Bernard Herrmann's Score for Cape Fear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert De Niro's Raging Bull

003.TAIT_20.1_TAIT 11-05-12 9:17 AM Page 20 R. COLIN TAIT ROBERT DE NIRO’S RAGING BULL: THE HISTORY OF A PERFORMANCE AND A PERFORMANCE OF HISTORY Résumé: Cet article fait une utilisation des archives de Robert De Niro, récemment acquises par le Harry Ransom Center, pour fournir une analyse théorique et histo- rique de la contribution singulière de l’acteur au film Raging Bull (Martin Scorcese, 1980). En utilisant les notes considérables de De Niro, cet article désire montrer que le travail de cheminement du comédien s’est étendu de la pré à la postproduction, ce qui est particulièrement bien démontré par la contribution significative mais non mentionnée au générique, de l’acteur au scénario. La performance de De Niro brouille les frontières des classes de l’auteur, de la « star » et du travail de collabo- ration et permet de faire un portrait plus nuancé du travail de réalisation d’un film. Cet article dresse le catalogue du processus, durant près de six ans, entrepris par le comédien pour jouer le rôle du boxeur Jacke LaMotta : De la phase d’écriture du scénario à sa victoire aux Oscars, en passant par l’entrainement d’un an à la boxe et par la prise de soixante livres. Enfin, en se fondant sur des données concrètes qui sont restées jusqu’à maintenant inaccessibles, en raison de la modestie et du désir du comédien de conserver sa vie privée, cet article apporte une nouvelle perspective pour considérer la contribution importante de De Niro à l’histoire américaine du jeu d’acteur. -

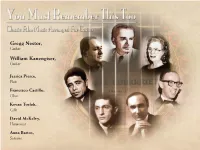

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

The Ethics of Preemptive Action

Danger: The Ethics of Preemptive Action Larry Alexander* & Kimberly Kessler Ferzan"* The law has developed principlesfor dealing with morally and legally responsible actors who act in ways that endanger others, the principles governing crime and punishment. And it has developed principles for dealing with the morally and legally nonresponsible but dangerous actors, the principles governing civil commitments. It has failed, however, to develop a cogent andjustifiable set ofprinciples for dealing with responsible actors who have not yet acted in ways that endanger, others but who are likely to do so in the future, those whom we label "responsible but dangerous" actors (RBDs). Indeed, as we argue, the criminal law has sought to punish RBDs through its expansive use of inchoate criminality; however, current criminalization and punishment practicespunish those who have yet to perform a culpable act. In this article, we attempt to establish defensible grounds for preventive restrictions of liberty (PRLs) of RBDs in lieu of contorting the criminal law. Specifically, we argue that just as a culpable aggressor becomes liable to defensive force, an RBD can become liable to PRLs more generally. Although there are many examples ofPRLs of RBDs currently in operation, the principles, if any, thatjustify and limit such PRLs have yet to be satisfactorilyestablished. In the movie Cape Fear, Sam Bowden, a lawyer in New Essex, North Carolina, is menaced by a recently released convict, Max Cady, whom Bowden had, in Cady's view, inadequately defended against a charge of a violent sexual crime.' In the first movie version, Bowden was played by Gregory Peck and Cady by Robert Mitchum; in the remake, Bowden was played by Nick Nolte and Cady by Robert DeNiro-with Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum now making cameo appearances respectively as a lawyer and police officer. -

An Examination of Jerry Goldsmith's

THE FORBIDDEN ZONE, ESCAPING EARTH AND TONALITY: AN EXAMINATION OF JERRY GOLDSMITH’S TWELVE-TONE SCORE FOR PLANET OF THE APES VINCENT GASSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY 2019 © VINCENT GASSI, 2019 ii ABSTRACT Jerry GoldsMith’s twelve-tone score for Planet of the Apes (1968) stands apart in Hollywood’s long history of tonal scores. His extensive use of tone rows and permutations throughout the entire score helped to create the diegetic world so integral to the success of the filM. GoldsMith’s formative years prior to 1967–his training and day to day experience of writing Music for draMatic situations—were critical factors in preparing hiM to meet this challenge. A review of the research on music and eMotion, together with an analysis of GoldsMith’s methods, shows how, in 1967, he was able to create an expressive twelve-tone score which supported the narrative of the filM. The score for Planet of the Apes Marks a pivotal moment in an industry with a long-standing bias toward modernist music. iii For Mary and Bruno Gassi. The gift of music you passed on was a game-changer. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Heartfelt thanks and much love go to my aMazing wife Alison and our awesome children, Daniela, Vince Jr., and Shira, without whose unending patience and encourageMent I could do nothing. I aM ever grateful to my brother Carmen Gassi, not only for introducing me to the music of Jerry GoldsMith, but also for our ongoing conversations over the years about filM music, composers, and composition in general; I’ve learned so much. -

Your Concert Guide

silver screen sounds your concert guide EDEN COURT caird hall tramway the queen's hall INVERNESS dundee glasgow edinburgh 10 Sep 14 Sep 15 Sep 16 Sep welcome to silver screen sounds Over the course of the concert, you'll hear music chosen to accompany films and extracts from scores written specifically for the screen. There'll be pauses between some, and others will flow into the next. We recommend following along with your listings insert, and using this guide as extra reading. 1 by Bernard Herrmann Prelude from Psycho psycho (1960) Directed by Alfred Hitchcock "When a director finds a composer who understands them, who can get inside their head, who can second-guess them correctly, they're just going to want to stick with that person. And Psycho... it was just one of these absolute instant connections of perfect union of music and image, and Hitchcock at his best, and Bernard Herrmann at his best." Film composer Danny Elfman Herrmann's now-equally-iconic soundtrack to Hitchcock's iconic film showed generations of filmmakers to come the power that music could have. It's a rare example of a film score composed for strings only, a restriction of tonal colour that was, according to an interview with Herrmann, intended as the musical equivalent of Hitchcock's choice of black and white (Hitchcock had originally requested a jazz score, as well as for the shower scene to be silent; Herrmann clearly decided he knew better). Also known as the 'Psycho theme', this prelude is frenetic and fast-paced, suggesting flight and pursuit. -

Adventures in Film Music Redux Composer Profiles

Adventures in Film Music Redux - Composer Profiles ADVENTURES IN FILM MUSIC REDUX COMPOSER PROFILES A. R. RAHMAN Elizabeth: The Golden Age A.R. Rahman, in full Allah Rakha Rahman, original name A.S. Dileep Kumar, (born January 6, 1966, Madras [now Chennai], India), Indian composer whose extensive body of work for film and stage earned him the nickname “the Mozart of Madras.” Rahman continued his work for the screen, scoring films for Bollywood and, increasingly, Hollywood. He contributed a song to the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006) and co- wrote the score for Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007). However, his true breakthrough to Western audiences came with Danny Boyle’s rags-to-riches saga Slumdog Millionaire (2008). Rahman’s score, which captured the frenzied pace of life in Mumbai’s underclass, dominated the awards circuit in 2009. He collected a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for best music as well as a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for best score. He also won the Academy Award for best song for “Jai Ho,” a Latin-infused dance track that accompanied the film’s closing Bollywood-style dance number. Rahman’s streak continued at the Grammy Awards in 2010, where he collected the prize for best soundtrack and “Jai Ho” was again honoured as best song appearing on a soundtrack. Rahman’s later notable scores included those for the films 127 Hours (2010)—for which he received another Academy Award nomination—and the Hindi-language movies Rockstar (2011), Raanjhanaa (2013), Highway (2014), and Beyond the Clouds (2017). -

This Is a Course Designed for Upper-Level Students. It

1 FA 483 Special Topics: Film Scores: Meaning and Music in Cinema Ufuk Çakmak Department of Western Languages an Literatures TTT 678 THIS IS A COURSE DESIGNED FOR UPPER-LEVEL STUDENTS. IT REQUIRES HARD-WORK, A GOOD DEAL OF INTERPRETATIVE CAPACITY, A REAL CURIOSITY TOWARDS THE GREAT MASTERS OF CINEMA AND FILM MUSIC. IF YOU ARE LOOKING FOR A LIGHT COURSE, DON’T TAKE THIS COURSE. NO BOX-OFFICE, COMMERCIAL FILMS. NOT SUITABLE FOR FIRST THREE SEMESTER STUDENTS. Course Description This is a course in film music and cinematic meaning, an attempt to understand creation of meaning through music on the silver screen. Because of its very nature, the course involves two different genres of art: music and cinema. This makes it heavier in course work, as the number of items to be covered multiply by two. You will have screening homeworks on one side where you will screen whole films in their entirety or evaluate excerpts, and you will have pure listening homeworks on the other side, on albums and tracks. You will be requested to write short and/or long response papers on assignments. Although, the course is entitled “Film Scores”, it does not discriminate other meaning formative elements of cinema, and aims at a holistic understanding of the films it tackles. Therefore, you shouldn’t expect a course in pure music. This is a course in both cinema and music. The films I dwell are not commercially oriented, box office films. I’m interested in works of art that search for a profound meaning in an existential journey. -

Music and the Moving Image XVI MAY 28 – MAY 31, 2020 BIOS

Music and the Moving Image XVI MAY 28 – MAY 31, 2020 BIOS Marcos Acevedo-Arús is a music theorist from Puerto Rico. Marcos is currently a graduate student and teaching assistant at Temple University in Philadelphia, PA, studying towards a Master of Music degree in Music Theory. Marcos received his undergraduate degree in Piano Performance from the Puerto Rico Music Conservatory in San Juan, PR in 2015. Marcos’ current interests include video game and pop music analysis, music cognition, musical narrative, and affect theory. Marcos’ previous presentations include “Conflicts and Contrasts in Isaac Albéniz’s ‘Córdoba’” in the 5th Symposium of Musical Research “Puentes Caribeños”. Stephen Amico is Associate Professor of Musicology at the Grieg Academy/University of Bergen, Norway. He has published widely in the areas of popular music studies, Russian and post-Soviet popular culture, and gender and sexuality. His recent work has appeared in the journal Popular Music and Society and The Oxford Handbook of Music and Queerness, with forthcoming work to appear in The Oxford Handbook of Phenomenological Ethnomusicology and the Journal of Musicology. Richard Anatone is a pianist, composer, writer, teacher, and editor. He completed his Doctoral degree in piano performance from Ball State University, and currently serves as Professor of Music at Prince George’s Community College in Maryland. His primary interests are rooted in the music of Nobuo Uematsu, the use of humor and music in games, and early chiptunes, and has presented his research at NACVGM, SCI, and CMS conferences. He is currently editing a collection of chapters on the music Nobuo Uematsu in the soundtracks to the Final Fantasy video game series. -

Bad Lawyers in the Movies

Nova Law Review Volume 24, Issue 2 2000 Article 3 Bad Lawyers in the Movies Michael Asimow∗ ∗ Copyright c 2000 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Asimow: Bad Lawyers in the Movies Bad Lawyers In The Movies Michael Asimow* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 533 I. THE POPULAR PERCEPTION OF LAWYERS ..................................... 536 El. DOES POPULAR LEGAL CULTURE FOLLOW OR LEAD PUBLIC OPINION ABOUT LAWYERS? ......................................................... 549 A. PopularCulture as a Followerof Public Opinion ................ 549 B. PopularCulture as a Leader of Public Opinion-The Relevant Interpretive Community .......................................... 550 C. The CultivationEffect ............................................................ 553 D. Lawyer Portrayalson Television as Compared to Movies ....556 IV. PORTRAYALS OF LAWYERS IN THE MOVIES .................................. 561 A. Methodological Issues ........................................................... 562 B. Movie lawyers: 1929-1969................................................... 569 C. Movie lawyers: the 1970s ..................................................... 576 D. Movie lawyers: 1980s and 1990s.......................................... 576 1. Lawyers as Bad People ..................................................... 578 2. Lawyers as Bad Professionals .......................................... -

A R C R E E L M U S

ARCREELMUSIC The Royal Conservatory of Music 90 Croatia Street Toronto, Ontario, m6h 1k9 Canada Tel 416.408.2824 www.rcmusic.ca TWO PROGRAMS DEVOTED TO THE CHAMBER MUSIC OF FILM COMPOSERS PRESENTED BY ARC IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE ROM BUILDING NATIONAL DREAMS Since 1886, The Royal Conservatory of Music has been a national leader in music and arts education. To provide an even wider reach for its innovative programs, the Conservatory has launched the Building National Dreams Campaign to restore its historic Victorian home and build a state-of-the-art performance and learning centre. Opening in 2007, the TELUS Centre for Performance and Learning will be one of the world’s greatest arts and education venues and a wonderful resource for all Canadians. Designed by Kuwabara Payne McKenna Blumberg Architects (KPMB), this stunning facility will feature new academic and performance space, including an acoustically perfect 1,000-seat concert hall, new studios and classrooms, a new-media centre, library and rehearsal hall. Technologically sophisticated, it will be the heart of creative education in Canada. To get involved in the Building National Dreams Campaign, please call 416.408.2824, ext. 238 or visit www.rcmusic.ca Although the ARC ensemble was founded just three years ago, it has already established itself as a formidable musical presence. The group’s appearances in Toronto, New York, Stockholm and London; several national and NPR broadcasts and the auspicious Music Reborn project, presented in December 2003, have all been greeted with enormous enthusiasm. With Reel Music, ARC explores the chamber works of composers generally associated with film music, and the artistic effects of the two disciplines on each other. -

January 2011 Boulder County Bar Foundation

BOULDER COUNTY BAR NEWSLETTER J A N U A R Y 2 0 1 1 LEGAL AID FOUNDATION OF COLORADO IS AN ORGANIZATION WORKING TO PROVIDE FREE CIVIL LEGAL ASSISTANCE TO LOW-INCOME FAMILIES, SENIOR CITIZENS, DISABLED PERSONS AND VICTIMS OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE. PREMIERE EVENT SPONSOR YOUR FIRM OR COMPANY SPONSORSHIP IS NEEDED FOR THIS EVENT PLEASE CONACT THE BAR OFFICE FOR TAX-DEDUCTIBLE DONATION INFORMATION 303.440.4758 TABLE OF CONTENTS CALENDAR OF EVENTS 2 FOUNDATION FELLOWS 3 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 5 LAWYER ANNOUNCEMENTS 6 & 7 PRO BONO PAGE 9 CLASSIFIED ADS 11 CALENDAR OF EVENTS Pre-registration is required for all BCBA CLE programs. Register by e-mailing [email protected], or pay online with a credit card at www.boulder-bar.org/calendar. You will be charged for your lunch if you make a reservation and do not cancel prior to the CLE meeting. BCBA CLE’s cost for members is $20 per credit hour, $10 for New/Young lawyers practicing three years or less. $25 for non-members. Tuesday, January 11 Tuesday, January 18 Thursday, January 20 Employment Law Paralegals and All Lawyers Bankruptcy Lunch and meeting Tax Issues for Employment Lawyers Casemaker: Making It Work For You Noon at Agave Presenter: Susan Lindley Presenter: Reba Nance Noon at Caplan and Earnest Noon at Caplan and Earnest Wednesday, January 26 1 CLE $20, $10 for new/young lawyers 1 CLE $20, $10 for new/young lawyers Taxation, Estate Planning and Probate Lunch $10 (turkey, veggie, beef or Lunch $10 The CLASS ACT: Community Living salad w/ or w/o meat) Assistance Services and Supports Wednesday,