Dealing with Inconsistent Weather Warnings: Effects on Warning Quality and Intended Actions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meteoswiss Good to Know Postdoc on Climate Change and Heat Stress

Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss MeteoSwiss Good to know The Swiss Federal Office for Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss is the Swiss National Weather Service. We record, monitor and forecast weather and climate in Switzerland and thus make a sus- tainable contribution to the well-being of the community and to the benefit of industry, science and the environment. The Climate Department carries out statistical analyses of observed and modelled cli- mate data and is responsible for providing the results for users and customers. Within the team Cli- mate Prediction we currently have a job opening for the following post: Postdoc on climate change and heat stress Your main task is to calculate potential heat stress for current and future climate over Europa that will serve as a basis for assessing the impact of climate change on the health of workers. You derive complex heat indices from climate model output and validate them against observational datasets. You will further investigate the predictability of heat stress several weeks ahead on the basis of long- range weather forecasts. In close collaboration with international partners of the EU H2020 project Heat-Shield you will setup a prototype system of climate services, including an early warning system. Your work hence substantially contributes to a heat-based risk assessment for different key industries and potential productivity losses across Europe. The results will be a central basis for policy making and to plan climate adaptation measures. Your responsibilities will further include publishing results in scientific journals and reports, reporting and coordinating our contribution to the European project and presenting results at national and international conferences. -

Worldwide Marine Radiofacsimile Broadcast Schedules

WORLDWIDE MARINE RADIOFACSIMILE BROADCAST SCHEDULES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL OCEANIC and ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE January 14, 2021 INTRODUCTION Ships....The U.S. Voluntary Observing Ship (VOS) program needs your help! If your ship is not participating in this worthwhile international program, we urge you to join. Remember, the meteorological agencies that do the weather forecasting cannot help you without input from you. ONLY YOU KNOW THE WEATHER AT YOUR POSITION!! Please report the weather at 0000, 0600, 1200, and 1800 UTC as explained in the National Weather Service Observing Handbook No. 1 for Marine Surface Weather Observations. Within 300 nm of a named hurricane, typhoon or tropical storm, or within 200 nm of U.S. or Canadian waters, also report the weather at 0300, 0900, 1500, and 2100 UTC. Your participation is greatly appreciated by all mariners. For assistance, contact a Port Meteorological Officer (PMO), who will come aboard your vessel and provide all the information you need to observe, code and transmit weather observations. This publication is made available via the Internet at: https://weather.gov/marine/media/rfax.pdf The following webpage contains information on the dissemination of U.S. National Weather Service marine products including radiofax, such as frequency and scheduling information as well as links to products. A listing of other recommended webpages may be found in the Appendix. https://weather.gov/marine This PDF file contains links to http pages and FTPMAIL commands. The links may not be compatible with all PDF readers and e-mail systems. The Internet is not part of the National Weather Service's operational data stream and should never be relied upon as a means to obtain the latest forecast and warning data. -

NOTICE: This Publication Is Available At

Department of Commerce • National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration • National Weather Service NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE INSTRUCTION 10-807 OCTOBER 5, 2017 Operations and Services Aviation Weather Services, NWSPD 10-8 INTERNATIONAL SERVICE AGREEMENTS NOTICE: This publication is available at: http://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/. OPR: W/AFS24 (M. Graf) Certified by: W/AFS24 (W. Bauman) Type of Issuance: Routine SUMMARY OF REVISIONS: This directive supersedes NWSI 10-807, “International Service Agreements,” dated May 19, 2009. Changes were made to reflect the NWS Headquarters reorganization effective on April 1, 2015. No content changes were made. Signed 9/21/2017 Andrew D. Stern Date Director Analyze, Forecast, and Support Office NWSI 10-807 OCTOBER 5, 2017 International Service Agreements Table of Contents Page 1. Purpose. ..................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Background. ............................................................................................................................... 2 3. Definition of Unique Terms. ................................................................................................................ 3 4. General ............................................................................................................................................ 3 5. Correspondence with Foreign Meteorological Services. ................................................................. 4 6. Services Provided. -

List of Participants

WMO Sypmposium on Impact Based Forecasting and Warning Services Met Office, United Kingdom 2-4 December 2019 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Name Organisation 1 Abdoulaye Diakhete National Agency of Civil Aviation and Meteorology 2 Angelia Guy National Meteorological Service of Belize 3 Brian Golding Met Office Science Fellow - WMO HIWeather WCRP Impact based Forecast Team, Korea Meteorological 4 Byungwoo Jung Administration 5 Carolina Gisele Cerrudo National Meteorological Service Argentina 6 Caroline Zastiral British Red Cross 7 Catalina Jaime Red Cross Climate Centre Directorate for Space, Security and Migration Chiara Proietti 8 Disaster Risk Management Unit 9 Chris Tubbs Met Office, UK 10 Christophe Isson Météo France 11 Christopher John Noble Met Service, New Zealand 12 Dan Beardsley National Weather Service NOAA/National Weather Service, International Affairs Office 13 Daniel Muller 14 David Rogers World Bank GFDRR 15 Dr. Frederiek Sperna Weiland Deltares 16 Dr. Xu Tang Weather & Disaster Risk Reduction Service, WMO National center for hydro-meteorological forecasting, Viet Nam 17 Du Duc Tien 18 Elizabeth May Webster South African Weather Service 19 Elizabeth Page UCAR/COMET 20 Elliot Jacks NOAA 21 Gerald Fleming Public Weather Service Delivery for WMO 22 Germund Haugen Met No 23 Haleh Kootval World Bank Group 24 Helen Bye Met Office, UK 25 Helene Correa Météo-France Impact based Forecast Team, Korea Meteorological 26 Hyo Jin Han Administration Impact based Forecast Team, Korea Meteorological 27 Inhwa Ham Administration Meteorological Service -

HURRICANE TEDDY (AL202020) 12–23 September 2020

r d NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT HURRICANE TEDDY (AL202020) 12–23 September 2020 Eric S. Blake National Hurricane Center 28 April 2021 NASA TERRA MODIS VISIBLE SATELLITE IMAGE OF HURRICANE TEDDY AT 1520 UTC 22 SEPTEMBER 2020. Teddy was a classic, long-lived Cape Verde category 4 hurricane on the Saffir- Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. It passed northeast of the Leeward Islands and became extremely large over the central Atlantic, eventually making landfall in Nova Scotia as a 55-kt extratropical cyclone. There were 3 direct deaths in the United States due to rip currents. Hurricane Teddy 2 Hurricane Teddy 12–23 SEPTEMBER 2020 SYNOPTIC HISTORY Teddy originated from a strong tropical wave that moved off the west coast of Africa on 10 September, accompanied by a large area of deep convection. The wave was experiencing moderate northeasterly shear, but a broad area of low pressure and banding features still formed on 11 September a few hundred n mi southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. Convection decreased late that day, as typically happens in the evening diurnal minimum period, but increased early on 12 September. This convection led to the development of a well-defined surface center, confirmed by scatterometer data, and the formation of a tropical depression near 0600 UTC 12 September about 500 n mi southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. The “best track” chart of the tropical cyclone’s path is given in Fig. 1, with the wind and pressure histories shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The best track positions and intensities are listed in Table 1.1 After the depression formed, further development was slow during the next couple of days due to a combination of northeasterly shear, dry air in the mid-levels and the large size and radius of maximum winds of the system. -

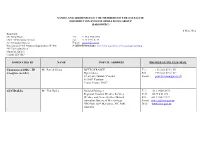

Names and Addresses of the Members of the Satellite Distribution System Operations Group (Sadisopsg)

NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF THE MEMBERS OF THE SATELLITE DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM OPERATIONS GROUP (SADISOPSG) 8 May 2014 Secretary: Mr. Greg Brock Tel: +1 514 954 8194 Chief, Meteorology Section Fax: +1 514 954 6759 Air Navigation Bureau E-mail: [email protected] International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) SADISOPSG website: http://www.icao.int/safety/meteorology/sadisopsg 999 University Street Montréal, Québec Canada H3C 5H7 NOMINATED BY NAME POSTAL ADDRESS PHONE/FAX/TELEX/E-MAIL Chairman of DMG - FP Mr. Patrick Simon METEO FRANCE Tel. : +33 5 61 07 81 50 (ex-officio member) Dprévi/Aéro Fax : +33 5 61 07 81 09 42, avenue Gustave Coriolis E-mail : [email protected] F-31057 Toulouse Cedex, France 31057 AUSTRALIA Mr. Tim Hailes National Manager Tel.: +61 3 9669 4273 Regional Aviation Weather Services Cell: +0427 840 175 Weather and Ocean Services Branch Fax: +61 3 9662 1222 Australian Bureau of Meteorology E-mail: [email protected] GPO Box 1289 Melbourne VIC 3001 Web: www.bom.gov.au Australia NOMINATED BY NAME POSTAL ADDRESS PHONE/FAX/TELEX/E-MAIL CHINA Ms. Zou Juan Engineer Tel:: + 86 10 87786828 MET Division Fax: +86 10 87786820 Air Traffic Management Bureau, CAAC E-mail: [email protected] 12 East San-huan Road Middle or [email protected] Chaoyang District, Beijing 100022 China Tel: +86 10 64598450 Ms. Lu Xin Ping Engineer E-mail: [email protected] Advisor Meteorological Center, North China ATMB Beijing Capital International Airport Beijing 100621 China CÔTE D'IVOIRE Mr. Konan Kouakou Chef du Service de l’Exploitation de la Tel.: + 225-21-21-58 90 Meteorologie or + 225 05 85 35 13 15 B.P. -

Demonstrating Forecast Capabilities for Flood Events in the Alpine Region

Veröffentlichung MeteoSchweiz Nr. 78 MAP D-PHASE: Demonstrating forecast capabilities for flood events in the Alpine region Report on the WWRP Forecast Demonstration Project D-PHASE submitted to the WWRP Joint Scientific Committee Marco Arpagaus et al. D-PHASE a WWRP Forecast Demonstration Project Veröffentlichung MeteoSchweiz Nr. 78 ISSN: 1422-1381 MAP D-PHASE: Demonstrating forecast capabilities for flood events in the Alpine region Report on the WWRP Forecast Demonstration Project D-PHASE submitted to the WWRP Joint Scientific Committee Marco Arpagaus1), Mathias W. Rotach1), Paolo Ambrosetti1), Felix Ament1), Christof Appenzeller1), Hans-Stefan Bauer2), Andreas Behrendt2), François Bouttier3), Andrea Buzzi4), Matteo Corazza5), Silvio Davolio4), Michael Denhard6), Manfred Dorninger7), Lionel Fontannaz1), Jacqueline Frick8), Felix Fundel1), Urs Germann1), Theresa Gorgas7), Giovanna Grossi9), Christoph Hegg8), Alessandro Hering1), Simon Jaun10), Christian Keil11), Mark A. Liniger1), Chiara Marsigli12), Ron McTaggart-Cowan13), Andrea Montani12), Ken Mylne14), Luca Panziera1), Roberto Ranzi9), Evelyne Richard15), Andrea Rossa16), Daniel Santos-Muñoz17), Christoph Schär10), Yann Seity3), Michael Staudinger18), Marco Stoll1), Stephan Vogt19), Hans Volkert11), André Walser1), Yong Wang18), Johannes Werhahn20), Volker Wulfmeyer2), Claudia Wunram21), and Massimiliano Zappa8). 1) Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology MeteoSwiss, Switzerland, 2) University of Hohenheim, Germany, 3) Météo-France, France, 4) Institute of Atmospheric Sciences -

Papua New Guinea Meteorological Service Country Report

PAPUA NEW GUINEA METEOROLOGICAL SERVICE COUNTRY REPORT Reporting on National Priority Actions of the Pacific Islands Meteorological Strategy (PIMS) 2012-2021 This Report is presented to the Fourth Pacific Meteorological Council (PMC-4) Meeting held in Honiara from 14-18 August 2017 SAMUEL MAIHA [email protected] Table of Contents 1.0 Summary .................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 Background Information .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Institutional Setup ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 [This subsection will cover an UPDATE of the brief on the institutional arrangement of the NMHS as well as its linkages to the Ministry. Make mention of the legislation or any Acts to support the NMS.] .................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Staffing ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 -

Climate Services to Support Adaptation and Livelihoods

In cooperation with: Published by: Climate-Smart Land Use Insight Brief No. 3 Climate services to support adaptation and livelihoods Key Messages f Climate services – the translation, tailoring, f It is not enough to tailor climate services to a packaging and communication of climate data to specifc context; equity and inclusion require meet users’ needs – play a key role in adaptation paying attention to the differentiated needs of to climate change. For farmers, they provide vital men and women, Indigenous Peoples, ethnic information about the onset of seasons, temperature minorities, and other groups. Within a single and rainfall projections, and extreme weather community, perspectives on climate risks, events, as well as longer-term trends they need to information needs, preferences for how to receive understand to plan and adapt. climate information, and capacities to use it may vary, even just refecting the different roles that f In ASEAN Member States, where agriculture is men and women may play in agriculture. highly vulnerable to climate change, governments already recognise the importance of climate f Delivering high-quality climate services to all services. National meteorological and hydrological who need them is a signifcant challenge. Given institutes provide a growing array of data, the urgent need to adapt to climate change and disseminated online, on broadcast media and via to support the most vulnerable populations and SMS, and through agricultural extension services sectors, it is crucial to address resource gaps and and innovative programmes such as farmer feld build capacity in key institutions, so they can schools. Still, there are signifcant capacity and continue to improve climate information services resource gaps that need to be flled. -

Objective Mixed and Manually Controlled Data Base OMG

EMS Annual Meeting Abstracts, 9th UROPEAN EMS Annual Meeting 9TH E ON Vol. 6, EMS2009-115, 2009 CONFERENCE Applications of Meteorology 9th EMS / 9th ECAM High resolution meteorology © Author(s) 2009 - applications and services Objective Mixed and Manually Controlled Data Base OMG T. Kratzsch and Dr. M. Rohn German National Weather Service, Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD), Offenbach, Germany ([email protected], 069-8062 2254 Many customers of Deutscher Wetterdienst get forecast products (different deterministic meteorological pa- rameters) as so-called Point-Time-Prognoses (PTPs). There’s the need for data of high resolution in space (several kilometers, cities) and time (hourly up to forecast-day 7, updated each hour). Those interpretations of the numerical models have been designed by different methods, called DMO, Model Output Statistics (MOS), Kalman filtering. Because of different model results and different methods there are between five and ten different PTPs for the same location. While a forecaster, based on his experience, can choose between that different interpretations, an automatic customers supply can’t do so. Because updates of those interpretations are only available for each new model run, there’s also the need for more actual forecast data, using nowcasting methods as well as controlling and modifying mechanisms for the forecasters. A process “Objective Optimization” has been implemented which automatically combines the available PTP data, nowcasting products and observations at all required locations. A frequent update of this optimization process every 30 minutes ensures that the OOG is based on the latest available model, nowcasting, and observational information. The resulting so-called “Objectively Optimized Guidance” (OOG) passes an interactive quality control step to produce a “Man Modified output” (MMO). -

Service Assessment Hurricane Irene, August

Service Assessment Hurricane Irene, August 21–30, 2011 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service Silver Spring, Maryland Cover Photographs: Top Left - NOAA GOES 13 visible image of Hurricane Irene taken at 12:32 UTC (8:32 a.m. EDT) on August 27, 2011, as it was moving northward along the east coast. Map of total storm rainfall for Hurricane Irene (NCEP/HPC) overlaid with photos of Hurricane Irene’s impacts. Clockwise from top right: • Damage to bridge over the Pemigewasset River/East Branch in Lincoln, NH (NH DOT) • Trees across road and utility lines in Guilford, CT (CT DEP) • Damage to homes from storm surge at Cosey Beach, East Haven, CT (CT DEP) • Flooding of Delaware River closes Rt. 29 in Trenton, NJ (State of New Jersey, Office of the Governor) • Damage from storm surge on North Carolina’s Outer Banks (USGS) • Damage to home from an EF1 tornado in Lewes, DE (Sussex County, DE EOC) • River flooding on Schoharie Creek near Lexington, NY (USGS) • Flood damage to historic covered bridge and road in Quechee, VT (FEMA) ii Service Assessment Hurricane Irene, August 21–30, 2011 September 2012 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Dr. Jane Lubchenco, Administrator National Weather Service Laura Furgione, Acting Assistant Administrator for Weather Services iii Preface On August 21-29, 2011, Hurricane Irene left a devastating imprint on the Caribbean and U.S. East Coast. The storm took the lives of more than 40 people, caused an estimated $6.5 billion in damages, unleashed major flooding, downed trees and power lines, and forced road closures, evacuations, and major rescue efforts. -

Meteorological Office

RURAL AFFAIRS AND ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE SUBMISSION FROM THE METEOROLOGICAL OFFICE Introduction The Met Office is a Trading Fund Agency owned by MOD. It is a world leading organisation, both in the field of weather forecasting and climate prediction1, operating on a 24/7 basis with the highest standards of operational resilience. Responsible for providing forecasts on all timescales (from an hour ahead to 100+ yrs), the Met Office is uniquely positioned to support the Scottish Government’s response to changing incidence of severe weather events due to climate change. It is responsible - through its Public Weather Service - for providing the National Severe Weather Warning Service (NSWWS) for the whole of the UK. Unlike many other nations in Europe where weather and flood forecasting and warning are integrated into a single meteorological and hydrological agency, the Met Office has no direct responsibility for river or coastal flood forecasting. In Scotland, river (fluvial) flood forecasting is provided by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), with whom the Met Office works closely, providing daily rainfall and general weather forecast inputs, together with rainfall radar data for the Flooding Early Warning System (FEWS). The Met Office also provides storm tide and surge warnings for the coastal flood watch service introduced by SEPA in 2007. The historical data required by SEPA to develop an effective coastal flood warning system is not available though it is understood that investment in this initiative would allow development of the modelling capability required. Currently no agency provides warnings of localised flash flooding (also known as pluvial flooding), although the Met Office will give an indication of such risks alongside its weather forecasts.