Mageto Ethics Conference Paper 2010 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bertha Kaimenyi.Pdf

Daystar University Staff Profile Template 1. Name: Dr. Bertha Kaimenyi Doctor of Education Senior Lecturer 2. Passport photo: Passport photo here 3. Job Title and Responsibilities: Senior Lecturer School of Communication Teaching General Communication Courses and Leadership Supervising Thesis Mentoring Students Social Welfare Coordinator 4. Biography I have been a senior lecturer in General Communication Courses and Leadership and the following areas: Consultant on Leadership Management Mentoring, Coughing and Role Modeling. Facilitated trainings at KIA and other organizations. Community Involvement Served as Board Member at Kathera Girls High School Served as PTA Chairperson at Precious Blood Secondary school, RIRUTA Consultant on Balanced Lifestyle Motivational Speaker in Work-life balance, Wellness and Staff productivity, KPLC, ICPAK, Standard Chatered, Safaricom. Helping people to be productive and Discover Wellness. Facilitated trainings at British American, Eagle Africa, NSSF. Currently serving as a Director at Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA) Currently serving as a Board Member in the Meru County Council Board Member at Garissa University 5. Academic 1991 Doctor of Education, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI Qualifications: Dissertation Topic - " Issues and problems that face women Pursuing carers in Educational Administration ". Cognate in Communication. 1989 Education Specialist, Andrews University, Berrien Springs, 49104 U.S.A. 1988 Master of Arts in Educational Administration, Andrews University, Berrien Springs MIGHT 49104 U.S.A. 1985 Bachelor of Business Administration (Management), University of Eastern Africa, Eldoret, Kenya. 6. Research Interests: Holistic Education in the area of Balanced Education and Entrepreneurship 7. Publications: Book KAIMENYI B.E (2018). Growing Green Gold. Published by Big Books LTD. Nairobi, Kenya. Book Chapter KAIMENYI B.E. -

Influence of Parenting Styles on Adolescents Life-Skills

DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY INFLUENCE OF PARENTING STYLES ON ADOLESCENTS LIFE-SKILLS DEVELOPMENT: A CASE OF ADOLESCENTS ATTENDING TEENS CHURCH IN DELIVERANCE CHURCH INTERNATIONAL UMOJA, NAIROBI COUNTY by Mercy Muthoni Nzuki A thesis presented to the School of Human and Social Sciences of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Counseling Psychology October 2020 LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY APPROVAL INFLUENCE OF PARENTING STYLES ON ADOLESCENTS LIFE-SKILLS DEVELOPMENT: A CASE OF ADOLESCENTS ATTENDING TEENS CHURCH IN DELIVERANCE CHURCH INTERNATIONAL UMOJA, NAIROBI COUNTY by Mercy Muthoni Nzuki In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree. Date: _____________________________ ____________________ Susan Muriungi, PhD, 1st Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Winnie Waiyaki, PhD, 2nd Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Susan Muriungi, PhD, HoD, Counseling Psychology ______________________________ _____________________ Kennedy Ongaro, PhD, Dean, School of Human and Social Sciences ii LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY Copyright © 2020 Mercy Muthoni Nzuki iii LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY DECLARATION INFLUENCE OF PARENTING STYLES ON ADOLESCENTS LIFE-SKILLS DEVELOPMENT: A CASE OF ADOLESCENTS ATTENDING TEENS CHURCH IN DELIVERANCE CHURCH INTERNATIONAL UMOJA, NAIROBI COUNTY I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit. Signed: ______________________ Date: ___________________ Mercy Muthoni Nzuki 16-0493 iv LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My gratitude goes to the almighty God for giving me the strength to complete this study. I thank my supervisors, Dr. Susan Muriungi and Dr. -

Daystar University Staff Profile for Brenda M. Wambua

Daystar University Staff Profile For Brenda M. Wambua 1. Name: Brenda Mueni Wambua Lecturer, English and Linguistics 2. Passport photo: 3. Job Title and Responsibilities: Ms. Brenda Mueni Wambua Assistant Lecturer Language and Performing Arts, School of Communication. Teaching English (General Education Courses) and Linguistics Coordinator, Writing and Speech Centre Mentoring Students 4. Biography (About Me): I have been a teacher of English and Literature in various secondary schools: Kithangaini Secondary school (Machakos), Bishop Ngala Secondary School (Makueni) and Pangani Girls School (Nairobi). In one of the schools, Bishop Ngala Secondary School, I was a Deputy Principal. I have taught on part time basis in various universities as well: Pan African Christian University, Nazarene University, Machakos University, Kenyatta University and United States International University. I worked as an examiner as well as a Senior Examiner for Kenya National Examination Council. I am a lecturer in the Departments of Language and Performing Arts, School of Communication. I teach English and Linguistics. I also coordinate the Writing and speech Centre. I am the one in charge of time tabling classes for our department after the Head of Department has projected the classes. I train peer tutors and organize both Public Speaking and Writing competitions through the Writing and Speech Centre. I supervise Masters thesis as well. I am a trained Editor and so I edit Masters thesis and articles for Daystar Connect. I am Ph.D student at Machakos University and I have done research in various fields such as Language Planning and Policy, Academic Writing and Second Language Acquisition and Learning. -

Of Selected Standard Seven Pupils in Six Primary Schools in Lang‟Ata Constituency, Nairobi County

Daystar University Repository Effects Of Communication Involved In Play In Developing Interpersonal Skills: A Case Of Selected Standard Seven Pupils In Six Primary Schools In Lang‟Ata Constituency, Nairobi County by Redempta Oburu 11-1111 A thesis presented to the School of Communication, Language and Performing Arts of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Communication July 2017 Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository APPROVAL EFFECTS OF COMMUNICATION INVOLVED IN PLAY IN DEVELOPING INTERPERSONAL SKILLS: A CASE OF SELECTED STANDARD SEVEN PUPILS IN SIX PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN LANG‟ATA CONSTITUENCY, NAIROBI COUNTY. by Redempta Oburu 11-1111 In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the Master of Arts degree. Date: _____________________________ ____________________ Rebecca Oladipo, PhD, 1st Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Leah Komen, PhD, 2nd Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Rosemary Kowour, PhD, HOD, Communication Department _____________________________ ____________________ Levi Obonyo, PhD, Dean, School of Communication, Language and Performing Arts ii Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository Copyright ©2017 Redempta Oburu iii Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository DECLARATION EFFECTS OF COMMUNICATION INVOLVED IN PLAY IN DEVELOPING INTERPERSONAL SKILLS: A CASE OF SELECTED STANDARD SEVEN PUPILS IN SIX PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN LANG‟ATA CONSTITUENCY, NAIROBI COUNTY. I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit. Signed: ____________________________ Date: ________________ Redempta Oburu (11-1111) iv Library Archives Copy Daystar University Repository ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to specially acknowledge and thank my supervisors, Prof. -

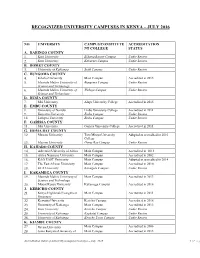

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

Digital Skills in Sub-Saharan Africa Spotlight on Ghana

Digital Skills in Sub-Saharan Africa Spotlight on Ghana IN COOPERATION WITH: ABOUT IFC Research and writing underpinning the report was conducted by the L.E.K. Global Education practice. The L.E.K. IFC—a sister organization of the World Bank and member of team was led by Ashwin Assomull, Maryanna Abdo, and the World Bank Group—is the largest global development Ridhi Gupta, including writing by Maryanna Abdo, Priyanka institution focused on the private sector in emerging Thapar, and Jaisal Kapoor and research contributions by Neil markets. We work with more than 2,000 businesses Aneja, Shrrinesh Balasubramanian, Patrick Desmond, Ridhi worldwide, using our capital, expertise, and influence to Gupta, Jaisal Kapoor, Rohan Sur, and Priyanka Thapar. create markets and opportunities in the toughest areas of Sudeep Laad provided valuable insights on the Ghana the world. For more information, visit www.ifc.org. market landscape and opportunity sizing. ABOUT REPORT L.E.K. is a global management consulting firm that uses deep industry expertise and rigorous analysis to help business This publication, Digital Skills in Sub-Saharan Africa: Spotlight leaders achieve practical results with real impact. The Global on Ghana, was produced by the Manufacturing Agribusiness Education practice is a specialist international team based in and Services department of the International Finance Singapore serving a global client base from China to Chile. Corporation, in cooperation with the Global Education practice at L.E.K. Consulting. It was developed under the ACKNOWLEDGMENTS overall guidance of Tomasz Telma (Senior Director, MAS), The report would not have been possible without the Mary-Jean Moyo (Director, MAS, Middle-East and Africa), participation of leadership and alumni from eight case study Elena Sterlin (Senior Manager, Global Health and Education, organizations, including: MAS) and Olaf Schmidt (Manager, Services, MAS, Sub- Andela: Lara Kok, Executive Coordinator; Anudip: Dipak Saharan Africa). -

Education Quarterly Reviews

Education Quarterly Reviews Siluyele, Nimrod, Nkonde, Edward, Mweemba, Malawo, Kaluba, Goodhope, and Zulu, Cleopas. (2020), A Survey on Student Preferences of Facilities and Models of Accommodation at Kapasa Makasa University, Zambia. In: Education Quarterly Reviews, Vol.3, No.2, 261-270. ISSN 2621-5799 DOI: 10.31014/aior.1993.03.02.138 The online version of this article can be found at: https://www.asianinstituteofresearch.org/ Published by: The Asian Institute of ResearcH The Education Quarterly Reviews is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied, and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. The Asian Institute of ResearcH Education Quarterly Reviews is a peer-reviewed International Journal. THe journal covers scholarly articles in the fields of education, linguistics, literature, educational theory, research, and metHodologies, curriculum, elementary and secondary education, HigHer education, foreign language education, teacHing and learning, teacHer education, education of special groups, and other fields of study related to education. As tHe journal is Open Access, it ensures HigH visibility and tHe increase of citations for all researcH articles published. The Education Quarterly Reviews aims to facilitate scholarly work on recent theoretical and practical aspects of education. The Asian Institute of ResearcH Education Quarterly Reviews Vol.3, No.2, 2020: 261-270 ISSN 2621-5799 CopyrigHt © The AutHor(s). All RigHts Reserved DOI: 10.31014/aior.1993.03.02.138 -

Examining the Relationship Between Exclusive Breastfeeding and a Mother’S Mental Health: a Case of Professional Working Mothers in Safaricom Limited, Nairobi, Kenya

DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING AND A MOTHER’S MENTAL HEALTH: A CASE OF PROFESSIONAL WORKING MOTHERS IN SAFARICOM LIMITED, NAIROBI, KENYA by Catherine Kiromo A thesis presented to the School of Human and Social Sciences of Daystar University Nairobi, Kenya In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Counselling Psychology October 2020 LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY APPROVAL EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING AND A MOTHER’S MENTAL HEALTH: A CASE OF WORKING MOTHERS IN SAFARICOM LIMITED, NAIROBI, KENYA by Catherine Kiromo 16-1896 In accordance with Daystar University policies, this thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the Master of Arts degree. Date: _____________________________ ___________________ Jared Menecha, PhD, 1st Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Stephen Ndegwa, PhD, 2nd Supervisor _____________________________ ____________________ Susan Muriungi, PhD, HOD, Psychology and Counselling _____________________________ ____________________ Kennedy Ongaro, PhD, Dean, School of Human and Social Science ii LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY Copyright © 2020 Catherine Kiromo iii LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY DECLARATION EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING AND A MOTHER’S MENTAL HEALTH: A CASE OF WORKING MOTHERS IN SAFARICOM LIMITED, NAIROBI, KENYA I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college or university for academic credit Signed: _________________________ Date: _____________________ Catherine Kiromo 16-1896 LIBRARY ARCHIVES COPY DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY REPOSITORY ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I give thanks to the Almighty God for His love, care, and good health that He has granted me throughout my life, especially during this thesis journey. -

Influence of Media Training on the Competence of Journalists in Kenya

Influence of Media Training on the Competence of Journalists in Kenya: Perceptions of Standard Group Limited Managers and Senior Journalists Amukuzi, Marion1, Kuria, Githinji Martin2 Riara University, Kenya1, Karatina University, Kenya2 Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract A number of researches have indicated that training institutions have failed to impart skills and knowledge to students that would be transferred to the industry upon graduation and employment, hence the quality of journalists graduating is wanting. The purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of media training on the competency of journalists in Kenya. Curricula were sampled from selected Kenyan universities and adequacy of training material investigated. Non-probability sampling procedure involving purposive and snow-ball sampling methods were used to identify the 9 participants comprising media managers and senior journalists in one media organization. Data was analysed thematically and presented in a narrative form in accordance with the themes. According to the SG media managers and senior journalists, journalists trained in Kenya lack practical skills required in the job market. Consequently, media houses are recruiting graduates in other disciplines such as English, Medicine, and Law while others have resorted to re-training the new recruits. It is recommended that media training institutions, regulators and other stakeholders should revamp existing curricula with the view to making them competency based. Keyword: Influence of Media, Journalists, Perceptions Standard Group Limited, Managers and Senior Journalists. Introduction and Background of the Study The performance of media in Kenya is closely related to the level of journalism training where appropriate training provides students with knowledge and skills to write accurate, fair, balanced and impartial stories (Mbeke, 2010). -

Re-Fashioning African Studies in an Information Technology Driven World for Africa’S Transformation Joseph Octavius Akolgo

Contemporary Journal of African Studies 2019; 6 (1): 114-137 https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/contjas.v6i1.7 ISSN 2343-6530 © 2019 The Author(s) Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Re-fashioning African Studies in an information technology driven world for Africa’s transformation Joseph Octavius Akolgo Phd Candidate, Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana Author’s email: [email protected] Abstract The African Studies programme, launched in the University of Ghana by Ghana’s first president, was for “students to know and understand their roots, inherited past traditions, norms and lore (and to) re-define the African personality” and the “inculcation of time honoured African values of truthfulness, humanness, rectitude and honour …and ultimately ensure a more just and orderly African society” Sackey (2014:225). These and other principles constitute some of the cardinal goals of the programme in both public and private universities in Ghana. Considering tertiary education as both a public and private enterprise, this paper seeks to enrich the discourse on African Studies by taking a retrospection of the subject and investigated university students’ perceptions of the discipline among public and privately funded spheres. Adopting a qualitative approach, the paper interviewed students on the relevance of the discipline in a contemporary information technology driven world. The outcome of such interrogation was that African Studies is even more relevant in the era of globalization than it might have been in immediate post independent Africa. -

Challenges for Open and Distance Learning (ODL) Students: Experiences from Students of the Zimbabwe Open University

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.6, No.18, 2015 Challenges for Open and Distance learning (ODL) Students: Experiences from Students of the Zimbabwe Open University Maxwell C.C. Musingafi 1* Barbra Mapuranga 2 Kudzai Chiwanza 3 Shupikai Zebron 4 1. Zimbabwe Open University, Development Studies, Masvingo Regional Campus 2. Zimbabwe Open University, Disability Studies, Mashonaland East 3. .Zimbabwe Open University, Library and Information Sciences, Harare 4. Zimbabwe Open University, Counselling, Mashonaland West Regional Campus Abstract The purpose of this study was to investigate the challenges facing Open and Distance Learning students at the Zimbabwe Open University (ZOU). The study was conducted at ZOU Masvingo Regional Campus. The study employed both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The main data collection techniques were questionnaires and structured interviews, supplemented by documentary review. Tables, frequencies and percentages were the key descriptive statistics used to analyze and present the findings. The results showed that ODL learners were challenged with a range of obstacles in their course of studies. The most reported challenges were lack of sufficient time for study, difficulties in access and use of ICT, ineffective feedback and lack of study materials. It was recommended that ZOU should strive to achieve effective and balanced teaching and learning system that satisfies the desire of the learners to the extent that they would wish to come back to the institution for further studies and feel proud to recommend the institution to others who are seeking for knowledge. Key words: challenges, ODL, students, ZOU, drop-out rate, late programme completion, ICT, Masvingo. -

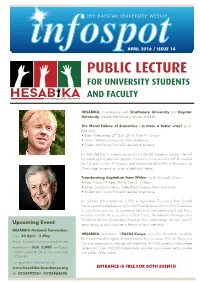

Public Lecture for University Students and Faculty

THE DAYSTAR UNIVERSITY WEEKLY APRIL 2016 / ISSUE 14 PUBLIC LECTURE FOR UNIVERSITY STUDENTS AND FACULTY HESABIKA, in partnership with Strathmore University and Daystar University, presents the following lectures and talks; The Moral Failure of Economics – Is there a better way? by Dr Paul Mills. • Date: Wednesday, 27 April, 2016. Time 9 - 12 noon • Venue: Strathmore University, Main Auditorium • Student and Faculty Picture ID required at entrance. Dr. Mills (left top) is a senior economist for the IMF based in London. He will be speaking in a personal capacity. Previous to his work in the IMF he worked for 13 years in the UK Treasury, and before that did a PhD in Economics at Cambridge University on issues of debt and interest. Transforming Capitalism from Within, by Dr. Michael Schluter. • Date: Friday, 29 April, 2016. Time 3 - 4.30pm • Venue: Daystar University, Valley Road Campus, Main Auditorium • Student and Faculty Picture ID required at entrance Dr. Schluter (left bottom) has a PhD in Agricultural Economics from Cornell University and worked previously for the World Bank as an Economics Consultant in East Africa and also as a research Fellow for the international Food Policy Research Institute. He is co-author of The R Factor, The Relational Manager, and The Relational Lens (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming). He also spent 5 Upcoming Event years setting up rural industries in Kenya in the private sector. HESABIKA National Convention, HESABIKA, an initiative of FOCUS Kenya, is a call to Kenyans to Stand Up Date: 30 April - 2 May Be Counted and be agents of transformation for our nation.