Autobiographical Elements in David Musila's Seasons of Hope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliament of Kenya the Senate

February 4, 2014 SENATE DEBATES 1 PARLIAMENT OF KENYA THE SENATE THE HANSARD Tuesday, 4th February, 2014 Special Sitting (Convened via Kenya Gazette Notice No.627 of 31st January, 2014) The Senate met at County Hall, Parliament Buildings, at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro) in the Chair] PRAYERS QUORUM CALL AT COMMENCEMENT OF SITTING The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro): Order, hon. Senators. We need to determine if we have a quorum. The Clerk of the Senate (Mr. Nyegenye): Mr. Speaker, Sir, we have 32 hon. Senators in the House. We have a quorum. The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro): In that case, let us proceed. ADMINISTRATION OF OATH (The Senator-Elect for Bungoma County entered the Chamber escorted by Sen. Musila and Sen. (Dr.) Khalwale) Sen. (Dr.) Khalwale: Mr. Speaker, Sir, it is my pleasure and privilege, on behalf of the people of Bungoma County, to introduce Moses Masika Wetangula as the Senator- Elect for Bungoma County. (Applause) The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro): Welcome, Senator. He may now proceed to take the oath. The Oath of Allegiance was administered to the following Senator:- Disclaimer: The electronic version of the Senate Hansard Report is for information purposes only. A certified version of this Report can be obtained from the Hansard Editor, Senate. February 4, 2014 SENATE DEBATES 2 Sen. Wetangula Moses Masika. (Applause) The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro): Order, Sen. Wetangula. You have to go back to the bar and come and do that after. (Sen. Wetangula approached the bar) (Applause) The Speaker (Hon. Ethuro): Next order. COMMUNICATION FROM THE CHAIR JUSTIFICATION FOR SPECIAL SITTING AND PROCEDURE OF DEBATE OF MOTION TO ESTABLISH A SPECIAL COMMITTEE The Speaker (Hon. -

Report of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION The Government should immediately carry out counselling services, especially to those who lost their entire families to avoid mental breakdown. It is not too late to counsel the victims because they have not undergone any counselling at all. The community also seeks an apology from the Government, the reason being that the Government was supposed to protect its citizens yet it allowed its security forces to violently attack them and, therefore, perpetrated gross violation of their rights. Anybody who has been My recommendation to this Government is that it should involved in the killing address the question of equality in this country. We do of Kenyans, no matter not want to feel as if we do not belong to this country. We what position he holds, demand to be treated the same just like any other Kenyan in should not be given any any part of this country. We demand for equal treatment. responsibility. Volume IV KENYA REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION Volume IV © Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission, 2013 This publication is available as a pdf on the website of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (and upon its dissolution, on the website of its successor in law). It may be copied and distributed, in its entirety, as long as it is attributed to the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission and used for noncommercial educational or public policy purposes. Photographs may not be used separately from the publication. Published by Truth Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC), Kenya ISBN: 978-9966-1730-3-4 Design & Layout by Noel Creative Media Limited, Nairobi, Kenya His Excellency President of the Republic of Kenya Nairobi 3 May 2013 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL By Gazette Notice No. -

Parliament of Kenya the Senate

September 19, 2013 SENATE DEBATES 1 PARLIAMENT OF KENYA THE SENATE THE HANSARD Thursday, 19th September, 2013 The Senate met at the Kenyatta International Conference Centre at 2.30 p.m. [The Temporary Speaker (Sen. Murkomen) in the Chair] PRAYERS QUORUM CALL AT COMMENCEMENT OF SITTING The Temporary Speaker (Sen. Murkomen): Hon. Senators, we have a quorum. Let us proceed with today’s business. PAPERS LAID REPORTS OF THE FINANCE COMMITTEE ON COUNTY ESTIMATES/CASH DISBURSEMENT SCHEDULE Sen. Billow: Mr. Temporary Speaker, Sir, I beg to lay the following Papers on the Table of the House, today, Thursday, 19th September, 2013:- Report of the Finance Committee on the Investigations on Irregular Alteration to the Budget Estimates for Turkana County for the Fiscal Year 2013/2014. Report of the Finance Committee on the Cash Disbursement Schedule for County Governments for the Fiscal Year 2013/2014. NOTICES OF MOTIONS Sen. Billow: Mr. Temporary Speaker, Sir, I beg to give notice of the following Motions:- ADOPTION OF REPORT ON COUNTY GOVERNMENT CASH DISBURSEMENT SCHEDULE FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2013/2014 THAT, pursuant to the provisions of sections 17(7) of the Public Finance Management Act, the Senate adopts the Report of the Standing Disclaimer: The electronic version of the Senate Hansard Report is for information purposes only. A certified version of this Report can be obtained from the Hansard Editor, Senate. September 19, 2013 SENATE DEBATES 2 Committee on Finance, Commerce and Economic Affairs on the County Government Cash Disbursement Schedule for the year 2013/2014 ADOPTION OF REPORT ON IRREGULAR ALTERATION OF ESTIMATES FOR TURKANA COUNTY THAT, the Senate adopts the Report of the Standing Committee on Finance, Commerce and Economic Affairs on the Investigations carried out by the Controller of Budget on the Irregular Alteration of the Budget Estimates for Turkana County for the Fiscal Year 2013/2014. -

Chapter 7 Executive Powers, Functions, and Structure In

CHAPTER 7 EXECUTIVE POWERS, FUNCTIONS, AND STRUCTURE IN KENYA AND AFRICA CONCEPTS, THEORY, HISTORY, AND PRACTICE This Chapter may be cited as: Ben Sihanya (forthcoming 2020) “Executive Powers and functions in Kenya and Africa: Concepts, theory and history,” in Ben Sihanya (2020) Constitutional Democracy, Regulatory and Administrative Law in Kenya and Africa Vol. 1: Presidency, Premier, Legislature, Judiciary, Commissions, Devolution, Bureaucracy and Administrative Justice in Kenya, Sihanya Mentoring & Innovative Lawyering, Nairobi & Siaya 7.1 Conceptualising Public, Government and Executive Power in Kenya and Africa1 My overarching argument is that the production, regulation and reproduction of executive power in kenya and Africa has to content with three interrelated theoritical and philosophical question. First, the need to promote popular sovereignity, constitutional democracy and service delivery. Second, avoiding executive fiat and despotism. Third, avoiding anarchy. We review three inter-related constitutional questions on public, government and executive power in Kenya and Africa. First, what are the three sets of public or governmetal powers in Kenya and Africa? Second, what are some of the components of these legislative, executive or administrative, and juridical or adjudicatory powers? Third, how are these powers, related procedures, shared, contested and reproduced horizontally and vertically? What lessons do we learn from Afro-Kenyanist constitutional, legal and political theory of power and the related rights or liberties and processes? How did the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) conceptualize and address public, government and executive power? 7.1.1 The three powers and arms of Government in Kenya and Africa The three sets of powers are legislative, executive and judicial. These are exercised by the Legislature, Executive and Judiciary, respectively. -

Right to Information and Parliamentary Accesibility, Accountability and Transparency

RIGHT TO INFORMATION AND PARLIAMENTARY ACCESIBILITY, ACCOUNTABILITY AND TRANSPARENCY THET KENYAN PARLIAMENT CASE RIGHT TO INFORMATION AND PARLIAMENTARY ACCESSIBILITY, ACCOUNTABILITY & TRANSPARENCY An Analysis of Access to Information, Accountability and Participation in the Kenyan Parliament By Henry Maina & Hillary Onami – Article 19 Eastern Africa Final Technical Report 2011 *IDRC Project No: 106493 * Eastern and Southern Africa Region In collaboration with Article 19 Eastern Africa ACS Plaza2nd Floor, Lenana Road P. O. Box 2653-00100 Nairobi T. +254 20 3862230-2, F. +254 20 3862231 DEFENDING FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND INFORMATION 2 | Right & Access to Information TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................4 Abbreviation and Acronyms................................................................................................................................5 Executive Summary............................................................................................................................................5 1.0 Introduction & Background ................................................................................................................7 1.0 Research Problem……..………………………………………………………………………………11 1.1 Objectives…………...........…………………………………..........................................................12 1.2 Scope of the Study.....................................................................................................................12 -

Newspaper Visibility of Members of Parliament in Kenya*

Journalism and Mass Communication, ISSN 2160-6579 D July 2012, Vol. 2, No. 7, 717-734 DAVID PUBLISHING Newspaper Visibility of Members of Parliament in Kenya* Kioko Ireri Indiana University, Bloomington, USA This research investigates variables that predicted news coverage of 212 members of parliament (MPs) in Kenya by four national newspapers in 2009. The 10 variables examined are: ordinary MP, cabinet minister, powerful ministry, parliamentary committee chairmanship, seniority, big tribe identity, major party affiliation, presidential ambition, commenting on contentious issues, and criticizing government. Findings indicate that commenting on contentious issues, criticizing government, cabinet minister, ordinary MP, powerful ministry, and seniority significantly predicted visibility of the parliamentarians in newspaper news. However, a multiple regression analysis shows that the strongest predictors are commenting on contentious issues, cabinet minister, criticizing government, and big tribe identity. While commenting on controversial issues was the strongest predictor, major party identification and committee leadership were found not to predict MPs’ visibility. Keywords: Kenya, members of parliament (MPs), newspapers, newspaper visibility, politicians, visibility, visibility predictor Introduction Today, the mass media have become important platforms for the interaction of elected representatives and constituents. Through the mass media, citizens learn what their leaders are doing for them and the nation. Similarly, politicians use the media to make their agendas known to people. It is, thus, rare to come across elected leaders ignorant about the importance of registering their views, thoughts, or activities in the news media. In Kenya, members of parliament have not hesitated to exploit the power of the mass media to its fullest in their re-election bids and in other agendas beneficial to them. -

National Constitutional Conference Documents

NATIONAL CONSTITUTIONAL CONFERENCE DOCUMENTS THE REPORT OF THE RAPPORTEUR GENERAL TO THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTIONAL CONFERENCE ON ITS DELIBERATIONS BETWEEN AUGUST 18 – SEPTEMBER 26, 2003 AT THE BOMAS OF KENYA 17TH NOVEMBER, 2003 OUTLINE OF CONTENTS 1. Interruptions in Mortis Causae 2. The Scope of the Report 3. Issues Outstanding at the end of Bomas I 3.1 On devolution of powers 3.2 On Cultural Heritage 3.3 On affirmative action 4. Deliberations of Technical Working Committees 4.1 The Constitution of Technical Working Committees 4.2 The Operation of Technical Working Committees 5. The Roadmap to Bomas III Appendices A. National Constitutional Conference Process B. Membership of Technical Working Committees of the National Constitutional Conference C. Cross-cutting issues with transitional and consequential implications D. List of Individuals or Institutions providing input to Technical Working Committees during Bomas II E. Detailed process in Technical Working Committees F. Template for Interim and final Reports of Committees G. Template for Committee Reports to Steering Committee and Plenary of the Conference 1 THE REPORT OF THE RAPPORTEUR-GENERAL TO THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTIONAL CONFERENCE ON ITS DELIBERATIONS BETWEEN AUGUST 18 – SEPTEMBER 26, 2003 AT THE BOMAS OF KENYA 1. Interruptions in mortis causae 1. Twice during Bomas II, thel Conference was stunned by the sudden and untimely demise of two distinguished delegates, namely: - ° Delegate No.002, the late Hon. Kijana Michael Christopher Wamalwa, MP, Vice-President and Minister for Regional Development, and ° Delegate No. 412,the late Hon. Dr. Chrispine Odhiambo Mbai, Convenor of the Technical Working Committee G on Devolution. 2. Following the demise of the Vice-President in a London Hospital on August 25, 2003, H. -

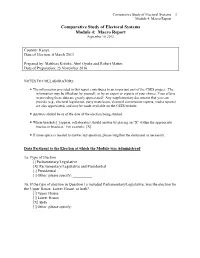

Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 4: Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012 Country: Kenya Date of Election: 4 March 2013 Prepared by: Matthias Krönke, Abel Oyuke and Robert Mattes Date of Preparation: 23 November 2016 NOTES TO COLLABORATORS: . The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] . If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [] Parliamentary/Legislative [X] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [ ] Lower House [X] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __________ Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 4: Macro Report 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election, regardless of whether the election was presidential? Party of National Unity and Allies (National Rainbow Coalition) 2b. -

Republic of Kenya Ministry of Foreign Affairs And

REPUBLIC OF KENYA MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE STRATEGIC PLAN 2018/19 – 2022/23 APRIL 2018 i Foreword The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Trade is mandated to pursue Kenya’s Foreign Policy in accordance with the Constitution of Kenya, with the overarching objective of projecting, promoting and protecting the nation’s interests abroad. Kenya’s Foreign Policy is a tool for pursuing, projecting, promoting and protecting national interests and values across the globe. The underpinning principle of the policy is a strong advocacy for a rule-based international system, environmental sustainability, equitable development and a secure world. This desire and commitment is aptly captured in our vision statement, “A peaceful, prosperous, and globally competitive Kenya” and the mission statement: “To project, promote and protect Kenya’s interests and image globally through innovative diplomacy, and contribute towards a just, peaceful and equitable world”. The overarching goal of this Strategic Plan is to contribute to the country’s development agenda and aspirations under the Kenya Vision 2030, the Third Medium Term Plan and the “Big Four” Agenda on: manufacturing, food and nutrition security, affordable healthcare and affordable housing for Kenyans. We are operating in a period of rapid transition in international relations as exemplified in the unprecedented political and socio-economic dynamism within the global system. A robust and dynamic foreign policy grounded on empirical research and analysis is paramount in addressing the attendant issues presented by globalisation coupled with power shifts towards the newly emerging economies which have redefined the diplomatic landscape. These changing dynamics impose on the Ministry the onerous responsibility of ensuring coherent strategies are developed and deployed to adapt to these global realities while at the same time identifying the corresponding opportunities to enhance Kenya’s global competitiveness in line with the Kenya Vision 2030 and the Third Medium Term Plan. -

The Link Between Poverty and the Right to Free, and Fair Elections in Kenya

THE LINK BETWEEN POVERTY AND THE RIGHT TO FREE, AND FAIR ELECTIONS IN KENYA. UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI MULI STEPHEN MUSILI G62/7564/2017 Research Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws (LLM, Law, Governance and Democracy) OCTOBER 2020 i DECLARATION I, MULI STEPHEN MUSILI do hereby declare that this Research Project is my original work except where indicated by special reference in the text. This Research Project has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a postgraduate degree or any other award in Kenya or elsewhere. Signed…………………………………………… Date……………………………….. Supervisor’s approval Signed ____________________ Date: _______________________ Prof Ben Sihanya, JSD (Stanford) Intellectual Property and Constitutional Professor, Public Interest Advocate and Mentor University of Nairobi Law School and Sihanya Mentoring. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This Research Project was made possible by the guidance and help I received from several individuals whose assistance and contribution should not go unmentioned. To begin with, I thank my supervisor Professor Ben Sihanya for the wisdom, guidance, patience, and continued intellectual support throughout the research process. I feel honored to have worked with such a passionate Professor and a Mentor. Special thanks to my reader Dr. Nkatha Kabira for her guidance and corrections in the final document. I would also wish to pass my heartfelt gratitude to the faculty and staff members at the University Of Nairobi School Of Law for their valuable guidance and help throughout my course work and beyond. Their critique at the departmental and faculty level made this work more appropriate. I would be insincere if I fail to recognize and appreciate the passionate guidance offered to me by Professor Ben Sihanya’s research assistants at Sihanya Mentoring and Innovative Mentoring, Mr. -

07 KEN 2 - 07-12-29 Kisumu

07 KEN 2 - 07-12-29 Kisumu Laboratoiredesfrondeurs.org Segment horizontal du quadrillage ≈ 220 Km. Segment horizontal du quadrillage ≈ 50 km. Largeur du cadre ≈ 44 Km. Carte de Nairobi avec Kibera, Mathare et Huruma http://uk.reuters.com/article/homepageCrisis/idUKL25167897._CH_.242020071225 Opposition holds poll advantage in tight Kenya vote Tue Dec 25, 2007 4:03pm GMT (adds Odinga comments, 5-9) By Andrew Cawthorne NAIROBI, Dec 25 (Reuters) - Two heavyweights of Kenya's post-independence politics square off in a presidential vote on Thursday after a campaign that has overshadowed Christmas and seen the opposition holding a small lead in opinion polls. The closeness of the vote has raised fears that fraud and intimidation may be used to try and swing results in a nation that has enjoyed relative stability and become east Africa's economic power- house since the end of British rule in 1963. All except one of the public surveys since September have put opposition candidate Raila Odinga -- a 62-year-old businessman and former political prisoner -- a few points ahead of President Mwai Kibaki, who won in 2002. Just one recent poll, by Gallup, put Kibaki a point ahead, showing that all is still to play for in an election entertaining Kenyans' minds far more than the festive season. Around the capital Nairobi and other major towns, sparse Christmas decorations were swamped by party colours and vast posters of the main candidates. "This is not likely to be a season of good cheer due to the very human clash of wills between contenders for political power," wrote the Daily Nation in a Christmas Day editorial. -

Les Évolutions Politiques Au Kenya À L'approche Des Elections 2007

Les évolutions politiques au Kenya à l’approche des elections 2007 Anne Cussac To cite this version: Anne Cussac. Les évolutions politiques au Kenya à l’approche des elections 2007. 2007. halshs- 01208165 HAL Id: halshs-01208165 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01208165 Submitted on 7 Oct 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MAMBO ! La lettre d'information de l'Institut français de recherche en Afrique Volume VI, n° 1; 2007 Les évolutions politiques au Kenya à l'approche des elections 2007 lors que les rumeurs d’une dissolution imminente du Parlement et d’élections générales avant les vacances de Noël se multiplient, l’activité Apolitique kenyane paraît s’intensifier. En moins d’un mois, les trois principaux candidats à la présidentielle, Mwai Kibaki, Raila Odinga et Kalonzo Musyoka, ont successivement lancé leur campagne électorale, s’appuyant respectivement sur le Party of National Unity (PNU), l’Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) et l’Orange Democratic Movement of Kenya (ODM-K). De plus, et pour attirer les électeurs, les deux favoris, Mwai Kibaki et Raila Odinga semblent mobiliser leurs alliés-clé dans les régions stratégiques du pays1.