A R C R E E L M U S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genre Album Artist and Title Avantgarde Various - Linn SACD Sampler Various - Stay in Tune with Pentatone

Genre Album Artist and Title Avantgarde Various - Linn SACD Sampler Various - Stay in Tune with PentaTone Bluegrass Nickel Creek - This Side Nickel Creek - Nickel Creek Christmas Bach Collegium Japan - Verbum caro factum est Choir of St John's College, Cambridge/Challenger/Nethsingha - On Christmas Night Elena Fink, Le Quatuor Romantique - A Late Romantic Christmas Eve Le Quatuor Romantique - A Late Romantic Christmas Eve Oscar's Motet Choir - Cantate Domino Stile Antico - Puer natus est: Music for Advent and Christmas - Stile Antico Vox Aurea, Sanna Salminen - Matkalla jouluun / A Journey into Christmas Classical Aachen Symphony, Vocapella Choir - Verdi Missa da Requiem Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Marriner - Mozart: Clarinet Concert in A, KV 622 , Clarinet Quintet in A, KV 581 Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Marriner - The Art of the Fugue Angela Hewitt, ACO - Bach Keyboard Concertos Vol 2 Angela Hewitt, ACO - Bach Keyboard Concertos Vol1 Angela Hewitt, piano - J.-P Rameau: Suites Artur Pizarro - Chopin Piano Sonatas Artur Pizarro - Frederic Chopin Artur Pizarro, Scottish Chamber Orchestra - Beethoven Piano Concerto No.5 Artur Pizarro, Scottish Chamber Orchestra - Beethoven Piano Concertos No.3 & No.4 Atlanta Symphony Orchestra - Vaughan Williams: A Sea Symphony Brendel, SCO, Mackerras - Mozart: Piano Concertos K271 & K503 Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, Kunzel - A Celtic Spectacular Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, Kunzel - Tchaikovsky 1812 Donald Runnicles, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus - Orff: Carmina Burana Dunedin Consort -

Indian and Polish Film Festivals

Indian and Polish film festivals articles.latimes.com /2009/apr/16/entertainment/et-screening16 New films from India and Poland are highlighted in the seventh annual Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles and the 10th Polish Film Festival. The Indian Film Festival, which runs Tuesday through April 26, includes five feature films making their world premiere, five making their U.S. premiere and another five making their L.A. debut. The festivities begin with the world premiere of Anand Surapar's "The Fakir of Venice" at the ArcLight Hollywood Cinemas. Ani Kapoor of "Slumdog Millionaire" will also be saluted during the festival with screenings of two of his classic films and the premiere of the English-language version of 2007's "Gandhi, My Father," which he produced. www.indianfilmfestival.org The Polish Film Festival has its gala opening Wednesday at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood with a screening of "Perfect Guy for My Girl." It continues through May 3 at Laemmle's Sunset 5 Theatre and other venues in Los Angeles and Orange counties. www .polishfilmla.org -- French composers Two of the late Maurice Jarre's great scores -- for 1985's "Witness" and 1986's "The Mosquito Coast" -- are featured in the American Cinemathque's weekend retrospective "The French Music Composers Go to Hollywood" at the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica. The beautiful music begins tonight with a double bill of 1981's "Woman Next Door," composed by Georges Delerue, and 2001's "Read My Lips," scored by Alexandre Desplat. Michel Legrand supplied the score for 1968's "The Thomas Crown Affair," screening Friday with Michel Colombier's score for 1984's "Against All Odds." The Jarre double feature is scheduled for Saturday. -

Academy Committees 19~5 - 19~6

ACADEMY COMMITTEES 19~5 - 19~6 Jean Hersholt, president and Margaret Gledhill, Executive Secretary, ex officio members of all committees. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE SPECIAL DOCUMENTARY Harry Brand COMMITTEE lBTH AWARDS will i am Do z i e r Sidney Solow, Chairman Ray Heindorf William Dozier Frank Lloyd Philip Dunne Mary C. McCall, Jr. James Wong Howe Thomas T. Moulton Nunnally Johnson James Stewart William Cameron Menzies Harriet Parsons FINANCE COMMITTEE Anne Revere Joseph Si strom John LeRoy Johnston, Chairman Frank Tuttle Gordon Hollingshead wi a rd I h n en · SPECIAL COMMITTEE 18TH AWARDS PRESENTATION FILM VIEWING COMMITTEE Farciot Edouart, Chairman William Dozier, Chairman Charles Brackett Joan Harrison Will i am Do z i e r Howard Koch Hal E1 ias Dore Schary A. Arnold Gillespie Johnny Green SHORT SUBJECTS EXECUTIVE Bernard Herzbrun COMMI TTEE Gordon Hollingshead Wiard Ihnen Jules white, Chairman John LeRoy Johnston Gordon Ho11 ingshead St acy Keach Walter Lantz Hal Kern Louis Notarius Robert Lees Pete Smith Fred MacMu rray Mary C. McCall, Jr. MUSIC BRANCH EXECUTIVE Lou i s Mesenkop COMMITTEE Victor Milner Thomas T. Moulton Mario Caste1nuovo-Tedesco Clem Portman Adolph Deutsch Fred Ri chards Ray Heindorf Frederick Rinaldo Louis Lipstone Sidney Solow Abe Meyer Alfred Newman Herbert Stothart INTERNATIONAL AWARD Ned Washington COMM I TTEE Charles Boyer MUSIC BRANCH HOLLYWOOD Walt Disney BOWL CONCERT COMMITTEE wi 11 i am Gordon Luigi Luraschi Johnny Green, Chairman Robert Riskin Adolph Deutsch Carl Schaefer Ray Heindorf Robert Vogel Edward B. Powell Morris Stoloff Charles Wolcott ACADEMY FOUNDATION TRUSTEES Victor Young Charles Brackett Michael Curtiz MUSIC BRANCH ACTIVITIES Farc i ot Edouart COMMITTEE Nat Finston Jean Hersholt Franz Waxman, Chairman Y. -

23 a 30 De Março Programa

SEMANA DO PIANO 23 a 30 de março programa 23 e 24 de março Masterclasse Luís Pipa Local: Conservatório de Música Calouste Gulbenkian de Braga A S e m a n a d o Pi a n o é u m a at i v i d a d e Os Concertos com Artur Pizarro e Pedro 25 e 26 de março desenvolvida numa parceria entre a Câmara Burmester trazem à cidade de Braga duas das Concurso Regional de Piano Local: Conservatório de Música Calouste Gulbenkian de Braga Municipal de Braga (CMB), pelouro da cultura, e maiores referências do piano em Portugal. O * 25 março | 21.30 horas o Conservatório de Música Calouste Gulbenkian concerto do Bruno Ferreira é o encontro Concerto Piano, Artur Pizarro de Braga (CMCGB), cujo objetivo é celebrar e marcado com um jovem talento, que foi prémio Local: Auditório Vita. Obras de: Chopin, Schumann; José Vianna da Motta, colocar o Piano no centro da atenção da cidade Conservatório na sua edição de 2014/15. Luís Costa e Claudio Carneyro. num convite à fruição de momentos excelentes A componente pedagógica, desta atividade, Entrada: 5 euros. para todos. convida os alunos de Música a usufruírem da 27 de março | 19 horas À volta do Piano Day, dia celebrado em todo o master classe do prof. Luís Pipa, que decorre Concerto Jovem talento- Piano, Bruno Ferreira prémio Conservatório ed. 2014-15. mundo ao 88º dia do ano, coincidindo com as 88 nos dois primeiros dias da semana do piano, e a Local: Conservatório de Música Calouste Gulbenkian de Braga Obras: R. -

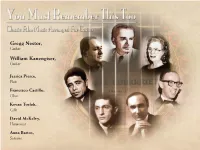

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Maurice Jarre Almost an Angel Mp3, Flac, Wma

Maurice Jarre Almost An Angel mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop / Classical / Stage & Screen Album: Almost An Angel Country: US Released: 1990 Style: Score, Neo-Classical, Ballad MP3 version RAR size: 1908 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1250 mb WMA version RAR size: 1436 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 352 Other Formats: MP2 WMA MP1 APE DXD DTS VOC Tracklist Hide Credits Some Wings A1 –Vanessa Williams Lyrics By – Ray UnderwoodMusic By – Maurice JarreRecorded By [Vocals] – Jerry Brown* A2 –Maurice Jarre Almost An Angel A3 –Maurice Jarre Fly A4 –Maurice Jarre Rose And Terry The Mafia Bluff B1 –Maurice Jarre Composed By [Contains Love Theme From The Godfather] – Nino Rota B2 –Maurice Jarre Steve's Run B3 –Maurice Jarre Let There Be Light Credits Composed By, Conductor – Maurice Jarre Contractor, Coordinator [Music] – Leslie Morris Edited By [Digitally] – Dave Collins Executive-Producer – Robert Townson Liner Notes – John Cornell Mixed By – Shawn Murphy Mixed By [Assisted By] – Sharon Rice Other [Assistant To Maurice Jarre] – Pat Russ Producer – Maurice Jarre Recorded By [Music] – Robert Fernandez, Shawn Murphy Supervised By [Production Supervisor] – Tom Null Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 30206-5307-4 2 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Almost An Angel (Original Maurice Varèse VSD-5307 Motion Picture Soundtrack) VSD-5307 US 1990 Jarre Sarabande (CD, Album) Almost An Angel (Original Maurice Varèse VS-5307 Motion Picture Soundtrack) VS-5307 Germany 1990 Jarre Sarabande (LP, Album) Maurice -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

Roach and Barker Are Elected President, Vice-President Of

VOLUME XLV VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE, LEXINGTON, VIRGINIA, JANUARY 17, 1955 NUMBER 14 Eugene List^ Famous Pianist Two '53 Grads Roach And Barker Are Elected To Concertize In Lexington To Be Air Tacs Two 1953 graduates of Virginia President, Vice-President Of OGA For Rockbridge Concert Series Military Institute have been select- ed for duty on the tactical staff Last Tuesday evening, immediately following the Corps One of the most widely Itnown' of the new Air Force Academy, Meeting, the Officer of the Guard Association met for the and praised of American pianists On Lee's Birthday according to an announcen\ent by is young Eugene List, who accord- purpose of electing new officers. Bill Maddox, the Retiring Colonel Robert M. Stillman, Air ing to international critical ac- Seven score to an added eight President, announced his decision to relinquish his position Force Academy Commandant. claim, is destined for music's per- Years bence, was upon this date, because of his desire to apply him- manent "Who's Who." He will ap- They are Lieutenants Harry C. A Virginian bom on the creat of self more diligently to his studies. pear here in concert on February Gornto, HI, of Norfolk, and Charles fate. Law Would Deepen "Basically, we hope to have the R. Steward, of Coolidge, Ariz., both 3 at Lexington High School unde^ The South has cause to same objectives as before: first of- of whom entered the Air Force the auspeces of the Rockbridge commemmrate. all, to enforce the Class System; pilot training program following Army Reserves Concert Series. -

Listening to Movies: Film Music and the American Composer Charles Elliston Long Middle School INTRODUCTION I Entered College

Listening to Movies: Film Music and the American Composer Charles Elliston Long Middle School INTRODUCTION I entered college a naïve 18-year-old musician. I had played guitar for roughly four years and was determined to be the next great Texas blues guitarist. However, I was now in college and taking the standard freshman music literature class. Up to this point the most I knew about music other than rock or blues was that Beethoven was deaf, Mozart composed as a child, and Chopin wrote a really cool piano sonata in B-flat minor. So, we’re sitting in class learning about Berlioz, and all of the sudden it occurred to me: are there any composers still working today? So I risked looking silly and raised my hand to ask my professor if there were composers that were still working today. His response was, “Of course!” In discussing modern composers, the one medium that continuously came up in my literature class was that of film music. It occurred to me then that I knew a lot of modern orchestral music, even though I didn’t really know it. From the time when I was a little kid, I knew the name of John Williams. Some of my earliest memories involved seeing such movies as E.T., Raiders of the Lost Ark, and The Empire Strikes Back. My father was a musician, so I always noted the music credit in the opening credits. All of those films had the same composer, John Williams. Of course, I was only eight years old at the time, so in my mind I thought that John Williams wrote all the music for the movies. -

Neuer Nachrichtenbrief Der Gesellschaft Für Exilforschung E. V

Neuer Nachrichtenbrief der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung e. V. Nr. 56 ISSN 0946-1957 Dezember 2020 Inhalt In eigener Sache In eigener Sache 1 Jahrestagung 2020 1 Not macht erfinderisch, und die Corona- Protokoll Mitgliederversammlung 5 Not, die es unmöglich machte, sich wie AG Frauen im Exil 8 gewohnt zur Jahrestagung zu treffen, Call for Papers 2021 9 machte die Organisatorinnen so Exposé 2022 11 erfinderisch, dass sie eine eindrucksvolle Nachruf Ruth Klüger 13 Online-Tagung auf die Beine stellten, der Nachruf Lieselotte Maas 14 nichts fehlte – außer eben dem persönlichen Ausstellung Erika Mann 15 Austausch in den Pausen und beim Projekt Ilse Losa 17 Rahmenprogramm. So haben wir gemerkt, Neuerscheinungen 18 dass man virtuell wissenschaftliche Urban Exile 27 Ergebnisse präsentieren und diskutieren Ausstellung Max Halberstadt 29 kann, dass aber der private Dialog zwischen Suchanzeigen 30 den Teilnehmenden auch eine wichtige Leserbriefe 30 Funktion hat, die online schwer zu Impressum 30 realisieren ist. Wir hoffen also im nächsten Jahr wieder auf eine „Präsenz-Tagung“! Katja B. Zaich Aus der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung Fährten. Mensch-Tier-Verhältnisse in Reflexionen des Exils Virtuelle Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung e.V. in Zusammenarbeit mit der Österreichischen Exilbibliothek im Literaturhaus Wien und der Gesellschaft der Freunde der Österreichischen Exilbibliothek vom 22. bis 24. Oktober 2020 Die interdisziplinäre Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung e.V. fand 2020 unter den besonderen Umständen der Corona-Pandemie statt. Wenngleich die persönliche Begegnung fehlte, ist es den Veranstalterinnen gelungen, einen regen wissenschaftlichen Austausch im virtuellen Raum zu ermöglichen. Durch die Vielfalt medialer Präsentationsformen wurden die Möglichkeiten digitaler Wissenschaftskommunikation für alle Anwesenden erfahrbar. -

Volume 75, Number 01 (January 1957) Guy Mccoy

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1957 Volume 75, Number 01 (January 1957) Guy McCoy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation McCoy, Guy. "Volume 75, Number 01 (January 1957)." , (1957). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/79 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • ••• BEST "tell then certainInlvy yvou want •a Progressive Series Plan teacher. us a story ... " I ke a career of private P~ogressive .Series te~~le~a:a excellent music backgrounds ~~~n~h:eya~~~~;l~~v~tm~ the high standa~s ref~~redto (an Ada Richter musical story, of course I) be eligible for an Appointment as a teu: er 0 e Progressive, Series Plan' of Music Education. piano beginners ••. why not a musical story? Yes. YOJ.lrchild deserves the best, he deserves a (like all children) love the magic of storyland. Bright Progressive Series Plan teacher. Every year more piano teachers turn to musical stories eyes grow brighter-interest reaches a new high at I h.ild receives the BEST to enhance their regular piano lessons. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras.