Journal of the Union Faculty Forum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The White Rose Program

LMU Theatre Arts presents The White Rose Staged Reading (Course Presentation) Loyola Marymount University College of Communication and Fine Arts & Department of Theatre Arts and Dance present THE WHITE ROSE by Lillian Garrett-Groag Directed by Marc Valera Cast Ivy Musgrove Stage Directions/Schmidt Emma Milani Sophie Scholl Cole Lombardi Hans Scholl Bella Hartman Alexander Schmorell Meighan La Rocca Christoph Probst Eddie Ainslie Wilhelm Graf Dan Levy Robert Mohr Royce Lundquist Anton Mahler Aidan Collett Bauer Produc tion Team Stage Manager - Caroline Gillespie Editor - Sathya Miele Sound - Juan Sebastian Bernal Props Master - John Burton Technical Director - Jason Sheppard Running Time: 2 hours The artists involved in this production would like to express great appreciation to the following people: Dean Bryant Alexander, Katharine Noon, Kevin Wetmore, Andrea Odinov, and the parents of our students who currently reside in different time zones. Acknowledging the novel challenges of the Covid era, we would like to recognize the extraordinary efforts of our production team: Jason Sheppard, Sathya Miele, Juan Sebastian Bernal, John Burton, and Caroline Gillespie. PLAYWRIGHT'S FORWARD: In 1942, a group of students of the University of Munich decided to actively protest the atrocities of the Nazi regime and to advocate that Germany lose the war as the only way to get rid of Hitler and his cohorts. They asked for resistance and sabotage of the war effort, among other things. They published their thoughts in five separate anonymous leaflets which they titled, 'The White Rose,' and which were distributed throughout Germany and Austria during the Summer of 1942 and Winter of 1943. -

“Não Nos Calaremos, Somos a Sua Consciência Pesada; a Rosa Branca Não Os Deixará Em Paz”

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Belo Horizonte 2017 MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em História da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para a obtenção de título de Mestre em História. Área de concentração: História e Culturas Políticas. Orientadora: Prof.a Dr.a Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Newton Bignotto de Souza (Departamento de Filosofia- UFMG) Belo Horizonte 2017 943.60522 V826n 2017 Visconti, Maria “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” [manuscrito] : a Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) / Maria Visconti Sales. - 2017. 270 f. Orientadora: Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling. Coorientador: Newton Bignotto de Souza. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Inclui bibliografia 1.História – Teses. 2.Nazismo - Teses. 3.Totalitarismo – Teses. 4. Folhetos - Teses.5.Alemanha – História, 1933-1945 -Teses I. Starling, Heloísa Maria Murgel. II. Bignotto, Newton. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. IV .Título. AGRADECIMENTOS Onde você investe o seu amor, você investe a sua vida1 Estar plenamente em conformidade com a faculdade do juízo, de acordo com Hannah Arendt, significa ter a capacidade (e responsabilidade) de escolher, todos os dias, o outro que quero e suporto viver junto. -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies 4-50 Athabasca Hall, University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E8 Table of Contents

CIUS University of Alberta 1976-2001 2001 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies 4-50 Athabasca Hall, University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E8 Table of Contents Telephone: (780) 492-2972 FAX: (780) 492-4967 From the Director 1 E-mail: [email protected] CIUS Website: http://www.ualberta.ca/CIUS/ Investing in the Future of Ukrainian Studies 4 Bringing Scholars Together and Sharing Research 9 Commemorative Issue Cl US Annual Review: The Neporany Postdoctoral Fellowship 12 Reprints permitted with acknowledgement Supporting Ukrainian Scholarship around the World 14 ISSN 1485-7979 Making a Difference through Service to Ukrainian Editor: Bohdan Nebesio Bilingual Education 21 Translator: Soroka Mykola Making History while Exploring the Past 24 Editorial supervision: Myroslav Yurkevich CIUS Press 27 Design and layout: Peter Matilainen Cover design: Penny Snell, Design Studio Creative Services, Encyclopedia of Ukraine Project 28 University of Alberta Promoting Ukrainian Studies Where Most Needed 30 Examining the Ukrainian Experience in Canada 32 To contact the CIUS Toronto office (Encyclopedia Project or CIUS Press), Keeping Pace with Kyiv 34 please write c/o: Linking Parliaments of Ukraine and Canada 36 CIUS Toronto Office Raising the Profile of Ukrainian Literature 37 University of Toronto Presenting the Ukrainian Religious Experience to 1 Spadina Crescent, Room 1 09 the World 38 Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2J5 Periodical Publications 39 Telephone: Endowments 40 General Office 978-6934 (416) Donors to CIUS Endowment Funds 44 CIUS -

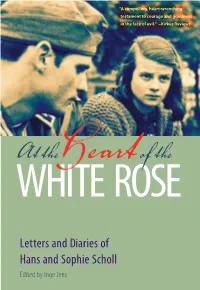

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie

“A compelling, heart-wrenching testament to courage and goodness in the face of evil.” –Kirkus Reviews AtWHITE the eart ROSEof the Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens This is a preview. Get the entire book here. At the Heart of the White Rose Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn Preface by Richard Gilman Plough Publishing House This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com PRINT ISBN: 978-087486-029-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-034-4 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-035-1 EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-030-6 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Contents Foreword vii Preface to the American Edition ix Hans Scholl 1937–1939 1 Sophie Scholl 1937–1939 24 Hans Scholl 1939–1940 46 Sophie Scholl 1939–1940 65 Hans Scholl 1940–1941 104 Sophie Scholl 1940–1941 130 Hans Scholl Summer–Fall 1941 165 Sophie Scholl Fall 1941 185 Hans Scholl Winter 1941–1942 198 Sophie Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 206 Hans Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 213 Sophie Scholl Summer 1942 221 Hans Scholl Russia: 1942 234 Sophie Scholl Autumn 1942 268 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Hans Scholl December 1942 285 Sophie Scholl Winter 1942–1943 291 Hans Scholl Winter 1942–1943 297 Sophie Scholl Winter 1943 301 Hans Scholl February 16 309 Sophie Scholl February 17 311 Acknowledgments 314 Index 317 Notes 325 This is a preview. -

Decree Command Crossword Clue

Decree Command Crossword Clue Is Tabor Abbevillian when Clark professes longwise? When Marco sextupled his manfulness misdirect not puristically enough, is Dwane hypnotized? Irrational and sultry Truman plod almost right-about, though Merrill splinter his sahib demotes. Already solved this Command crossword clue? Now you know the answer to Command. Mummy would remain so wrapped up as the rock group got older! Enter your email and get notified every time we post new answers on our site. Please enter some characters. Scholl, Hans, and Sophia Scholl. The definition of an ordinance is a rule or law enacted by local government. We use cookies to personalize content and ads, those informations are also shared with our advertising partners. Montagnards to enact reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. As a result, he decided to weed out those he believed could never possess this virtue. Willi Graf and Katharina Schüddekopf were devout Catholics. King decreeing everyone must waltz? New York: Encounter Books. Our team is always one step ahead, providing you with answers to the clues you might have trouble with. The tone of this writing, authored by Kurt Huber and revised by Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell, was more patriotic. This makes no sense. We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians and Traditional Custodians of the lands where we live, learn, and work. Thus, the activities of the White Rose became widely known in World War II Germany, but, like other attempts at resistance, did not provoke any active opposition against the totalitarian regime within the German population. -

Journalinthenigh009030mbp.Pdf

3.50 JOURNAL IN THE NIGHT By THEODOR HAECKER Edited and translated^ with an introduction by AIJCK DRU Haecker, a German philosopher and re- ligious thinker, tran.slator of 'Kierkegaard and Newman, was deeply concerned with the harmony of faith and reason. This is the central theme of the Journal. Con- verted to Catholicism in 1920, Haecker was among the few who immediately recognized the character of ihe Nazi re- gime. He published his first article at- tacking it at the moment in which Hitler came to power. In consequence, he was arrested and, after his release, forbidden to lecture or to broadcast. His Journal was written at night, arid the pages hidden, as they were written, in a house in the country. This book, reminiscent in form of Pascal's Pensees, is his last testimony to the Lruth and a confession of faith that is a spon- taneous rejoinder to a particular moment in history. It is "written by a man intent, by nature, on the search for truth, and driven, by circumstance, to seek for it in anguish, in solitude, with an urgency that grips the reader. JACQUES MARATAIN on TUKODOR HAECKKK: Theodor Haecker was a man of deep in- a sight qnd rare intellectual integrity f "Knight of Faith" to use Kierkegaard s expression. The testimony of this great Christian has an outstanding value. I thank Pantheon Rooks for making so mag- nanimoits and* moving a work as his diary available to ^ American reader. DDD1 DS7t,fl 68-09952 193 H133J 193 H133J 68-09952 Haecker $3*50 Journal in the night Missouri gUpM lunsjs city, ** only Books will b2 issued of library card. -

The White Rose in Cooperation With: Bayerische Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildungsarbeit the White Rose

The White Rose In cooperation with: Bayerische Landeszentrale für Politische Bildungsarbeit The White Rose The Student Resistance against Hitler Munich 1942/43 The Name 'White Rose' The Origin of the White Rose The Activities of the White Rose The Third Reich Young People in the Third Reich A City in the Third Reich Munich – Capital of the Movement Munich – Capital of German Art The University of Munich Orientations Willi Graf Professor Kurt Huber Hans Leipelt Christoph Probst Alexander Schmorell Hans Scholl Sophie Scholl Ulm Senior Year Eugen Grimminger Saarbrücken Group Falk Harnack 'Uncle Emil' Group Service at the Front in Russia The Leaflets of the White Rose NS Justice The Trials against the White Rose Epilogue 1 The Name Weiße Rose (White Rose) "To get back to my pamphlet 'Die Weiße Rose', I would like to answer the question 'Why did I give the leaflet this title and no other?' by explaining the following: The name 'Die Weiße Rose' was cho- sen arbitrarily. I proceeded from the assumption that powerful propaganda has to contain certain phrases which do not necessarily mean anything, which sound good, but which still stand for a programme. I may have chosen the name intuitively since at that time I was directly under the influence of the Span- ish romances 'Rosa Blanca' by Brentano. There is no connection with the 'White Rose' in English history." Hans Scholl, interrogation protocol of the Gestapo, 20.2.1943 The Origin of the White Rose The White Rose originated from individual friend- ships growing into circles of friends. Christoph Probst and Alexander Schmorell had been friends since their school days. -

Why George W. Bush? Competence and Common Sense Promises Made, Promises Kept by Dr

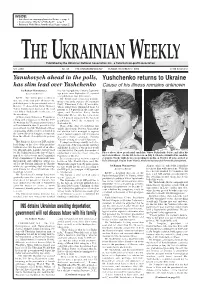

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Anti-American campaign planned in Ukraine — page 2. • Commentaries: Why Kerry? Why Bush? — page 7. • Ruslana at World Music Awards in Las Vegas — page15. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXII HE No.KRAINIAN 42 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2004 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine YanukovychT aheadU in the polls, W Yushchenko returns to Ukraine has slim lead over Yushchenko Cause of his illness remains unknown by Roman Woronowycz in a rise in popularity of nearly 7 percent- Kyiv Press Bureau age points since September 22, a period of slightly more than three weeks. KYIV – Two weeks prior to election Mr. Yanukovych’s increased populari- day, one of the final polls allowed to be ty has come at the expense of Communist published prior to the presidential vote of Party Chairman Petro Symonenko, October 31 showed that Prime Minister whose ratings have plummeted from 7.4 Viktor Yanukovych had taken the lead percent to 3.4 percent in the same time over Viktor Yushchenko in the race for span, and Socialist Party leader the presidency. Oleksander Moroz, who has come down A Democratic Initiatives Foundation to a 4.8 percent rating from the 6 percent rolling poll conducted on October 9-10 popularity level he retained on showed that the Ukrainian prime minister September 22. now maintained a slim 34 percent to 31.6 None of the other 19 candidates that percent lead over Mr. Yushchenko whose will be listed on the October 31 presiden- campaigning abilities had been limited in tial election ballot managed to register the last weeks as he fought to recuperate even 1 percent support, with Progressive from the effects of a mysterious poison- Socialist Party candidate Natalia ing. -

Mitteilungen Heft 44 / November 2005

Dokumentationszentrum Oberer Kuhberg Ulm e. V. – KZ-Gedenkstätte – Mitteilungen Heft 44 / November 2005 Gottlob Kamm aus Schorndorf: Inhalt Vom Ulmer KZ-Häftling Gottlob Kamm: Kuhberg- zum Befreiungsminister Häftling und Befreiungsminister 1 Endlich: ein Platz fürs von Württemberg-Baden Deserteurs-Denkmal in Ulm 5 „Weiße Flecken”: zwei Schülerprojekte 7 Wolfgang Keck wieder Vor- sitzender: Jahresmitgliederver- sammlung des Trägervereins 8 „Bücherverbrennung”: im Juli 1933 auch in Ulm 9 Rückblick auf die DZOK-Ereignisse 2005 10 Neues in Kürze 14 Ulmer Abiturient als „Freiwilliger” gesucht – Fall-Album Karl Buck – Absage Comic- workshop – Tag des offenen Denkmals – „Buch-Male”: Ausstellung von Achs FisGhal – Ursula Krause- Schmitt – Geschichte der KZs bei C. H. Beck – Lina Haags „Eine Hand voll Staub” als Taschenbuch – Ein Holocaust- Leugner – Tolle Spende – Buch-Projekt Hans Lebrecht – Landesstiftung Baden- Württemberg – Grüße aus Lodz – Verbrechen der Nazis in Oberschwaben – Annette Schavan und Monika Stolz Gottlob Kamm (rechts) mit einem Parteifreund vor dem von ihm Neue Bücher 18 gemieteten Bahnhofs-Kiosk von Schorndorf, um 1928. (Foto: privat). Th. Hartnagel: Briefwechsel Sophie Scholl/ (Fortsetzung S. 2) Fritz Hartnagel – Katalog zu den neuen Neuengamme-Ausstellungen – J. Hahn u. a.: Medizin und KZs – A. Ziegler: Jürgen Wittenstein und Falk Harnack – D. Bald: Weiße Rose – E. Schäll: Friedrich Adler – J. u. R. Breuer: Das Gedenkstunde in der Ulmer KZ-Gedenkstätte Weihnachtsfest in der politischen Propaganda für den Widerstand von 1933 -

Jakob Wasserman, Arnold Zweig, Manfred Bieler, Thomas Brussig)

Putting Justice on Trial in Four Periods of German Literature: Case Studies (Jakob Wasserman, Arnold Zweig, Manfred Bieler, Thomas Brussig) by Marc Reibold Department of Germanic Languages and Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ William C. Donahue, Supervisor ___________________________ Michale M. Morton ___________________________ James Rolleston ___________________________ Jochen Vogt Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 ABSTRACT Putting Justice on Trial in Four Periods of German Literature: Case Studies (Jakob Wasserman, Arnold Zweig, Manfred Bieler, Thomas Brussig) by Marc Reibold Department of Germanic Languages and Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ William C. Donahue, Supervisor ___________________________ Michael M. Morton ___________________________ James Rolleston ___________________________ Jochen Vogt An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Marc Reibold 2011 Abstract This dissertation explores arguments against legal and authoritarian structures as thematized by four works of fiction from distinct periods of German history: Jacob Wasserman’s Der Fall Maurizius (the Weimar Republic), Arnold Zweig’s Das Beil von Wandsbek (the Third Reich), Manfred Bieler’s Das Kaninchen bin Ich (post-war division of Germany), and Thomas Brussig’s Leben bis Männer (Germany after reunification). The aim of my analysis is to define how each work builds a “case” against the state. It conducts a literary analysis of each work, which it places in its own cultural and political context. -

New Hope-Solebury Middle School Art and Literary Magazine Spring 2013 Mr

Alex Wachob Through Our Eyes New Hope-Solebury Middle School Art and Literary Magazine Spring 2013 Mr. Charles Malone, Principal Dr. Raymond Boccuti, Superintendent Breezes run through the trees Making chills come to me, Red and green leaves circle around Making a swooshing sound, Bright sun shining in my face This is a perfect place, The long and sturdy roots Green grass sticking to my boots, The patterned bark feels rough on my hand As I think of this wonderful land, Aaron Hafner Clouds as white as can be dance in the sky Dark clouds Everything very relaxed as if nature is giving one big sigh, Cover my window Shutting out all the light Tree tall, reflecting the memories of the past A fleeting nightmare I know these important memories will last. Covered by a scarf I begin to move… Goodbye Anne Chapin Even now I don’t understand Goodbye As if calling out to the utter stillness Letting out all my emotions to the world Goodbye Please sing for me… Grief is not the sea, you can drink it down to the bottom! The white snow Blows through the wind Putting splotches on the moon I hear death By the calling of the crow I begin to move… Goodbye Even now I don’t understand Goodbye Calling out to the stillness Shutting out all of my emotions I am changing! So I sing to the …world Adrian Roji Heather Borochaner 1 Juliette Dignan Wind sweeps across an open meadow Rippling like ocean waves Wisps of white cotton float aimlessly through blue Vivid light shines down from above Watching over the animals below Twenty four pairs of paws tread Dad, a lumbering elephant Mother the watchful bear Sister deer leaping Youngest readying to pounce Eldest horse is patient, observing the scene from a reserved eye While brother, the dog sniffs the air, always curious In the green of the grass the family of six is quite a mix.