Three Approaches to the Study of Health, Disease and Illness; the Strengths and Weaknesses of Each, with Special Reference to Refugee Populations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mindful Body: a Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology

ARTICLES NANCYSCHEPER-HUGHES Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley MARGARETM. LOCK Department of Humanities and Social Studies in Medicine, McGill University The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology Conceptions of the body are central not only to substantive work in med- ical anthropology, but also to the philosophical underpinnings of the en- tire discipline of anthropology, where Western assumptions about the mind and body, the individual and socieo, affect both theoretical view- points and research paradigms. These same conceptions also injluence ways in which health care is planned and delivered in Western societies. In this article we advocate the deconstruction of received concepts about the body and begin this process by examining three perspectives from which the body may be viewed: (1) as a phenomenally experienced indi- vidual body-self; (2) as a social body, a natural symbol for thinking about relationships among nature, sociev, and culture; and (3)as a body politic, an artifact of social and political control. After discussing ways in which anthropologists, other social scientists, and people from various cultures have conceptualized the body, we propose the study of emotions as an area of inquiry that holds promise for providing a new approach to the subject. The body is the first and most natural tool of man-Marcel Maw(19791 19501) espite its title this article does not pretend to offer a comprehensive review of the anthropology of the body, which has its antecedents in physical, Dpsychological, and symbolic anthropology, as well as in ethnoscience, phenomenology, and semiotics.' Rather, it should be seen as an attempt to inte- grate aspects of anthropological discourse on the body into current work in med- ical anthropology. -

'Medicine in Context'

FOUND IN TRANSLATION ‘Medicine in context’ An epistemological trajectory Hansjörg Dilger and Bernhard Hadolt Keywords theory, epistemology, context, globalization, transnationalism What is the role of medical anthropology in a globalized world that is becoming increasingly complex and interconnected? Where does the defining domain of our subdiscipline begin and end with regard to our ‘classical’ objects of study such as ‘medicine’, ‘health system(s)’, and ‘the body’, and how is it possible to decide what constitutes the anthropologically relevant ‘context’ of these (empirically defined) research fields? How can we open the horizons of the subdisciplines of social and cultural anthropology to medical anthropology, and to what extent do the demarcations between medical anthropology and other areas of the discipline that deal with politics, economics, law, science, religion, and urban environments even make sense? Where do the inter- and transdisciplinary junctions emerge that can provide for general reflections about the themes, challenges, and positions of medical anthropology in an interconnected world? These were the questions occupying our minds as we prepared for the conference ‘Medicine in Context: Illness and Health in an Interconnected World’, organized in 2007 by the Work Group Medical Anthropology within the German Anthropological Association on the occasion of its tenth anniversary. The following text forms the introduction to the anthology of the same name (Dilger and Hadolt 2010), which was published under our oversight as the Medicine Anthropology Theory 2, no. 3: 128–153; https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.2.3.333 © Hansjörg Dilger and Bernhard Hadolt. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5fv121wm Author Stroud, Martha Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia by Martha Stroud A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Chair Professor Laura Nader Professor Sharon Kaufman Professor Jeffrey A. Hadler Spring 2015 “Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia” © 2015 Martha Stroud 1 Abstract Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia by Martha Stroud Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Chair In Indonesia, during six months in 1965-1966, between half a million and a million people were killed during a purge of suspected Communist Party members after a purported failed coup d’état blamed on the Communist Party. Hundreds of thousands of Indonesians were imprisoned without trial, many for more than a decade. The regime that orchestrated the mass killings and detentions remained in power for over 30 years, suppressing public discussion of these events. It was not until 1998 that Indonesians were finally “free” to discuss this tragic chapter of Indonesian history. In this dissertation, I investigate how Indonesians perceive and describe the relationship between the past and the present when it comes to the events of 1965-1966 and their aftermath. -

Culture, Health and Illness (Introduction to Medical Anthropology)

Department of Anthropology, University of British Columbia Anthropology 227.001 Winter 2007 Culture, Health and Illness (Introduction to Medical Anthropology) Instructor Teaching Assistant Dr. Vinay R. Kamat Stephen Robbins Class: Mon, Wed, Fri 10:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. Office: ANSO 0305 Lasserre, 6333 Memorial Road, Room 104 Office hours: Mon, Wed, 11:00-12:00 Office: ANSO 2319; Office phone 604-822-4802 Email: [email protected] Office hours: Mon, Wed, 11:30 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Email: [email protected] Course Description This is an introductory course in medical anthropology which includes the study of health, illness and healing from a cross-cultural perspective. The course examines aspects of health and illness from a biocultural perspective. In reading ethnographic materials from Western and non-Western settings, we will explore how medical anthropologists creatively use different theoretical and methodological approaches to understand and highlight how health, illness and healing practices are culturally constructed and mediated. The case studies and other required readings will help us learn to appreciate the contribution of medical anthropology to the study of international public health problems including specific life-threatening diseases such as HIV/ AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. Topics covered by this course include cultural interpretations of sickness and healing, medical systems as social systems, medical pluralism, belief and ethnomedical systems, medical decision making, social relations of therapy management, cultural construction of efficacy and “side-effects,” pharmaceuticalization of health, explanatory models, cultural competence, narrative representation of illness, the body and debate surrounding female genital mutilation/ cutting, the political economy of HIV/AIDS in Africa, structural violence and social suffering, the New Genetics and social stigma. -

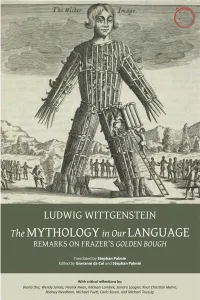

The Mythology in Our Language

THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough Translated by Stephan Palmié Edited by Giovanni da Col and Stephan Palmié With critical reflections by Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Hau Books Chicago © 2018 Hau Books and Ludwig Wittgenstein, Stephan Palmié, Giovanni da Col, Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Cover: “A wicker man, filled with human sacrifices (071937)” © The British Library Board. C.83.k.2, opposite 105. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Editorial office: Michelle Beckett, Justin Dyer, Sheehan Moore, Faun Rice, and Ian Tuttle Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-1-912808-40-3 LCCN: 2018962822 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is printed, marketed, and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Preface xi chapter 1 Translation is Not Explanation: Remarks on the Intellectual History and Context of Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer 1 Stephan Palmié chapter 2 Remarks on Frazer’s The Golden Bough 29 Ludwig Wittgenstein, translated by Stephan Palmié chapter 3 On Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough 75 Carlo Severi chapter 4 Wittgenstein’s -

Erica Caple James

Erica Caple James MIT Anthropology Program 77 Massachusetts Avenue Room E53-335G Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 (617) 253-7321 [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard University, Ph.D. in Social Anthropology 2003 Harvard University, A.M. in Social Anthropology 1998 Harvard Divinity School, Masters of Theological Studies (M.T.S.) 1995 Princeton University, A.B. in Anthropology 1992 DISSERTATION “The Violence of Misery: ‘Insecurity’ in Haiti in the ‘Democratic’ Era” Advisor: Dr. Arthur Kleinman FELLOWSHIPS AND HONORS Abdul Latif Jameel World Water and Food Security Lab Grant 2015-2017 Todman Family Fund, for launch of Global Health and Medical Humanities Initiative 2014 Alumni Class Funds 2014 Tenure, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2013 Gordon K. and Sybille Lewis (Book) Award, Caribbean Studies Association 2013 School for Advanced Research on the Human Experience, Advanced Seminar 2013 James A. and Ruth Levitan Prize in the Humanities, MIT 2012 Gregory Bateson Book Prize, Society for Cultural Anthropology, Honorable Mention 2011 MIT Old Dominion Fellowship 2011 Class of 1947 Career Development Professorship 2010 Rita E. Hauser Fellow, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study 2010-2011 MIT School of the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences Research Fund 2009 NIH National Loan Repayment Program Funding for Health Disparities Research 2007-2009 Career Enhancement Fellowship, Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation, 2007 Honorable Mention Mellon Foundation Support for the Study of Science, Technology, and Medicine 2006 School of the Humanities, -

INTRODUCTION a Concept Note

INTRODUCTION A Concept Note Clara Han and Veena Das Dōgen, a thirteenth-century Buddhist scholar from Japan, provocatively reversed the commonsense notion of life and death, which takes birth as the inception of a linear stretch of time over which a particular life is lived and death as the moment of cessation of that time. Instead, he thought that within Buddhist practice and hence within each moment, life and death can be seen as working together. What if we took such ways of conceptualizing the relation between life and death as present not only in exotic practices but also in concepts generated from the experiences of everyday life and its perils? Then we could become attentive to the multiple forms in which human societies generate understanding of life that comes from their varied experiences of how living and dying have been transformed in our contemporary conditions. This book is conceived as a response to the idea that our concepts are honed from the everyday experiences to which the people we study struggle to give expression, and to the idea that we ourselves become apprentices to death as we survey the altered landscape on which life and death become conjoined in our contemporary world. Our intention in this introductory chapter is not to summarize the chapters that follow: the section introductions show how the particular chapters in each section take forward the ways in which life and death are folded together in the lives of individuals and communities. Here we want to reflect on how anthropo- logical conceptions of life have absorbed the discussion of these issues from philosophy and from the history of medicine even as the anthropological attention to the concrete- ness of lives and deaths has put pressure on the abstract formulations of these other disciplines. -

Current Anthropology October 2015 Volume 56 Supplement 11 Pages S1–S180

Forthcoming Current Anthropology Wenner-Gren Symposium Current Anthropology Supplementary Issues (in order of appearance) VOLUME 56 SUPPLEMENT 11 OCTOBER 2015 The Life and Death of the Secret. Lenore Manderson, Mark Davis, and Current Chip Colwell, eds. Reintegrating Anthropology: From Inside Out. Agustín Fuentes and Polly Wiessner, eds. Anthropology Previously Published Supplementary Issues Working Memory: Beyond Language and Symbolism. Thomas Wynn and Frederick L. Coolidge, eds. THE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas. Setha M. Low and October 2015 Sally Engle Merry, eds. POLITICS OF THE URBAN POOR: AESTHETICS, Corporate Lives: New Perspectives on the Social Life of the Corporate Form. Damani Partridge, Marina Welker, and Rebecca Hardin, eds. ETHICS, VOLATILITY, PRECARITY The Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas. T. Douglas Price and GUEST EDITORS: VEENA DAS AND SHALINI RANDERIA Ofer Bar-Yosef, eds. The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, Politics of the Urban Poor: Aesthetics, Ethics, Volatility, Precarity National Styles, and International Networks. Susan Lindee and 56 Volume The Urban Poor and Their Ambivalent Exceptionalities: Notes from Jakarta Ricardo Ventura Santos, eds. The Politics of Not Studying the Poorest of the Poor in Urban South Africa Human Biology and the Origins of Homo. Susan Antón and Leslie C. Plebeians of the Arab Spring Aiello, eds. Political Leadership and the Urban Poor: Local Histories Potentiality and Humanness: Revisiting the Anthropological Object in The Need for Patience: The Politics of Housing Emergency in Buenos Aires Contemporary Biomedicine. Klaus Hoeyer and Karen-Sue Taussig, eds. The Politics of the Urban Poor in Postwar Colombo Supplement 11 Alternative Pathways to Complexity: Evolutionary Trajectories in the Middle Sectarianism and the Ambiguities of Welfare in Lebanon Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age. -

Gender and Sexuality

PERSPECTIVES: AN OPEN INTRODUCTION TO CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY SECOND EDITION Nina Brown, Thomas McIlwraith, Laura Tubelle de González 2020 American Anthropological Association 2300 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1301 Arlington, VA 22201 ISBN Print: 978-1-931303-67-5 ISBN Digital: 978-1-931303-66-8 http://perspectives.americananthro.org/ This book is a project of the Society for Anthropology in Community Colleges (SACC) http://sacc.americananthro.org/ and our parent organization, the American Anthropological Association (AAA). Please refer to the website for a complete table of contents and more information about the book. Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd Edition by Nina Brown, Thomas McIlwraith, Laura Tubelle de González is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Under this CC BY-NC 4.0 copyright license you are free to: Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material Under the following terms: Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. 1010 GENDER AND SEXUALITY Carol C. Mukhopadhyay, San Jose State University [email protected] http://www.sjsu.edu/people/carol.mukhopadhyay Tami Blumenfield, Yunnan University [email protected] with Susan Harper, Texas Woman’s University, [email protected], and Abby Gondek, [email protected] Learning Objectives • Identify ways in which culture shapes sex/gender and sexuality. -

Humanitarian Encounters in Post-Conflict Aceh, Indonesia The

Humanitarian Encounters in Post-Conflict Aceh, Indonesia The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation No citation. Accessed February 19, 2015 11:44:27 AM EST Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10433473 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA (Article begins on next page) Page intentionally left blank Humanitarian Encounters in Post-Conflict Aceh, Indonesia A dissertation presented by Jesse Hession Grayman to The Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Social Anthropology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 6 December 2012 © 2013-Jesse Hession Grayman Co-Advisor: Professor Byron J. Good Author: Jesse Hession Grayman Co-Advisor: Professor Mary M. Steedly ABSTRACT Humanitarian Encounters in Post-Conflict Aceh, Indonesia In “Humanitarian Encounters in Post-Conflict Aceh, Indonesia,” I examine the humanitarian involvement in Aceh, Indonesia following two momentous events in Aceh’s history: the earthquake and tsunami on 26 December 2004 and the signing of the Helsinki Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) that brought a tentative, peaceful settlement to the Free Aceh Movement’s (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, GAM) separatist insurgency against Indonesia on 15 August 2005. My research focuses on the international humanitarian engagement with Aceh’s peace process but frequently acknowledges the much larger and simultaneous tsunami recovery efforts along Aceh’s coasts that preceded and often overshadowed conflict recovery. -

Citizens and Anthropologists 59 CITIZENS AND

Citizens and Anthropologists 59 CITIZENS AND ANTHROPOLOGISTS Myriam Jimeno Introduction In this paper I propose to outline some of the debates and positions that have shaped anthropology in Colombia since it was established as a disciplinary and professional field in the mid 1940s. Although archeology, linguistics or biological anthropology might also be interesting perspectives from which to approach this subject, my intention here is to focus on socio-cultural anthropology. I will argue that the evolution of anthropology can be understood in terms of the tension between the global orientations of the discipline (concerning dominant narratives and practices, theories, field work, relations between subjects of study) and the way they are put into practice within the Colombian context. In countries such as Colombia, anthropological practice is permanently faced with the uneasy choice between adopting dominant anthropological concepts and orientations, or modifying them, adapting them, rejecting them and proposing alternatives. This need to adapt the practice stems from the specific social condition of anthropologists in these countries; that is, our dual position as both researchers and fellow citizens of our subjects of study, as a result of which we are continually torn between our duty as scientists and our role as citizens. From this perspective, there is a danger of falling into a nationalistic interpretation of the history of anthropology in Colombia. As Claudio Lomnitz (1999) ironically comments, such is the case of Mexican anthropology, -

Curriculum Vitae 2016

Curriculum Vitae 2016 Name MARY-JO DELVECCHIO GOOD Office Address Department of Global Health & Social Medicine Harvard Medical School 641 Huntington Ave. Boston, MA 02115 Ph. 617-432-2557, 617-432-0715 Email: [email protected] Education 1977 Ph.D. Harvard University, Department of Sociology and Center for Middle Eastern Studies 1969 M.A. Harvard University, Center for Middle Eastern Studies 1964 B.S. Simmons College, Government Academic Appointments 1983- Professor of Global Health and Social Medicine, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School (1996 appointed Professor) 1983- Professor (1996 HMS) Teaching in the Department of Sociology, FAS 2005- Faculty Associate, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs 2005- Faculty Council, Asia Center 1984- Faculty Associate, Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard University Fellowships and Awards 2015-2018 Co-PI, Center for Global Health Delivery–Dubai, Harvard Medical School, “Building a Program of Comprehensive Mental Health: Implementation and Evaluation of a Program of Integrated Mental Health Care in the Primary Health Care Centers of Yogyakarta” 2014-2016 Co-PI, Australian Research Council Grant (PI Hans Pols U Sydney): “Psychiatry in Indonesia: Historical and Contemporary” 2012 Silver Magnolia Award in recognition of outstanding contributions by foreigners to Shanghai’s economic, social and cultural development. Awarded by the Shanghai Municipal People’s Government at an award ceremony held in Shanghai, China, September 2012. 2000-16 Co-PI,