An Examination of Jerry Goldsmith's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood

Katherine Kinney Cold Wars: Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood n 1982 Louis Gossett, Jr was awarded the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Gunnery Sergeant Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman, becoming theI first African American actor to win an Oscar since Sidney Poitier. In 1989, Denzel Washington became the second to win, again in a supporting role, for Glory. It is perhaps more than coincidental that both award winning roles were soldiers. At once assimilationist and militant, the black soldier apparently escapes the Hollywood history Donald Bogle has named, “Coons, Toms, Bucks, and Mammies” or the more recent litany of cops and criminals. From the liberal consensus of WWII, to the ideological ruptures of Vietnam, and the reconstruction of the image of the military in the Reagan-Bush era, the black soldier has assumed an increasingly prominent role, ironically maintaining Hollywood’s liberal credentials and its preeminence in producing a national mythos. This largely static evolution can be traced from landmark films of WWII and post-War liberal Hollywood: Bataan (1943) and Home of the Brave (1949), through the career of actor James Edwards in the 1950’s, and to the more politically contested Vietnam War films of the 1980’s. Since WWII, the black soldier has held a crucial, but little noted, position in the battles over Hollywood representations of African American men.1 The soldier’s role is conspicuous in the way it places African American men explicitly within a nationalist and a nationaliz- ing context: U.S. history and Hollywood’s narrative of assimilation, the combat film. -

Of Monsters and Mothers: Representations of Motherhood in ‘Alien’

Aditya Hans Prasad WGSS 07 Professor Douglas Moody April 2018. Of Monsters and Mothers: Representations of Motherhood in ‘Alien’ Released in 1979, director Ridley Scott’s film Alien is renowned as one of the few science fiction films that surpasses most horror films in its power to terrify an audience. The film centers on the crew of the spaceship ‘Nostromo’, and how the introduction of an unknown alien life form wreaks havoc on the ship. The eponymous Alien individually murders each member of the crew, aside from the primary antagonist Ripley, who manages to escape. Interestingly, the film uses subtle representations of motherhood in order to create a truly scary effect. These representations are incredibly interesting to study, as they tie in to various existing archetypes surrounding motherhood and the concept of the ‘monstrous feminine’. In her essay ‘Alien and the Monstrous Feminine’, Barbara Creed discusses the various notions that surround motherhood. First, she writes about the “ancient archaic figure who gives birth to all living things” (Creed 131). Essentially, she discusses the great mother figures of the mythologies of different cultures—Gaia, Nu Kwa, Mother Earth (Creed 131). These characters embody the concept that mothers are nurturing, loving, and caring. Traditionally, stories, films, and other forms of material reiterate and r mothers in this nature. However, there are many notable exceptions to this representation. For example, the primary antagonist in many Brothers Grimm stories are the evil step-mother, a character completely devoid of the maternal warmth and nurturing character of the traditional mother. In Hindu mythology, the goddess Kali is worshipped as the mother of the universe. -

Dominic Muldowney

Update April 2019 Dominic Muldowney The Anatomy Lesson (1993) Sinfonietta/Dominic Muldowney violin and piano Score 0-571-56341-4 (fp) on sale, parts for hire 8 minutes Commissioned by Tasmin Little with funds from the John S Cohen Concerto for Trumpet (1993) Foundation trumpet and orchestra with click-track tape FP: 12.10.1993, Pasydy Theatre, South Nicosia, Cyprus: Tasmin Little/ 20 minutes Piers Lane 2.2.2.2(II=cbsn) – 2000 – perc(2): 4 wdbl/2 susp.cym/2 mar – pno – Piano score and part 0-571-51469-3 (fp) on sale strings (Elec requirements): pre-recorded click-track tape/7 earpieces for The Brontes Suite (1998) conductor, tpt solo, pno, 2 cls and 2 perc Commissioned by the Premiere Ensemble and South Bank Centre and orchestra supported by the Arts Council of Great Britain 12 minutes FP: 14.6.1993, Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, UK: John Wallace/ 1(=picc).1.2(II=bcl).2(II=cbsn) – 2100 – perc(1): SD/BD+ped/3 tpl.bl/ Premiere Ensemble/Mark Wigglesworth wdbl/bongos/tgl/mcas/cabaca/susp.cym/glsp – pno – strings Score, parts and click-track tape for hire FP: 9.3.1998, St John’s Smith Square, London, UK: Orchestra of St John’s Smith Square/John Lubbock Score and parts for hire Concerto for Violin (1989) violin, large orchestra, tape, two conductors and click- The Brontes (1995) track tape Ballet for orchestra 26 minutes 120 minutes 3(II+III=picc).2.3.2(=cbsn) – 4431 – perc(4): 4 wdbl/4 tpl.bl/4 1121 – 2110 – perc(2): claves/tom-t/2 tamb/BD/glsp/vib/tgl/susp.cym/ sandblock/2 claves/4 conga/2 cabaca/2 BD/2 tom-t/2 tam-t/2 mar/2 SD/cabassa/tam-t/xylo/congas/bongos/tpl.bl/mcas/3 wdbl – keyboard susp.cym/2 splash cym/2 tgl/2 drum kit(=hi-hat/SD/BD+foot ped)/2 – harp – strings mcas or chocalho – 2 harp – strings FP: 6.3.1995, Grand Theatre, Leeds, UK: Northern Ballet Theatre (Elec requirements): pre-recorded 4-track tape, 6 radio earpieces to Score and parts for hire the 2 conductors and 4 perc. -

The Retriever, Issue 1, Volume 39

18 Features August 31, 2004 THE RETRIEVER Alien vs. Predator: as usual, humans screwed it up Courtesy of 20th Century Fox DOUGLAS MILLER After some groundbreaking discoveries on Retriever Weekly Editorial Staff the part of the humans, three Predators show up and it is revealed that the temple functions as prov- Many of the staple genre franchises that chil- ing ground for young Predator warriors. As the dren of the 1980’s grew up with like Nightmare on first alien warriors are born, chaos ensues – with Elm street or Halloween are now over twenty years Weyland’s team stuck right in the middle. Of old and are beginning to loose appeal, both with course, lots of people and monsters die. their original audience and the next generation of Observant fans will notice that Anderson’s filmgoers. One technique Hollywood has been story is very similar his own Resident Evil, but it exploiting recently to breath life into dying fran- works much better here. His premise is actually chises is to combine the keystone character from sort of interesting – especially ideas like Predator one’s with another’s – usually ending up with a involvement in our own development. Anderson “versus” film. Freddy vs. Jason was the first, and tries to allow his story to unfold and build in the now we have Alien vs. Predator, which certainly style of Alien, withholding the monsters almost will not be the last. Already, the studios have toyed altogether until the second half of the film. This around with making Superman vs. Batman, does not exactly work. -

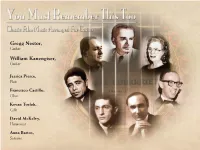

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Musical Intelligences and Human Instruments in Science Fiction and Film

SINGING MACHINES: MUSICAL INTELLIGENCES AND HUMAN INSTRUMENTS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FILM by Nicholas Christian Laudadio October 8, 2004 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The State University of New York at Buffalo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Copyright by Nicholas Christian Laudadio 2004 ii Sincerely felt and appropriately formatted thanks to: My committee members: Joseph Conte (director), James Bono, James Bunn (with tremendous help along the way from Charles Bernstein and Chip Delaney) My outside reader: Bernadette Wegenstein My parents And most certainly to Meghan Sweeney, without whom all goes poof, &c. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Setting the Mood Organ: An Introduction 1 CHAPTER ONE The Song of Last Words: Kubrick’s 2001 and the Acoustic Moment of Disconnection 13 CHAPTER TWO Just Like So But Isn’t: Listening AIs, Recursive Disconnection, and Richard Powers’s Galatea 2.2 56 CHAPTER THREE Instrumentes of Musyk: An Organological Approach to Lloyd Biggle Jr.’s “The Tunesmith” 93 CHAPTER FOUR What Dreams Sound Like: Forbidden Planet and a Material History of the Electronic Musical Instrument 135 WORKS CITED 179 iv ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1: Frank Poole Jogging in the Ship from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey 22 Figure 2: Frank and Dave Discuss HAL’s Fate from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey 41 Figure 3: HAL Disconnected from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey 47 Figure 4: “The Organist and His Wife” by Israel Van Meckenem 94 Figure 5: The Telharmonium from “120 Years of Electronic Musical Instruments” 145 Figure 6: Clara Rockmore 151 Figure 7: Raymond Scott and his Family from Gert-Jan Blom’s Manhattan Research, Inc. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

Musikliste Zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel Sortiert in Der Reihenfolge, in Der Sie in Der Doku Zu Hören Sind

Z Musikliste zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel sortiert in der Reihenfolge, in der sie in der Doku zu hören sind. Folge 1 MUSIK - Titel CD / Interpret Composer Trailer Terra X Trailer Terra X Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Dr. Ford Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Ramin Djawadi Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Eleven Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Race To Mark's Flat Bridget Jones's Baby / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Boggis, Bunce and Fantastic Mr. Fox / Alexandre Desplat Alexandre Desplat Bean Hibernation Pod 1625 Passengers / Thomas Newman Thomas Newman Jack It Up Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Letters Theodore Shapiro Reporters Swarm Confirmation / Harry Gregson Williams Harry Gregson Williams Persistence Burnt / Rob Simonsen Rob Simonsen Introducing Howard Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Inlet Theodore Shapiro The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Theodore Shapiro Letters Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Fell Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers Me Before You Me Before You / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Orchestral This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon The Skylab Plan Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Speight Lived Here The Knick (Season 2) / Cliff Martinez Cliff Martinez This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon 3 Minutes Of Moderat A New Beginning Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers 3 Minutes Of Moderat The Walk The Walk / Alan Silvestri Alan Silvestri Dr. -

We Have Liftoff! the Rocket City in Space SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 • 7:30 P.M

POPS FOUR We Have Liftoff! The Rocket City in Space SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 • 7:30 p.m. • MARK C. SMITH CONCERT HALL, VON BRAUN CENTER Huntsville Symphony Orchestra • C. DAVID RAGSDALE, Guest Conductor • GREGORY VAJDA, Music Director One of the nation’s major aerospace hubs, Huntsville—the “Rocket City”—has been heavily invested in the industry since Operation Paperclip brought more than 1,600 German scientists to the United States between 1945 and 1959. The Army Ballistic Missile Agency arrived at Redstone Arsenal in 1956, and Eisenhower opened NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in 1960 with Dr. Wernher von Braun as Director. The Redstone and Saturn rockets, the “Moon Buggy” (Lunar Roving Vehicle), Skylab, the Space Shuttle Program, and the Hubble Space Telescope are just a few of the many projects led or assisted by Huntsville. Tonight’s concert celebrates our community’s vital contributions to rocketry and space exploration, at the most opportune of celestial conjunctions: July 2019 marked the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon-landing mission, and 2020 brings the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, America’s leading aerospace museum and Alabama’s largest tourist attraction. S3, Inc. Pops Series Concert Sponsors: HOMECHOICE WINDOWS AND DOORS REGIONS BANK Guest Conductor Sponsor: LORETTA SPENCER 56 • HSO SEASON 65 • SPRING musical selections from 2001: A Space Odyssey Richard Strauss Fanfare from Thus Spake Zarathustra, op. 30 Johann Strauss, Jr. On the Beautiful Blue Danube, op. 314 Gustav Holst from The Planets, op. 32 Mars, the Bringer of War Venus, the Bringer of Peace Mercury, the Winged Messenger Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity INTERMISSION Mason Bates Mothership (2010, commissioned by the YouTube Symphony) John Williams Excerpts from Close Encounters of the Third Kind Alexander Courage Star Trek Through the Years Dennis McCarthy Jay Chattaway Jerry Goldsmith arr. -

Film Music Week 4 20Th Century Idioms - Jazz

Film Music Week 4 20th Century Idioms - Jazz alternative approaches to the romantic orchestra in 1950s (US & France) – with a special focus on jazz... 1950s It was not until the early 50’s that HW film scores solidly move into the 20th century (idiom). Alex North (influenced by : Bartok, Stravinsky) and Leonard Rosenman (influenced by: Schoenberg, and later, Ligeti) are important influences here. Also of note are Georges Antheil (The Plainsman, 1937) and David Raksin (Force of Evil, 1948). Prendergast suggests that in the 30’s & 40’s the films possessed somewhat operatic or unreal plots that didn’t lend themselves to dissonance or expressionistic ideas. As Hollywood moved towards more realistic portrayals, this music became more appropriate. Alex North, leader in a sparser style (as opposed to Korngold, Steiner, Newman) scored Death of a Salesman (image above)for Elia Kazan on Broadway – this led to North writing the Streetcar film score for Kazan. European influences Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). • Director Frederico Fellini &composer Nino Rota (many examples) • Director François Truffault & composerGeorges Delerue, • Composer Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the • Professionals, 1966, Composer- Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). (continued) Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background).