Cinematic Fashionability and Images Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie Actresses 10 Mar 2017

Movie Actresses 10 Mar 2017 251-2017-07 This article is about my favorite movie actresses of all time. Movie critics and most people will not agree with my picks. However, my criteria is quite simple - the actress must have made at least three movies I have seen and liked and would watch again if they happened to come on the TV movie channel when I’m in the mood to see a good show. I’m going to pick my Top 20 Actresses. I could not decide on a header so you can pick the one you like best. Faye Dunaway Sharon Stone Liz Taylor #1 Faye Dunaway Born: Dorothy Faye Dunaway on January 14, 1941 (age 76) in Bascom, Florida Alma mater: Boston University Years active: 1962–present (Appeared in 81 movies) Spouse(s): Peter Wolf (m. 1974–79) Terry O'Neill (m. 1983–87) Children: Liam O'Neill (b. 1980) Facts: The daughter of Grace April, and John MacDowell Dunaway, a career officer in the United States Army. She is of Scots-Irish, English, and German descent. She spent her childhood traveling throughout the United States and Europe. Bonnie and Clyde (1967) with Warren Beatty. In the middle of the Great Depression, Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty) and Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway) meet when Clyde tries to steal Bonnie's mother's car. Bonnie, who is bored by her job as a waitress, is intrigued by Clyde, and decides to take up with him and become his partner in crime. Three Days of the Condor (1975) with Robert Redford. -

Chic Street Oscar De La Renta Addressed Potential Future-Heads-Of-States, Estate Ladies and Grand Ole Party Gals with His Collection of Posh Powerwear

JANET BROWN STORE MAY CLOSE/15 ANITA RODDICK DIES/18 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’TUESDAY Daily Newspaper • September 11, 2007 • $2.00 Ready-to-Wear/Textiles Chic Street Oscar de la Renta addressed potential future-heads-of-states, estate ladies and grand ole party gals with his collection of posh powerwear. Here, he showed polish with an edge in a zip-up leather top and silk satin skirt, topped with a feather bonnet. For more on the shows, see pages 6 to 13. To Hype or Not to Hype: Designer Divide Grows Over Role of N.Y. Shows By Rosemary Feitelberg and Marc Karimzadeh NEW YORK — Circus or salon — which does the fashion industry want? The growing divide between designers who choose to show in the commercially driven atmosphere of the Bryant Park tents of Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week and those who go off-site to edgier, loftier or far-flung venues is defining this New York season, and designers on both sides of the fence argue theirs is the best way. As reported, IMG Fashion, which owns Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week, has signed a deal to keep those shows See The Show, Page14 PHOTO BY GIOVANNI GIANNONI GIOVANNI PHOTO BY 2 WWD, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2007 WWD.COM Iconix, Burberry Resolve Dispute urberry Group plc and Iconix Brand Group said Monday that they amicably resolved pending WWDTUESDAY Blitigation. No details of the settlement were disclosed. Ready-to-Wear/Textiles Burberry fi led a lawsuit in Manhattan federal court on Aug. 24 against Iconix alleging that the redesigned London Fog brand infringed on its Burberry check design. -

The Fashion Runway Through a Critical Race Theory Lens

THE FASHION RUNWAY THROUGH A CRITICAL RACE THEORY LENS A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Sophia Adodo March, 2016 Thesis written by Sophia Adodo B.A., Texas Woman’s University, 2011 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Tameka Ellington, Thesis Supervisor ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Kim Hahn, Thesis Supervisor ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Amoaba Gooden, Committee Member ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Catherine Amoroso Leslie, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The Fashion School ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Linda Hoeptner Poling, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The School of Art ___________________________________________________________ Mr. J.R. Campbell, Director, The Fashion School ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Christine Havice, Director, The School of Art ___________________________________________________________ Dr. John Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. -

Fact Or Fiction: Hollywood Looks at the News

FACT OR FICTION: HOLLYWOOD LOOKS AT THE NEWS Loren Ghiglione Dean, Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University Joe Saltzman Director of the IJPC, associate dean, and professor of journalism USC Annenberg School for Communication Curators “Hollywood Looks at the News: the Image of the Journalist in Film and Television” exhibit Newseum, Washington D.C. 2005 “Listen to me. Print that story, you’re a dead man.” “It’s not just me anymore. You’d have to stop every newspaper in the country now and you’re not big enough for that job. People like you have tried it before with bullets, prison, censorship. As long as even one newspaper will print the truth, you’re finished.” “Hey, Hutcheson, that noise, what’s that racket?” “That’s the press, baby. The press. And there’s nothing you can do about it. Nothing.” Mobster threatening Hutcheson, managing editor of the Day and the editor’s response in Deadline U.S.A. (1952) “You left the camera and you went to help him…why didn’t you take the camera if you were going to be so humane?” “…because I can’t hold a camera and help somebody at the same time. “Yes, and by not having your camera, you lost footage that nobody else would have had. You see, you have to make a decision whether you are going to be part of the story or whether you’re going to be there to record the story.” Max Brackett, veteran television reporter, to neophyte producer-technician Laurie in Mad City (1997) An editor risks his life to expose crime and print the truth. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Puvunestekn 2

1/23/19 Costume designers and Illustrations 1920-1940 Howard Greer (16 April 1896 –April 1974, Los Angeles w as a H ollywood fashion designer and a costume designer in the Golden Age of Amer ic an cinema. Costume design drawing for Marcella Daly by Howard Greer Mitc hell Leis en (October 6, 1898 – October 28, 1972) was an American director, art director, and costume designer. Travis Banton (August 18, 1894 – February 2, 1958) was the chief designer at Paramount Pictures. He is considered one of the most important Hollywood costume designers of the 1930s. Travis Banton may be best r emembered for He held a crucial role in the evolution of the Marlene Dietrich image, designing her costumes in a true for ging the s tyle of s uc h H ollyw ood icons creative collaboration with the actress. as Carole Lombard, Marlene Dietrich, and Mae Wes t. Costume design drawing for The Thief of Bagdad by Mitchell Leisen 1 1/23/19 Travis Banton, Travis Banton, Claudette Colbert, Cleopatra, 1934. Walter Plunkett (June 5, 1902 in Oakland, California – March 8, 1982) was a prolific costume designer who worked on more than 150 projects throughout his career in the Hollywood film industry. Plunk ett's bes t-known work is featured in two films, Gone with the Wind and Singin' in the R ain, in which he lampooned his initial style of the Roaring Twenties. In 1951, Plunk ett s hared an Osc ar with Orr y-Kelly and Ir ene for An Amer ic an in Paris . Adr ian Adolph Greenberg ( 1903 —19 59 ), w i de l y known Edith H ead ( October 28, 1897 – October 24, as Adrian, was an American costume designer whose 1981) was an American costume designer mos t famous costumes were for The Wiz ard of Oz and who won eight Academy Awards, starting with other Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films of the 1930s and The Heiress (1949) and ending with The Sting 1940s. -

THTR 433A/ '16 CD II/ Syllabus-9.Pages

USCSchool of Costume Design II: THTR 433A Thurs. 2:00-4:50 Dramatic Arts Fall 2016 Location: Light Lab/PDE Instructor: Terry Ann Gordon Office: [email protected]/ floating office Office Hours: Thurs. 1:00-2:00: by appt/24 hr notice Contact Info: [email protected], 818-636-2729 Course Description and Overview This course is designed to acquaint students with the requirements, process and expectations for Film/TV Costume Designers, supervisors and crew. Emphasis will be placed on all aspects of the Costume process; Design, Prep: script analysis,“scene breakdown”, continuity, research, and budgeting; Shooting schedules, and wrap. The supporting/ancillary Costume Arts and Crafts will also be discussed. Students will gain an historical overview, researching a variety of designers processes, aesthetics and philosophies. Viewing films and film clips will support critique and class discussion. Projects focused on specific design styles and varied media will further support an overview of techniques and concepts. Current production procedures, vocabulary and technology will be covered. We will highlight those Production departments interacting closely with the Costume Department. Time permitting, extra-curricular programs will include rendering/drawing instruction, select field trips, and visiting TV/Film professionals. Students will be required to design a variety of projects structured to enhance their understanding of Film/TV production, concept, style and technique . Learning Objectives The course goal is for students to become familiar with the fundamentals of costume design for TV/Film. They will gain insight into the protocol and expectations required to succeed in this fast paced industry. We will touch on the multiple variations of production formats: Music Video, Tv: 4 camera vs episodic, Film, Commercials, Styling vs Costume Design. -

GIORGIO MORODER Album Announcement Press Release April

GIORGIO MORODER TO RELEASE BRAND NEW STUDIO ALBUM DÉJÀ VU JUNE 16TH ON RCA RECORDS ! TITLE TRACK “DÉJÀ VU FEAT. SIA” AVAILABLE TODAY, APRIL 17 CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO “DÉJÀ VU FEATURING SIA” DÉJÀ VU ALBUM PRE-ORDER NOW LIVE (New York- April 17, 2015) Giorgio Moroder, the founder of disco and electronic music trailblazer, will be releasing his first solo album in over 30 years entitled DÉJÀ VU on June 16th on RCA Records. The title track “Déjà vu featuring Sia” is available everywhere today. Click here to listen now! Fans who pre-order the album will receive “Déjà vu feat. Sia” instantly, as well as previously released singles “74 is the New 24” and “Right Here, Right Now featuring Kylie Minogue” instantly. (Click hyperlinks to listen/ watch videos). Album preorder available now at iTunes and Amazon. Giorgio’s long-awaited album DÉJÀ VU features a superstar line up of collaborators including Britney Spears, Sia, Charli XCX, Kylie Minogue, Mikky Ekko, Foxes, Kelis, Marlene, and Matthew Koma. Find below a complete album track listing. Comments Giorgio Moroder: "So excited to release my first album in 30 years; it took quite some time. Who would have known adding the ‘click’ to the 24 track would spawn a musical revolution and inspire generations. As I sit back readily approaching my 75th birthday, I wouldn’t change it for the world. I'm incredibly happy that I got to work with so many great and talented artists on this new record. This is dance music, it’s disco, it’s electronic, it’s here for you. -

(QTR) Apparel Program Supercharges Licensing in Complementary Categories Across Isaac Mizrahi, H Halston, and Judith Ripka Brands

November 9, 2016 Xcel Brands, Inc. Quick Time Response (QTR) Apparel Program Supercharges Licensing in Complementary Categories Across Isaac Mizrahi, H Halston, and Judith Ripka Brands NEW YORK, Nov. 09, 2016 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Xcel Brands, Inc. (NASDAQ:XELB) is pleased to announce multiple new licenses across its owned brands as licensees look to pursue growth in categories complementary to Xcel's successful quick time response (QTR) apparel programs at Lord & Taylor and Hudson's Bay stores. CEO and Chairman of Xcel Brands, Inc. Robert W. D'Loren remarked, "With the rise of a ‘see-now-buy-now' consumer shopping mentality and the need to respond to trends as they happen, Xcel created an innovative solution to bring exclusive brands to our department store partners in a quick time response format. The rapid growth of these apparel programs has generated excitement within the licensing community across numerous complementary categories. With these new partnerships we will continue to build meaningful lifestyle brands under the IMNYC Isaac Mizrahi and H Halston labels." New licensees under the Isaac Mizrahi brand include tech accessories and luggage, with product set to retail in Spring 2017. Xcel Brands, Inc. entered into a licensing agreement with Bytech NY Inc. for tech accessories for smartphones, PCs, tablets, and personal audio across the Isaac Mizrahi New York, IMNYC Isaac Mizrahi, and Isaac Mizrahi Live! labels. Xcel also entered into a licensing agreement with Longlat Inc. for a collection of hard and soft luggage under the Isaac Mizrahi New York and Isaac Mizrahi Live! labels. New licensees under the H Halston brand include sleepwear and intimates, legwear and slippers, and non-optical sunglasses and readers. -

Final J.Min |O.Phi |T.Cun |Editor |Copy

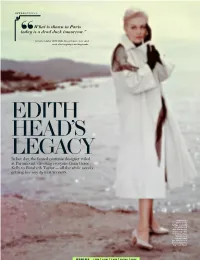

Style SPeCIAl What is shown in Paris today is a dead duck tomorrow.” — Costume designer EDITH HEAD, whose 57-year career owed “ much of its longevity to avoiding trends. C Edith Head’s LEgacy In her day, the famed costume designer ruled at Paramount, dressing everyone from Grace Kelly to Elizabeth Taylor — all the while savvily getting her way By Sam Wasson Kim Novak’s wardrobe for Vertigo, including this white coat with black scarf, was designed to look mysterious. “This girl must look as if she’s just drifted out of the San Francisco fog,” said Head. FINAL J.MIN |O.PHI |T.CUN |EDITOR |COPY Costume designer edith head — whose most unforgettable designs included Grace Kelly’s airy chiffon skirt in Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief, Gloria Swanson’s darkly elegant dresses in Sunset Boulevard, Dorothy Lamour’s sarongs, and Elizabeth Taylor’s white satin gown in A Place in the Sun — sur- vived 40 years of changing Hollywood styles by skillfully eschewing fads of the moment and, for the most part, gran- Cdeur and ornamentation, too. Boldness, she believed, was a vice. Thirty years after her death, Head is getting a new dose of attention. A gor- geous coffee table book,Edith Head: The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood’s Greatest Costume Designer, was recently published. And in late March, an A to Z adapta- tion of Head’s seminal 1959 book, The Dress Doctor, is being released as well. ! The sTyle setter of The screen The breezy volume spotlights her trade- Clockwise from above: 1. -

Story/Clip English: Writing English: Reading Maths the Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson Pppc8w

Story/Clip English: Writing English: Reading Maths The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson Using descriptions from mouse to describe The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson Cooking: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s8sU the Gruffalo such as ‘He has terrible tusks, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s8sUPpPc8 Make some Purple Prickly pancakes. PpPc8Ws&t=222s (youtube) and terrible claws’ Can they label a picture Ws&t=222s Ingredients: of the Gruffalo? 200g self-raising flour Bear is not tired by Ciara Gavin 1 tbsp golden caster sugar Can you record yourself retelling the story https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HXfzj24mr 3 eggs of the Gruffalo? Maybe you could slither like H8 25g melted butter a snake or fly around like an owl? I would like 200ml milk to hear some animal noises, maybe small Hibernation station by Michelle Meadows Blueberries pitter patter for the mouse’s footsteps and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdbfXs1JbI https://www.bbcgoodfood.com/recipes/ame big heavy ones for the Gruffalo? Q rican-pancakes It is the Gruffalo’s birthday soon and he Snow rabbit, spring rabbit by Sung Na would like to invite his friends to his party. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tnr3eFdVC Can you write one invitation to one of his Z8 friends inviting them to his tea party in the woods? Phonic Bug: https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b The Hunt 00pk64x/the-gruffalo (BBC Short Choose a page from the book. Can you write Following the clues Movie) some speech bubbles for the characters? Rabbits What might they be saying to each other? https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/52153 Problem solving: 696 (Story about social distancing using If the Gruffalo saw 4 owls Monday and 2 on the Gruffalo characters) Tuesday. -

Classic Film Festival October 23-26

University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well Campus News Archive Campus News, Newsletters, and Events 8-19-2003 Classic Film Festival October 23-26 University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/urel_news Recommended Citation University Relations, "Classic Film Festival October 23-26" (2003). Campus News Archive. 1873. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/urel_news/1873 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Campus News, Newsletters, and Events at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campus News Archive by an authorized administrator of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contact Melissa Weber, Director of Communications Phone: 320-589-6414, [email protected] Jenna Ray, Editor/Writer Phone: 320-589-6068, [email protected] Classic Film Festival October 23-26 Summary: (August 19, 2003)-Discover a “classic” movie-viewing experience during the Morris Classic Film Festival to be held at the Morris Theatre October 23-26. The fifth annual Festival, sponsored by the Campus Activities Council Films Committee at the University of Minnesota, Morris, will again offer movies “as they were meant to be seen – on the big screen, in all their glory.” This year's lineup is another eclectic mix of classic films, from the raucous wit of Billy Wilder to the psychological complexity of Alfred Hitchcock. Here are the offerings: Thursday October 23 7pm - Funny Face (C,1957) Audrey Hepburn and Fred Astaire. A young woman agrees to model a line of ultra-chic fashions for a photographer so she can get to Paris to meet the beatnik founder of "empathicalism" (a rejection of all material things).