Award Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

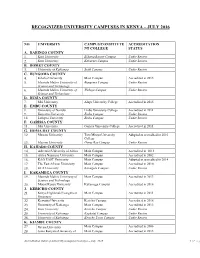

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

PROF BEN SIHANYA, JSD (STANFORD) CURRICULUM VITAE, 1/3/2021, Monday

PROF BEN SIHANYA, JSD (STANFORD) CURRICULUM VITAE, 1/3/2021, Monday © Prof Ben Sihanya, JSD & JSM (Stanford), LLM (Warwick), LLB (Nairobi), PGD Law (KSL) IP and Constitutional Professor, Public Interest Advocate and Mentor Constitutional Democracy, ©, TM, IP, Education Law, Public Interest Lawyering Commissioner for Oaths, Notary Public, Patent Agent, Author, Public Intellectual & Poet University of Nairobi Law School & Prof Ben Sihanya Advocates & Sihanya Mentoring & Innovative Lawyering Author: IP and Innovation Law in Kenya and Africa: Transferring Technology for Sustainable Development (2016; 2020); IP and Innovation Law in Kenya and Africa: Cases and Materials (forthcoming 2021); Constitutional Democracy, Regulatory and Administrative Law in Kenya and Africa Vols. 1, 2 & 3 (due 2021) [email protected]; [email protected]; url: www.sihanyaprofadvs.co.ke; www.innovativelawyering.com Nairobi; Revised 3/2/2021; 12/2/2021; 1/3/2021 1 PROF BEN SIHANYA, JSD (STANFORD) CURRICULUM VITAE 1989 to Monday, March 1, 2021 Prof Ben Sihanya, JSD & JSM (Stanford), LLM (Warwick), LLB (Nairobi), PGD Law (KSL) IP and Constitutional Professor, Public Interest Advocate and Mentor Constitutional Democracy, ©, TM, IP, Education Law, Public Interest Lawyering Commissioner for Oaths, Notary Public, Patent Agent, Author, Public Intellectual & Poet University of Nairobi Law School & Prof Ben Sihanya Advocates & Sihanya Mentoring & Innovative Lawyering Author: IP and Innovation Law in Kenya and Africa: Transferring Technology for Sustainable -

Prof. William Wanjala Toili Date of Birth

1 PROFILE OF WILLIAM WANJALA TOILI PERSONAL DETAILS FULL NAME : PROF. WILLIAM WANJALA TOILI DATE OF BIRTH : 18TH APRIL 1953 NATIONALITY : Kenyan, ID NO 6140801; Passport No. A1186400 MARITAL STATUS : Married PLACE OF WORK: Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology (MMUST) Department of Science and Mathematics Education P.O. Box 190 -50100 KAKAMEGA, KENYA Tel. (056) 20724, Mobile 0718-504614/0775-218078 Fax (056) 30153 E-mail: [email protected] CURRENT APPOINTMENT: Associate Professor in Science and Environmental Education, Department of Science and Mathematics Education Masinde Muliro University of Science & Technology CAREER GOAL : To effectively conduct research, teach and disseminate knowledge and skills in order to empower humanity to realize their potential and control their destiny. SPECIAL SKILLS - Communicates well in English, Kiswahili and Luhya - Setting personal and organizational goals and effectively implementing them. - Conducting informed guidance and counseling of both youths and adults. - Preparing effective academic and small scale research proposals and writing comprehensive reports - Developing and evaluating academic programs at all levels and sectors of education. - Citizenship action skills such as mobilizing people to conduct informed environmental conservation. - Organizing successful seminars/workshops/training. - Preparing effective institutional strategic plans. EDUCATION AND ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION 1994 – 2001: Doctor of Philosophy in Science and Environmental Education; Maseno University, Kenya. Awarded November, 2001 1988 - 1989 : Master of Education in Science and Environmental Education, School of Education, University of Leeds, England, U.K. Awarded May, 1990. 1987 : Postgraduate Certificate in Environmental Education, Moi University, Kenya. Awarded 1993. 1 2 1983 - 1985 : Master of Education in Teacher Education (Science Education and Curriculum Development); University of Nairobi, Kenya. -

Is It Terrorism Or Economic Sabotage?

KHRC’s 2014-2018 Also Inside: The Truth about Marriage Bill; Strategic Plan: discussed by the Kenyatta "...The KHRC is permanent, University Legal Aid Clinic. The issue of Anglo-Leasing, By irreversible and Mr. Joseph Agwata (KUSOL irrevocable.” Alumni) Page | 1 Is It Terrorism or Economic Sabotage? Join the conversation facebook.com/kenyanlegal; twitter.com/The_Kenyan_Legal There’s more things in Heaven and Earth than what's dreamt of in Philosophy, and on Page | 2 the other hand, Religion is what keeps the poor from killing the rich, but certainly, is there more to the Islam religion and the Salafi philosophy/ideology than to just killing in the name of ‘God’? and why Kenya in particular? What makes the other East African countries out of the premium? Find out in this issue. Now, since the whole world is watching, we at Kenyan Legal want to always give you something special; something good, like a river glory, and in that spirit, I introduce to you our panel members of the Reviewer Feedback Programme, the Kenyatta University Legal Aid Clinic, and the strategic Plan 2014-2018 of the Kenya Human Rights Commission(KHRC),and as Prof. Makau Mutua once stated,"...The KHRC is permanent, irreversible and irrevocable.”, we share the same optimism. Still progressing to give you nothing short of the best, this is Issue #8 of the Kenyan Legal Magazine; Real Kenya, Real Issues. Welcome. REGARDS, Michael Michael Opondo O. www.michaelopondo.wordpress.com Managing Editor, KENYAN LEGAL The Kenyan Legal Team The Branch Co-Ordinators The Secretariat Kenneth Kimathi: Kenyatta University Michael O. -

Influence of Media Training on the Competence of Journalists in Kenya

Influence of Media Training on the Competence of Journalists in Kenya: Perceptions of Standard Group Limited Managers and Senior Journalists Amukuzi, Marion1, Kuria, Githinji Martin2 Riara University, Kenya1, Karatina University, Kenya2 Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract A number of researches have indicated that training institutions have failed to impart skills and knowledge to students that would be transferred to the industry upon graduation and employment, hence the quality of journalists graduating is wanting. The purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of media training on the competency of journalists in Kenya. Curricula were sampled from selected Kenyan universities and adequacy of training material investigated. Non-probability sampling procedure involving purposive and snow-ball sampling methods were used to identify the 9 participants comprising media managers and senior journalists in one media organization. Data was analysed thematically and presented in a narrative form in accordance with the themes. According to the SG media managers and senior journalists, journalists trained in Kenya lack practical skills required in the job market. Consequently, media houses are recruiting graduates in other disciplines such as English, Medicine, and Law while others have resorted to re-training the new recruits. It is recommended that media training institutions, regulators and other stakeholders should revamp existing curricula with the view to making them competency based. Keyword: Influence of Media, Journalists, Perceptions Standard Group Limited, Managers and Senior Journalists. Introduction and Background of the Study The performance of media in Kenya is closely related to the level of journalism training where appropriate training provides students with knowledge and skills to write accurate, fair, balanced and impartial stories (Mbeke, 2010). -

BUSALILE JACK MWIMALI B.A.L., LL.B., LL.M., Phd, AIII, ADV

BUSALILE JACK MWIMALI B.A.L., LL.B., LL.M., PhD, AIII, ADV. ADDRESS Permanent Office P.O. Box 184, Goretti Munialo Mwimali & Co Adv Village Market, Uchumi House, 14th Flr Nairobi, Kenya P.O. Box 722 - 00100 Tel. +254720741027 Nairobi, Kenya Nationality: Kenyan Date of Birth: 25th Jan 1977 Gender: Male Marital Status: Married with one son Religion: Christian; Protestant OBJECTIVE To pursue an intellectually stimulating career and actualise a self-motivated professional life, in legal practice and research which would ensure a productive and gratifying outcome beneficial to me, my family and the society in general. 1 BACKGROUND Dr Mwimali is a law lecturer, an advocate of the High Court of Kenya and a human-rights practitioner, with an interest in legal education, litigation, and human rights advocacy. He has taught numerous courses in law at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology; the University of Nairobi School of Law; Kenyatta University School of Law; Birmingham Law School; Riara Law School; KCA University; and Nazarene University School of Law. He is also experienced in human rights advocacy having worked for a number of Non-Governmental Human Rights Organisations. He is currently an advocate practicing with the law firm of Goretti Munialo Mwimali & Co. Advocates. He also serves as a senior lecturer at the School of Law, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology and a part-time lecturer at Riara University School of Law. He doubles up as an international Consulting Associate with Odokel Opolot Advocates, Uganda. WORK EXPERIENCE Sept 2013 to Date: Senior Lecturer, School of law, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Teaching: Constitutional Law; Human Rights Law; Family Law; Insurance Law; Land Law; Equity; and Law of Trusts. -

Factors Influencing Students' Performance in the Kenyan Bar Examination and Proposed Interventions

KENYA SCHOOL OF LAW Factors Influencing Students’ Performance in the Kenyan Bar Examination and Proposed Interventions Final Report September 2019 i Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................... v Abbreviations and Acronyms ......................................................................... xi 1 Background and Study Context ............................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................. 1 1.2 Interpretation of Terms of Reference ............................................. 4 1.3 Methodological Approach ............................................................... 4 2 Evolution of Legal Education in Kenya and Institutional Frameworks ......... 9 2.1 Development of Legal Education in Kenya ...................................... 9 2.2 Functions of Legal Education System in Kenya ............................... 11 2.3 Institutional Framework for Legal Education and Training in Kenya . 11 2.3.1 The Council of Legal Education ..................................................12 2.3.2 The Kenya School of Law ..........................................................15 2.3.3 Restructuring of the Kenya School of Law and Council of Legal Education .............................................................................................16 2.3.4 The Law Society of Kenya ..........................................................17 2.3.5 The Commission for University -

Where Is FIDA?

Page | 1 KENYAN WOMEN AT DUSK: Where is FIDA? Also Inside: Main Party behind Wanguru Sacking Agenda Raila’s Return and what it means to the Ruling Join the conversation facebook.com/kenyanlegal;Coalition twitter.com/The_Kenyan_Legal Tribalism a Cake Baked By the Government The main gender identities in a family/society setting need not necessarily be positively Page | 2hostile towards each other as none of them can subsist alone but the current sound of FIDA’s silence is rather surprising because gender-based violence against women is so clearly an increasing problem in the country Kenya now taking the form of normalcy-as being part of a Kenyan woman’s life, but, the farther we penetrate into the primitive history of thought, the farther we find ourselves from a conception of progress and development which all along it resembles. To ask for action from the government is rather rhetoric but from FIDA-Kenya, I cannot help asking for something more, for some central notion which shall account not only for the elimination of gender based violence but also for its permanence. It may be doubted whether this quest can be successful. As time progresses, so do we; or rather we strive to. I therefore welcome you to the Ninth issue of Kenyan Legal magazine; this is it-It’s Real Kenya, Real Issues. Be my guest. REGARDS, Michael Michael Opondo O. www.michaelopondo.wordpress.com Managing Editor, KENYAN LEGAL The Kenyan Legal Team The Branch Co-Ordinators The Secretariat Kenneth Kimathi: Kenyatta University Michael O. Opondo: Managing Editor. (School of Law) Sheila Mokaya: Assistant Editor. -

Illusionsof Location Theory

ILLUSIONS OF LOCATION THEORY Consequences for Blue Economy in Africa Edited by Francis Onditi Riara University, Kenya and Douglas Yates American Graduate School, Paris, France Series in Politics Copyright © 2021 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Politics Library of Congress Control Number: 2020943381 ISBN: 978-1-64889-021-5 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press using elements designed by Freepik. Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Foreword ix Narnia Bohler-Muller Human Sciences Research Council; University of Fort Hare; University of Free State -

Alternative Justice Systems Baseline Policy, 2020

AlternativeALTERNATIVE JUSTICE SYSTEMS FRAMEWORKJustice SystemsPOLICY Baseline Policy traditional, informal and other mechanisms used to access justice in kenya (alternative justice systems) August 2020 Copyright © Judiciary of Kenya, 2020 Published by The Judiciary of Kenya P.O. Box 30041 - 00100, Nairobi Tel. +254 20 2221221 First edition: August 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the author or acknowledging the source except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Cover photo: Allan Gichigi/UNODC Design and layout: Amina Darani/UNODC This publication was produced with technical assistance from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and with the financial support of the European Union through the Programme for Legal Empowerment and Aid Delivery in Kenya (PLEAD). Its contents are the sole responsibility of the Judiciary of Kenya and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union or UNODC. JUSTICE AS FREEDOM1: TR ADITIONAL, INFORMAL AND OTHER MECHANISMS FOR DISPUTE RESOLUTION IN KENYA August 2020 Alternative Justice Systems Baseline Policy 1 This phrase is borrowed from Amartya Sen,Development as Freedom (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1999). Accord- ing to Sen (at page 3), development should not be gauged solely from an economic perspective or opportunities that any project is likely to create. Rather, we need to take a transformative approach. This perspective entails reviewing also rights that any initiative promotes or curtails. Aligning AJS Mechanisms and Judiciary to the Constitution of Kenya (2010) and The Judiciary’s Blueprint for Sustaining Judicial Transformation TASK FORCE ON THE TR ADITIONAL, INFORMAL AND OTHER MECHANISMS FOR DISPUTE RESOLUTION IN KENYA Letter of transmittal Date: Friday, 17th August, 2020 Hon. -

Detailed Table of Contents

Detailed Table of Contents Foreword.............................................................................................................. xv Preface................................................................................................................xvii Acknowledgment............................................................................................... xxv Chapter 1 Mobile.Money.Transfer:.Reshaping.Remittances.and.Bridging.Financial. Inclusion.in.Africa.and.Beyond..............................................................................1 Martin Gachukia, Riara University, Kenya The.chapter.reviews.the.growth.of.mobile.money.transactions.(MMTs).and.their. effect.on.international.remittances.and.financial.inclusion..The.novelty.of.MMTs.is. its.widening.adaptation.beyond.Sub-Saharan.Africa.with.increased.confidence.in.use. of.MMTs.by.international.humanitarian.agencies.and.governments.in.reaching.out. to.citizenry.through.government-to-people.(G2P).as.well.as.people-to-government. (P2G).payment.platforms..The.chapter.is.conceptualized.on.the.emergent.themes. emanating.from.the.World.Bank.data.under.the.G20.financial.inclusion.indicators. in. 60. countries. with. remarkable. MMTs. per. 100,000. adults.. Emergent. findings. from.the.data.indicates.of.MMT.benefits.to.small.countries.such.as.the.Pacific. Island.countries,.benign.economic.policies.under.West.African.countries,.increased. uptake.of.cash.and.voucher.transfers.through.humanitarian.support,.and.the.pursuit. of.cashless.economy.through.mobile.wallets..In.essence,.the.growth.of.MMTs.is. -

Mid Year Report 2019 2 Pro Bono & Csr Mid Year Report 2019

MID YEAR REPORT 2019 2 PRO BONO & CSR MID YEAR REPORT 2019 Patron, CSR Committee At A&K we pride ourselves in our culture of giving back. We encourage our staff to not only give but to actively participate in the projects that we support. As a result we continue to see the impact that our efforts are making on people’s lives. I am particularly proud to highlight the Firm’s contribution towards the putting up of an exclusive Managing law library at Strathmore University, which was officially opened on 27th June this year. The Anjarwalla & Khanna Law Library is a marker of our commitment to use our resources to further the Partner’s remarks rule of law and enhance access to legal education. I would especially like to thank the A&K Partners for this contribution. Overall, we are happy to have been instrumental “From everyone who has been given much, much in bringing change to the lives of many through will be demanded; and from the one who has been our CSR efforts in the first half of 2019. We are entrusted with much, much more will be asked.” committed to continue to do more. My deep {Luke 12:48 (NIV)} gratitude goes to the members of the CSR At Anjarwalla & Khanna, we take a broad view of Committee for their exemplary work and to the our obligations to our country, continent and the staff members who have participated in each of the world at large, and as such we see ourselves as initiatives. being expected to give back in a great way.