The Representation of Disability in the Music of Alfred Hitchcock Films John T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bilderna Av Kent 10/13/03 8:13

Bilderna av Kent 10/13/03 8:13 Volume 6 (2003) © Lars Lilliestam, 2003 Bilderna av Kent En fallstudie av musikjournalistik, autenticitet och musikmytologi Lars Lilliestam INLEDNING [1] Musik och berättande Musik är mer än bara musik. Musik är mer än det som klingar. Vi hör alltid musik genom filter av förförståelse, förväntningar, fördomar eller kunskaper. Om man vill försöka förstå vilken verkan musik har och vad den betyder för människor, måste man ta i beaktande vad människor berättar om musiken. Berättandet – vad som skrivs om musik och hur människor talar om musik – laddar musiken med föreställningar, ideologier, värden. Mening uppstår när musiken, människan och berättelserna om musiken möts. Vi tänker, talar eller läser om musik för att bearbeta och jämföra våra egna upplevelser med andras. Genom denna process skapar och utvecklar vi en inre bild av musiken och upplevelsen av den. Berättelser om musiker, musikskapare, musikverk eller låtar, gåtor och oklarheter i verks historia, uttolkningar, tragiska eller på annat sätt fascinerande och gripande levnadsöden och skandaler färgar upplevelsen av musiken. Tänk på historierna om Beethovens dövhet, skandalerna vid premiären av Stravinskijs Våroffer 1913, Bob Dylans framträdande vid Newport Folk Festival 1965, eller mysteriet kring bluessångerskan Bessie Smiths död... Kring artister och genrer spinns en samling berättelser och anekdoter (skrönor, myter, legender) av olika slag – ett narrativ. Dessa berättelser sprids i olika former (intervjuer, reportage, biografier, historiska översikter, recensioner, krönikor) i olika medier (fack- och dagspress, böcker, tv, radio, internet) och muntligen man och man emellan i ett komplicerat och näst intill oöverblickbart spel. Vissa berättelser kan vara skapade av exempelvis ett skivbolag i syfte att understryka en viss image, andra har sitt upphov bland publik, fans eller skribenter. -

Science, Values, and the Novel

Science, Values, & the Novel: an Exercise in Empathy Alan C. Hartford, MD, PhD, FACR Associate Professor of Medicine (Radiation Oncology) Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth 2nd Annual Symposium, Arts & Humanities in Medicine 29 January 2021 The Doctor, 1887 Sir Luke Fildes, Tate Gallery, London • “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.” From: Francis W. Peabody, “The Care of the Patient.” JAMA 1927; 88: 877-882. Francis Weld Peabody, MD 1881-1927 Empathy • Empathy: – “the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.” • Cognitive (from: Oxford Languages) • Affective • Somatic • Theory of mind: – “The capacity to identify and understand others’ subjective states is one of the most stunning products of human evolution.” (from: Kidd and Castano, Science 2013) – Definitions are not full agreed upon, but this distinction is: • “Affective” and “Cognitive” empathy are independent from one another. Can one teach empathy? Reading novels? • Literature as a “way of thinking” – “Literature’s problem is that its irreducibility … makes it look unscientific, and by extension, soft.” – For example: “‘To be or not to be’ cannot be reduced to ‘I’m having thoughts of self-harm.’” – “At one and the same time medicine is caught up with the demand for rigor in its pursuit of and assessment of evidence, and with a recognition that there are other ways of doing things … which are important.” (from: Skelton, Thomas, and Macleod, “Teaching literature -

Why Acting Matters Yale

why acting matters Yale University Press New Haven and London David Thomson Why Acting Matters “Why X Matters” Published with assistance from the foundation and the yX logo are established in memory of Henry Weldon Barnes registered trademarks of the Class of 1882, Yale College. of Yale University. Yale University Press books may be purchased in Copyright © quantity for educational, business, or promotional 2015 by David use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] Thomson. (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). All rights reserved. Set in Times Roman and Adobe Garamond types by This book may not Integrated Publishing Solutions. be reproduced, Printed in the United States of America. in whole or in part, including Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data illustrations, in any Thomson, David, 1941–. Why acting matters / David form (beyond that Thomson. copying permitted by pages cm—(Why X matters) Sections 107 and 108 Includes bibliographical references. of the U.S. Copy- ISBN 978-0-300-19578-1 (cloth : alk. right Law and except paper) 1. Acting. I. Title. by reviewers for the PN2061.T525 2015 public press), without 792.0298—dc23 written permission 2014029867 from the publishers. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Also by David Thomson The New Biographical Dictionary of Film (sixth edition, 2014; first edition, as A Biographical Dictionary of Film, 1975) Moments That Made the Movies (2013) The Big Screen: The Story of the Movies (2012) Try to Tell the Story: A Memoir (2009) The Moment of Psycho: How Alfred Hitchcock Taught America to Love Murder (2009) “Have You Seen . -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

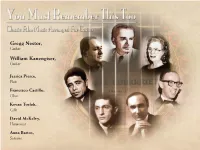

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Understanding Screenwriting'

Course Materials for 'Understanding Screenwriting' FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 Evan Wm. Cameron Professor Emeritus Senior Scholar in Screenwriting Graduate Programmes, Film & Video and Philosophy York University [Overview, Outline, Readings and Guidelines (for students) with the Schedule of Lectures and Screenings (for private use of EWC) for an extraordinary double-weighted full- year course for advanced students of screenwriting, meeting for six hours weekly with each term of work constituting a full six-credit course, that the author was permitted to teach with the Graduate Programme of the Department of Film and Video, York University during the academic years 2001-2002 and 2002-2003 – the most enlightening experience with respect to designing movies that he was ever permitted to share with students.] Overview for Graduate Students [Preliminary Announcement of Course] Understanding Screenwriting FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 FA/FILM 4501 A 6.0 & FA/FILM 4501 B 6.0 Understanding Screenwriting: the Studio and Post-Studio Eras Fall/Winter, 2002-2003 Tuesdays & Thursdays, Room 108 9:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. Evan William Cameron We shall retrace within these courses the historical 'devolution' of screenwriting, as Robert Towne described it, providing advanced students of writing with the uncommon opportunity to deepen their understanding of the prior achievement of other writers, and to ponder without illusion the nature of the extraordinary task that lies before them should they decide to devote a part of their life to pursuing it. During the fall term we shall examine how a dozen or so writers wrote within the studio system before it collapsed in the late 1950s, including a sustained look at the work of Preston Sturges. -

Ticket to the Opera SYLLABUS

Ticket to the Opera Fall, 2018 SYLLABUS All of us, opera connoisseurs, amateurs and newBies alike, are here to savor great music, learn aBout an art form, share perceptions and opinions, and enjoy each other’s company. Participation in class discussion is highly encouraged. Presentations are also encouraged and are meant to Be an interesting learning experience, shared with interested learners. ALL contriButions are welcome and valued. Class #1: Thursday, SeptemBer 13 • Introduction to the class—ice breaker: Penney (20 minutes) • Introduction to the co-coordinators: Penney, Penny, Linda (10 mins) • Preview of the performances: Aida (& Netrebko), Linda Samson & La Fanciulla, Penny Marnie, Penney (20 minutes total) Second hour • A quick history of opera: Penney (30 minutes) • Syllabus: Penney (15 minutes) • Introduce First Listening Challenge (15 minutes) Class #2: Thursday, SeptemBer 20 AIDA • Discuss Listening Challenge (20 minutes) • Verdi biography (15 minutes) • The story/libretto/librettist (15 minutes) Second hour • The Italian legacy in Opera (from the Baroque to the Modern) (30 minutes) • Arias to look forward to, what to listen for: Penny (30 minutes) • Listening Challenge: Which tenor do you prefer? Which soprano? Class #3 Thursday, September 27 AIDA • Discuss Listening (20 minutes) • Cast: Spotlight on the performers: (30 minutes) o Anna Netrebko + Anita Rachvelishvili o Aleksandrs Antonenko + Quinn Kelsey o Dmitry Belosselskiy + Ryan Speedo Green Second hour • Stories from the class: Aida’s you have seen (15 minutes) • Past -

Sur Nos Écrans

Document generated on 09/23/2021 12:16 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Sur nos écrans Number 109, July 1982 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/51015ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review (1982). Review of [Sur nos écrans]. Séquences, (109), 33–48. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 1982 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ • •••a ••**! vISSING (Porté disparu...) • En fication de l'oeuvre. S'il entre dans le débat politi attribuant sa Palme d'or conjointement à que, il court le danger de négliger la portée du film deux films politiques: Missing et Yol, le en soi, au bénéfice des positions idéologiques Festival de Cannes vient de souligner, préétablies. pour la deuxième fois consécutive, le rôle Ayant vécu pendant seize ans en Amérique croissant du cinéma comme témoin de notre temps. latine, j'ai pu me rendre compte des complexités qui L'année dernière, c'était L'Homme de Fer qui exal caractérisent chacun des pays dans cette région. tait la lutte des travailleurs contre un régime se récla C'est pourquoi je me refuse d'accepter les thèses mant du marxisme. -

Hitchcock's Appetites

McKittrick, Casey. "The pleasures and pangs of Hitchcockian consumption." Hitchcock’s Appetites: The corpulent plots of desire and dread. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 65–99. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501311642.0007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 16:41 UTC. Copyright © Casey McKittrick 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 The pleasures and pangs of Hitchcockian consumption People say, “ Why don ’ t you make more costume pictures? ” Nobody in a costume picture ever goes to the toilet. That means, it ’ s not possible to get any detail into it. People say, “ Why don ’ t you make a western? ” My answer is, I don ’ t know how much a loaf of bread costs in a western. I ’ ve never seen anybody buy chaps or being measured or buying a 10 gallon hat. This is sometimes where the drama comes from for me. 1 y 1942, Hitchcock had acquired his legendary moniker the “ Master of BSuspense. ” The nickname proved more accurate and durable than the title David O. Selznick had tried to confer on him— “ the Master of Melodrama ” — a year earlier, after Rebecca ’ s release. In a fi fty-four-feature career, he deviated only occasionally from his tried and true suspense fi lm, with the exceptions of his early British assignments, the horror fi lms Psycho and The Birds , the splendid, darkly comic The Trouble with Harry , and the romantic comedy Mr. -

Innovators: Filmmakers

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: FILMMAKERS David W. Galenson Working Paper 15930 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15930 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2010 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by David W. Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Filmmakers David W. Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15930 April 2010 JEL No. Z11 ABSTRACT John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock were experimental filmmakers: both believed images were more important to movies than words, and considered movies a form of entertainment. Their styles developed gradually over long careers, and both made the films that are generally considered their greatest during their late 50s and 60s. In contrast, Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard were conceptual filmmakers: both believed words were more important to their films than images, and both wanted to use film to educate their audiences. Their greatest innovations came in their first films, as Welles made the revolutionary Citizen Kane when he was 26, and Godard made the equally revolutionary Breathless when he was 30. Film thus provides yet another example of an art in which the most important practitioners have had radically different goals and methods, and have followed sharply contrasting life cycles of creativity. -

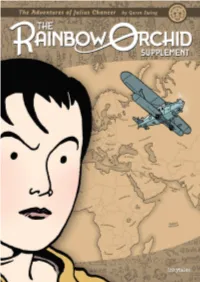

Download the Expanded Digital Edition Here

Spring 1999 December 2002 April 2002 February 2003 May 2003 September 2003 November 2003 October 2004 March 2005 October 2003 November 2007 August 2009 July 2010 April 2012 September 2012 September 2010 April 2011 June 2012 June 2012 November 2012 November 2012 November 2012 January 2013 January 2013 January 2013 I created The Rainbow Orchid because making comics is such hard work that I wanted to write and draw one that I could be absolutely certain at least one person would really like – that person being me. It is steeped in all the things I love. From the adventure stories of H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne and Arthur Conan Doyle I took the long build-up to a fantastic element, made all the more amazing because the characters are immersed in the ‘real world’ for so much of the story. From the comics medium I dipped my pen into the European tradition of Hergé, Edgar P. Jacobs, Yves Chaland and the descendents of their ligne claire legacy, along with the strong sense of environment – a believable world – from Asterix and Tintin. Yet I wanted characters and a setting that were very strongly British, without being patriotic. Mixed into all this is my fondness for an involving and compelling plot, and artistic influences absorbed from a wealth of comic artists and illustrators, from Kay Neilsen to Bryan Talbot, and a simple love of history and adventure. No zombies, no bikini-clad gun-toting nubiles, and no teeth-gritting ... grittiness. Just a huge slice of pure adventure, made to go with a big mug of tea.