Climate Services to Support Adaptation and Livelihoods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meteoswiss Good to Know Postdoc on Climate Change and Heat Stress

Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss MeteoSwiss Good to know The Swiss Federal Office for Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss is the Swiss National Weather Service. We record, monitor and forecast weather and climate in Switzerland and thus make a sus- tainable contribution to the well-being of the community and to the benefit of industry, science and the environment. The Climate Department carries out statistical analyses of observed and modelled cli- mate data and is responsible for providing the results for users and customers. Within the team Cli- mate Prediction we currently have a job opening for the following post: Postdoc on climate change and heat stress Your main task is to calculate potential heat stress for current and future climate over Europa that will serve as a basis for assessing the impact of climate change on the health of workers. You derive complex heat indices from climate model output and validate them against observational datasets. You will further investigate the predictability of heat stress several weeks ahead on the basis of long- range weather forecasts. In close collaboration with international partners of the EU H2020 project Heat-Shield you will setup a prototype system of climate services, including an early warning system. Your work hence substantially contributes to a heat-based risk assessment for different key industries and potential productivity losses across Europe. The results will be a central basis for policy making and to plan climate adaptation measures. Your responsibilities will further include publishing results in scientific journals and reports, reporting and coordinating our contribution to the European project and presenting results at national and international conferences. -

Worldwide Marine Radiofacsimile Broadcast Schedules

WORLDWIDE MARINE RADIOFACSIMILE BROADCAST SCHEDULES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL OCEANIC and ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE January 14, 2021 INTRODUCTION Ships....The U.S. Voluntary Observing Ship (VOS) program needs your help! If your ship is not participating in this worthwhile international program, we urge you to join. Remember, the meteorological agencies that do the weather forecasting cannot help you without input from you. ONLY YOU KNOW THE WEATHER AT YOUR POSITION!! Please report the weather at 0000, 0600, 1200, and 1800 UTC as explained in the National Weather Service Observing Handbook No. 1 for Marine Surface Weather Observations. Within 300 nm of a named hurricane, typhoon or tropical storm, or within 200 nm of U.S. or Canadian waters, also report the weather at 0300, 0900, 1500, and 2100 UTC. Your participation is greatly appreciated by all mariners. For assistance, contact a Port Meteorological Officer (PMO), who will come aboard your vessel and provide all the information you need to observe, code and transmit weather observations. This publication is made available via the Internet at: https://weather.gov/marine/media/rfax.pdf The following webpage contains information on the dissemination of U.S. National Weather Service marine products including radiofax, such as frequency and scheduling information as well as links to products. A listing of other recommended webpages may be found in the Appendix. https://weather.gov/marine This PDF file contains links to http pages and FTPMAIL commands. The links may not be compatible with all PDF readers and e-mail systems. The Internet is not part of the National Weather Service's operational data stream and should never be relied upon as a means to obtain the latest forecast and warning data. -

December 2013 from the Editor

Volume 57, Number 3 December 2013 From the Editor Paula M. Rychtar MARINERS WEATHER LOG ISSN 0025-3367 Greetings and welcome to the December issue of the Mariners Weather Log. This issue U.S. Department of Commerce ushers in the Holiday Season and the end of another year as well as the end of another hurricane season. I hope this issue finds all in good spirits, safe and sound. Dr. Kathryn D. Sullivan Under Secretary of Commerce for If you read my last editors note, I touched on the importance of marine weather observations Oceans & Atmosphere & NOAA Administrator for the accuracy of forecasts, environmental studies and improving guidance towards better Acting Administrator hurricane forecast tracks; this in turn is part of the equation for seasonal hurricane outlooks. Now that hurricane season is finally over, we can reflect on hurricane season 2013. In May NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE of 2013, the initial hurricane outlook that was issued turned out extremely different from the Dr. Louis Uccellini actual outcome. NOAA is continuously dealing with the cause and effect of climate change NOAA Assistant Administrator for and predicting hurricane seasons is no different. Looking back at 2013, it was predicted Weather Services that our season would be “active or extremely active”. We were expected a 70 percent likelihood of 13 to 20 named storms, of which 7 to 11 could become hurricanes, including EDITORIAL SUPERVISOR 3 to 6 major hurricanes. As it turns out, this year was the sixth least active season in the Paula M. Rychtar Atlantic Ocean since 1950. 13 named storms formed in the Atlantic and only two, Ingrid LAYOUT AND DESIGN and Humberto, became hurricanes which neither achieved category 3 status or higher. -

Dealing with Inconsistent Weather Warnings: Effects on Warning Quality and Intended Actions

Research Collection Journal Article Dealing with inconsistent weather warnings: effects on warning quality and intended actions Author(s): Weyrich, Philippe; Scolobig, Anna; Patt, Anthony Publication Date: 2019-10 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000291292 Originally published in: Meteorological Applications 26(4), http://doi.org/10.1002/met.1785 Rights / License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Received: 11 July 2018 Revised: 12 December 2018 Accepted: 31 January 2019 Published on: 28 March 2019 DOI: 10.1002/met.1785 RESEARCH ARTICLE Dealing with inconsistent weather warnings: effects on warning quality and intended actions Philippe Weyrich | Anna Scolobig | Anthony Patt Climate Policy Group, Department of Environmental Systems Science, Swiss Federal In the past four decades, the private weather forecast sector has been developing Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich), Zurich, next to National Meteorological and Hydrological Services, resulting in additional Switzerland weather providers. This plurality has led to a critical duplication of public weather Correspondence warnings. For a specific event, different providers disseminate warnings that are Philippe Weyrich, Climate Policy Group, Department of Environmental Systems Science, more or less severe, or that are visualized differently, leading to inconsistent infor- Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH mation that could impact perceived warning quality and response. So far, past Zurich), 8092 Zurich, Switzerland. research has not studied the influence of inconsistent information from multiple Email: [email protected] providers. This knowledge gap is addressed here. -

List of Participants

WMO Sypmposium on Impact Based Forecasting and Warning Services Met Office, United Kingdom 2-4 December 2019 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Name Organisation 1 Abdoulaye Diakhete National Agency of Civil Aviation and Meteorology 2 Angelia Guy National Meteorological Service of Belize 3 Brian Golding Met Office Science Fellow - WMO HIWeather WCRP Impact based Forecast Team, Korea Meteorological 4 Byungwoo Jung Administration 5 Carolina Gisele Cerrudo National Meteorological Service Argentina 6 Caroline Zastiral British Red Cross 7 Catalina Jaime Red Cross Climate Centre Directorate for Space, Security and Migration Chiara Proietti 8 Disaster Risk Management Unit 9 Chris Tubbs Met Office, UK 10 Christophe Isson Météo France 11 Christopher John Noble Met Service, New Zealand 12 Dan Beardsley National Weather Service NOAA/National Weather Service, International Affairs Office 13 Daniel Muller 14 David Rogers World Bank GFDRR 15 Dr. Frederiek Sperna Weiland Deltares 16 Dr. Xu Tang Weather & Disaster Risk Reduction Service, WMO National center for hydro-meteorological forecasting, Viet Nam 17 Du Duc Tien 18 Elizabeth May Webster South African Weather Service 19 Elizabeth Page UCAR/COMET 20 Elliot Jacks NOAA 21 Gerald Fleming Public Weather Service Delivery for WMO 22 Germund Haugen Met No 23 Haleh Kootval World Bank Group 24 Helen Bye Met Office, UK 25 Helene Correa Météo-France Impact based Forecast Team, Korea Meteorological 26 Hyo Jin Han Administration Impact based Forecast Team, Korea Meteorological 27 Inhwa Ham Administration Meteorological Service -

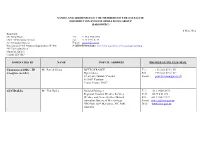

Names and Addresses of the Members of the Satellite Distribution System Operations Group (Sadisopsg)

NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF THE MEMBERS OF THE SATELLITE DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM OPERATIONS GROUP (SADISOPSG) 8 May 2014 Secretary: Mr. Greg Brock Tel: +1 514 954 8194 Chief, Meteorology Section Fax: +1 514 954 6759 Air Navigation Bureau E-mail: [email protected] International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) SADISOPSG website: http://www.icao.int/safety/meteorology/sadisopsg 999 University Street Montréal, Québec Canada H3C 5H7 NOMINATED BY NAME POSTAL ADDRESS PHONE/FAX/TELEX/E-MAIL Chairman of DMG - FP Mr. Patrick Simon METEO FRANCE Tel. : +33 5 61 07 81 50 (ex-officio member) Dprévi/Aéro Fax : +33 5 61 07 81 09 42, avenue Gustave Coriolis E-mail : [email protected] F-31057 Toulouse Cedex, France 31057 AUSTRALIA Mr. Tim Hailes National Manager Tel.: +61 3 9669 4273 Regional Aviation Weather Services Cell: +0427 840 175 Weather and Ocean Services Branch Fax: +61 3 9662 1222 Australian Bureau of Meteorology E-mail: [email protected] GPO Box 1289 Melbourne VIC 3001 Web: www.bom.gov.au Australia NOMINATED BY NAME POSTAL ADDRESS PHONE/FAX/TELEX/E-MAIL CHINA Ms. Zou Juan Engineer Tel:: + 86 10 87786828 MET Division Fax: +86 10 87786820 Air Traffic Management Bureau, CAAC E-mail: [email protected] 12 East San-huan Road Middle or [email protected] Chaoyang District, Beijing 100022 China Tel: +86 10 64598450 Ms. Lu Xin Ping Engineer E-mail: [email protected] Advisor Meteorological Center, North China ATMB Beijing Capital International Airport Beijing 100621 China CÔTE D'IVOIRE Mr. Konan Kouakou Chef du Service de l’Exploitation de la Tel.: + 225-21-21-58 90 Meteorologie or + 225 05 85 35 13 15 B.P. -

Demonstrating Forecast Capabilities for Flood Events in the Alpine Region

Veröffentlichung MeteoSchweiz Nr. 78 MAP D-PHASE: Demonstrating forecast capabilities for flood events in the Alpine region Report on the WWRP Forecast Demonstration Project D-PHASE submitted to the WWRP Joint Scientific Committee Marco Arpagaus et al. D-PHASE a WWRP Forecast Demonstration Project Veröffentlichung MeteoSchweiz Nr. 78 ISSN: 1422-1381 MAP D-PHASE: Demonstrating forecast capabilities for flood events in the Alpine region Report on the WWRP Forecast Demonstration Project D-PHASE submitted to the WWRP Joint Scientific Committee Marco Arpagaus1), Mathias W. Rotach1), Paolo Ambrosetti1), Felix Ament1), Christof Appenzeller1), Hans-Stefan Bauer2), Andreas Behrendt2), François Bouttier3), Andrea Buzzi4), Matteo Corazza5), Silvio Davolio4), Michael Denhard6), Manfred Dorninger7), Lionel Fontannaz1), Jacqueline Frick8), Felix Fundel1), Urs Germann1), Theresa Gorgas7), Giovanna Grossi9), Christoph Hegg8), Alessandro Hering1), Simon Jaun10), Christian Keil11), Mark A. Liniger1), Chiara Marsigli12), Ron McTaggart-Cowan13), Andrea Montani12), Ken Mylne14), Luca Panziera1), Roberto Ranzi9), Evelyne Richard15), Andrea Rossa16), Daniel Santos-Muñoz17), Christoph Schär10), Yann Seity3), Michael Staudinger18), Marco Stoll1), Stephan Vogt19), Hans Volkert11), André Walser1), Yong Wang18), Johannes Werhahn20), Volker Wulfmeyer2), Claudia Wunram21), and Massimiliano Zappa8). 1) Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss, Switzerland, 2) University of Hohenheim, Germany, 3) Météo-France, France, 4) Institute of Atmospheric Sciences -

Climate Change Scenarios in the Philippines

Climate change scenarios in the Philippines (COVER PAGE) February 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 How the climate change scenarios were developed? 5 1.2 How were the downscaling techniques applied using the PRECIS model simulations or run? 8 1.3 How were uncertainties in the modeling simulations dealt with? 9 1.4 What is the level of confidence in the climate projections? 11 1.5 What are the possible applications of these model-generated climate scenarios? 12 CHAPTER 2 OBSERVED CLIMATE DATA 13 2.1 Current climate trends in the Philippines 16 CHAPTER 3 CLIMATE PROJECTIONS IN THE PHILIPPINES 22 3.1 Seasonal Temperature Change 25 3.2 Seasonal Rainfall Change 25 3.3 Extreme Temperature Events 26 3.4 Extreme Rainfall Events 27 3.5 Regional Projections 28 3.5.1 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in Region 1 29 3.5.2 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in Region 2 30 3.5.3 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in CAR 31 3.5.4 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in Region 3 32 3.5.5 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in Region 4A 33 3.5.6 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in Region 4B 34 3.5.7 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in NCR 35 3.5.8 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in Region 5 36 3.5.9 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in Region 6 37 3.5.10 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in Region 7 38 3.5.11 Climate Projections in 2020 & 2050 in provinces in Region 8 -

WMO Guidelines on Multi-Hazard Impact-Based Forecast and Warning Services

WMO Guidelines on Multi-hazard Impact-based Forecast and Warning Services WMO-No. 1150 WMO Guidelines on Multi-hazard Impact-based Forecast and Warning Services 2015 WMO-No. 1150 EDITORIAL NOTE METEOTERM, the WMO terminology database, may be consulted at http://www.wmo.int/pages/ prog/lsp/meteoterm_wmo_en.html. Acronyms may also be found at http://www.wmo.int/pages/ themes/acronyms/index_en.html. The WMO Public Weather Services Programme would like to take this opportunity to thank the authors who contributed to this publication: Gerald Fleming (Met Éireann, The Irish Meteorological Service); David Rogers (World Bank/Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery); Paul Davies (Met Office, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland); Elliott Jacks (National Weather Service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States of America); Jennifer Ann Milton (Environment Canada); Cyrille Honoré (Météo-France); Lap Shun Lee (Hong Kong Observatory, Hong Kong, China); John Bally (Bureau of Meteorology, Australia); WANG Zhihua (China Meteorological Administration); Vlasta Tutis (Meteorological and Hydrological Service of Croatia); and Premchand Goolaup (Mauritius Meteorological Services). WMO-No. 1150 © World Meteorological Organization, 2015 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Editorial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chairperson, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis, avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 84 03 P.O. -

CNS/MET SG/14-WP/36 Agenda Item 8 (1) 19/07/10 International Civil Aviation Organization

CNS/MET SG/14-WP/36 Agenda Item 8 (1) 19/07/10 International Civil Aviation Organization FOURTEENTH MEETING OF THE COMMUNICATIONS/NAVIGATION/SURVEILL ANCE AND METEOROLOGY SUB-GROUP OF APANPIRG (CNS/MET SG/14) Jakarta, Indonesia, 19 – 22 July 2010 Agenda Item 8: Regional Implementation of World Area Forecast System (WAFS) 1) implementation issues associated with cessation of ISCS-G2 WAFS INTERNET FILE SERVER (WIFS) – UPDATE (Presented by the United States of America) SUMMARY The WAFC Washington Provider State implemented the World Area Forecast System (WAFS) Internet File Server (WIFS) in March 2010. It is the replacement for the ISCS satellite broadcast, which will be terminated 30 June 2012. ISCS user States must switch to WIFS to have access to OPMET and WAFS products after June 30, 2012. This paper relates to: Strategic Objectives: A. Safety – Enhance global civil aviation safety D. Efficiency – Enhance the efficiency of aviation operations Global Plan Initiatives: GPI-18 Aeronautical information GPI-19 Meteorological Systems 1. Introduction 1.1 The Sub Group will recall that the WAFS Internet File Server (WIFS) was first introduced to the CNS/MET SG at Meeting 13 in Working Paper 29. From that paper the following draft conclusion was adopted: Draft Conclusion 13/31 – Extension of the ISCS-G2 and the implementation of the WAFS Internet file server (WIFS) That, WAFC Washington Provider State advise the ISCS user States about its intentions to: CNS/MET SG/14-WP/36 - 2 - Agenda Item 8 (1) 19/07/10 a) continue to work on extending the current ISCS-G2 service through 30 June 2012 to allow users sufficient time for transition to replacement services; and b) provide an operational WAFS Internet File Server (WIFS) by March 2010. -

April 2012 2 April 2012 ~ Mariners Weather Log See These Web Pages for Further Links

Volume 56, Number 1 April 2012 From the Editor Paula Rychtar Paula here and I have the “conn”. M W L Welcome to my fi rst issue of the Mariners Weather Log. I have some great ISSN 0025-3367 ideas for our magazine and I do encourage input from all of you. First, I U.S. Department of Commerce would like to give a loud and enthusiastic welcome aboard to our new Port Meteorological Offi cer, David Jones. Dave will be the new PMO for the New Jane Lubchenco Ph.D. Orleans/Gulf Coast area; you can read his bio on Page 8. Dave will begin his Under Secretary of Commerce for responsibilities in March. Oceans and Atmosphere In this issue, we need to say farewell to one of our dear friends and a strong National Weather Service advocate of the U.S. VOS program, Dr. Bill Burnett. Dr. Bill Burnett has been Dr. John "Jack" L. Hayes selected as the new Technical Director of Commander, Naval Meteorology NOAA Assistant Administrator for and Oceanography Command (CNMOC). This is a tremendous and well- Weather Services deserved accomplishment for Bill, and I know that we are all very proud of him and happy for him. Bill’s departure is a loss to NDBC, VOS as well as Editorial Supervisor the Joint Technical Commission for Oceanography and Marine Meteorology Paula M. Rychtar (JCOMM). It will be very diffi cult to replace him. You can read his farewell story on page 8. Layout and Design Leigh Ellis I hope you enjoy our featured cover story, Observer-based Whale Shark Research in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. -

The Philippine National Meteorological & Hydrological

TheThe PhilippinePhilippine NationalNational MeteorologicalMeteorological && HydrologicalHydrological ServicesServices (NMHS):(NMHS): ItsIts Products,Products, ServicesServices andand NewNew InitiativesInitiatives forfor SustainableSustainable DevelopmentDevelopment A paper presented to the UN-Austria-ESA Symposium on Space Tools & Solutions for Monitoring the Atmosphere in Support of Sustainable Development Carina G. Lao Philippines “Tracking the sky …helping the country ” PUBLICPUBLIC WEATHERWEATHER SERVICESSERVICES Topic Outline 1. PAGASA - the nation’s public weather service provider a. Legal Mandate, Mission, Vision, Mandated Functions b. Services, Specialized Products and Information c. Range of Techniques for the services’ provision d. End-users, Beneficiaries e. Policies, Challenges and Directions “Tracking the sky …helping the country ” PUBLICPUBLIC WEATHERWEATHER SERVICESSERVICES Topic Outline 2. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) a. Main Purpose of WMO b. Role of National Meteorological and Hydrological Services c. Overall Objectives of WMO d. WMO Programmes “Tracking the sky …helping the country ” PUBLICPUBLIC WEATHERWEATHER SERVICESSERVICES Topic Outline 3. Conduct of/Attendance to Seminar/Conference a. National Seminar Workshop in the Phils b. International Conference in Madrid c. Purpose of the Conference d. Hydrometeorological & Related Influence on Social & Economical e. Major Economic Sectoral Groups f. Principal Goal/Recmmendations/Action Plans PUBLICPUBLIC WEATHERWEATHER SERVICESSERVICES Topic Outline 4. Programs/Projects/Initiatives