Underwater Music: Tuning Composition to the Sounds of Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

Of Monsters and Mothers: Representations of Motherhood in ‘Alien’

Aditya Hans Prasad WGSS 07 Professor Douglas Moody April 2018. Of Monsters and Mothers: Representations of Motherhood in ‘Alien’ Released in 1979, director Ridley Scott’s film Alien is renowned as one of the few science fiction films that surpasses most horror films in its power to terrify an audience. The film centers on the crew of the spaceship ‘Nostromo’, and how the introduction of an unknown alien life form wreaks havoc on the ship. The eponymous Alien individually murders each member of the crew, aside from the primary antagonist Ripley, who manages to escape. Interestingly, the film uses subtle representations of motherhood in order to create a truly scary effect. These representations are incredibly interesting to study, as they tie in to various existing archetypes surrounding motherhood and the concept of the ‘monstrous feminine’. In her essay ‘Alien and the Monstrous Feminine’, Barbara Creed discusses the various notions that surround motherhood. First, she writes about the “ancient archaic figure who gives birth to all living things” (Creed 131). Essentially, she discusses the great mother figures of the mythologies of different cultures—Gaia, Nu Kwa, Mother Earth (Creed 131). These characters embody the concept that mothers are nurturing, loving, and caring. Traditionally, stories, films, and other forms of material reiterate and r mothers in this nature. However, there are many notable exceptions to this representation. For example, the primary antagonist in many Brothers Grimm stories are the evil step-mother, a character completely devoid of the maternal warmth and nurturing character of the traditional mother. In Hindu mythology, the goddess Kali is worshipped as the mother of the universe. -

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

The Retriever, Issue 1, Volume 39

18 Features August 31, 2004 THE RETRIEVER Alien vs. Predator: as usual, humans screwed it up Courtesy of 20th Century Fox DOUGLAS MILLER After some groundbreaking discoveries on Retriever Weekly Editorial Staff the part of the humans, three Predators show up and it is revealed that the temple functions as prov- Many of the staple genre franchises that chil- ing ground for young Predator warriors. As the dren of the 1980’s grew up with like Nightmare on first alien warriors are born, chaos ensues – with Elm street or Halloween are now over twenty years Weyland’s team stuck right in the middle. Of old and are beginning to loose appeal, both with course, lots of people and monsters die. their original audience and the next generation of Observant fans will notice that Anderson’s filmgoers. One technique Hollywood has been story is very similar his own Resident Evil, but it exploiting recently to breath life into dying fran- works much better here. His premise is actually chises is to combine the keystone character from sort of interesting – especially ideas like Predator one’s with another’s – usually ending up with a involvement in our own development. Anderson “versus” film. Freddy vs. Jason was the first, and tries to allow his story to unfold and build in the now we have Alien vs. Predator, which certainly style of Alien, withholding the monsters almost will not be the last. Already, the studios have toyed altogether until the second half of the film. This around with making Superman vs. Batman, does not exactly work. -

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131 Instructor: Madison Heying Email: [email protected] Office Hours: By Appointment Course Description: This course is a survey of the history and literature of electronic music. In each class we will learn about a music-making technique, composer, aesthetic movement, and the associated repertoire. Tests and Quizzes: There will be one test for this course. Students will be tested on the required listening and materials covered in lectures. To be prepared students must spend time outside class listening to required listening, and should keep track of the content of the lectures to study. Assignments and Participation: A portion of each class will be spent learning the techniques of electronic and computer music-making. Your attendance and participation in this portion of the class is imperative, since you will not necessarily be tested on the material that you learn. However, participation in the assignments and workshops will help you on the test and will provide you with some of the skills and context for your final projects. Assignment 1: Listening Assignment (Due June 30th) Assignment 2: Field Recording (Due July 12th) Final Project: The final project is the most important aspect of this course. The following descriptions are intentionally open-ended so that you can pursue a project that is of interest to you; however, it is imperative that your project must be connected to the materials discussed in class. You must do a 10-20 minute in class presentation of your project. You must meet with me at least once to discuss your paper and submit a ½ page proposal for your project. -

French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed As a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G. Cale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Cale, John G., "French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2112. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2112 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72-17,750 CALE, John G., 1922- FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College;, Ph.D., 1971 Music I University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by John G. Cale B.M., Louisiana State University, 1943 M.A., University of Michigan, 1949 December, 1971 PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. -

Computer Music

THE OXFORD HANDBOOK OF COMPUTER MUSIC Edited by ROGER T. DEAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. First published as an Oxford University Press paperback ion Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Oxford handbook of computer music / edited by Roger T. Dean. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-979103-0 (alk. paper) i. Computer music—History and criticism. I. Dean, R. T. MI T 1.80.09 1009 i 1008046594 789.99 OXF tin Printed in the United Stares of America on acid-free paper CHAPTER 12 SENSOR-BASED MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AND INTERACTIVE MUSIC ATAU TANAKA MUSICIANS, composers, and instrument builders have been fascinated by the expres- sive potential of electrical and electronic technologies since the advent of electricity itself. -

Insufficient Concern: a Unified Conception of Criminal Culpability

Insufficient Concern: A Unified Conception of Criminal Culpability Larry Alexandert INTRODUCTION Most criminal law theorists and the criminal codes on which they comment posit four distinct forms of criminal culpability: purpose, knowl- edge, recklessness, and negligence. Negligence as a form of criminal cul- pability is somewhat controversial,' but the other three are not. What controversy there is concerns how the lines between them should be drawn3 and whether there should be additional forms of criminal culpabil- ity besides these four.' My purpose in this Essay is to make the case for fewer, not more, forms of criminal culpability. Indeed, I shall try to demonstrate that pur- pose and knowledge can be reduced to recklessness because, like reckless- ness, they exhibit the basic moral vice of insufficient concern for the interests of others. I shall also argue that additional forms of criminal cul- pability are either unnecessary, because they too can be subsumed within recklessness as insufficient concern, or undesirable, because they punish a character trait or disposition rather than an occurrent mental state. Copyright © 2000 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Incorporated (CLR) is a California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their publications. f Warren Distinguished Professor of Law, University of San Diego. I wish to thank all the participants at the Symposium on The Morality of Criminal Law and its honoree, Sandy Kadish, for their comments and criticisms, particularly Leo Katz and Stephen Morse, who gave me comments prior to the event, and Joshua Dressler, whose formal Response was generous, thoughtful, incisive, and prompt. -

Knowledge Organiser

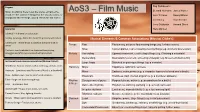

Key Composers Purpose Bernard Hermann James Horner Music in a film is there to set the scene, enhance the AoS3 – Film Music mood, tell the audience things that the visuals cannot, or John Williams Danny Elfman manipulate their feelings. Sound effects are not music! John Barry Alan Silvestri Jerry Goldsmith Howard Shore Key terms Hans Zimmer Leitmotif – A theme for a character Mickey-mousing – When the music fits precisely with action Musical Elements & Common Associations (Musical Cliche’s) Underscore – where music is played at the same time as action Tempo Fast Excitement, action or fast-moving things (eg. A chase scene) Slow Contemplation, rest or slowing-moving things (eg. A funeral procession) Fanfare – short melodies from brass sections playing arpeggios and often accompanied with percussion Melody Ascending Upward movement, or a feeling of hope (eg. Climbing a mountain) Descending Downward movement, or feeling of despair (eg. Movement down a hill) Instruments and common associations (Musical Clichés) Large leaps Distorted or grotesque things (eg. a monster) Woodwind - Natural sounds such as bird song, animals, rivers Harmony Major Happiness, optimism, success Bassoons – Sometimes used for comic effect (i.e. a drunkard) Minor Sadness, seriousness (e.g. a character learns of a loved one’s death) Brass - Soldiers, war, royalty, ceremonial occasions Dissonant Scariness, pain, mental anguish (e.g. a murderer appears) Tuba – Large and slow moving things Rhythm Strong sense of pulse Purposefulness, action (e.g. preparations for a battle) & Metre Harp – Tenderness, love Dance-like rhythms Playfulness, dancing, partying (e.g. a medieval feast) Glockenspiel – Magic, music boxes, fairy tales Irregular rhythms Excitement, unpredictability (e.g. -

PDF of This Issue

MIT’s The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Cloudy, 45°F (8°C) Tonight: Cloudy, 38°F (3°C) Newspaper Tomorrow: Rain, 38°F (3°C) Details, Page 2 Volume 124, Number 57 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Tuesday, November 30, 2004 Bug in MyMIT System Allowed Sharing of Users’ Information By Jeffrey Chang Redwine said. In those circum- “We then had to spend a few STAFF REPORTER stances, a user could see the informa- weeks trying to understand the MIT Admissions e-mailed about tion from someone else’s registration extent of possible access to informa- 9,500 registered users of the MyMIT or application. tion,” Redwine said. Of the total admissions Web site last week to con- MIT was alerted to this problem number of people who had used the firm that their applications were cor- by a student using the portal. “As portal, about 20 percent potentially rect after discovering and correcting a soon as we heard, we took the portal could have been affected. Out of that problem where users could potential- down,” Redwine said, causing the group, only a quarter, or about ly access other students’ applications. inaccessibility of the MyMIT site 2,400, were students who had MIT Admissions realized in late around Nov. 1 and the subsequent already submitted their applications. October that under some circum- extension of the Early Action appli- stances, a user of the site could find cation deadline. It took a couple Applicants alerted via e-mail himself or herself with the same ses- days, but the difficulty, a hardware “We have recently corrected a sion ID as someone else, Dean for configuration problem, was straight- Undergraduate Education Robert P. -

Music to My Ears: a Structural Approach to Teaching the Soundtrack

Music to My Ears: A Structural Approach to Teaching the Soundtrack Kathryn Kalinak Introduction and Rationale In one of the first film classes I ever took, the professor described the aim of the course as visual indoctrination: to loose the innocence of the untrained eye. Looking back on my own experi ence as a professor of film studies, I have come to realize how apt his characterization remains today. Beginning film students quickly learn the vocabulary to describe a film's image track. Mise-en-scene, camera position and movement, focal distance, and editing are common currency in the textbooks and courses which introduce film as an art form in colleges and universities across the country. Within the last decade there has been a noticeable effort to regard the soundtrack with the same attention: increased scholarship in the area, especially in terms of theory, and more and better chapters on the soundtrack in film textbooks. As a result, film students are growing more comfortable with the concepts and language necessary to describe the ways in which sound can be constructed. Yet how many film courses, introductory or otherwise, give equal time to the soundtrack? (c) 1991 Kathryn Kalinak 30 Indiana Theory Review Vol. 11 The case with film music is even more pronounced. Music is one of the most basic elements of the cinematic apparatus, but the vast majority of film students, undergraduate and graduate, will complete their degrees without ever formally studying it. Those students who do show an interest or aptitude often find their way to music departments where courses in film music are becoming more and more common. -

Alan Silvestri

ALAN SILVESTRI AWARDS/NOMINATIONS EMMY NOMINATION (2014) COSMOS: A SPACETIME ODYSSEY Outstanding Music Composition for a Series / Original Dramatic Score and Outstanding Original Main Title Music WORLD SOUNDTRACK NOMINATION (2008) “A Hero Comes Home” from BEOWULF Best Original Song Written for Film* INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC CRITICS BEOWULF ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2007) Best Original Score-Animated Feature GRAMMY AWARD (20 05) “Believe” from THE POLAR EXPRESS Best Song Written for a Motion Picture* ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2005) “Believe” from THE POLAR EXPRESS Best Original Song* GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2005) “Believe” from THE POLAR EXPRESS Best Original Song* BRO ADCAST FILM CRITICS CHOICE “Believe” from THE POLAR EXPRESS NOMINATION (2004) Best Song* GRAMMY AWARD (2001) End Credits from CAST AWAY Best Instrumental Composition ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1994) FORREST GUMP Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINA TION (1994) “Feather” from FORREST GUMP Best Instrumental Performance GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1994) FORREST GUMP Best Original Score CABLE ACE AWARD (1990) TALES FROM THE CRYPT: ALL THROUGH Best Original Score THE HOUSE GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1989) Suite from WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT? Best Instrumental Composition GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1988) WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT? Best Album of Original Score Written for a Motion Picture GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1985) BA CK TO THE FUTURE Best Instrumental Composition 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency (818) 260-8500 ALAN SILVESTRI GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1985) BACK TO THE FUTURE Best Album of Original Score Written for a Motion Picture *shared nomination/award MOTION PICTURES RUN ALL NIGHT Roy Lee / Michael Tadross / Brooklyn Weaver, prods. Warner Brothers Jaume Collet-Serra, dir. RED 2 Lorenzo di Bonaventura / Mark Vahradian, prods.