On Biomedicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mindful Body: a Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology

ARTICLES NANCYSCHEPER-HUGHES Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley MARGARETM. LOCK Department of Humanities and Social Studies in Medicine, McGill University The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology Conceptions of the body are central not only to substantive work in med- ical anthropology, but also to the philosophical underpinnings of the en- tire discipline of anthropology, where Western assumptions about the mind and body, the individual and socieo, affect both theoretical view- points and research paradigms. These same conceptions also injluence ways in which health care is planned and delivered in Western societies. In this article we advocate the deconstruction of received concepts about the body and begin this process by examining three perspectives from which the body may be viewed: (1) as a phenomenally experienced indi- vidual body-self; (2) as a social body, a natural symbol for thinking about relationships among nature, sociev, and culture; and (3)as a body politic, an artifact of social and political control. After discussing ways in which anthropologists, other social scientists, and people from various cultures have conceptualized the body, we propose the study of emotions as an area of inquiry that holds promise for providing a new approach to the subject. The body is the first and most natural tool of man-Marcel Maw(19791 19501) espite its title this article does not pretend to offer a comprehensive review of the anthropology of the body, which has its antecedents in physical, Dpsychological, and symbolic anthropology, as well as in ethnoscience, phenomenology, and semiotics.' Rather, it should be seen as an attempt to inte- grate aspects of anthropological discourse on the body into current work in med- ical anthropology. -

The Rights of Children in Biomedicine: Challenges Posed by Scientific Advances and Uncertainties

The Rights of Children in Biomedicine: Challenges posed by scientific advances and uncertainties Kavot Zillén, Jameson Garland, & Santa Slokenberga Table of Contents About the Authors ...................................................................................................................... v Executive summary .................................................................................................................... 1 Resumé ....................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 The aims of the report ...................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Scientific challenges in biomedicine, pediatric care, and law .......................................... 5 1.2.1 Identifying the vulnerabilities and diversity of children as a class ........................... 5 1.2.2 Conceptualizing risk in relation to scientific advances, uncertainties, and rights ..... 6 1.2.3 Locating uncertainty and risk in biomedicine ........................................................... 7 1.3 The parameters and methodology of the report ............................................................... 8 1.4 The structure and disposition of the report ..................................................................... 10 2. Child development and its relation -

Health Science: Biomedicine Public Service Endorsement

INNOVATE • COLLABORATE • EDUCATE • INNOVATE • COLLABORATE • EDUCATE Health Science: Biomedicine Public Service Endorsement Career Pathways • Biochemist • Biomedical Engineer • Biophysicist • Physician, Surgeon Certifications / Certificate Options • CPR • OSHA Program Highlights Biomedical engineering represents new areas of medical research and • Pathogen Analysis product development; biomedical engineers’ work helps pave the way • Human Anatomy & Physiology for new ways to help treat injuries and diseases. As medicine is a field • DNA / Genomics with vast numbers of specific disciplines, there are many different sub- • Laboratory Procedures fields in which biomedical engineers work. Some work to improve and • Dissection develop new machinery, such as robotic surgery equipment; others • Grow and Culture Bacteria endeavor to create better, more reliable replacement limbs (or parts • Real World Research which help existing limbs function better, such as joint replacements). • Learn to Treat Patients New and more comfortable patient beds, monitoring equipment, and electronics are also products that often begin as concepts from the CTSO(s) biomedical engineer’s or involve some level of input from them. • HOSA - Future Health Professionals KISD Biomedical Program: Program Fees / Requirements Biomedicine classes in KISD aim to prepare students to enter the • HOSA membership (Optional) health care field by giving them a foundation in real world problems, medical treatments, and a better understanding of the human body. Program Location Students will investigate causes and treatments of diseases that R Course(s) available at CHS affect the entire world as well as ones found in our own community. R Course(s) available at FRHS Students learn advanced techniques used in hospitals and research R Course(s) available at KHS labs and will become familiar with protocols used by doctors and R Course(s) available at TCHS researchers today. -

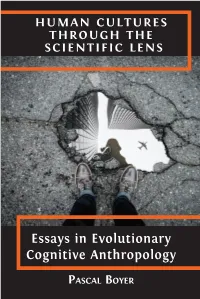

Essays in Evolutionary Cognitive Anthropology

P HUMAN CULTURES THROUGH ASCAL HUMAN CULTURES THE SCIENTIFIC LENS B THROUGH THE Essays in Evolutionary OYER SCIENTIFIC LENS Cognitive Anthropology PASCAL BOYER This volume brings together a collection of seven articles previously published by the author, with a new introduction reframing the articles in the context of past and present the Scientific Lens through Human Cultures questions in anthropology, psychology and human evolution. It promotes the perspective of ‘integrated’ social science, in which social science questions are addressed in a deliberately eclectic manner, combining results and models from evolutionary biology, experimental psychology, economics, anthropology and history. It thus constitutes a welcome contribution to a gradually emerging approach to social science based on E. O. Wilson’s concept of ‘consilience’. Human Cultures through the Scientific Lensspans a wide range of topics, from an examination of ritual behaviour, integrating neuro-science, ethology and anthropology to explain why humans engage in ritual actions (both cultural and individual), to the motivation of conflicts between groups. As such, the collection gives readers a comprehensive and accessible introduction to the applications of an evolutionary paradigm in the social sciences. This volume will be a useful resource for scholars and students in the social sciences (particularly psychology, anthropology, evolutionary biology and the political sciences), as well as a general readership interested in the social sciences. This is the author-approved -

Biomedicine, Pharmacy and Health Care SECTORAL SERVICES of MATHEMATICAL RESEARCH Spanish Network for Mathematics & Industry for COMPANIES C/ Lope Gómez De Marzoa, S/N

Biomedicine, pharmacy and health care SECTORAL SERVICES OF MATHEMATICAL RESEARCH Spanish Network for Mathematics & Industry FOR COMPANIES C/ Lope Gómez de Marzoa, s/n. Campus Vida | CP 15782 Santiago de Compostela (A Coruña) Tel. 881 813 373 | 881 813 223 [email protected] | www.math-in.net math- in Biomedicine, Pharmacy and Health Care Specialized services Mathematics is an effective tool with proven ability to Biomedicine, Pharmacy and Health industries bring meet the demands and needs of businesses. In Spain, together the supply of 29 research groups of the i-MATH Biomedicine and Pharmacy many innovative solutions emerged from the experience project, of which up to 20 have proven experience from gained by research groups in this field through successful having effectively carried out consulting activities, training • Analysis and design of experiments. • Studies of efficacy and safety of treatments. partnerships with industry over the years. All those courses and other collaborations. The details of these • Characterization/grading of pharmaceutical and medical waste. encouraging cases support its potential in offering an groups can be found in the 'Sectors' section of the • Modelling of mortality tables. increasingly sophisticated and complete service to the platform www.math-in.net. • Numerical simulation of fractures, dental implants and orthodontic brackets. industry. • Biomechanics. Bones formation. The mathematical technology services provided in this • Bioinformatics. • Mathematical Biology. Synthetic Biology. The Spanish Network for Mathematics & Industry sector can be broken down into two blocks (on the one • Computational design of proteins. (math-in) is a stable platform that continues the work hand, Biomedicine and Pharmacy and, on the other • Metabolism. -

ANT476H1F-Syllabus.Pdf

Department of Anthropology University of Toronto ANT476H1F Body, Self and Sociality Fall 2014 Professor Janice Boddy AP 124 Office: AP 232 M 2:00-5:00 pm Office Hours: M 12-1:30, alternate Ts 1:30-3:30 Email: [email protected] Description We frequently take our bodies for granted as ‘natural’ and self-evident. But are they? The human body is at once a given of social and cultural life and a continuously created and contested entity. In this advanced undergraduate seminar we shake up our received understandings and examine ‘the body’ as a historically and culturally contingent category, the material site and means of practice, and a foundation point for identity and self-fashioning. We consider the relevance of cultural meanings to biomedical practices and imaginings of kinship, the centrality of the body to consumer techno-society, and the body’s role as a locus of experience, political inscription, and struggle. Readings examine and challenge the ostensible distinctions between ‘body’ and ‘mind’, and apparent limits of the body as a bounded, singular entity. Students will be exposed to several anthropological approaches to the human body as a social and cultural construct, and to topics of contemporary interest such as body modification and organ transplantation as well as classical ethnographic themes. Format Lectures, films, student presentations and group discussions grounded in weekly readings about bodies in specific social, cultural and historical contexts. Objectives In addition to having improved their written and oral expression and critical thinking skills, at the end of this course students can expect to: • Be knowledgeable about anthropological approaches to the body and embodiment and be able to evaluate their uses and pitfalls, • Have developed a knowing and respectful appreciation of people’s practices and ways of inhabiting their bodies, • Be able to critically assess practices, modes of control, and concepts of the body in light of current political, economic, social and technological conditions. -

Biomedicine and Health Innovation

Biomedicine and Health Innovation SYNTHESIS REPORT • Industrial Biotechnology • Green Growth • Bio-based Products • Measuring Performance OECD Innovation Strategy June 2010 Biomedicine and Health Innovation Synthesis Report November 2010 2 BIOMEDICINE AND HEALTH INNOVATION: SYNTHESIS REPORT Table of contents BIOMEDICINE AND HEALTH INNOVATION: SYNTHESIS REPORT ........................ 3 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 II. The changing nature of health innovation ............................................................. 4 III. Lessons and policy recommendations ................................................................... 7 IV. New policy challenges from advances in biomedicine ...................................... 14 Annex. Summary of OECD reports on biomedicine and health innovation ........ 19 OECD 2010 BIOMEDICINE AND HEALTH INNOVATION: SYNTHESIS REPORT 3 BIOMEDICINE AND HEALTH INNOVATION SYNTHESIS REPORT I. Introduction Over the past few years, the OECD has done important work in a number of areas related to innovation in biomedicine, including on: genetics and genomics, intellectual property rights and collaborative mechanisms and knowledge markets, health research infrastructures, translational research, regulatory policies that affect the approval and uptake of new technologies, and new business models for bringing health products to market, etc. This synthesis report presents the main lessons and policy messages that emerge -

Reflections on Humanizing Biomedicine

07_51.3marcum 392–405:02_51.3schwartz 320– 6/25/08 1:34 PM Page 392 Reflections on Humanizing Biomedicine James A. Marcum ABSTRACT Although biomedicine is responsible for the “miracles” of modern medicine, paradoxically it has also led to a quality-of-care crisis in which many patients feel disenfranchised from the health-care industry. To address this crisis, several medical commentators make an appeal for humanizing biomedicine, which has led to shifts in the philosophical boundaries of medical knowledge and practice. In this paper, the metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical boundaries of biomedicine and its human - ized versions are investigated and compared to one another. Biomedicine is founded on a metaphysical position of mechanistic monism, an epistemology of objective knowing, and an ethic of emotionally detached concern. In humanizing modern medicine, these boundaries are often shifted to a metaphysical position of dualism/holism, an episte - mology of subject knowing, and an ethic of empathic care. In a concluding section, the question is discussed whether these shifts in the philosophical boundaries are adequate to resolve the quality-of-care crisis. NAMOVING STORY OF a consultation for a second opinion over a diagnosis of I amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Mary O’Flaherty Horn (1999), the patient (and a practicing internist), relates the inhumanity and degradation with which she was treated by health-care providers. For example, during a procedure for test - ing the motor nerves “Dr. L”—the physician conducting the test—addressed his comments to attending residents instead of to her. “I might not have been pres - Department of Philosophy, Baylor University, One Bear Place #97273, Waco, TX 76798. -

Emotions in the Field: the Psychology and Anthropology of Fieldwork

Emotions in the Field Emotions in the Field The Psychology and Anthropology of Fieldwork Experience Edited by James Davies and Dimitrina Spencer Stanford University Press Stanford, California Stanford University Press Stanford, California ©2010 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Emotions in the field : the psychology and anthropology of fieldwork experience / edited by James Davies and Dimitrina Spencer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8047-6939-6 (cloth : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-0-8047-6940-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Ethnology--Fieldwork--Psychological aspects. 2. Emotions--Anthropological aspects. I. Davies, James (James Peter) II. Spencer, Dimitrina. GN346.E46 2010 305.8'00723--dc22 2009046034 Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 10/14 Minion Contents Acknowledgments vii Contributors ix Introduction: Emotions in the Field 1 James Davies Part I Psychology of Field Experience 1 From Anxiety to Method in Anthropological Fieldwork: An Appraisal of George Devereux’s Enduring Ideas 35 Michael Jackson 2 “At the Heart of the Discipline”: Critical Reflections on Fieldwork 55 Vincent -

Desire, Discord, and Death : Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Myth / by Neal Walls

DESIRE, DISCORD AND DEATH APPROACHES TO ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN MYTH ASOR Books Volume 8 Victor Matthews, editor Billie Jean Collins ASOR Director of Publications DESIRE, DISCORD AND DEATH APPROACHES TO ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN MYTH by Neal Walls American Schools of Oriental Research • Boston, MA DESIRE, DISCORD AND DEATH APPROACHES TO ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN MYTH Copyright © 2001 American Schools of Oriental Research Cover art: Cylinder seal from Susa inscribed with the name of worshiper of Nergal. Photo courtesy of the Louvre Museum. Cover design by Monica McLeod. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Walls, Neal H., 1962- Desire, discord, and death : approaches to ancient Near Eastern myth / by Neal Walls. p. cm. -- (ASOR books ; v. 8) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0-89757-056-1 -- ISBN 0-89757-055-3 (pbk.) 1. Mythology--Middle East. 2. Middle East--Literatures--History and crticism. 3. Death in literature. 4. Desire in literature. I. Title. II. Series. BL1060 .W34 2001 291.1'3'09394--dc21 2001003236 Contents ABBREVIATIONS vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS viii INTRODUCTION Hidden Riches in Secret Places 1 METHODS AND APPROACHES 3 CHAPTER ONE The Allure of Gilgamesh: The Construction of Desire in the Gilgamesh Epic INTRODUCTION 9 The Construction of Desire: Queering Gilgamesh 11 THE EROTIC GILGAMESH 17 The Prostitute and the Primal Man: Inciting Desire 18 The Gaze of Ishtar: Denying Desire 34 Heroic Love: Requiting Desire 50 The Death of Desire 68 CONCLUSION 76 CHAPTER TWO On the Couch with Horus and Seth: A Freudian -

Erica Caple James

Erica Caple James MIT Anthropology Program 77 Massachusetts Avenue Room E53-335G Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 (617) 253-7321 [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard University, Ph.D. in Social Anthropology 2003 Harvard University, A.M. in Social Anthropology 1998 Harvard Divinity School, Masters of Theological Studies (M.T.S.) 1995 Princeton University, A.B. in Anthropology 1992 DISSERTATION “The Violence of Misery: ‘Insecurity’ in Haiti in the ‘Democratic’ Era” Advisor: Dr. Arthur Kleinman FELLOWSHIPS AND HONORS Abdul Latif Jameel World Water and Food Security Lab Grant 2015-2017 Todman Family Fund, for launch of Global Health and Medical Humanities Initiative 2014 Alumni Class Funds 2014 Tenure, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2013 Gordon K. and Sybille Lewis (Book) Award, Caribbean Studies Association 2013 School for Advanced Research on the Human Experience, Advanced Seminar 2013 James A. and Ruth Levitan Prize in the Humanities, MIT 2012 Gregory Bateson Book Prize, Society for Cultural Anthropology, Honorable Mention 2011 MIT Old Dominion Fellowship 2011 Class of 1947 Career Development Professorship 2010 Rita E. Hauser Fellow, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study 2010-2011 MIT School of the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences Research Fund 2009 NIH National Loan Repayment Program Funding for Health Disparities Research 2007-2009 Career Enhancement Fellowship, Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation, 2007 Honorable Mention Mellon Foundation Support for the Study of Science, Technology, and Medicine 2006 School of the Humanities, -

DEADLY DISPUTES MARGARET LOCK LAWRENCE COHEN STEPHEN JAMISON CHARLES LESLIE GUY MICCO Deadly Disputes

DEADLY DISPUTES ALEXANDER CAPRON MARGARET LOCK LAWRENCE COHEN STEPHEN JAMISON CHARLES LESLIE GUY MICCO D O R E E N B. T O W N S E N D C E N T E R O C C A S I O N A L P A P E R S • 4 P A P L A S I O N A D O R E N B. T W S C Deadly Disputes Understanding Death in Europe, Japan, and North America THE DOREEN B. TOWNSEND CENER FOR THE HUMANITIES was established at the University of California at Berkeley in 1987 in order to promote interdisciplinary studies in the humanities. Endowed by Doreen B. Townsend, the Center awards fellowships to advanced graduate students and untenured faculty on the Berkeley campus, and supports interdisciplinary working groups, discussion groups, and team- taught graduate seminars. It also sponsors symposia and conferences which strengthen research and teaching in the humanities and related social science fields. The Center is directed by Thomas W. Laqueur, Professor of History. Christina M. Gillis has been Associate Director of the Townsend Center since 1988. DEADLY DISPUTES contains the proceedings of two symposia held in April of 1995 on the UC Berkeley Campus. On April 18, Professor Margaret Lock presented “Deadly Disputes: Biotechnology and Reconceptualizing the Body in Death in Japan and North America,” and on April 20, Professor Alexander Capron presented “Legalizing Physician-Assisted Death: A Skeptic’s View.” Both talks were part of the Townsend Center’s PROJECT ON DEATH AND DYING IN AMERICA, and were generously supported by the Academic Geriatric Resource Program.