Review of Charade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule of Exhibitions and Events

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Ro, 102 11 WEST 33 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. FOR RELEASE: TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 September 1, 1962 HOURS: ADMISSION: Weekdays: 11 a.m. - 6 p.m., Thursdays until 9 p.m. Adults: $1.00 Sundays: 1 p.m. T P.m. (Thursday, Sept. 6, until 10 p.m.) Children: 25 2 Members free The final Jazz in the Garden concert will be held Thursday, September 6 at 8:30 p.m. Museum galleries will be open until 10 p.m.; daily film showing repeated at 8 p.m. in the auditorium. Beginning September 13, galleries will be open until 9 p.m. on Thursdays. Special events, including concerts, lectures, symposia and films, will be presented beginning at 8:30 p.m. in tue auditorium. Supper and light refreshments available, SCHEDULE OF EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS Note: Full releases on each exhibition are available five days before the opening. Photographs are available on request from Elizabeth Shaw, Publicity Director. SEPTEMBER OPENING September 12 - MARK TOBEY. A one-man show of about I30 prime paintings, mostly November k from the past two decades. Tobey (b.1890) first won general recognition after World War II, and was the first American painter since Whistler to be awarded an International Grand Prize at the Venice Biennale (1958) ana* the first living American to be given an exhibition at the Louvre in Paris (I96I). The exhibition will be accompanied by an extensive monograph on the artist's work by William Seitz, Associate Curator, Painting and Sculpture Exhibitions who is also directing the show. -

Science, Values, and the Novel

Science, Values, & the Novel: an Exercise in Empathy Alan C. Hartford, MD, PhD, FACR Associate Professor of Medicine (Radiation Oncology) Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth 2nd Annual Symposium, Arts & Humanities in Medicine 29 January 2021 The Doctor, 1887 Sir Luke Fildes, Tate Gallery, London • “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.” From: Francis W. Peabody, “The Care of the Patient.” JAMA 1927; 88: 877-882. Francis Weld Peabody, MD 1881-1927 Empathy • Empathy: – “the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.” • Cognitive (from: Oxford Languages) • Affective • Somatic • Theory of mind: – “The capacity to identify and understand others’ subjective states is one of the most stunning products of human evolution.” (from: Kidd and Castano, Science 2013) – Definitions are not full agreed upon, but this distinction is: • “Affective” and “Cognitive” empathy are independent from one another. Can one teach empathy? Reading novels? • Literature as a “way of thinking” – “Literature’s problem is that its irreducibility … makes it look unscientific, and by extension, soft.” – For example: “‘To be or not to be’ cannot be reduced to ‘I’m having thoughts of self-harm.’” – “At one and the same time medicine is caught up with the demand for rigor in its pursuit of and assessment of evidence, and with a recognition that there are other ways of doing things … which are important.” (from: Skelton, Thomas, and Macleod, “Teaching literature -

Citizen Kane

A N I L L U M I N E D I L L U S I O N S E S S A Y B Y I A N C . B L O O M CC II TT II ZZ EE NN KK AA NN EE Directed by Orson Welles Produced by Orson Welles Distributed by RKO Radio Pictures Released in 1941 n any year, the film that wins the Academy Award for Best Picture reflects the Academy ' s I preferences for that year. Even if its members look back and suffer anxious regret at their choice of How Green Was My Valley , that doesn ' t mean they were wrong. They can ' t be wrong . It ' s not everyone else ' s opinion that matters, but the Academy ' s. Mulling over the movies of 1941, the Acade my rejected Citizen Kane . Perhaps they resented Orson Welles ' s arrogant ways and unprecedented creative power. Maybe they thought the film too experimental. Maybe the vote was split between Citizen Kane and The Maltese Falcon , both pioneering in their F ilm Noir flavor. Or they may not have seen the film at all since it was granted such limited release as a result of newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst ' s threats to RKO. Nobody knows, and it doesn ' t matter. Academy members can ' t be forced to vote for the film they like best. Their biases and political calculations can ' t be dissected. To subject the Academy to such scrutiny would be impossible and unfair. It ' s the Academy ' s awards, not ours. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Teaching Social Issues with Film

Teaching Social Issues with Film Teaching Social Issues with Film William Benedict Russell III University of Central Florida INFORMATION AGE PUBLISHING, INC. Charlotte, NC • www.infoagepub.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russell, William B. Teaching social issues with film / William Benedict Russell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60752-116-7 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-60752-117-4 (hardcover) 1. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Audio-visual aids. 2. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Research. 3. Motion pictures in education. I. Title. H62.2.R86 2009 361.0071’2--dc22 2009024393 Copyright © 2009 Information Age Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface and Overview .......................................................................xiii Acknowledgments ............................................................................. xvii 1 Teaching with Film ................................................................................ 1 The Russell Model for Using Film ..................................................... 2 2 Legal Issues ............................................................................................ 7 3 Teaching Social Issues with Film -

SALLI NEWMAN (818) 618‐1551 (C) * (818) 955‐5711 (O) PRODUCER [email protected] ______

SALLI NEWMAN (818) 618‐1551 (C) * (818) 955‐5711 (O) PRODUCER [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FEATURE FILMS “THE MAGIC OF BELLE ISLE” — Producer (Summer 2012 release) Firebrand Productions/Summer Magic Productions/Castle Rock Entertainment/Magnolia Pictures/Revelations Entertainment Director: Rob Reiner * Cast: Morgan Freeman and Virginia Madsen * Location: Upstate New York “ANOTHER HAPPY DAY” — Producer Mandalay Vision Director: Sam Levinson * Cast: Ellen Barkin, Demi Moore, Kate Bosworth, Thomas Haden Church, Ellen Burstyn, George Kennedy, Jeffrey DeMunn, Ezra Miller * Location: Michigan * Sundance Winner of the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award – Sam Levinson “DAVID & GOLIATH” (Short) — Production Consultant Zaver Productions/Filmmakers Alliance Director: George Zaver * Cast: Billy Burke * Location: Los Angeles * Winner of Various Film Festival Awards including Best Short Film and Best First Time Director “MY ONE AND ONLY” — Consulting Producer Herrick Entertainment Director: Richard Loncraine * Cast: Renee Zellweger, Kevin Bacon, Chris Noth, Logan Lerman * Locations: Baltimore; New Mexico “D2: THE MIGHTY DUCKS” — Co‐Producer Avnet‐Kerner Company/Walt Disney Pictures Director: Sam Weisman * Cast: Emilio Estevez, Joshua Jackson * Locations: Los Angeles; Minneapolis “WHEN A MAN LOVES A WOMAN” — Associate Producer Avnet‐Kerner Company/Touchstone Pictures Director: Luis Mandoki * Cast: Meg Ryan, Andy Garcia * Locations: -

Printable Schedule

Schedule for 9/29/21 to 10/6/21 (Central Time) WEDNESDAY 9/29/21 TIME TITLE GENRE 4:30am Fractured Flickers (1963) Comedy Featuring: Hans Conried, Gypsy Rose Lee THURSDAY 9/30/21 TIME TITLE GENRE 5:00am Backlash (1947) Film-Noir Featuring: Jean Rogers, Richard Travis, Larry J. Blake, John Eldredge, Leonard Strong, Douglas Fowley 6:25am House of Strangers (1949) Film-Noir Featuring: Edward G. Robinson, Susan Hayward, Richard Conte, Luther Adler, Paul Valentine, Efrem Zimbalist Jr. 8:35am Born to Kill (1947) Film-Noir Featuring: Claire Trevor, Lawrence Tierney 10:35am The Power of the Whistler (1945) Film-Noir Featuring: Richard Dix, Janis Carter 12:00pm The Burglar (1957) Film-Noir Featuring: Dan Duryea, Jayne Mansfield, Martha Vickers 2:05pm The Lady from Shanghai (1947) Film-Noir Featuring: Orson Welles, Rita Hayworth, Everett Sloane, Carl Frank, Ted de Corsia 4:00pm Bodyguard (1948) Film-Noir Featuring: Lawrence Tierney, Priscilla Lane 5:20pm Walk the Dark Street (1956) Film-Noir Featuring: Chuck Connors, Don Ross 7:00pm Gun Crazy (1950) Film-Noir Featuring: John Dall, Peggy Cummins 8:55pm The Clay Pigeon (1949) Film-Noir Featuring: Barbara Hale 10:15pm Daisy Kenyon (1947) Romance Featuring: Joan Crawford, Henry Fonda, Dana Andrews, Ruth Warrick, Martha Stewart 12:25am This Woman Is Dangerous (1952) Film-Noir Featuring: Joan Crawford, Dennis Morgan 2:30am Impact (1949) Film-Noir Featuring: Brian Donlevy, Raines Ella FRIDAY 10/1/21 TIME TITLE GENRE 5:00am Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) Thriller Featuring: Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins -

Download the Expanded Digital Edition Here

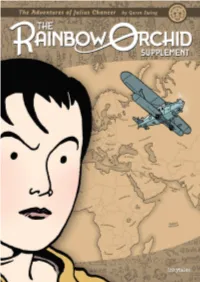

Spring 1999 December 2002 April 2002 February 2003 May 2003 September 2003 November 2003 October 2004 March 2005 October 2003 November 2007 August 2009 July 2010 April 2012 September 2012 September 2010 April 2011 June 2012 June 2012 November 2012 November 2012 November 2012 January 2013 January 2013 January 2013 I created The Rainbow Orchid because making comics is such hard work that I wanted to write and draw one that I could be absolutely certain at least one person would really like – that person being me. It is steeped in all the things I love. From the adventure stories of H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne and Arthur Conan Doyle I took the long build-up to a fantastic element, made all the more amazing because the characters are immersed in the ‘real world’ for so much of the story. From the comics medium I dipped my pen into the European tradition of Hergé, Edgar P. Jacobs, Yves Chaland and the descendents of their ligne claire legacy, along with the strong sense of environment – a believable world – from Asterix and Tintin. Yet I wanted characters and a setting that were very strongly British, without being patriotic. Mixed into all this is my fondness for an involving and compelling plot, and artistic influences absorbed from a wealth of comic artists and illustrators, from Kay Neilsen to Bryan Talbot, and a simple love of history and adventure. No zombies, no bikini-clad gun-toting nubiles, and no teeth-gritting ... grittiness. Just a huge slice of pure adventure, made to go with a big mug of tea. -

Story/Clip English: Writing English: Reading Maths the Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson Pppc8w

Story/Clip English: Writing English: Reading Maths The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson Using descriptions from mouse to describe The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson Cooking: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s8sU the Gruffalo such as ‘He has terrible tusks, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s8sUPpPc8 Make some Purple Prickly pancakes. PpPc8Ws&t=222s (youtube) and terrible claws’ Can they label a picture Ws&t=222s Ingredients: of the Gruffalo? 200g self-raising flour Bear is not tired by Ciara Gavin 1 tbsp golden caster sugar Can you record yourself retelling the story https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HXfzj24mr 3 eggs of the Gruffalo? Maybe you could slither like H8 25g melted butter a snake or fly around like an owl? I would like 200ml milk to hear some animal noises, maybe small Hibernation station by Michelle Meadows Blueberries pitter patter for the mouse’s footsteps and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdbfXs1JbI https://www.bbcgoodfood.com/recipes/ame big heavy ones for the Gruffalo? Q rican-pancakes It is the Gruffalo’s birthday soon and he Snow rabbit, spring rabbit by Sung Na would like to invite his friends to his party. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tnr3eFdVC Can you write one invitation to one of his Z8 friends inviting them to his tea party in the woods? Phonic Bug: https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b The Hunt 00pk64x/the-gruffalo (BBC Short Choose a page from the book. Can you write Following the clues Movie) some speech bubbles for the characters? Rabbits What might they be saying to each other? https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/52153 Problem solving: 696 (Story about social distancing using If the Gruffalo saw 4 owls Monday and 2 on the Gruffalo characters) Tuesday. -

MENANDS ACTIVITIES Published by the Village of Menands

The News of MENANDS ACTIVITIES Published by the Village of Menands 250 Broadway, Menands, NY 12204 Village Office Tel. 518-434-2922 Sheila M. Hyatt, Editor Web Address: www.villageofmenands.com October 16, 2015 Email address: [email protected] VILLAGE BOARD MEETING MAYOR’S MESSAGE (continued) The next Village Board Meeting will be held on turnout of families, and is always fun and educational. Monday, October 19, 2015 at 6:00 p.m. All meetings Another reminder is to change the batteries in your are open to the public and are handicap accessible. smoke and carbon monoxide detectors on Sunday, November 1st, along with turning the clocks back an HEALTH INSURANCE WORKSHOP hour for daylight savings time. A Health Insurance Workshop for Board Members will be held by the Board of Trustees of the Village of Throughout the year, in one way or another, someone in Menands in the Municipal Building of such Village on our Village is consistently helping others. Whether it be Tuesday, October 27, 2015 at 6:00 P.M. Such through volunteer work, organizing functions, fund Workshops are open to the public and are handicap raising efforts or a multitude of other activities, Menands accessible. has always been a giving and caring community. Congratulations to the organizers and volunteers for YOUTH HALLOWEEN FALL PARTY another successful Fall Festival in support of Derek Come join us to celebrate our Halloween-Fall Party on Murphy. It was well attended, had great music, vendors, Sunday, October 25th from 1-3 p.m. at Ganser Smith raffles, cow plop bingo and was a lot of fun. -

Classic Film Festival October 23-26

University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well Campus News Archive Campus News, Newsletters, and Events 8-19-2003 Classic Film Festival October 23-26 University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/urel_news Recommended Citation University Relations, "Classic Film Festival October 23-26" (2003). Campus News Archive. 1873. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/urel_news/1873 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Campus News, Newsletters, and Events at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campus News Archive by an authorized administrator of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contact Melissa Weber, Director of Communications Phone: 320-589-6414, [email protected] Jenna Ray, Editor/Writer Phone: 320-589-6068, [email protected] Classic Film Festival October 23-26 Summary: (August 19, 2003)-Discover a “classic” movie-viewing experience during the Morris Classic Film Festival to be held at the Morris Theatre October 23-26. The fifth annual Festival, sponsored by the Campus Activities Council Films Committee at the University of Minnesota, Morris, will again offer movies “as they were meant to be seen – on the big screen, in all their glory.” This year's lineup is another eclectic mix of classic films, from the raucous wit of Billy Wilder to the psychological complexity of Alfred Hitchcock. Here are the offerings: Thursday October 23 7pm - Funny Face (C,1957) Audrey Hepburn and Fred Astaire. A young woman agrees to model a line of ultra-chic fashions for a photographer so she can get to Paris to meet the beatnik founder of "empathicalism" (a rejection of all material things). -

Bamcinématek Presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 Days of 40 Genre-Busting Films, Aug 5—24

BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 days of 40 genre-busting films, Aug 5—24 “One of the undisputed masters of modern genre cinema.” —Tom Huddleston, Time Out London Dante to appear in person at select screenings Aug 5—Aug 7 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Jul 18, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, August 5, through Wednesday, August 24, BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, a sprawling collection of Dante’s essential film and television work along with offbeat favorites hand-picked by the director. Additionally, Dante will appear in person at the August 5 screening of Gremlins (1984), August 6 screening of Matinee (1990), and the August 7 free screening of rarely seen The Movie Orgy (1968). Original and unapologetically entertaining, the films of Joe Dante both celebrate and skewer American culture. Dante got his start working for Roger Corman, and an appreciation for unpretentious, low-budget ingenuity runs throughout his films. The series kicks off with the essential box-office sensation Gremlins (1984—Aug 5, 8 & 20), with Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates. Billy (Galligan) finds out the hard way what happens when you feed a Mogwai after midnight and mini terrors take over his all-American town. Continuing the necessary viewing is the “uninhibited and uproarious monster bash,” (Michael Sragow, New Yorker) Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990—Aug 6 & 20). Dante’s sequel to his commercial hit plays like a spoof of the original, with occasional bursts of horror and celebrity cameos. In The Howling (1981), a news anchor finds herself the target of a shape-shifting serial killer in Dante’s take on the werewolf genre.