BBC Four Programme Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working-Class Cinema in the Age of Digital Capitalism

WORKING-CLASS CINEMA IN THE AGE OF DIGITAL CAPITALISM MASSIMILIANO MOLLONA he story of cinema starts with workers. The film Workers Leaving The TLumière Factory In Lyon (La Sortie des Usines Lumière à Lyon, 1895) by the brothers Louis and Auguste Lumière, 45 seconds long, shows the approximately 100 workers at a factory for photographic goods in Lyon- Montplaisir leaving through two gates and exiting the frame to both sides. But why does the story of cinema begin with the end of work? Is it because, as has been suggested, it is impossible to represent work from the perspective of labour but only from the point of view of capital, because the revolutionary horizon of the working class coincides with the end of work?1 After all, the early revolutionary art avant-garde had an ambiguous relationship with capitalism: it provided both a critique of commodification whilst also reproducing the commodity form.2 Even the cinema of Eisenstein, which so subverted the bourgeois sense of space, time, and personhood, at the same time standardized and commodified working-class reality with techniques of framing and editing that moulded images on the commodity form.3 Such dialectics between art and the commodity form continue to be played out in today’s digital capitalism, as exemplified by so-called ‘debt- artists’, like the hackers collective, Robin Hood, who appropriate the techniques and modes of sociality of financial capitalism to generate spaces of reciprocity and cooperation with the aim of disrupting their commodity logic, but which in fact end up reproducing it.4 The tension between critique and commodification is no less in play as the digital medium erases the specificity of cinema, the relation between its material bases and its poetics, opening up as it does to other relations – intertextual, lateral, and cross-media – that recall the synchronic aesthetics of the avant-garde. -

The Marie Curie Hospice, Cardiff and the Vale

Welcome to the Marie Curie Hospice, Cardiff and the Vale We’ve put together this folder with information about our hospice that you might find useful – such as the services we offer, how we can help and what you can expect from us. We want you to have a really comfortable stay with us, and get the most out of what we can offer. So just let us know if there’s anything that you need or something we can do for you, your family and your friends. You can always speak to your nurse if you have any questions or concerns about your care, or have any thoughts or suggestions about our hospice. We’re here to provide you, and those close to you, with our very best care and support. Paula Elson, Hospice Manager Marie Curie Hospice, Cardiff and the Vale Bridgeman Road, Penarth, Vale of Glamorgan CF64 3YR Reception: 02920 426 000 Ground floor ward: 02920 426 017 First floor ward: 02920 426 027 Email: [email protected] mariecurie.org.uk/cardiff Contents Your room 2 Food and drink 5 Medication 6 Information for your visitors 7 Preventing infections and how you can help 9 How to reduce your risk of falling 11 Our services and how we can help 12 Sources of information and other support for you 15 General information 16 How we keep your information safe and confidential 17 Let us know what you think 18 A little about Marie Curie 19 How you can support our work 21 List of TV channels and radio stations 22 Hospice information for in-patient care Page 1 Your room Your bed As your bed is adjustable, our nursing staff will explain to you how the bed’s control buttons work. -

How Do Film-Makers Manipulate Our Emotions with Music? by Helen Stewart BBC Arts & Culture

How do film-makers manipulate our emotions with music? By Helen Stewart BBC Arts & Culture In 1939, queen of Hollywood melodrama Bette Davis starred in Dark Victory - the tragic story of a wealthy party girl dying of a brain tumour. The audience knows that death will follow quickly after blindness. In the finale, her character's vision begins to falter and she moves slowly up a grand staircase. Davis knew this moment would secure her chance of a third Academy Award. She asked the director, "Who's scoring this film?" and was told it was the supremely talented Max Steiner. Steiner had composed the revolutionary score to King Kong in 1933. It was the first full Hollywood soundtrack, and one that allowed its fans to empathise with the fate of a plasticine gorilla. Davis was a clever woman. She understood the value of a soaring musical score, but feared its ability to outshine a performance. "Well," she declared, "either I am going up those stairs or Max Steiner is going up those stairs, but not the two of us together." Davis' opinion was ignored and two Oscar nominations were created in that scene. One for her and one for Steiner. It demonstrates the importance of music in film, and the power a soundtrack can have over audiences. Heightened senses Composer Neil Brand, presenter of BBC Four's The Music that Made the Movies, believes our senses are already heightened as we enter the cinema. "The darkness, the strangers, the anticipation, the warm comfortable embrace of the cinema seat. We're ready to experience some big emotions," he says, "and the minute the music booms out, we are on board for the ride. -

BF1 / LSO Artwork 05/05/2016 12:22 Page 1

BF03_2016SymphCity_AW:BF1 / LSO artwork 05/05/2016 12:22 Page 1 Brighton: Symphony of a City World Premiere Commissioned by Brighton Festival Brighton Festival music supported by Supported by Screen Archive South East, University of Brighton and University of Sussex The Steinway concert piano chosen and hired by Brighton Festival for this performance is supplied and maintained by Steinway & Sons, London Wed 11 May, 7.30pm Brighton Dome Concert Hall Brighton Festival programmes are supported by West Sussex Print Limited Please ensure that all mobile phones are switched off BF03_2016SymphCity_AW:BF1 / LSO artwork 05/05/2016 12:22 Page 2 Brighton: Symphony of a City Part 1 Film Film director Lizzie Thynne Editor Phil Reynolds Associate film producer Catalina Balan Music Composer and conductor Ed Hughes Orchestra of Sound and Light producer Liz Webb Orchestra leader Christina Woods Live score performed by Orchestra of Sound and Light Seafront woman with phone Jessica Griffin Couple at Waterstones Georgia Rooney, Kate Ballard Couple at telescope Ingvild Deila, Ian Habgood Puppetry artists Sam Toft, Kate James Moore Aya Nakamura and Mohsen Nouri Touched Theatre Circus ‘Flown’, Pirates of the Carabina, Brighton Dome Cabaret Rubyyy Jones Camera Catalina Balan Lizzie Thynne Additional camera John Hondros, Lee Salter, Yue Lia, Xilun Li, Pui Yu Taw, Jessica Chan, Liuyun Zhang Colourist Neil Whitehead Archive Screen Archive South East, University of Brighton: ‘Southern Railway’, 1937–8, Eric Sparks, by kind permission of Mr R. Bamberough ‘Father Neptune’ -

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Café Society

Presents CAFÉ SOCIETY A film by Woody Allen (96 min., USA, 2016) Language: English Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia CAFÉ SOCIETY Starring (in alphabetical order) Rose JEANNIE BERLIN Phil STEVE CARELL Bobby JESSE EISENBERG Veronica BLAKE LIVELY Rad PARKER POSEY Vonnie KRISTEN STEWART Ben COREY STOLL Marty KEN STOTT Co-starring (in alphabetical order) Candy ANNA CAMP Leonard STEPHEN KUNKEN Evelyn SARI LENNICK Steve PAUL SCHNEIDER Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON, p.g.a. STEPHEN TENENBAUM, p.g.a. EDWARD WALSON, p.g.a. Co-Producer HELEN ROBIN Executive Producers ADAM B. STERN MARC I. STERN Executive Producer RONALD L. CHEZ Cinematographer VITTORIO STORARO AIC, ASC Production Designer SANTO LOQUASTO Editor ALISA LEPSELTER ACE Costume Design SUZY BENZINGER Casting JULIET TAYLOR PATRICIA DiCERTO 2 CAFÉ SOCIETY Synopsis Set in the 1930s, Woody Allen’s bittersweet romance CAFÉ SOCIETY follows Bronx-born Bobby Dorfman (Jesse Eisenberg) to Hollywood, where he falls in love, and back to New York, where he is swept up in the vibrant world of high society nightclub life. Centering on events in the lives of Bobby’s colorful Bronx family, the film is a glittering valentine to the movie stars, socialites, playboys, debutantes, politicians, and gangsters who epitomized the excitement and glamour of the age. Bobby’s family features his relentlessly bickering parents Rose (Jeannie Berlin) and Marty (Ken Stott), his casually amoral gangster brother Ben (Corey Stoll); his good-hearted teacher sister Evelyn (Sari Lennick), and her egghead husband Leonard (Stephen Kunken). -

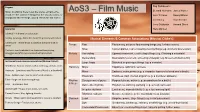

Knowledge Organiser

Key Composers Purpose Bernard Hermann James Horner Music in a film is there to set the scene, enhance the AoS3 – Film Music mood, tell the audience things that the visuals cannot, or John Williams Danny Elfman manipulate their feelings. Sound effects are not music! John Barry Alan Silvestri Jerry Goldsmith Howard Shore Key terms Hans Zimmer Leitmotif – A theme for a character Mickey-mousing – When the music fits precisely with action Musical Elements & Common Associations (Musical Cliche’s) Underscore – where music is played at the same time as action Tempo Fast Excitement, action or fast-moving things (eg. A chase scene) Slow Contemplation, rest or slowing-moving things (eg. A funeral procession) Fanfare – short melodies from brass sections playing arpeggios and often accompanied with percussion Melody Ascending Upward movement, or a feeling of hope (eg. Climbing a mountain) Descending Downward movement, or feeling of despair (eg. Movement down a hill) Instruments and common associations (Musical Clichés) Large leaps Distorted or grotesque things (eg. a monster) Woodwind - Natural sounds such as bird song, animals, rivers Harmony Major Happiness, optimism, success Bassoons – Sometimes used for comic effect (i.e. a drunkard) Minor Sadness, seriousness (e.g. a character learns of a loved one’s death) Brass - Soldiers, war, royalty, ceremonial occasions Dissonant Scariness, pain, mental anguish (e.g. a murderer appears) Tuba – Large and slow moving things Rhythm Strong sense of pulse Purposefulness, action (e.g. preparations for a battle) & Metre Harp – Tenderness, love Dance-like rhythms Playfulness, dancing, partying (e.g. a medieval feast) Glockenspiel – Magic, music boxes, fairy tales Irregular rhythms Excitement, unpredictability (e.g. -

Graham Walker Film Music Producer / Music Production Supervisor

GRAHAM WALKER FILM MUSIC PRODUCER / MUSIC PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR Graham is one of Britain’s most experienced and active Music Producers specialising in the international film music business. Education Graham studied music at Kneller Hall, the Royal Military School of Music and the Guildhall School of Music in London after which he began his career in the music production business. Graham is also a good musician; a trumpet player. Graham is one of Britain’s most experienced and active Music Producers specialising in the international film music business. After a distinguished career as Musical Director of Yorkshire Television, Head of Music for Granada Television and Head of Film Music Production for Lord Grade’s ITC Films, Graham then became freelance. The first 6 years of Graham’s career were spent at the world famous KPM Production Music Library; that was the day job! The night job was arranging and conducting sessions for various ‘pop’ and variety stars’ singles and albums such as Dickie Henderson, Roy Castle, Nicko McBrain (the drummer from Iron Maiden) and the number 1 hit ‘Grandad’ performed by Clive Dunn(!) plus score takedowns for the BBC’s ‘Top of the Pops’ for US groups such as ‘The Four Tops,’ Diana Ross and The Supremes,’ Otis Redding,’ ‘Marvin Gaye’ and many others. Work: Musical Director - Yorkshire Television, Head of Music - Granada Television, Head of Film Production (Music) - Lord Grade’s ITC Films, Head of Music - Zenith Productions. Over the years Graham has acquired extensive expertise in recording throughout Europe and beyond. He has worked with many composers, musicians and orchestras in the recording centres of London, New York, Paris, Munich, Cologne, Rome, Brussels, Berlin, Budapest, Moscow, Belgrade, Prague, Bratislava, Brandenburg and various locations in South Africa. -

The Commutation Test and Chris Bacon's Score for Source Code As

The Commutation Test and Chris Bacon’s Score for Source Code as a Framework for Film Music Pedagogy Aaron Ziegel, Towson University he cinema, whether experienced at the neighborhood multiplex or streamed at home, is arguably the medium through which today’s col- lege-age Americans are most likely to encounter newly composed sym- Tphonic music. Given the ubiquity of the film-viewing experience, students are often eager to learn the tools and methodologies that can equip them to criti- cally assess and more fully comprehend the function of music in movies. The filmSource Code (2011), directed by Duncan Jones and scored by Chris Bacon, provides a particularly effective starting point through which this process can begin.1 This article will discuss the pedagogical potential found in the film’s main titles and the impact of applying a commutation test to this sequence. Although here I address one specific example, the methodology of the commu- tation test is easily adaptable to other circumstances, as the theoretical foun- dation will make clear. While variations on the commutation test are a regular occurrence in many film music classrooms, this essay aims to present an intro- ductory primer that may be of use to instructors interested in an entry point for incorporating film music studies into their teaching. With that in mind, the appendix presents one suggestion for how to create film clips for classroom use. The value of this classroom activity extends beyond providing students with an engaging and memorable learning experience. By situating this analysis I wish to express my gratitude to the many students at Towson University whose feedback and enthusiastic classroom participation, along with suggestions from the anonymous reviewers, helped me to refine the pedagogical approach described in this essay.