Download (4MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meteoswiss Good to Know Postdoc on Climate Change and Heat Stress

Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss MeteoSwiss Good to know The Swiss Federal Office for Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss is the Swiss National Weather Service. We record, monitor and forecast weather and climate in Switzerland and thus make a sus- tainable contribution to the well-being of the community and to the benefit of industry, science and the environment. The Climate Department carries out statistical analyses of observed and modelled cli- mate data and is responsible for providing the results for users and customers. Within the team Cli- mate Prediction we currently have a job opening for the following post: Postdoc on climate change and heat stress Your main task is to calculate potential heat stress for current and future climate over Europa that will serve as a basis for assessing the impact of climate change on the health of workers. You derive complex heat indices from climate model output and validate them against observational datasets. You will further investigate the predictability of heat stress several weeks ahead on the basis of long- range weather forecasts. In close collaboration with international partners of the EU H2020 project Heat-Shield you will setup a prototype system of climate services, including an early warning system. Your work hence substantially contributes to a heat-based risk assessment for different key industries and potential productivity losses across Europe. The results will be a central basis for policy making and to plan climate adaptation measures. Your responsibilities will further include publishing results in scientific journals and reports, reporting and coordinating our contribution to the European project and presenting results at national and international conferences. -

Dealing with Inconsistent Weather Warnings: Effects on Warning Quality and Intended Actions

Research Collection Journal Article Dealing with inconsistent weather warnings: effects on warning quality and intended actions Author(s): Weyrich, Philippe; Scolobig, Anna; Patt, Anthony Publication Date: 2019-10 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000291292 Originally published in: Meteorological Applications 26(4), http://doi.org/10.1002/met.1785 Rights / License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Received: 11 July 2018 Revised: 12 December 2018 Accepted: 31 January 2019 Published on: 28 March 2019 DOI: 10.1002/met.1785 RESEARCH ARTICLE Dealing with inconsistent weather warnings: effects on warning quality and intended actions Philippe Weyrich | Anna Scolobig | Anthony Patt Climate Policy Group, Department of Environmental Systems Science, Swiss Federal In the past four decades, the private weather forecast sector has been developing Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich), Zurich, next to National Meteorological and Hydrological Services, resulting in additional Switzerland weather providers. This plurality has led to a critical duplication of public weather Correspondence warnings. For a specific event, different providers disseminate warnings that are Philippe Weyrich, Climate Policy Group, Department of Environmental Systems Science, more or less severe, or that are visualized differently, leading to inconsistent infor- Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH mation that could impact perceived warning quality and response. So far, past Zurich), 8092 Zurich, Switzerland. research has not studied the influence of inconsistent information from multiple Email: [email protected] providers. This knowledge gap is addressed here. -

List of Participants

WMO Sypmposium on Impact Based Forecasting and Warning Services Met Office, United Kingdom 2-4 December 2019 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Name Organisation 1 Abdoulaye Diakhete National Agency of Civil Aviation and Meteorology 2 Angelia Guy National Meteorological Service of Belize 3 Brian Golding Met Office Science Fellow - WMO HIWeather WCRP Impact based Forecast Team, Korea Meteorological 4 Byungwoo Jung Administration 5 Carolina Gisele Cerrudo National Meteorological Service Argentina 6 Caroline Zastiral British Red Cross 7 Catalina Jaime Red Cross Climate Centre Directorate for Space, Security and Migration Chiara Proietti 8 Disaster Risk Management Unit 9 Chris Tubbs Met Office, UK 10 Christophe Isson Météo France 11 Christopher John Noble Met Service, New Zealand 12 Dan Beardsley National Weather Service NOAA/National Weather Service, International Affairs Office 13 Daniel Muller 14 David Rogers World Bank GFDRR 15 Dr. Frederiek Sperna Weiland Deltares 16 Dr. Xu Tang Weather & Disaster Risk Reduction Service, WMO National center for hydro-meteorological forecasting, Viet Nam 17 Du Duc Tien 18 Elizabeth May Webster South African Weather Service 19 Elizabeth Page UCAR/COMET 20 Elliot Jacks NOAA 21 Gerald Fleming Public Weather Service Delivery for WMO 22 Germund Haugen Met No 23 Haleh Kootval World Bank Group 24 Helen Bye Met Office, UK 25 Helene Correa Météo-France Impact based Forecast Team, Korea Meteorological 26 Hyo Jin Han Administration Impact based Forecast Team, Korea Meteorological 27 Inhwa Ham Administration Meteorological Service -

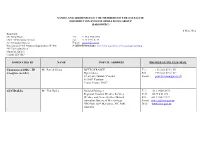

Names and Addresses of the Members of the Satellite Distribution System Operations Group (Sadisopsg)

NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF THE MEMBERS OF THE SATELLITE DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM OPERATIONS GROUP (SADISOPSG) 8 May 2014 Secretary: Mr. Greg Brock Tel: +1 514 954 8194 Chief, Meteorology Section Fax: +1 514 954 6759 Air Navigation Bureau E-mail: [email protected] International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) SADISOPSG website: http://www.icao.int/safety/meteorology/sadisopsg 999 University Street Montréal, Québec Canada H3C 5H7 NOMINATED BY NAME POSTAL ADDRESS PHONE/FAX/TELEX/E-MAIL Chairman of DMG - FP Mr. Patrick Simon METEO FRANCE Tel. : +33 5 61 07 81 50 (ex-officio member) Dprévi/Aéro Fax : +33 5 61 07 81 09 42, avenue Gustave Coriolis E-mail : [email protected] F-31057 Toulouse Cedex, France 31057 AUSTRALIA Mr. Tim Hailes National Manager Tel.: +61 3 9669 4273 Regional Aviation Weather Services Cell: +0427 840 175 Weather and Ocean Services Branch Fax: +61 3 9662 1222 Australian Bureau of Meteorology E-mail: [email protected] GPO Box 1289 Melbourne VIC 3001 Web: www.bom.gov.au Australia NOMINATED BY NAME POSTAL ADDRESS PHONE/FAX/TELEX/E-MAIL CHINA Ms. Zou Juan Engineer Tel:: + 86 10 87786828 MET Division Fax: +86 10 87786820 Air Traffic Management Bureau, CAAC E-mail: [email protected] 12 East San-huan Road Middle or [email protected] Chaoyang District, Beijing 100022 China Tel: +86 10 64598450 Ms. Lu Xin Ping Engineer E-mail: [email protected] Advisor Meteorological Center, North China ATMB Beijing Capital International Airport Beijing 100621 China CÔTE D'IVOIRE Mr. Konan Kouakou Chef du Service de l’Exploitation de la Tel.: + 225-21-21-58 90 Meteorologie or + 225 05 85 35 13 15 B.P. -

Demonstrating Forecast Capabilities for Flood Events in the Alpine Region

Veröffentlichung MeteoSchweiz Nr. 78 MAP D-PHASE: Demonstrating forecast capabilities for flood events in the Alpine region Report on the WWRP Forecast Demonstration Project D-PHASE submitted to the WWRP Joint Scientific Committee Marco Arpagaus et al. D-PHASE a WWRP Forecast Demonstration Project Veröffentlichung MeteoSchweiz Nr. 78 ISSN: 1422-1381 MAP D-PHASE: Demonstrating forecast capabilities for flood events in the Alpine region Report on the WWRP Forecast Demonstration Project D-PHASE submitted to the WWRP Joint Scientific Committee Marco Arpagaus1), Mathias W. Rotach1), Paolo Ambrosetti1), Felix Ament1), Christof Appenzeller1), Hans-Stefan Bauer2), Andreas Behrendt2), François Bouttier3), Andrea Buzzi4), Matteo Corazza5), Silvio Davolio4), Michael Denhard6), Manfred Dorninger7), Lionel Fontannaz1), Jacqueline Frick8), Felix Fundel1), Urs Germann1), Theresa Gorgas7), Giovanna Grossi9), Christoph Hegg8), Alessandro Hering1), Simon Jaun10), Christian Keil11), Mark A. Liniger1), Chiara Marsigli12), Ron McTaggart-Cowan13), Andrea Montani12), Ken Mylne14), Luca Panziera1), Roberto Ranzi9), Evelyne Richard15), Andrea Rossa16), Daniel Santos-Muñoz17), Christoph Schär10), Yann Seity3), Michael Staudinger18), Marco Stoll1), Stephan Vogt19), Hans Volkert11), André Walser1), Yong Wang18), Johannes Werhahn20), Volker Wulfmeyer2), Claudia Wunram21), and Massimiliano Zappa8). 1) Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss, Switzerland, 2) University of Hohenheim, Germany, 3) Météo-France, France, 4) Institute of Atmospheric Sciences -

Climate Services to Support Adaptation and Livelihoods

In cooperation with: Published by: Climate-Smart Land Use Insight Brief No. 3 Climate services to support adaptation and livelihoods Key Messages f Climate services – the translation, tailoring, f It is not enough to tailor climate services to a packaging and communication of climate data to specifc context; equity and inclusion require meet users’ needs – play a key role in adaptation paying attention to the differentiated needs of to climate change. For farmers, they provide vital men and women, Indigenous Peoples, ethnic information about the onset of seasons, temperature minorities, and other groups. Within a single and rainfall projections, and extreme weather community, perspectives on climate risks, events, as well as longer-term trends they need to information needs, preferences for how to receive understand to plan and adapt. climate information, and capacities to use it may vary, even just refecting the different roles that f In ASEAN Member States, where agriculture is men and women may play in agriculture. highly vulnerable to climate change, governments already recognise the importance of climate f Delivering high-quality climate services to all services. National meteorological and hydrological who need them is a signifcant challenge. Given institutes provide a growing array of data, the urgent need to adapt to climate change and disseminated online, on broadcast media and via to support the most vulnerable populations and SMS, and through agricultural extension services sectors, it is crucial to address resource gaps and and innovative programmes such as farmer feld build capacity in key institutions, so they can schools. Still, there are signifcant capacity and continue to improve climate information services resource gaps that need to be flled. -

STRATEGIE 2016–2025 FORTS D’UN OBJECTIF COMMUN Allemagne Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD)

STRATEGIE 2016–2025 FORTS D’UN OBJECTIF COMMUN Allemagne Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) Autriche Zentralanstalt für Meteorologie und Geodynamik (ZAMG) Belgique Royal Meteorological Institute of Belgium (RMI/KMI) Croatie Meteorological and Hydrological Service of Croatia (DHMZ) Danemark Danish Meteorological Institute (DMI) Espagne Agencia Estatal de Meteorología / State Meteorological Agency (AEMET) Finlande Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI) France Météo-France Grèce Hellenic National Meteorological Service (HNMS) Irlande Met Éireann Islande Icelandic Meteorological Office (IMO) Italie Ufficio Generale Spazio Aereo e Meteorologia (USAM) Luxembourg Air Navigation Administration Norvège Norwegian Meteorological Institute Pays-Bas Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) Portugall Portuguese Sea and Atmosphere Institute (IPMA) Royaume-Uni Met Office Serbie Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia Slovénie Meteorological Office, Slovenian Environment Agency (SEA) Suède Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) Suisse Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss Turquie Turkish State Meteorological Service Etats membres (janvier 2016) STRATEGIE 2016–2025 FORTS D’UN OBJECTIF COMMUN TABLE DES MATIÈRES Avant-propos . 3 Synthèse . 4 Contexte: défis et opportunités . 7 Progrès dans le domaine des sciences météorologiques . 11 Fourniture de prévisions à l’échelle mondiale . 15 Soutien en matière de calcul haute performance . 18 Appui au CEPMMT . 21 Services aux Etats membres et coopérants . 23 Conclusion -

An Ensemble of Deep Learning Models for Weather Nowcasting Based on Radar Products’ Values Prediction

applied sciences Article NowDeepN: An Ensemble of Deep Learning Models for Weather Nowcasting Based on Radar Products’ Values Prediction Gabriela Czibula 1,*,† , Andrei Mihai 1,† and Eugen Mihule¸t 2 1 Department of Computer Science, Babe¸s-BolyaiUniversity, 400084 Cluj-Napoca, Romania; [email protected] 2 Romanian National Meteorological Administration, 013686 Bucharest, Romania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +40-264-405327 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: One of the hottest topics in today’s meteorological research is weather nowcasting, which is the weather forecast for a short time period such as one to six hours. Radar is an important data source used by operational meteorologists for issuing nowcasting warnings. With the main goal of helping meteorologists in analysing radar data for issuing nowcasting warnings, we propose NowDeepN, a supervised learning based regression model which uses an ensemble of deep artificial neural networks for predicting the values for radar products at a certain time moment. The values predicted by NowDeepN may be used by meteorologists in estimating the future development of potential severe phenomena and would replace the time consuming process of extrapolating the radar echoes. NowDeepN is intended to be a proof of concept for the effectiveness of learning from radar data relevant patterns that would be useful for predicting future values for radar products based on their historical values. For assessing the performance of NowDeepN, a set of experiments on real radar data provided by the Romanian National Meteorological Administration is conducted. The impact of a data cleaning step introduced for correcting the erroneous radar products’ values is investigated both from the computational and meteorological perspectives. -

Training Inventory PRA-PTC Ext. 2 June 2019.Pdf

Institution Name Met Office Applied Sciences (UK) The Egyptian Meteorological Authority (EMA) WMO (CLW/CLPA/WCAS) in cooperation with MeteoFrance and IOC; supported by Programme for Implementing GFCS at Regional and National Scales that was funded by Environment and Climate Change Canada Met Office Applied Sciences (UK) Met Office Applied Sciences (UK) AGRHYMET AGRHYMET EUMETSAT The Egyptian Meteorological Authority (EMA) GCOS/WIGOS/GFCS/Copernicus in cooperation with UNFCCC EUMETSAT/FAO/WMO NAP-GSP (UNDP-UNEP) Met Office Applied Sciences (UK) Met Office Applied Sciences (UK) Met Office Applied Sciences (UK) Disaster Prevention Research Institute (DPRI), Kyoto University Nanjing University of Information, Science and Technology (NUIST) Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) Tokyo Climate Center (TCC) Tokyo Climate Center (TCC) Met Office Applied Sciences (UK) Met Office Applied Sciences (UK) China Meteorological Administration (CMA) Training Centre / WMO RTC Beijing WMO (CLW/CLPA/WCAS) in cooperation with RIMES and Bhutan Agriculture Research and Development Center; supported by Programme for Implementing GFCS at Regional and National Scales that was funded by Environment and Climate Change Canada Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) China Meteorological Administration (CMA) Training Centre AEMET NOAA, USIAD, WMO, CIIFEN SENAMHI/CLIMANDES AEMET AEMET AEMET The COMET Program The COMET Program The COMET Program WMO, Meteorological Service Singapore (MSS), ASEAN Specialized Meteorological Centre, funded by Environment and Climate -

Integration and Calibration of Non-Dispersive Infrared (NDIR) CO2 Low-Cost Sensors and Their Operation in a Sensor Network Covering Switzerland

Atmos. Meas. Tech., 13, 3815–3834, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-13-3815-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Integration and calibration of non-dispersive infrared (NDIR) CO2 low-cost sensors and their operation in a sensor network covering Switzerland Michael Müller1, Peter Graf1, Jonas Meyer2, Anastasia Pentina3, Dominik Brunner1, Fernando Perez-Cruz3, Christoph Hüglin1, and Lukas Emmenegger1 1Empa, Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland 2Decentlab GmbH, Dübendorf, Switzerland 3Swiss Data Science Center, Zurich, Switzerland Correspondence: Christoph Hüglin ([email protected]) Received: 29 October 2019 – Discussion started: 18 November 2019 Revised: 14 May 2020 – Accepted: 20 May 2020 – Published: 15 July 2020 Abstract. More than 300 non-dispersive infrared (NDIR) 1 Introduction CO2 low-cost sensors labelled as LP8 were integrated into sensor units and evaluated for the purpose of long-term oper- The number of available low-cost sensor types for ambient ation in the Carbosense CO2 sensor network in Switzerland. trace gas observations has increased in recent years. Fre- Prior to deployment, all sensors were calibrated in a pressure quently, these sensors are combined with wireless data trans- and climate chamber and in ambient conditions co-located fer capabilities to form a versatile measurement unit. Low- with a reference instrument. To investigate their long-term cost sensors for trace gas measurements are based on dif- performance and to test different data processing strategies, ferent working principles such as metal-oxide semiconduc- 18 sensors were deployed at five locations equipped with a tors, electrochemical cells or non-dispersive infrared detec- reference instrument after calibration. -

Corporation and Institutional Members of the AMS

corporation and institutional members of the AMS Sustaining Corporation and Institutional Members Communications Electronics Inc. Aquila, Weather Risk Management Group Computer Sciences Corporation Enterprise Electronics Corporation Concurrent Computer Corporation General Dynamics, Electronic Systems Control Data Corporation Hughes Space & Communications Company Creighton University, Atmospheric Science Program ITT Aerospace/Communications Division CSIRO Space Systems/Loral Dartmouth College Library University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, Davis Instruments Corp. National Center for Atmospheric Research Deutscher Wetterdienst WSI Corporation Digilog Instruments Dixon Weather Service Contributing Corporation and DOC/NOAA/NWS - Operational Support Facility Institutional Members DynCorp AccuWeather, Inc. EDS Corporation Advanced Forecasting Corporation Edinburgh University Library Autometric, Inc. EKO Instruments Trading Co., Ltd. Campbell Scientific, Inc. Empress Software, Inc. Global Atmospherics, Inc. Environment Canada, Mountain Weather Service Office Kavouras, Inc. Environment Canada, Science Division Sippican, Inc. ETC - Electronic Telecommunications, Inc. The Weather Channel European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Unisys Weather Information Services Satellites (EUMETSAT) Factory Mutual Engineering Corporation Corporation and Institutional Members Fernbank Science Center 3SI Finnish Meteorological Institute 26th Operational Weather Squadron Florida Institute of Technology, Evans Library 335 TRS/UOAA, Training -

Integration and Calibration of NDIR CO2 Low-Cost Sensors, And

https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-2019-408 Preprint. Discussion started: 18 November 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Integration and calibration of NDIR CO2 low-cost sensors, and their operation in a sensor network covering Switzerland Michael Mueller1, Peter Graf1, Jonas Meyer2, Anastasia Pentina3, Dominik Brunner1, Fernando Perez- Cruz3, Christoph Hüglin1, and Lukas Emmenegger1 5 1Empa, Swiss Federal Institute for Materials Science and Technology, Duebendorf, Switzerland 2Decentlab GmbH, Duebendorf, Switzerland 3Swiss Data Science Center, Zurich, Switzerland Correspondence: Michael Mueller ([email protected]) Abstract. 10 More than 300 LP8 CO2 sensors were integrated into sensor units and evaluated for the purpose of long-term operation in the Carbosense CO2 sensor network in Switzerland. Prior to deployment, all sensors were calibrated in a pressure and climate chamber, and in ambient conditions co-located with a reference instrument. To investigate their long-term performance and to test different data processing strategies, 18 sensors were deployed at five locations equipped with a reference instrument after calibration. Their accuracy during 19 to 25 months deployment was between 8 to 12 ppm. This level of accuracy requires 15 careful sensor calibration prior to deployment, continuous monitoring of the sensors, efficient data filtering, and a procedure to correct drifts and jumps in the sensor signal during operation. High relative humidity (> ~85%) impairs the LP8 measurements, and corresponding data filtering results in a significant loss during humid conditions. The LP8 sensors are not suitable for the detection of small regional gradients and long-term trends. However, with careful data processing, the sensors are able to resolve CO2 changes and differences with a magnitude larger than about 20 ppm.