On .Social Organization Department of Sociology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lipset 2020 Program FINAL V4.Indd

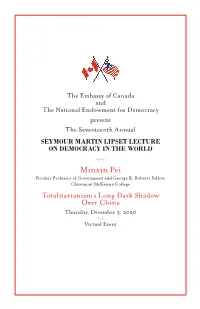

The Embassy of Canada and The National Endowment for Democracy present The Seventeenth Annual SEYMOUR MARTIN LIPSET LECTURE ON DEMOCRACY IN THE WORLD Minxin Pei Pritzker Professor of Government and George R. Roberts Fellow, Claremont McKenna College Totalitarianism’s Long Dark Shadow Over China Thursday, December 3, 2020 Virtual Event Minxin Pei Pritzker Professor of Government and George R. Roberts Fellow, Claremont McKenna College Dr. Minxin Pei is the Tom and Mar- Trapped Transition: The Limits of Develop- got Pritzker ’72 Professor of Gov- mental Autocracy (Harvard University ernment and George R. Roberts Fel- Press, 2006), and China’s Crony Capi- low at Claremont McKenna College. talism: The Dynamics of Regime Decay (Har- He is also a non-resident senior fel- vard University Press, 2016). His low of the German Marshall Fund of research has been published in For- the United States. He serves on the eign Policy, Foreign Affairs, The National In- editorial board of the Journal of Democ- terest, Modern China, China Quarterly, Jour- racy and as editor-in-chief of the Chi- nal of Democracy, and in numerous na Leadership Monitor. Prior to joining edited volumes. Claremont McKenna in 2009, Dr. Dr. Pei’s op-eds have appeared Pei was a senior associate and the di- in the Financial Times, New York Times, rector of the China Program at the Washington Post, Newsweek International, Carnegie Endowment for Interna- and other major newspapers. Dr. tional Peace. Pei received his Ph.D. in political A renowned scholar of democra- science from Harvard University. tization in developing countries, He is a recipient of numerous pres- economic reform and governance tigious fellowships, including the in China, and U.S.-China rela- National Fellowship at the Hoover tions, he is the author of From Reform Institution at Stanford University, to Revolution: The Demise of Communism in the McNamara Fellowship at the China and the Soviet Union (Harvard World Bank, and the Olin Faculty University Press, 1994), China’s Fellowship of the Olin Foundation. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar). -

Recipients of Asa Awards

APPENDIX 133 APPENDIX 11: RECIPIENTS OF ASA AWARDS MacIver Award 1956 E. Franklin Frazier, The Black Bourgeoisie (Free Press, 1957) 1957 no award given 1958 Reinhard Bendix, Work and Authority in Industry (Wiley, 1956) 1959 August B. Hollingshead and Frederick C. Redlich, Social Class and Mental Illness: A Community Study (Wiley, 1958) 1960 no award given 1961 Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Doubleday, 1959) 1962 Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics (Doubleday, 1960) 1963 Wilbert E. Moore, The Conduct of the Corporation (Random House, 1962) 1964 Shmuel N. Eisenstadt, The Political Systems of Empires (Free Press of Glencoe, 1963) 1965 William J. Goode, World Revolution and Family Patterns (Glencoe, 1963) 1966 John Porter, The Vertical Mosaic: An Analysis of Social Class and Power in Canada (University of Toronto, 1965) 1967 Kai T. Erikson, Wayward Puritans (Wiley, 1966) 1968 Barrington Moore, Jr., Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Beacon, 1966) Sorokin Award 1968 Peter M. Blau, Otis Dudley Duncan, and Andrea Tyree, The American Occupational Structure (Wiley, 1967) 1969 William A. Gamson, Power and Discontent (Dorsey, 1968) 1970 Arthur L. Stinchcombe, Constructing Social Theories (Harcourt, Brace, & World, 1968) 1971 Robert W. Friedrichs, A Sociology of Sociology; and Harrison C. White, Chains of Opportunity: Systems Models of Mobility in Organization (Free Press, 1970) 1972 Eliot Freidson, Profession of Medicine: A Study of the Sociology of Applied Knowledge (Dodd, Mead, 1970) 1973 no award given 1974 Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures (Basic, 1973); and Christopher Jencks, Inequality (Basic, 1972) 1975 Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World System (Academic Press, 1974) 1976 Jeffrey Paige, Agrarian Revolution: Social Movements and Export Agriculture in the Underdeveloped World (Free Press, 1975); and Robert Bellah, The Broken Covenant: American Civil Religion in Time of Trial (Seabury Press, 1975) 1977 Kai T. -

Demographic Destinies

DEMOGRAPHIC DESTINIES Interviews with Presidents of the Population Association of America Interview with Kingsley Davis PAA President in 1962-63 This series of interviews with Past PAA Presidents was initiated by Anders Lunde (PAA Historian, 1973 to 1982) And continued by Jean van der Tak (PAA Historian, 1982 to 1994) And then by John R. Weeks (PAA Historian, 1994 to present) With the collaboration of the following members of the PAA History Committee: David Heer (2004 to 2007), Paul Demeny (2004 to 2012), Dennis Hodgson (2004 to present), Deborah McFarlane (2004 to 2018), Karen Hardee (2010 to present), Emily Merchant (2016 to present), and Win Brown (2018 to present) 1 KINGSLEY DAVIS PAA President in 1962-63 (No. 26). Interview with Jean van der Tak in Dr. Davis's office at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, California, May 1, 1989, supplemented by corrections and additions to the original interview transcript and other materials supplied by Dr. Davis in May 1990. CAREER HIGHLIGHTS: (Sections in quotes come from "An Attempt to Clarify Moves in Early Career," Kingsley Davis, May 1990.) Kingsley Davis was born in Tuxedo, Texas in 1908 and he grew up in Texas. He received an A.B. in English in 1930 and an M.A. in philosophy in 1932 from the University of Texas, Austin. He then went to Harvard, where he received an M.A. in sociology in 1933 and the Ph.D. in sociology in 1936. He taught sociology at Smith College in 1934-36 and at Clark University in 1936-37. From 1937 to 1944, he was Chairman of the Department of Sociology at Pennsylvania State University, although he was on leave in 1940-41 and in 1942-44. -

The Critical Turn to Public Sociology1

CS 31,3_f3_313-326 5/9/05 7:00 PM Page 313 The Critical Turn to Public Sociology1 M B (University of California – Berkeley) The standpoint of the old materialism is civil society; the standpoint of the new is human society, or social humanity. The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it. – Karl Marx Revisiting “radical sociology” of the 1970s one cannot but be struck by its unrepentant academic character, both in its analytic style and its sub- stantive remoteness. It mirrored the world it sought to conquer. For all its radicalism its immediate object was the transformation of sociology not of society. Like those Young Hegelians of whom Marx and Engels spoke so contemptuously we were fighting phrases with phrases, making revolutions with words. Our theoretical obsessions came not from the lived experience or common sense of subaltern classes, but from the con- tradictions and anomalies of our abstract research programs. The audiences for our reinventions of Marxism, and our earnest diatribes against bourgeois sociology were not agents of history – workers, peasants, minorities – but a narrow body of intellectuals, largely cut off from the world they claimed to represent. The grand exception was feminism of which Catharine MacKinnon (1989: 83) wrote that it was the “first theory to emerge from those whose interests it affirms,” although it too could enter flights of abstract theorizing, even as it demanded connection with experience. 1 Thanks to Rhonda Levine, Eddie Webster, and Erik Wright for their comments on an earlier draft. This article first appeared in Levine, 2004 and is reprinted with per- mission. -

A Century of American Exceptionalism

REVIEW ESSAY A CENTURY OF AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM: A REVIEW OF SEYMOUR MARTIN LIPSET AND GARY MARKS, IT DIDN’T HAPPEN HERE: WHY SOCIALISM FAILED IN THE UNITED STATES (NEW YORK AND LONDON: W W NORTON, 2000) Michael Biggs Thesis 11, no. 68, 2002, pp. 110-21 Friedrich Engels followed the events of 1886 across the Atlantic with jubilation. American workers had flooded into the Knights of Labor; they struck en masse for the eight-hour working day on May 1; in the November elections, they voted for labor candidates, most notably Henry George in New York City. This could not, of course, compare to Germany, where the Social Democratic Party captured 10% of the vote despite legal persecution. The Anglo-Saxons—“those damned Schleswig -Holsteiners,” as Marx joked—on both sides of the Atlantic had proved an embarrassment for Marx and Engels. In theory, the most industrially developed societies represented the future of the less developed. Yet socialism remained marginal in Britain and the United States, the capitalist societies par excellence. That is why Engels greeted the rapid growth of the American labor movement in 1886 with such enthusiasm. “[I]f we in Europe do not hurry up” he wrote, “the Americans will soon outdistance us.” There was now hope for Britain, where the Trades Union Congress was dominated by labor aristocrats devoted to retaining their privileged position within the working class. Marx’s daughter Eleanor and her husband Edward Aveling, returning from a visit to the United States, concluded: “The example of the American working men will be followed before long on the European side of the Atlantic. -

By Seymour Martin Lipset

Ideas Despite the great civil-rights triumphs of the 1960s, the politics of race once again occupies center stage in American life. Yet what appears to be a conflict between blacks and whites, Seymour Mar- tin Lipset argues, is more a struggle between the American public and the nation's political elite over the true meaning of equality. by Seymour Martin Lipset o achievement of 20th-cen- Affirmative action was born in 1965 in tury American politics sur- the spirit of the first civil-rights revolution. passes the creation of an Soon thereafter it was transformed into a enduring national consen- system of racial preferences, and today af- sus on civil rights. This firmative action is rapidly polarizing the consensus was forged dur- politics of race in America. The editorial ing the past quarter century by a civil-rights and op-ed pages bristle with affirmative ac- movement that compelled Americans fi- tion polemics and analyses. In the 1990 nally to confront the wide gap between contest for the governorship of California, their treatment of blacks and the egalitar- Republican Pete Wilson focused on the ian values of their own cherished national "quota" issue in defeating Diane Feinstein. creed. In the same year, Senator Jesse Helms won In recent years, however, the leaders of reelection in North Carolina with the help the civil-rights movement have shifted the of the quota issue, and in Louisiana ex- focus from the pursuit of equal opportunity Klansman David Duke exploited it to gain a to the pursuit of substantive equality majority of white votes while losing his bid through policies of preferential treatment. -

Antonio Gramsci and His Legacy

Spring, 2001 Michael Burawoy Sociology 202B ANTONIO GRAMSCI AND HIS LEGACY What is the relation between Marxism and Sociology? Alvin Gouldner referred to them as Siamese twins, the one dependent upon the other, yet each representing its own tradition of social thought. Thus, one of sociology’s raison d’etres has been the refutation of Marxism, specifically the claim of an emancipatory life beyond capitalism. Think of the writings of Weber, Durkheim, Pareto, and Parsons all of which sought to dismiss or refute the possibility of a world freer or fairer than capitalism. From the other side, Perry Anderson has argued that following the defeat of socialism, whether by fascism or Stalinism, there emerged a distinctive “Western Marxism,” which defined itself by its critique of bourgeois thought, especially in the realm of philosophy but also of sociology. Gramsci, perhaps the greatest of Western Marxists, engaged the vision of the great Italian Hegelian philosopher Croce but he also tangled with sociology. As we will see, we may think of Gramsci as Marxism’s sociologist. Writing in the euphoric times of the early 1970s, Anderson was critical of Western Marxism for having lost its bearings. Its critical energies had become so focused on bourgeois thought that it had lost touch with the working class. Anderson proposed the renewal of an independent, Trotsky-inspired, Marxist tradition. This came to very little. Today, Marxism has once more entered a period of defeat. It cannot draw inspiration from burgeoning socialist (let alone revolutionary!) movements, but instead must rely on a hostile reengagement with bourgeois thought, not least sociology. -

Kingsley Davis 1908–1997

Kingsley Davis 1908–1997 A Biographical Memoir by Geoffrey McNicoll ©2019 National Academy of Sciences. Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. KINGSLEY DAVIS August 20, 1908–February 27, 1997 Elected to the NAS, 1966 Kingsley Davis was a significant figure in American sociology of the mid-twentieth century and by many esti- mations the leading social demographer of his generation. He made influential contributions to social stratification theory and to the study of family and kinship. He was an early theorist of demographic transition—the emergence of low-mortality, low-fertility regimes in industrializing societies—and a protagonist in major and continuing debates on policy responses to rapid population growth in low-income countries. Davis held faculty appointments at a sucession of leading universities, for longest at the University of California, Berkleley. He was honored by his peers in both sociology By Geoffrey McNicoll and demography: president of the America Sociological Association in 1959 and of the Population Association of America in 1962-’63. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1966, the first sociologist to be a member. Kingsley Davis was born in Tuxedo, Texas, a small community near Abilene, in 1908. His parents were Joseph Dyer Davis, a physician, and Winifred Kingsley Davis; he was a collateral descendant of Jefferson Davis. He took his baccalaureate from the University of Texas in 1930. (Revisiting the campus decades later as a distinguished professor, he allowed that he would not have qualified for admission under later, more stringent criteria.) Two years later at the same institution he received an MA in philosophy with a thesis on the moral philosophy of Bertrand Russell. -

American Exceptionalism : a Double Edged Sword 4/1/15, 16:59

WashingtonPost.com: American Exceptionalism : A Double Edged Sword 4/1/15, 16:59 [an error occurred while processing this directive] Go to Chapter One Section American Exceptionalism A Double Edged Sword By Seymour Martin Lipset Chapter One: Ideology, Politics, and Deviance Born out of revolution, the United States is a country organized around an ideology which includes a set of dogmas about the nature of a good society. Americanism, as different people have pointed out, is an "ism" or ideology in the same way that communism or fascism or liberalism are isms. As G. K. Chesterton put it: "America is the only nation in the world that is founded on a creed. That creed is set forth with dogmatic and even theological lucidity in the Declaration of Independence. ." As noted in the Introduction, the nation's ideology can be described in five words: liberty, egalitarianism, individualism, populism, and laissezfaire. The revolutionary ideology which became the American Creed is liberalism in its eighteenth- and nineteenth- century meanings, as distinct from conservative Toryism, statist communitarianism, mercantilism, and noblesse oblige dominant in monarchical, state-church-formed cultures. Other countries' senses of themselves are derived from a common history. Winston Churchill once gave vivid evidence to the difference between a national identity rooted in history and one defined by ideology in objecting to a proposal in 1940 to outlaw the anti-war Communist Party. In a speech in the House of Commons, Churchill said that as far as he knew, the Communist Party was composed of Englishmen and he did not fear an Englishman. -

TRANSFORMATIONS Mprntiw Study Of& Tm~Zsfmmations

TRANSFORMATIONS mprntiw study of& tm~zsfmmations CSST WORKING PAPERS The University of Michigan Ann Arbor "What We Talk About When We. Talk About History: The Conversations of History and Sociology" Terrence McDonald CSST Working CRSO Working Paper #52 Paper #44 2 October 1990 What We ~alkAbout When We Talk About ~istory: The Conversations of History and.Sociology1 Terrence J. McDonald As the epigraph for his enormously influential 1949 book Social Theorv and Social Structure Robert K. Merton selected the now well known opinion of Alfred North Whitehead that Ita science which hesitates to forget its founders is lost.tt And both history and sociology have been struggling with the implications of that statement ever since. On the one hand, it was the belief that it was possible to forget one's ttfounderswthat galvanized the social scientists (including historians) of Mertonfs generation to reinvent their disciplines. But on the other hand, it was the hubris of that view that ultimately undermined the disciplinary authority that they set out to construct, for in the end neither their propositions about epistemology or society could escape from "history."2 Social and ideological conflict in American society undermined the correspondence between theories of consensus and latent functions and the Itrealitynthey sought to explain; the belief in a single, scientific, transhistorical road to cumulative knowledge was assaulted by theories of paradigms and incommensurability; marxist theory breached the walls of both idealism and the ideology of scientific neutrality only to be overrun, in its turn, by the hordes of the ttpoststt:post-positivism, post-modernism, post-marxism, post-structuralism, and others too numerous to mention. -

On American Liberalism's Troubled Relationship with Psychology

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Honors Theses Student Research 2010 Therapeutic Discourse and the American Public Philosophy: On American Liberalism's Troubled Relationship with Psychology Clifford D. Vickrey Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses Part of the Other Philosophy Commons, Political Theory Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Vickrey, Clifford D., "Therapeutic Discourse and the American Public Philosophy: On American Liberalism's Troubled Relationship with Psychology" (2010). Honors Theses. Paper 551. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses/551 This Honors Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Therapeutic Discourse and the American Public Philosophy: On American Liberalism’s Troubled Relationship with Psychology Clifford D. Vickrey Honors Thesis Colby College, Department of Government Prof. Joseph R. Reisert, Honors Advisor Prof. Jennifer A. Yoder, Reader December 2009 Contents Preface .........................................................................................................................................