DRAWING COSTUMES, PORTRAYING CHARACTERS Costume Sketches and Costume Concept Art in the Filmmaking Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

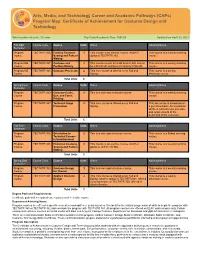

Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology

Arts, Media, and Technology Career and Academic Pathways (CAPs) Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology Total number of units: 23 units Top Code/Academic Plan: 1006.00 Updated on April 25, 2021 Fall Odd Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 366 Fantasy Costume 3 This course is an elective course. Another This course is a weekly morning Course Sewing and Pattern option is TECTHTR 365. course. Making Program/GE TECTHTR 367 Costume and 3 This course counts as a GE Area C Arts course This course is a weekly morning Course Fashion History for LACCD GE and Area C1 Arts for CSU GE. course. Program/GE TECTHTR 345 Costume Practicum 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This course is a weekly Course Spring. afternoon course. Total Units 8 Spring Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 363 Costume Crafts, 3 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a weekly morning Course Dye, and Fabric course. Printing Program TECTHTR 342 Technical Stage 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This lab course is scheduled on Course Production Spring. a per show basis. An orientation will be held to discuss schedule and requirements at the beginning of the semester. Total Units 5 Fall Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 305 Orientation to 2 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a Friday morning Course Technical Careers course. in Entertainment Program TECTHTR 365 Historical Costume 3 This course is an elective course. -

THTR 433A/ '16 CD II/ Syllabus-9.Pages

USCSchool of Costume Design II: THTR 433A Thurs. 2:00-4:50 Dramatic Arts Fall 2016 Location: Light Lab/PDE Instructor: Terry Ann Gordon Office: [email protected]/ floating office Office Hours: Thurs. 1:00-2:00: by appt/24 hr notice Contact Info: [email protected], 818-636-2729 Course Description and Overview This course is designed to acquaint students with the requirements, process and expectations for Film/TV Costume Designers, supervisors and crew. Emphasis will be placed on all aspects of the Costume process; Design, Prep: script analysis,“scene breakdown”, continuity, research, and budgeting; Shooting schedules, and wrap. The supporting/ancillary Costume Arts and Crafts will also be discussed. Students will gain an historical overview, researching a variety of designers processes, aesthetics and philosophies. Viewing films and film clips will support critique and class discussion. Projects focused on specific design styles and varied media will further support an overview of techniques and concepts. Current production procedures, vocabulary and technology will be covered. We will highlight those Production departments interacting closely with the Costume Department. Time permitting, extra-curricular programs will include rendering/drawing instruction, select field trips, and visiting TV/Film professionals. Students will be required to design a variety of projects structured to enhance their understanding of Film/TV production, concept, style and technique . Learning Objectives The course goal is for students to become familiar with the fundamentals of costume design for TV/Film. They will gain insight into the protocol and expectations required to succeed in this fast paced industry. We will touch on the multiple variations of production formats: Music Video, Tv: 4 camera vs episodic, Film, Commercials, Styling vs Costume Design. -

GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] +1(347)636.6681 AWARDS + HONORS SKILLS ASHLEY LAW EDUCATION WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL

ASHLEY LAW GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] http://ashleylaw.info +1(347)636.6681 linkedin.com/in/ashley-law instagram.com/_ashleylaw EDUCATION AWA RDS SKILLS SCHOOL OF VISUAL + GRAPHIS (GOLD) SOFTWARE ARTS (New York) NEW TALENT ANNUAL InDesign HONORS BFA Design Editorial Design “Zine”- Illustrator 2017–2019 2018 Photoshop PremierePro AfterEffects SCHOOL OF THE SVA HONOR’S LIST Sketch ART INSTITUTE OF 2017–2018 CHICAGO (Chicago) Fine Art + Visual CAPABILITIES & Critical Studies SAIC MERIT Branding 2013–2015 SCHOLARSHIP Content Production 2013–2015 Identity System Interactive/Digital Design Print + Editorial Design Typography WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL Junior Graphic Design for the GCL team focusing on CREATIVE LAB Designer creative direction of special projects, 06. 2019 - Present (New York) under the direction of Shu Hung and John Jay. Campaigns include collaborations (i.e. Lemaire, JW Anderson, Alexander Wang) and new store openings. MATTE PROJECTS Design Intern Designing client proposals, print, 01. 2019–04. 2019 (New York) digital & social collateral for marketing agency. Worked on projects for Cartier, The Chainsmokers, Moda Operandi & MATTE events (FNT, BLACK-NYC, Full Moon Festival, La Luna). PYT OPERANDI Creative Project Associate for artist management & creative 03–06. 2016 Associate project development company with emphasis (Hong Kong) in film, photography, exhibitions, project & business development consulting. CLOVER GROUP Intimates Design Designed for leading global manufacturer INTL LIMITED. Intern of intimate apparel, emphasis on the 08–10. 2015 (Hong Kong) Victoria’s Secret account. Visually detailed creative direction, identity & design of project pitches. Similar work for clients including Wacoal, Aerie, Lane Bryant. GIORGIO ARMANI Menswear R&D Shadowed Manager of R&D department OPERATIONS Intern for Menswear at HK Armani Corporate 06–09. -

Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association

For internal use only Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association. All rights reserved. Student(s): School: Selection: Troupe: 4 | Superior 3 | Excellent 2 | Good 1 | Fair SKILLS Above standard At standard Near standard Aspiring to standard SCORE Job Understanding Articulates a broad Articulates an Articulates a partial Articulates little and Interview understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the Articulation of the costume costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role designer’s role and specific and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; job responsibilities; thoroughly presents adequately presents and inconsistently presents does not explain an presentation and and explains the explains the executed and explains the executed executed design, creative explanation of the executed executed design, creative design, creative decisions, design, creative decisions decisions or collaborative design, creative decisions, decisions, and and collaborative process. and/or collaborative process. and collaborative process. collaborative process. process. Comment: Design, Research, A well-conceived set of Costume designs, Incomplete costume The costume designs, and Analysis costume designs, research, and script designs, research, and research, and analysis Design, research and detailed research, and analysis address the script analysis of the script do not analysis addresses the thorough script artistic and practical somewhat address the address the artistic and artistic and practical needs analysis clearly address needs of the production artistic and practical practical needs of the (given circumstances) of the artistic and practical and support the unifying needs of the production production or support the the script to support the needs of production and concept. -

Eiko Ishioka:Blood, Sweat, and Tears—A Life of Design

PRESS RELEASE 2020.6.30 The Tokyo Metropolitan Government and the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture are carrying out this exhibition as part of the Tokyo Tokyo FESTIVAL. Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo Eiko Ishioka: Blood, Sweat, and Tears—A Life of Design 14 November 2020 – 14 February 2021 The Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT) is pleased to present the world’s first large-scale retrospective exhibition dedicated to Eiko Ishioka (1938-2012), an internationally renowned art director and designer who ignited with her work a new era in various fields including advertising, theater, cinema, and graphic design. The exhibition takes a comprehensive look at Ishioka’s distinctive, incandescent creations, from her groundbreaking ad campaigns from early in her career, to her design work for films, opera, theater, circuses, music videos, and projects for the Olympic Games. Highlights Introducing Eiko Ishioka’s Design Process though Collaborations As described in detail in her autobiography, I DESIGN (Kodansha Ltd., 2005), Eiko Ishioka’s work has also been realized through a series of robust collaborations with great masters in their respective fields, such as Miles Davis, Leni Riefenstahl, Francis Ford Coppola, Björk, and Tarsem Singh. Along with extensive materials regarding her design process, the exhibition introduces and attempts to approach the secrets of “Eiko Ishioka’s Practice” which considers means of exerting individual creativity in the context of group production. Experience the Overwhelming Fervor of Eiko Ishioka’s Design This highly enthusiastic exhibition invites visitors to experience Eiko Ishioka’s works and her ongoing creations, which while harboring the vibrant dynamism of the human body at its core and focuses on “red” as a key color, have a great visual impact and exude emotion. -

Homage to Piero Tosi (Costume Designer)

The Scenographer presents Homage to Piero Tosi (costume designer) When I arrive at the Gino Carlo Sensani costume department accompanied by a student of the National School of Cinema, it does not in the least surprise me that Tosi receives me whilst keeping his back to me, intent on making some adjustment to a student’s problematic sketch. He pronounces a rapid greeting then lets pass a perfect lapse of time, neither too extended nor too brief, before turning to face me. Thoroughbred of the stage and screen, director of himself and in part an incorrigible actor, with an acknowledged debt to Norma Desmond and to those who still know how to descend a staircase with an outstretched arm on the banister, prompting those in attendance to take off their hat. I have known Pierino for many years, less in person, more through the words and the verbal accounts of Fellini, which almost never coincided with those of Tosi, yet traced a portrait with indelible colours. There is also a vague suggestion of witchcraft, from the moment in which the man ceased to change, neither from within nor from without. No sign of ageing, of the passing of time, preserved in a bubble of glass. Immutable, this is how Pierino Tosi appears to me, though he has no need of these compliments, neither does he fish for them, with always a foot placed on that shadowy line beyond which it is so easy to vanish, to fade away. Our mutual long-term acquaintance with Fellini draws us inevitably back to that climate. -

Master Class with Monique Prudhomme: Selected Bibliography

Master Class with Monique Prudhomme: Selected Bibliography The Higher Learning staff curate digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to guest speakers’ work and careers, and provide additional inspirations and topics to consider; these materials are meant to serve as a jumping-off point for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. Film Costume Design (History and Theory) Annas, Alicia. “The Photogenic Formula: Hairstyles and Makeup in Historical Style.” in Hollywood and History: Costume Design in Film. Edward Maeder (ed). Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1987. 52-77. Chierichetti, David, and Edith Head. Edith Head: The Life and Times of Hollywood's Celebrated Designer. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2003. Coppola, Francis Ford, Eiko Ishioka, and Susan Dworkin. Coppola and Eiko on Bram Stoker's Dracula. San Francisco: Collins Publishers, 1992. Gutner, Howard. Gowns by Adrian: The MGM Years 1928-1941. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001. Jorgensen, Jay. Edith Head: The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood's Greatest Costume Designer. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2010. Landis, Deborah N. Dressed: A Century of Hollywood Costume Design. New York: Collins Design, 2007. ---. Film Craft: Costume Design. New York: Focal Press, 2012. Laver, James, Amy De La Haye, and Andrew Tucker. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2002. Leese, Elizabeth. Costume Design in the Movies: An Illustrated Guide to the Work of 157 Great Designers. -

NATO Feb 05 NL.Indd

February 2005 NANATOTO of California/NevadaCalifornia/Nevada Information for the California and Nevada Motion Picture Theatre Industry THE CALIFORNIA POPCORN TAX CALENDAR By Duane Sharpe, Hutchinson and Bloodgood LLP of EVENTS & The California State Board of Equalization (the Board) recently issued an Opinion on a refund HOLIDAYS of sales tax to a local theatre chain (hereafter, the Theatre). The detail of the refund wasn’t discussed in the opinion, but the Board did focus on two specifi c issues that affected the refund. February 6 California tax law requires the assessment of sales tax on the sale of all food products when sold Super Bowl Sunday for consumption within a place that charges admission. The Board noted that in all but one loca- tion, the Theatre had changed their operations regarding admissions to its theatre buildings. Instead February 12 of requiring customers to fi rst purchase tickets to enter into the theatre building lobby in which all Lincoln’s Birthday food and drinks were sold, the Theatre opened each lobby to the general public without requiring tickets. The Theatre only required tickets for the customers to enter further into the inside movie February 14 viewing areas of the theatres. This admission policy allowed the Theatre not to charge sales tax on Valentine’s Day “popcorn sales.” California tax law requires the assessment of sales tax on the sale of “hot prepared food products.” The issue before the Board was whether the popcorn sold by the Theatre was a hot February 21 prepared food product. President’s Day From the Opinion: “Claimant’s process for making popcorn starts with a popper. -

THE FABRIC of DREAMS Master in Costume Design for Movies, TV and Stage

MDC MANIFATTURE DIGITALI CINEMA PRATO ASC ASSOCIAZIONE ITALIANA COSTUMISTI E SCENOGRAFI PIN POLO UNIVERSITARIO CITTA’ DI PRATO THE FABRIC OF DREAMS Master in Costume Design for Movies, TV and Stage 24 FEBRUARY – 2 MAY 2020 About the course The Italian tradition of Costume Design for Movies, TV and Stage structured as an intensive course taught by top Italian experts: Gabriella Pescucci, Carlo Poggioli and Alessandro Lai. “The Fabric of Dreams” Master in Costume Design for Movies, TV and Stage is an educational program for costume design. The aim is to offer a unique experience working with experts, exploring the history of costume through movies, interpreting historical costume as a means of designing contemporary costume, and making extraordinary garments with a view to opening a new museum. A top-tier program consisting of learning and hands-on experience under the guidance of leading professionals, expert craftspeople and internationally renowned companies. Tuscany has a history of thriving in the field of costume design, thanks to the first Grand Duke of Tuscany Cosimo I and his spouse Eleanor of Toledo, icons of the Florentine Renaissance. 500 hours, 64 days and a few weekends in which to learn to observe, design, cut, sew and organise. An intensive lab to achieve your dream to become a costume designer. The teachers Gabriella Pescucci, Carlo Poggioli and Alessandro Lai lead the course. Three renowned costume designers on the Italian and international film scene who vary in their styles and approaches, all conveying Italy’s exceptional flair for costume design. This course is their brainchild, an educational experience aimed at emerging professionals wishing to learn more about the theory and practice of costume design. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

HH Available Entries.Pages

Greetings! If Hollywood Heroines: The Most Influential Women in Film History sounds like a project you would like be involved with, whether on a small or large-scale level, I would love to have you on-board! Please look at the list of names below and send your top 3 choices in descending order to [email protected]. If you’re interested in writing more than one entry, please send me your top 5 choices. You’ll notice there are several women who will have a “D," “P," “W,” and/or “A" following their name which signals that they rightfully belong to more than one category. Due to the organization of the book, names have been placed in categories for which they have been most formally recognized, however, all their roles should be addressed in their individual entry. Each entry is brief, 1000 words (approximately 4 double-spaced pages) unless otherwise noted with an asterisk. Contributors receive full credit for any entry they write. Deadlines will be assigned throughout November and early December 2017. Please let me know if you have any questions and I’m excited to begin working with you! Sincerely, Laura Bauer Laura L. S. Bauer l 310.600.3610 Film Studies Editor, Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal Ph.D. Program l English Department l Claremont Graduate University Cross-reference Key ENTRIES STILL AVAILABLE Screenwriter - W Director - D as of 9/8/17 Producer - P Actor - A DIRECTORS Lois Weber (P, W, A) *1500 Major early Hollywood female director-screenwriter Penny Marshall (P, A) Big, A League of Their Own, Renaissance Man Martha -

Introduction

THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS THE OLIVE WONG PROJECT PERFORMANCE COSTUME DESIGN RESEARCH GUIDE INTRODUCTION COSTUME DESIGN AND PERFORMANCE WRITTEN AND EDITED BY AILEEN ABERCROMBIE The New York Public Library for the Perform- newspapers, sketches, lithographs, poster art ing Arts, located in Lincoln Center Plaza, is and photo- graphs. In this introduction, I will nestled between four of the most infuential share with you some of Olive’s selections from performing arts buildings in New York City: the NYPL collection. Avery Fisher Hall, Te Metropolitan Opera, the Vivian Beaumont Teater (home to the Lincoln There are typically two ways to discuss cos- Center Teater), and David H. Koch Teater. tume design: “manner of dress” and “the history Te library matches its illustrious location with of costume design”. “Manner of dress” contextu- one of the largest collections of material per- alizes the way people dress in their time period taining to the performing arts in the world. due to environment, gender, position, economic constraints and attitude. Tis is essentially the The library catalogs the history of the perform- anthropological approach to costume design. ing arts through collections acquired by notable Others study “the history of costume design”, photographers, directors, designers, perform- examining the way costume designers interpret ers, composers, and patrons. Here in NYC the the manner of dress in their time period: where so many artists live and work we have the history of the profession and the profession- an opportunity, through the library, to hear als. Tis discussion also talks about costume sound recording of early flms, to see shows designers’ backstory, their process, their that closed on Broadway years ago, and get to relationships and their work.