta University School of Law; Birmingham Law School; Riara Law School; KCA University; and Nazarene University School of Law. He is also experienced in human rights advocacy having worked for a number of Non-Governmental Human Rights Organisations. He is currently an advocate practicing with the law firm of Goretti Munialo Mwimali & Co. Advocates. He also serves as a senior lecturer at the School of Law, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology and a part-time lecturer at Riara University School of Law. He doubles up as an international Consulting Associate with Odokel Opolot Advocates, Uganda. WORK EXPERIENCE Sept 2013 to Date: Senior Lecturer, School of law, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Teaching: Constitutional Law; Human Rights Law; Family Law; Insurance Law; Land Law; Equity; and Law of Trusts. -

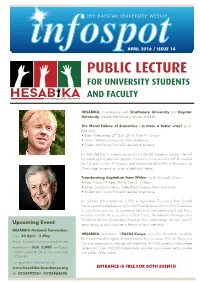

Public Lecture for University Students and Faculty

THE DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY WEEKLY APRIL 2016 / ISSUE 14 PUBLIC LECTURE FOR UNIVERSITY STUDENTS AND FACULTY HESABIKA, in partnership with Strathmore University and Daystar University, presents the following lectures and talks; The Moral Failure of Economics – Is there a better way? by Dr Paul Mills. • Date: Wednesday, 27 April, 2016. Time 9 - 12 noon • Venue: Strathmore University, Main Auditorium • Student and Faculty Picture ID required at entrance. Dr. Mills (left top) is a senior economist for the IMF based in London. He will be speaking in a personal capacity. Previous to his work in the IMF he worked for 13 years in the UK Treasury, and before that did a PhD in Economics at Cambridge University on issues of debt and interest. Transforming Capitalism from Within, by Dr. Michael Schluter. • Date: Friday, 29 April, 2016. Time 3 - 4.30pm • Venue: Daystar University, Valley Road Campus, Main Auditorium • Student and Faculty Picture ID required at entrance Dr. Schluter (left bottom) has a PhD in Agricultural Economics from Cornell University and worked previously for the World Bank as an Economics Consultant in East Africa and also as a research Fellow for the international Food Policy Research Institute. He is co-author of The R Factor, The Relational Manager, and The Relational Lens (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming). He also spent 5 Upcoming Event years setting up rural industries in Kenya in the private sector. HESABIKA National Convention, HESABIKA, an initiative of FOCUS Kenya, is a call to Kenyans to Stand Up Date: 30 April - 2 May Be Counted and be agents of transformation for our nation. -

The Kenyan Social Media Landscape: Trends and Emerging Narratives, 2020 B.Sc

The Kenyan Social Media Landscape: Trends and Emerging Narratives, 2020 B.Sc. Global Leadership and Governance M.Sc. Information Security The Kenyan Social Media Landscape: Trends and Emerging Narratives, 2020 Paul Watzlavick The Counselor for Public Affairs, U.S. Embassy, Nairobi “The United States is proud to support SIMELab and their groundbreaking research into Kenyan social media. The future is digital, so that’s where we need to be: generating innovative solutions to global challenges together.” International Symposium on Social Media USIU-Africa, Nairobi / September 11-12, 2019 “Use of digital media and social media are connected to deep-rooting changes of citizens’ self-concepts” Prof. Dr. Martin Emmer (FU Berlin) (From Left to Right) Dr. Geoffrey Sikolia, Mr. Robert Alai, Ms. Juliet Kanjukia, Ms. Ivy Mungai and Mr. Dennis Itumbi in a panel discussion on “Social Media and Governance” during the 2019 International Symposium on Social Media (From Left to Right) Mr. Alex Taremwa, Ms. Noella Musundi, Mr. David Gitari, Ms. Lucy Wamuyu and Martin Muli in a panel discussion on “Social Media versus Mainstream Media” during the 2019 International Symposium In this report Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................................10 Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................12 Key Discoveries in 2020 ...........................................................................................................................14 -

An Audit of the Kenya Slum Upgrading Programme Communication Strategy

Daystar University Repository Integrating Participatory Communication into Slum Upgrading In Kibera: An Audit of the Kenya Slum Upgrading Programme Communication Strategy by Lilian Jerotich Kimeto 07-0528 A thesis presented to the School of Communication & Languages of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Communication. February 2016 Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository INTEGRATING PARTICIPATORY COMMUNICATION INTO SLUM UPGRADING IN KIBERA: AN AUDIT OF THE KENYA SLUM UPGRADING PROGRAMME COMMUNICATION STRATEGY by Lilian Jerotich Kimeto 07-0528 In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the Master of Arts degree _____________________________ ____________________ Levi Obonyo, PhD, 1st Supervisor ______________________________ ____________________ Clayton Peel, PhD, 2nd Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Rosemary Kowuor, PhD, HoD, Communication Department _____________________________ ____________________ Levi Obonyo, PhD Dean, School of Communication & Languages Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository DECLARATION INTEGRATING PARTICIPATORY COMMUNICATION INTO SLUM UPGRADING IN KIBERA: AN AUDIT OF THE KENYA SLUM UPGRADING PROGRAMME COMMUNICATION STRATEGY I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit. Date: Signed: ____________________________ ____________________ Lilian Jerotich Kimeto (07-0528) Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have no words to express my thanksgiving to God the Almighty who has helped me complete this research. I was unwell for most of this period but God has kept me alive. I am eternally grateful to my dad, Julius Kimeto Bartilol Arap Rutto, who prayed for and encouraged me in this undertaking despite being also unwell.