Film Music, Serious Or Tourist, Should Begin Right Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

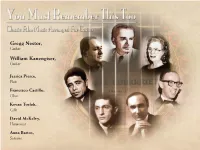

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

Film Theme Music Calendar for May 2020

ListeningMA CalendarY 2020 May 2020 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT A Gift of a Thistle Anakin's Theme 1 From Braveheart 2 from By John by James Horner Williams Elevator to the Interstellar Main Theme from Schindler's List The Heart Asks The Mask of Kiss the Girl 3 Gallows by Miles 4 Theme by Hans 5 James Bond by 6 by John Williams 7 Pleasure From 8 Zorro by James 9 from The Little Davis Zimmer David Arnold The Piano by Horner Mermaid by Michael Nyman Samuel Wright Hymn to the Fallen Married Life Apollo 13 by Gabriel's Oboe Thor: The Dark Friend Like Me Jake's First Flight From from Saving Private from Up by James Horner from The Mission World from from Aladdin by 10 Ryan by John 11 12 13 14 15 16 Avatar by Michael by Enrico Thor by Brian Alan Menken Williams James Horner Giacchino Morricone Tyler Theme from The Shallow from A Main Theme from Moon River from Axel Foley from Feather Theme Black Hills of Godfather by Star is Born by The Man From Breakfast at Beverly Hills Cop from Forrest Dakota from 17 18 19 20 Tiffany's by 21 by Harold 22 23 Nino Rota Lady Gaga Snowy River by Gump by Alan Calamity Jame by Henry Mancini Faltermeyer Bruce Rowland Silvestri from Sammy Fain Somewhere over Ben Hur by The Hanging Tree Welcome to The Exorcist Psycho by The Lonley the Rainbow from Miklos Rozsa from The Hunger Jurrasic Park by Theme by Mike Shepherd from Kill 24 25 26 27 The Wizard of Oz 28 29 Bernard 30 Games by James John Williams Bill by Gheorghe by Harold Arlen Oldfield Herrmann Newton Howard Zamfir End Theme from Dances with 31 Wolves by John Barry Holidays and Observances: 5: Cinco de Mayo, 10: Mother's Day, 25: Memorial Day www.wiki-calendar.com. -

An Examination of Jerry Goldsmith's

THE FORBIDDEN ZONE, ESCAPING EARTH AND TONALITY: AN EXAMINATION OF JERRY GOLDSMITH’S TWELVE-TONE SCORE FOR PLANET OF THE APES VINCENT GASSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY 2019 © VINCENT GASSI, 2019 ii ABSTRACT Jerry GoldsMith’s twelve-tone score for Planet of the Apes (1968) stands apart in Hollywood’s long history of tonal scores. His extensive use of tone rows and permutations throughout the entire score helped to create the diegetic world so integral to the success of the filM. GoldsMith’s formative years prior to 1967–his training and day to day experience of writing Music for draMatic situations—were critical factors in preparing hiM to meet this challenge. A review of the research on music and eMotion, together with an analysis of GoldsMith’s methods, shows how, in 1967, he was able to create an expressive twelve-tone score which supported the narrative of the filM. The score for Planet of the Apes Marks a pivotal moment in an industry with a long-standing bias toward modernist music. iii For Mary and Bruno Gassi. The gift of music you passed on was a game-changer. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Heartfelt thanks and much love go to my aMazing wife Alison and our awesome children, Daniela, Vince Jr., and Shira, without whose unending patience and encourageMent I could do nothing. I aM ever grateful to my brother Carmen Gassi, not only for introducing me to the music of Jerry GoldsMith, but also for our ongoing conversations over the years about filM music, composers, and composition in general; I’ve learned so much. -

Your Concert Guide

silver screen sounds your concert guide EDEN COURT caird hall tramway the queen's hall INVERNESS dundee glasgow edinburgh 10 Sep 14 Sep 15 Sep 16 Sep welcome to silver screen sounds Over the course of the concert, you'll hear music chosen to accompany films and extracts from scores written specifically for the screen. There'll be pauses between some, and others will flow into the next. We recommend following along with your listings insert, and using this guide as extra reading. 1 by Bernard Herrmann Prelude from Psycho psycho (1960) Directed by Alfred Hitchcock "When a director finds a composer who understands them, who can get inside their head, who can second-guess them correctly, they're just going to want to stick with that person. And Psycho... it was just one of these absolute instant connections of perfect union of music and image, and Hitchcock at his best, and Bernard Herrmann at his best." Film composer Danny Elfman Herrmann's now-equally-iconic soundtrack to Hitchcock's iconic film showed generations of filmmakers to come the power that music could have. It's a rare example of a film score composed for strings only, a restriction of tonal colour that was, according to an interview with Herrmann, intended as the musical equivalent of Hitchcock's choice of black and white (Hitchcock had originally requested a jazz score, as well as for the shower scene to be silent; Herrmann clearly decided he knew better). Also known as the 'Psycho theme', this prelude is frenetic and fast-paced, suggesting flight and pursuit. -

Adventures in Film Music Redux Composer Profiles

Adventures in Film Music Redux - Composer Profiles ADVENTURES IN FILM MUSIC REDUX COMPOSER PROFILES A. R. RAHMAN Elizabeth: The Golden Age A.R. Rahman, in full Allah Rakha Rahman, original name A.S. Dileep Kumar, (born January 6, 1966, Madras [now Chennai], India), Indian composer whose extensive body of work for film and stage earned him the nickname “the Mozart of Madras.” Rahman continued his work for the screen, scoring films for Bollywood and, increasingly, Hollywood. He contributed a song to the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006) and co- wrote the score for Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007). However, his true breakthrough to Western audiences came with Danny Boyle’s rags-to-riches saga Slumdog Millionaire (2008). Rahman’s score, which captured the frenzied pace of life in Mumbai’s underclass, dominated the awards circuit in 2009. He collected a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for best music as well as a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for best score. He also won the Academy Award for best song for “Jai Ho,” a Latin-infused dance track that accompanied the film’s closing Bollywood-style dance number. Rahman’s streak continued at the Grammy Awards in 2010, where he collected the prize for best soundtrack and “Jai Ho” was again honoured as best song appearing on a soundtrack. Rahman’s later notable scores included those for the films 127 Hours (2010)—for which he received another Academy Award nomination—and the Hindi-language movies Rockstar (2011), Raanjhanaa (2013), Highway (2014), and Beyond the Clouds (2017). -

Biography: 850 Words)

Sara Davis Buechner (long biography: 850 words) Sara Davis Buechner is one of the leading concert pianists of our time. She has been praised worldwide as a musician of “intelligence, integrity and all- encompassing technical prowess” (New York Times); lauded for her “fascinating and astounding virtuosity” (Philippine Star), and her “thoughtful artistry in the full service of music” (Washington Post); and celebrated for her performances which are “never less than 100% committed and breathtaking” (Pianoforte Magazine, London). Japan’s InTune magazine says: “When it comes to clarity, flawless tempo selection, phrasing and precise control of timbre, Buechner has no superior.” In her twenties, Ms. Buechner was the winner of a bouquet of prizes at the world’s première piano competitions -- Queen Elisabeth of Belgium, Leeds, Salzburg, Sydney and Vienna. She won the Gold Medal at the 1984 Gina Bachauer International Piano Competition, and was a Bronze Medalist of the 1986 Tschaikowsky International Piano Competition in Moscow. With an active repertoire of more than 100 piano concertos ranging from A (Albeníz) to Z (Zimbalist) -- one of the largest of any concert pianist today -- she has appeared as soloist with many of the world’s prominent orchestras: New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Saint Louis, San Francisco, Montréal, Edmonton, Vancouver, Victoria, Honolulu, Qingdao and Tokyo; the CBC Radio Orchestra, Japan Philharmonic, City of Birmingham (U.K.) Symphony Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic, Moscow Radio Symphony, Kuopio (Finland) Philharmonic, Slovak Philharmonic and the Orquesta Sinfónica de Castilla y León (Spain). Audiences throughout North America have applauded Ms. Buechner’s recitals in venues such as Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Kennedy Center and the Hollywood Bowl; and she enjoys wide success throughout Asia where she tours annually. -

Download the Digital Booklet

ELMER BERNSTEIN NICHOLAS BRITELL 01 World Soundtrack Awards Fanfare 1:33 09 Succession (Suite) 4:25 JAMES NEWTON HOWARD MYCHAEL DANNA 02 Red Sparrow Overture 6:36 10 Monsoon Wedding (Suite) 3:15 CARTER BURWELL ALEXANDRE DESPLAT 03 Fear - Main Title 2:32 11 The Imitation Game (Suite) 4:33 ALBERTO IGLESIAS PATRICK DOYLE 04 Hable con ella - Soy Marco 2:17 12 Murder on the Orient Express - Never Forget (Instrumental Version) 4:12 ELLIOT GOLDENTHAL 05 Cobb - The Homecoming 6:16 MICHAEL GIACCHINO 13 Star Trek, into Darkness and Beyond (Suite) 7:23 GABRIEL YARED 06 Troy (Suite) 5:19 ANGELO BADALAMENTI 14 Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me - JÓHANN JÓHANNSSON / The Voice of Love 4:02 RUTGER HOEDEMAEKERS 07 When at Last the Wind Lulled 2:13 JOHN WILLIAMS (Arr.) 15 Tribute to the Film Composer 4:25 JOHN WILLIAMS 08 Hook - The Face of Pan 4:06 Performed by BRUSSELS PHILHARMONIC & VLAAMS RADIOKOOR Conducted by DIRK BROSSÉ TWENTY YEARS OF WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARDS Twenty years ago the World Soundtrack Academy scores achieved an afterlife and gained new handed out the very first World Soundtrack meaning as the result of live performances in Awards. They have since become of paramount front of audiences. Film Fest Ghent has made it importance across the industry. The awards did their point of honour to perpetuate that afterlife not only strengthen Film Fest Ghent’s identity, in Ghent in a series of albums. they have been a composer’s stepping stone to the Oscars, Golden Globes and BAFTAS. If To celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Europe is now the metropolis of film music, then WSA, the album consists of compositions by Ghent has been the inspiration for it. -

The City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus

SPRING 2016 NEWS www.tadlowmusic.com THE CITY OF PRAGUE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA AND CHORUS EUROPE’S MOST EXPERIENCED AND VERSATILE RECORDING ORCHESTRA: 70 YEARS OF QUALITY MUSIC MAKING The CoPPO have been recording local film and TV scores at Smecky Music Studios since 1946, and a large number of international productions since 1988. Over the years they have worked with many famous composers from Europe and America including: ELMER BERNSTEN * MICHEL LEGRAND * ANGELO BADALAMENTI * WOJCIECH KILAR * CARL DAVIS GABRIEL YARED * BRIAN TYLER * RACHEL PORTMAN * MYCHAEL DANNA * JEFF DANNA * NITIN SAWHNEY JAVIER NAVARRETE * LUDOVIC BOURCE * CHRISTOPHER GUNNING * INON ZUR * JOHANN JOHANNSSON * NATHANIEL MECHALY * PATRICK DOYLE In recent years they have continued this tradition of recording orchestral scores for international productions with composers now recording in Prague from: Australia * New Zealand * Japan * Indonesia * Malaysia * Singapore * China * Taiwan * Russia * Egypt * The Lebanon * Turkey * Brazil * Chile and India Prague has become the centre for worldwide scoring. COST OF 100% TOTAL BUYOUT RECORDING IN PRAGUE (DUE TO EXCHANGE RATE CHANGES) IS EVEN MORE FAVOURABLE THAN IT WAS 5 YEARS AGO ! TADLOW MUSIC The Complete Recording Package for FILM, TV, VIDEO GAMES SCORING AND FOR THE RECORD INDUSTRY in LONDON + PRAGUE Music Contractor / Producer : James Fitzpatrick imdb page: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0280533/ NEW PHONE # : +44 (0) 797 181 4674 “It’s an absolute delight to work with Tadlow Music. The Prague musicians are great and I’ve had many happy experiences recording with them.” - Oscar Winning Composer RACHEL PORTMAN “Always a pleasure to work with James, as i have many times over the years. -

This Is a Course Designed for Upper-Level Students. It

1 FA 483 Special Topics: Film Scores: Meaning and Music in Cinema Ufuk Çakmak Department of Western Languages an Literatures TTT 678 THIS IS A COURSE DESIGNED FOR UPPER-LEVEL STUDENTS. IT REQUIRES HARD-WORK, A GOOD DEAL OF INTERPRETATIVE CAPACITY, A REAL CURIOSITY TOWARDS THE GREAT MASTERS OF CINEMA AND FILM MUSIC. IF YOU ARE LOOKING FOR A LIGHT COURSE, DON’T TAKE THIS COURSE. NO BOX-OFFICE, COMMERCIAL FILMS. NOT SUITABLE FOR FIRST THREE SEMESTER STUDENTS. Course Description This is a course in film music and cinematic meaning, an attempt to understand creation of meaning through music on the silver screen. Because of its very nature, the course involves two different genres of art: music and cinema. This makes it heavier in course work, as the number of items to be covered multiply by two. You will have screening homeworks on one side where you will screen whole films in their entirety or evaluate excerpts, and you will have pure listening homeworks on the other side, on albums and tracks. You will be requested to write short and/or long response papers on assignments. Although, the course is entitled “Film Scores”, it does not discriminate other meaning formative elements of cinema, and aims at a holistic understanding of the films it tackles. Therefore, you shouldn’t expect a course in pure music. This is a course in both cinema and music. The films I dwell are not commercially oriented, box office films. I’m interested in works of art that search for a profound meaning in an existential journey. -

Steve Fogleman Thesis

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: ________________________________ _____________ Stephen Fogleman Date The Rózsa Touch: Challenging Classical Hollywood Norms Through Music By Stephen Fogleman Master of Arts Film Studies ____________________________________ Matthew H. Bernstein, Ph.D. Advisor ____________________________________ Karla Oeler, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________________ Michele Schreiber, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: ____________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ____________________________________ Date The Rózsa Touch: Challenging Classical Hollywood Norms through Music By Stephen Fogleman B.A. Appalachian State University, 2009 Advisor: Matthew H. Bernstein, Ph.D. An abstract of A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies 2011 Abstract The Rózsa Touch: Challenging Classical Hollywood Norms through Music By Stephen Fogleman If film noir is a body of work that is partially characterized by its difference from other Classical Hollywood films, many of the scores for these films work to reinforce that difference.