Influence of Parenting Styles on Adolescents Life-Skills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bertha Kaimenyi.Pdf

Daystar University Staff Profile Template 1. Name: Dr. Bertha Kaimenyi Doctor of Education Senior Lecturer 2. Passport photo: Passport photo here 3. Job Title and Responsibilities: Senior Lecturer School of Communication Teaching General Communication Courses and Leadership Supervising Thesis Mentoring Students Social Welfare Coordinator 4. Biography I have been a senior lecturer in General Communication Courses and Leadership and the following areas: Consultant on Leadership Management Mentoring, Coughing and Role Modeling. Facilitated trainings at KIA and other organizations. Community Involvement Served as Board Member at Kathera Girls High School Served as PTA Chairperson at Precious Blood Secondary school, RIRUTA Consultant on Balanced Lifestyle Motivational Speaker in Work-life balance, Wellness and Staff productivity, KPLC, ICPAK, Standard Chatered, Safaricom. Helping people to be productive and Discover Wellness. Facilitated trainings at British American, Eagle Africa, NSSF. Currently serving as a Director at Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA) Currently serving as a Board Member in the Meru County Council Board Member at Garissa University 5. Academic 1991 Doctor of Education, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI Qualifications: Dissertation Topic - " Issues and problems that face women Pursuing carers in Educational Administration ". Cognate in Communication. 1989 Education Specialist, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, 49104 U.S.A. 1988 Master of Arts in Educational Administration, Andrews University, Berrien Springs MIGHT 49104 U.S.A. 1985 Bachelor of Business Administration (Management), University of Eastern Africa, Eldoret, Kenya. 6. Research Interests: Holistic Education in the area of Balanced Education and Entrepreneurship 7. Publications: Book KAIMENYI B.E (2018). Growing Green Gold. Published by Big Books LTD. Nairobi, Kenya. Book Chapter KAIMENYI B.E. -

Daystar University Staff Profile for Brenda M. Wambua

Daystar University Staff Profile For Brenda M. Wambua 1. Name: Brenda Mueni Wambua Lecturer, English and Linguistics 2. Passport photo: 3. Job Title and Responsibilities: Ms. Brenda Mueni Wambua Assistant Lecturer Language and Performing Arts, School of Communication. Teaching English (General Education Courses) and Linguistics Coordinator, Writing and Speech Centre Mentoring Students 4. Biography (About Me): I have been a teacher of English and Literature in various secondary schools: Kithangaini Secondary school (Machakos), Bishop Ngala Secondary School (Makueni) and Pangani Girls School (Nairobi). In one of the schools, Bishop Ngala Secondary School, I was a Deputy Principal. I have taught on part time basis in various universities as well: Pan African Christian University, Nazarene University, Machakos University, Kenyatta University and United States International University. I worked as an examiner as well as a Senior Examiner for Kenya National Examination Council. I am a lecturer in the Departments of Language and Performing Arts, School of Communication. I teach English and Linguistics. I also coordinate the Writing and speech Centre. I am the one in charge of time tabling classes for our department after the Head of Department has projected the classes. I train peer tutors and organize both Public Speaking and Writing competitions through the Writing and Speech Centre. I supervise Masters thesis as well. I am a trained Editor and so I edit Masters thesis and articles for Daystar Connect. I am Ph.D student at Machakos University and I have done research in various fields such as Language Planning and Policy, Academic Writing and Second Language Acquisition and Learning. -

Of Selected Standard Seven Pupils in Six Primary Schools in Lang‟Ata Constituency, Nairobi County

Daystar University Repository Effects Of Communication Involved In Play In Developing Interpersonal Skills: A Case Of Selected Standard Seven Pupils In Six Primary Schools In Lang‟Ata Constituency, Nairobi County by Redempta Oburu 11-1111 A thesis presented to the School of Communication, Language and Performing Arts of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Communication July 2017 Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository APPROVAL EFFECTS OF COMMUNICATION INVOLVED IN PLAY IN DEVELOPING INTERPERSONAL SKILLS: A CASE OF SELECTED STANDARD SEVEN PUPILS IN SIX PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN LANG‟ATA CONSTITUENCY, NAIROBI COUNTY. by Redempta Oburu 11-1111 In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the Master of Arts degree. Date: _____________________________ ____________________ Rebecca Oladipo, PhD, 1st Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Leah Komen, PhD, 2nd Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Rosemary Kowour, PhD, HOD, Communication Department _____________________________ ____________________ Levi Obonyo, PhD, Dean, School of Communication, Language and Performing Arts ii Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository Copyright ©2017 Redempta Oburu iii Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository DECLARATION EFFECTS OF COMMUNICATION INVOLVED IN PLAY IN DEVELOPING INTERPERSONAL SKILLS: A CASE OF SELECTED STANDARD SEVEN PUPILS IN SIX PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN LANG‟ATA CONSTITUENCY, NAIROBI COUNTY. I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit. Signed: ____________________________ Date: ________________ Redempta Oburu (11-1111) iv Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to specially acknowledge and thank my supervisors, Prof. -

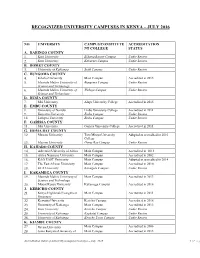

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

Examining the Relationship Between Exclusive Breastfeeding and a Mother’S Mental Health: a Case of Professional Working Mothers in Safaricom Limited, Nairobi, Kenya

DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING AND A MOTHER’S MENTAL HEALTH: A CASE OF PROFESSIONAL WORKING MOTHERS IN SAFARICOM LIMITED, NAIROBI, KENYA by Catherine Kiromo A thesis presented to the School of Human and Social Sciences of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Counselling Psychology October 2020 LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY APPROVAL EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING AND A MOTHER’S MENTAL HEALTH: A CASE OF WORKING MOTHERS IN SAFARICOM LIMITED, NAIROBI, KENYA by Catherine Kiromo 16-1896 In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the Master of Arts degree. Date: _____________________________ ___________________ Jared Menecha, PhD, 1st Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Stephen Ndegwa, PhD, 2nd Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Susan Muriungi, PhD, HOD, Psychology and Counselling _____________________________ ____________________ Kennedy Ongaro, PhD, Dean, School of Human and Social Science ii LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY Copyright © 2020 Catherine Kiromo iii LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY DECLARATION EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING AND A MOTHER’S MENTAL HEALTH: A CASE OF WORKING MOTHERS IN SAFARICOM LIMITED, NAIROBI, KENYA I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit Signed: _________________________ Date: _____________________ Catherine Kiromo 16-1896 LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I give thanks to the Almighty God for His love, care, and good health that He has granted me throughout my life, especially during this thesis journey. -

Influence of Media Training on the Competence of Journalists in Kenya

Influence of Media Training on the Competence of Journalists in Kenya: Perceptions of Standard Group Limited Managers and Senior Journalists Amukuzi, Marion1, Kuria, Githinji Martin2 Riara University, Kenya1, Karatina University, Kenya2 Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract A number of researches have indicated that training institutions have failed to impart skills and knowledge to students that would be transferred to the industry upon graduation and employment, hence the quality of journalists graduating is wanting. The purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of media training on the competency of journalists in Kenya. Curricula were sampled from selected Kenyan universities and adequacy of training material investigated. Non-probability sampling procedure involving purposive and snow-ball sampling methods were used to identify the 9 participants comprising media managers and senior journalists in one media organization. Data was analysed thematically and presented in a narrative form in accordance with the themes. According to the SG media managers and senior journalists, journalists trained in Kenya lack practical skills required in the job market. Consequently, media houses are recruiting graduates in other disciplines such as English, Medicine, and Law while others have resorted to re-training the new recruits. It is recommended that media training institutions, regulators and other stakeholders should revamp existing curricula with the view to making them competency based. Keyword: Influence of Media, Journalists, Perceptions Standard Group Limited, Managers and Senior Journalists. Introduction and Background of the Study The performance of media in Kenya is closely related to the level of journalism training where appropriate training provides students with knowledge and skills to write accurate, fair, balanced and impartial stories (Mbeke, 2010). -

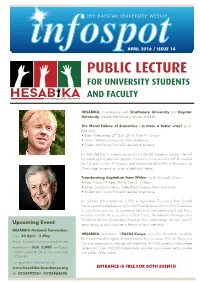

Public Lecture for University Students and Faculty

THE DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY WEEKLY APRIL 2016 / ISSUE 14 PUBLIC LECTURE FOR UNIVERSITY STUDENTS AND FACULTY HESABIKA, in partnership with Strathmore University and Daystar University, presents the following lectures and talks; The Moral Failure of Economics – Is there a better way? by Dr Paul Mills. • Date: Wednesday, 27 April, 2016. Time 9 - 12 noon • Venue: Strathmore University, Main Auditorium • Student and Faculty Picture ID required at entrance. Dr. Mills (left top) is a senior economist for the IMF based in London. He will be speaking in a personal capacity. Previous to his work in the IMF he worked for 13 years in the UK Treasury, and before that did a PhD in Economics at Cambridge University on issues of debt and interest. Transforming Capitalism from Within, by Dr. Michael Schluter. • Date: Friday, 29 April, 2016. Time 3 - 4.30pm • Venue: Daystar University, Valley Road Campus, Main Auditorium • Student and Faculty Picture ID required at entrance Dr. Schluter (left bottom) has a PhD in Agricultural Economics from Cornell University and worked previously for the World Bank as an Economics Consultant in East Africa and also as a research Fellow for the international Food Policy Research Institute. He is co-author of The R Factor, The Relational Manager, and The Relational Lens (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming). He also spent 5 Upcoming Event years setting up rural industries in Kenya in the private sector. HESABIKA National Convention, HESABIKA, an initiative of FOCUS Kenya, is a call to Kenyans to Stand Up Date: 30 April - 2 May Be Counted and be agents of transformation for our nation. -

The Kenyan Social Media Landscape: Trends and Emerging Narratives, 2020 B.Sc

The Kenyan Social Media Landscape: Trends and Emerging Narratives, 2020 B.Sc. Global Leadership and Governance M.Sc. Information Security The Kenyan Social Media Landscape: Trends and Emerging Narratives, 2020 Paul Watzlavick The Counselor for Public Affairs, U.S. Embassy, Nairobi “The United States is proud to support SIMELab and their groundbreaking research into Kenyan social media. The future is digital, so that’s where we need to be: generating innovative solutions to global challenges together.” International Symposium on Social Media USIU-Africa, Nairobi / September 11-12, 2019 “Use of digital media and social media are connected to deep-rooting changes of citizens’ self-concepts” Prof. Dr. Martin Emmer (FU Berlin) (From Left to Right) Dr. Geoffrey Sikolia, Mr. Robert Alai, Ms. Juliet Kanjukia, Ms. Ivy Mungai and Mr. Dennis Itumbi in a panel discussion on “Social Media and Governance” during the 2019 International Symposium on Social Media (From Left to Right) Mr. Alex Taremwa, Ms. Noella Musundi, Mr. David Gitari, Ms. Lucy Wamuyu and Martin Muli in a panel discussion on “Social Media versus Mainstream Media” during the 2019 International Symposium In this report Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................................10 Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................12 Key Discoveries in 2020 ...........................................................................................................................14 -

An Audit of the Kenya Slum Upgrading Programme Communication Strategy

Daystar University Repository Integrating Participatory Communication into Slum Upgrading In Kibera: An Audit of the Kenya Slum Upgrading Programme Communication Strategy by Lilian Jerotich Kimeto 07-0528 A thesis presented to the School of Communication & Languages of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Communication. February 2016 Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository INTEGRATING PARTICIPATORY COMMUNICATION INTO SLUM UPGRADING IN KIBERA: AN AUDIT OF THE KENYA SLUM UPGRADING PROGRAMME COMMUNICATION STRATEGY by Lilian Jerotich Kimeto 07-0528 In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the Master of Arts degree _____________________________ ____________________ Levi Obonyo, PhD, 1st Supervisor ______________________________ ____________________ Clayton Peel, PhD, 2nd Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Rosemary Kowuor, PhD, HoD, Communication Department _____________________________ ____________________ Levi Obonyo, PhD Dean, School of Communication & Languages Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository DECLARATION INTEGRATING PARTICIPATORY COMMUNICATION INTO SLUM UPGRADING IN KIBERA: AN AUDIT OF THE KENYA SLUM UPGRADING PROGRAMME COMMUNICATION STRATEGY I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit. Date: Signed: ____________________________ ____________________ Lilian Jerotich Kimeto (07-0528) Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have no words to express my thanksgiving to God the Almighty who has helped me complete this research. I was unwell for most of this period but God has kept me alive. I am eternally grateful to my dad, Julius Kimeto Bartilol Arap Rutto, who prayed for and encouraged me in this undertaking despite being also unwell. -

AFRO-BIBLICAL HERMENEUTICS in AFRICA TODAY by Julius Gathogo1 and John Kennedy Kinyua2

An article published by Churchman Journal, UK, Volume 131 (2), (2010): pages 251-265 AFRO-BIBLICAL HERMENEUTICS IN AFRICA TODAY By Julius Gathogo1 and John Kennedy Kinyua2 Abstract By Afro-biblical hermeneutics, we mean biblical interpretations done in Africa especially by African instituted Churches. These hermeneutical works are typically African in character in the sense that they consciously or unconsciously borrow heavily from African religious heritage, in their dialogue with the gospel of Christ. The paper sets out to demonstrate that the Biblical hermeneutics in Kenya and Africa at large was largely shaped and/or inspired by biblical translation. That is upon the Bible being translated into the local/indigenous languages, Africans began to re-interpret it in their „relevant fashions, a phenomenon which contrasted the missionary approaches. Second, biblical translations also gave rise to the birth of African independent/instituted Churches, whose hermeneutical standpoints largely speaks for the entire „Biblical hermeneutics in Africa today.‟ Introduction The Dictionary of Biblical Interpretation defines hermeneutics as a theory of interpretation or the art of understanding any written text.3 According to Zablon Nthamburi and Douglas Waruta, the word hermeneutics is derived from a Greek word meaning „interpretation,‟ „translation‟ or „explanation.‟4 Therefore, biblical hermeneutics is the art or technique of interpreting the biblical text in order to understand its original context and then find its contemporary meaning. Nthamburi -

Science in Kenya

SCIENCE IN KENYA Scientific institutions in Kenya include the UNESCO Regional Office for Science and Technology for Africa, in Nairobi; coffee and tea research foundations; grasslands and plant-breeding research stations; and numerous centers for medical, agricultural, and veterinary research. Medical research focuses on the study of leprosy and tuberculosis. The National Council for Science and Technology advises the government on scientific matters, and the Kenya National Academy of Sciences promotes advancement of learning and research; both organizations were founded in Nairobi in 1977. The University of Nairobi, founded in 1956, has colleges of agriculture and veterinary sciences, health sciences, architecture and engineering, and biological and physical sciences. Kenyatta University, founded in 1939 at Nairobi, has faculties of science and environmental education. Moi University, founded in 1984 in Eldoret, has faculties of forest resources and wildlife administration, science, technology, information sciences, environmental studies, health sciences, and agriculture. Edgerton University, founded in 1939 at Njoro, has faculties of agriculture and science. Other higher-education institutions include Jomo Kenyatta University College of Agriculture and Technology, Kenya Medical Training College, and Kenya Polytechnic, all in Nairobi, and five other institutes of science and technology elsewhere in the country. In 1987–97, science and engineering students accounted for 19% of college and university enrollments. scientific institutions -

Factors Affecting Motivation of Presbyterian Church of East Africa Church Evangelists in Nairobi Region, Kenya

Daystar University Repository Factors Affecting Motivation of Presbyterian Church of East Africa Church Evangelists In Nairobi Region, Kenya by Jane Wambui Njoroge A thesis presented to the School of Business and Economics of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION in Human Resource Management May 2014 Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository FACTORS AFFECTING MOTIVATION OF P.C.E.A CHURCH EVANGELISTS IN NAIROBI REGION, KENYA by Jane Wambui Njoroge In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Business Administration degree Date ______________________________ _____________________ Kyongo Joanes, MBA, 1st Supervisor _______________________________ _______________________ Dulo Charles, MBA, 2nd Supervisor _______________________________ _______________________ Thomas Koyier, Msc, HOD, Commerce Department ___________________________________ ________________________ Evans Amata, MFC, Dean, School of Business and Economics. ii Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository DECLARATION FACTORS AFFECTING MOTIVATION OF PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH OF EAST AFRICA CHURCH EVANGELISTS IN NAIROBI REGION, KENYA I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit. Signed: ____________________________ Date ____________________ Jane Wambui Njoroge (09-0561) iii Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge first and fore most the almighty God for his strength that has enabled me to accomplish this exercise. It was not easy but by the grace of God I am able to be where I am. Thanks to Daystar US scholarship that provided the needed finances when I thought I had come to my end. As for Jennifer Kinoti, God knows your efforts and will keep his word to bless you.