The Client Who Did Too Much

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science, Values, and the Novel

Science, Values, & the Novel: an Exercise in Empathy Alan C. Hartford, MD, PhD, FACR Associate Professor of Medicine (Radiation Oncology) Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth 2nd Annual Symposium, Arts & Humanities in Medicine 29 January 2021 The Doctor, 1887 Sir Luke Fildes, Tate Gallery, London • “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.” From: Francis W. Peabody, “The Care of the Patient.” JAMA 1927; 88: 877-882. Francis Weld Peabody, MD 1881-1927 Empathy • Empathy: – “the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.” • Cognitive (from: Oxford Languages) • Affective • Somatic • Theory of mind: – “The capacity to identify and understand others’ subjective states is one of the most stunning products of human evolution.” (from: Kidd and Castano, Science 2013) – Definitions are not full agreed upon, but this distinction is: • “Affective” and “Cognitive” empathy are independent from one another. Can one teach empathy? Reading novels? • Literature as a “way of thinking” – “Literature’s problem is that its irreducibility … makes it look unscientific, and by extension, soft.” – For example: “‘To be or not to be’ cannot be reduced to ‘I’m having thoughts of self-harm.’” – “At one and the same time medicine is caught up with the demand for rigor in its pursuit of and assessment of evidence, and with a recognition that there are other ways of doing things … which are important.” (from: Skelton, Thomas, and Macleod, “Teaching literature -

Silent Films of Alfred Hitchcock

The Hitchcock 9 Silent Films of Alfred Hitchcock Justin Mckinney Presented at the National Gallery of Art The Lodger (British Film Institute) and the American Film Institute Silver Theatre Alfred Hitchcock’s work in the British film industry during the silent film era has generally been overshadowed by his numerous Hollywood triumphs including Psycho (1960), Vertigo (1958), and Rebecca (1940). Part of the reason for the critical and public neglect of Hitchcock’s earliest works has been the generally poor quality of the surviving materials for these early films, ranging from Hitchcock’s directorial debut, The Pleasure Garden (1925), to his final silent film, Blackmail (1929). Due in part to the passage of over eighty years, and to the deterioration and frequent copying and duplication of prints, much of the surviving footage for these films has become damaged and offers only a dismal representation of what 1920s filmgoers would have experienced. In 2010, the British Film Institute (BFI) and the National Film Archive launched a unique restoration campaign called “Rescue the Hitchcock 9” that aimed to preserve and restore Hitchcock’s nine surviving silent films — The Pleasure Garden (1925), The Lodger (1926), Downhill (1927), Easy Virtue (1927), The Ring (1927), Champagne (1928), The Farmer’s Wife (1928), The Manxman (1929), and Blackmail (1929) — to their former glory (sadly The Mountain Eagle of 1926 remains lost). The BFI called on the general public to donate money to fund the restoration project, which, at a projected cost of £2 million, would be the largest restoration project ever conducted by the organization. Thanks to public support and a $275,000 dona- tion from Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation in conjunction with The Hollywood Foreign Press Association, the project was completed in 2012 to coincide with the London Olympics and Cultural Olympiad. -

"Sounds Like a Spy Story": the Espionage Thrillers of Alfred

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions 4-29-2016 "Sounds Like a Spy Story": The Espionage Thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock in Twentieth-Century English and American Society, from The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) to Topaz (1969) Kimberly M. Humphries Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Humphries, Kimberly M., ""Sounds Like a Spy Story": The Espionage Thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock in Twentieth-Century English and American Society, from The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) to Topaz (1969)" (2016). Student Research Submissions. 47. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/47 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "SOUNDS LIKE A SPY STORY": THE ESPIONAGE THRILLERS OF ALFRED HITCHCOCK IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND AMERICAN SOCIETY, FROM THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934) TO TOPAZ (1969) An honors paper submitted to the Department of History and American Studies of the University of Mary Washington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors Kimberly M Humphries April 2016 By signing your name below, you affirm that this work is the complete and final version of your paper submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree from the University of Mary Washington. You affirm the University of Mary Washington honor pledge: "I hereby declare upon my word of honor that I have neither given nor received unauthorized help on this work." Kimberly M. -

Hitchcock's Appetites

McKittrick, Casey. "The pleasures and pangs of Hitchcockian consumption." Hitchcock’s Appetites: The corpulent plots of desire and dread. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 65–99. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501311642.0007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 16:41 UTC. Copyright © Casey McKittrick 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 The pleasures and pangs of Hitchcockian consumption People say, “ Why don ’ t you make more costume pictures? ” Nobody in a costume picture ever goes to the toilet. That means, it ’ s not possible to get any detail into it. People say, “ Why don ’ t you make a western? ” My answer is, I don ’ t know how much a loaf of bread costs in a western. I ’ ve never seen anybody buy chaps or being measured or buying a 10 gallon hat. This is sometimes where the drama comes from for me. 1 y 1942, Hitchcock had acquired his legendary moniker the “ Master of BSuspense. ” The nickname proved more accurate and durable than the title David O. Selznick had tried to confer on him— “ the Master of Melodrama ” — a year earlier, after Rebecca ’ s release. In a fi fty-four-feature career, he deviated only occasionally from his tried and true suspense fi lm, with the exceptions of his early British assignments, the horror fi lms Psycho and The Birds , the splendid, darkly comic The Trouble with Harry , and the romantic comedy Mr. -

Download the Expanded Digital Edition Here

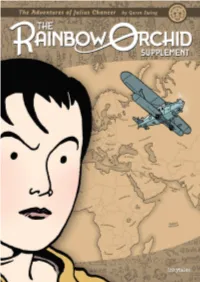

Spring 1999 December 2002 April 2002 February 2003 May 2003 September 2003 November 2003 October 2004 March 2005 October 2003 November 2007 August 2009 July 2010 April 2012 September 2012 September 2010 April 2011 June 2012 June 2012 November 2012 November 2012 November 2012 January 2013 January 2013 January 2013 I created The Rainbow Orchid because making comics is such hard work that I wanted to write and draw one that I could be absolutely certain at least one person would really like – that person being me. It is steeped in all the things I love. From the adventure stories of H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne and Arthur Conan Doyle I took the long build-up to a fantastic element, made all the more amazing because the characters are immersed in the ‘real world’ for so much of the story. From the comics medium I dipped my pen into the European tradition of Hergé, Edgar P. Jacobs, Yves Chaland and the descendents of their ligne claire legacy, along with the strong sense of environment – a believable world – from Asterix and Tintin. Yet I wanted characters and a setting that were very strongly British, without being patriotic. Mixed into all this is my fondness for an involving and compelling plot, and artistic influences absorbed from a wealth of comic artists and illustrators, from Kay Neilsen to Bryan Talbot, and a simple love of history and adventure. No zombies, no bikini-clad gun-toting nubiles, and no teeth-gritting ... grittiness. Just a huge slice of pure adventure, made to go with a big mug of tea. -

Orange County Board of Commissioners Agenda Business

Orange County Board of Commissioners Agenda Business Meeting Note: Background Material December 10, 2019 on all abstracts 7:00 p.m. available in the Southern Human Services Center Clerk’s Office 2501 Homestead Road Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Compliance with the “Americans with Disabilities Act” - Interpreter services and/or special sound equipment are available on request. Call the County Clerk’s Office at (919) 245-2130. If you are disabled and need assistance with reasonable accommodations, contact the ADA Coordinator in the County Manager’s Office at (919) 245-2300 or TDD# 919-644-3045. 1. Additions or Changes to the Agenda PUBLIC CHARGE The Board of Commissioners pledges its respect to all present. The Board asks those attending this meeting to conduct themselves in a respectful, courteous manner toward each other, county staff and the commissioners. At any time should a member of the Board or the public fail to observe this charge, the Chair will take steps to restore order and decorum. Should it become impossible to restore order and continue the meeting, the Chair will recess the meeting until such time that a genuine commitment to this public charge is observed. The BOCC asks that all electronic devices such as cell phones, pagers, and computers should please be turned off or set to silent/vibrate. Please be kind to everyone. Arts Moment – Andrea Selch joined the board of Carolina Wren Press 2001, after the publication of her poetry chapbook, Succory, which was #2 in the Carolina Wren Press poetry chapbook series. She has an MFA from UNC-Greensboro, and a PhD from Duke University, where she taught creative writing from 1999 until 2003. -

Chapter Six—Vertigo (Hitchcock 1958)

Chapter Six—Vertigo (Hitchcock 1958) Cue The Maestro The Vertigo Shot—the stylized moment par excellence Title Sequence The Ever-Widening Circle Libestod Endings The Next Day? Dreaming in Color: A shot-by-shot analysis of the Nightmare sequence Splitting POV The Authorial Camera Cue The Maestro Indeed, Bernard Hermann’s opening musical figure for Vertigo (Hitchcock 1958), heard over the Paramount logo (a circle of stars surround the text “A Paramount Release” superimposed on two snow-capped mountains) immediately announces musically the repetitive and circular nature of Scotty’s repetition compulsion—Freud’s term for the human penchant to repeat traumatic events in order to gain mastery over them—as it reinforces the film’s own circularity. We hear a rising and falling figure of strings and winds punctuated by a brassy blast. This musical motif is repeated later during Scotty’s realization of his fear of heights, produced this time over the “vertigo shot” by a harp glissando which continuously scales up and down the instrument with no discernible root note, and again is disrupted by brass, namely muted trumpets. The rapid succession of notes ascending and descending depicts musically and stylistically the instability of the vertigo experience as does the “vertigo shot” with its simultaneous double movement forward and backward. The blast of brass is a sort of sobering punch in the stomach, a musical sting which emphasizes a particularly terrifying or poignant moment. The Vertigo Shot—the stylized moment par excellence Hitchcock’s famous vertigo shot—a tracking in one direction while simultaneously zooming in the opposite direction—is probably cinema’s stylized moment par excellence in that it is a technical innovation that translates brilliantly into meaning for this film, although admittedly that meaning is so literal that it practically qualifies as a “Mickey Finn” shot like Spade’s pov in Maltese Falcon after being drugged. -

Inside Frame: the Hysteric's Choice

inside frame: the hysteric’s choice By mapping Lacan’s system of four discourses on to the ‘cone of vision’ diagram, it becomes clear that the dis- course of the hysteric depends critically on the function of the ‘inside frame’ — the detail, object, or event that inverts the point of view and the POV’s relation to the vanishing point (VP). The field of production links desire (a) with the Master (master signifier, 1S ). This explains how, as Zizek puts it, cinema is the not simply an illustration of psychic structures but it’s the ‘place we go’ to learn how to respond to the perplexing demands of pleasure. 1. suture: the logic of inside-out Hitchcock’s filmNotorious (1946): the American spy Devlin and his accomplice, Ali- cia, plan to investigate the cellar of her Nazi-spy husband, Sebastian, during a party. To build the tension, a slow boom shot takes the camera’s view from a long high shot above guests arriving in the foyer to a tightly framed shot of the cellar key that Alicia has snitched from her husband’s key-ring. Her clenched fist opens to show the key just as the camera ‘arrives’ at the extreme end of its magnification. This results in a ‘flip’ of space: while we are still able to consciously monitor the progress of the party, we are now aware of the counter-plot to get into the cellar through the ‘inside frame’ that expands outward from the key. Hitchcock sets in motion a ‘ticking clock’ device. As the guests begin to finish off the champaign, Sebastian may need to give the butler the cellar key; if he does, he will notice that it is missing from his key ring and investigate. -

Macguffin Film Working Title: Process Junkies

Don’t Get Sued! Th is script is available through the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 licence. As a way of showing thanks, please be aware of the screenwriter’s neurosis. Screenwriters are very particular about how they receive credit, and this script is no exception. While your fi lm project is essentially yours, please adhere to these guidelines when giving screen writing credit. If you use the screenplay with no modifi cations to it, credit me the following way: Screenplay by M. Robert Turnage, 26screenplays.com If you use the screenplay and modify it less than 50%, credit me the following way: Screenplay by M. Robert Turnage, 26screenplays.com and [Your name] If you use the screenplay and modify it between 51 and 90%, credit me the following way: Screenplay by [Your name] and M. Robert Turnage, 26screenplays.com If you use the screenplay and modify it more than 90%, credit me the following way: Original story by M. Robert Turnage, 26screenplays.com And if you just like the 26 Screenplays project or the idea of Creative Commons screenplays, feel free to show your support by adding the following credit to your fi lm: Special thanks to M. Robert Turnage, 26screenplays.com Of course, another way to show appreciation is to include some reference to the 26screenplays.com web site in your fi lm. Th is can happen by having a character wear a 26 Screenplays T-shirt, having the book displayed in the back- ground someplace, or just mention the web site on a monitor somewhere in your project. -

Factfile: Gce As Level Moving Image Arts the Influence of Alfred Hitchcock’S Cinematic Style

FACTFILE: GCE AS LEVEL MOVING IMAGE ARTS THE INFLUENCE OF ALFRED HITCHCOCK’S CINEMATIC STYLE The influence of Alfred Hitchcock’s Cinematic Style Learning outcomes Students should be able to: • explain the influence of Hitchcock’s cinematic style on the work of contemporary filmmakers; and • analyse the cinematic style of filmmakers who have been influenced by Hitchcock. Course Content Alfred Hitchcock’s innovative approach to visual In the 1970’s, as his career was coming to an storytelling and the central themes of his work have end, Hitchcock was a seminal influence on the had a profound influence on world cinema, shaping young directors of the New Hollywood, including film genres such as crime and horror and inspiring Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin generations of young directors to experiment with Scorsese and Brian De Palma. Over the past four film language. decades, this influence has expanded greatly with Hitchcock’s body of work functioning as a virtual In Paris in the 1960’s, French New Wave directors, film school for learning the rules of the Classical Francois Truffaut and Claude Chabrol embraced Hollywood Style, as well as how to break them. The Hitchcock’s dark vision of criminality, while in director’s influence is so far-reaching, that the term London, young Polish director Roman Polanski ‘Hitchcockian’ is now universally applied in the created a terrifying Hitchcockian nightmare in his analysis of contemporary cinema. The directors of debut film, Repulsion (1965). the New Hollywood drew inspiration from a wide range of Hitchcock’s techniques. 1 FACTFILE: GCE AS LEVEL MOVING IMAGE ARTS / THE INFLUENCE OF ALFRED HITCHCOCK’S CINEMATIC STYLE Martin Scorsese through an automated car factory in which the film’s hero is encased in a newly-built vehicle. -

Hitchcock's Screenwriting and Identification

Remaking The 39 Steps Hitchcock’s Screenwriting and Identification Will Bligh May 2018 Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Certificate of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: Date: 18th May 2018 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my principal supervisor, Dr Alex Munt, for his on-going support and commitment to the completion of my research. His passion for film was a constant presence throughout an extended process of developing my academic and creative work. Thanks also to my associate supervisor, Margot Nash, with whom I began this journey when she supervised the first six months of my candidature and helped provide a clear direction for the project. This research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Thanks to Dr Inez Templeton, who edited the dissertation with attention to detail. Lastly, but certainly not least, my wife Esther was a shining light during a process with many ups and downs and provided a turning point in my journey when she helped me find the structure for this thesis. -

BFI | Sight & Sound | Film of the Month: Double Take (0) 21/05/10 12:26

BFI | Sight & Sound | Film of the month: Double Take (0) 21/05/10 12:26 Home > Sight & Sound > April 2010 Film of the month: Double Take More than just a homage, Johan Grimonprez’s extraordinary montage uses Hitch’s mischievous TV appearances as the launch pad for a brilliant riff on Cold War politics and the idea of the double. By Jonathan Romney As all Hitchcockians know, a macguffin is the object of desire in a narrative – the thing that everyone is chasing, but that really has no function except to make the story happen. Hitchcock defined the macguffin in a famous anecdote. A man in a train is asked by another passenger about the mysterious object in the luggage rack; he explains that it is a macguffin, used to hunt lions in the Adirondack Mountains. But there are no lions in the Adirondacks, the other man objects. To which the first imperturbably replies, “Then that’s no macguffin.” In Double Take, Alfred Hitchcock himself is the macguffin – the protean, elusive mystery around which Johan Grimonprez’s extraordinary montage revolves. Hitchcock’s narrative strategies, thematic obsessions and persona have long fascinated artists: Pierre Huyghe and Douglas Gordon are among those who have recently attempted entire or partial remakes – ‘doubles’ – of Hitchcock films. Now the Hitchcockian theme of doubling is the basis of this hybrid film by Belgian film-maker, artist and academic Grimonprez, who previously explored the topic in his 2004 short Looking for Alfred, about his search for Hitchcock lookalikes. In Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y (1997), Grimonprez used archive footage to contemplate our era through a chronicle of airline hijacks.