Journalinthenigh009030mbp.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Authenticity in Electronic Dance Music in Serbia at the Turn of the Centuries

The Other by Itself: Authenticity in electronic dance music in Serbia at the turn of the centuries Inaugural dissertation submitted to attain the academic degree of Dr phil., to Department 07 – History and Cultural Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Irina Maksimović Belgrade Mainz 2016 Supervisor: Co-supervisor: Date of oral examination: May 10th 2017 Abstract Electronic dance music (shortly EDM) in Serbia was an authentic phenomenon of popular culture whose development went hand in hand with a socio-political situation in the country during the 1990s. After the disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1991 to the moment of the official end of communism in 2000, Serbia was experiencing turbulent situations. On one hand, it was one of the most difficult periods in contemporary history of the country. On the other – it was one of the most original. In that period, EDM officially made its entrance upon the stage of popular culture and began shaping the new scene. My explanation sheds light on the fact that a specific space and a particular time allow the authenticity of transposing a certain phenomenon from one context to another. Transposition of worldwide EDM culture in local environment in Serbia resulted in scene development during the 1990s, interesting DJ tracks and live performances. The other authenticity is the concept that led me to research. This concept is mostly inspired by the book “Death of the Image” by philosopher Milorad Belančić, who says that the image today is moved to the level of new screen and digital spaces. The other authenticity offers another interpretation of a work, or an event, while the criterion by which certain phenomena, based on pre-existing material can be noted is to be different, to stand out by their specificity in a new context. -

Red Sand: Canadians in Persia & Transcaucasia, 1918 Tom

RED SAND: CANADIANS IN PERSIA & TRANSCAUCASIA, 1918 TOM SUTTON, MA THESIS ROUGH DRAFT, 20 JANUARY 2012 CONTENTS Introduction Chapter 1 Stopgap 2 Volunteers 3 The Mad Dash 4 Orphans 5 Relief 6 The Push 7 Bijar 8 Baku 9 Evacuation 10 Historiography Conclusion Introduction NOTES IN BOLD ARE EITHER TOPICS LEFT UNFINISHED OR GENERAL TOPIC/THESIS SENTENCES. REFERECNCE MAP IS ON LAST PAGE. Goals, Scope, Thesis Brief assessment of literature on Canada in the Russian Civil War. Brief assessment of literature on Canadians in Dunsterforce. 1 Stopgap: British Imperial Intentions and Policy in the Caucasus & Persia Before 1917, the Eastern Front was held almost entirely by the Russian Imperial Army. From the Baltic to the Black Sea, through the western Caucasus and south to the Persian Gulf, the Russians bolstered themselves against the Central Empires. The Russians and Turks traded Kurdistan, Assyria, and western Persia back and forth until the spring of 1917, when the British captured Baghdad, buttressing the south-eastern front. Meanwhile, the Russian army withered in unrest and desertion. Russian troops migrated north through Tabriz, Batum, Tiflis, and Baku, leaving dwindling numbers to defend an increasingly tenable front, and as the year wore on the fighting spirit of the Russian army evaporated. In the autumn of 1917, the three primary nationalities of the Caucasus – Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis – called an emergency meeting in Tiflis in reaction to the Bolshevik coup d'etat in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. In attendance were representatives from trade unions, civil employees, regional soviets, political parties, the army, and lastly Entente military agents. -

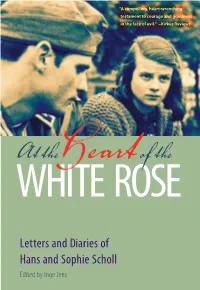

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie

“A compelling, heart-wrenching testament to courage and goodness in the face of evil.” –Kirkus Reviews AtWHITE the eart ROSEof the Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens This is a preview. Get the entire book here. At the Heart of the White Rose Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn Preface by Richard Gilman Plough Publishing House This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com PRINT ISBN: 978-087486-029-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-034-4 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-035-1 EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-030-6 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Contents Foreword vii Preface to the American Edition ix Hans Scholl 1937–1939 1 Sophie Scholl 1937–1939 24 Hans Scholl 1939–1940 46 Sophie Scholl 1939–1940 65 Hans Scholl 1940–1941 104 Sophie Scholl 1940–1941 130 Hans Scholl Summer–Fall 1941 165 Sophie Scholl Fall 1941 185 Hans Scholl Winter 1941–1942 198 Sophie Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 206 Hans Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 213 Sophie Scholl Summer 1942 221 Hans Scholl Russia: 1942 234 Sophie Scholl Autumn 1942 268 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Hans Scholl December 1942 285 Sophie Scholl Winter 1942–1943 291 Hans Scholl Winter 1942–1943 297 Sophie Scholl Winter 1943 301 Hans Scholl February 16 309 Sophie Scholl February 17 311 Acknowledgments 314 Index 317 Notes 325 This is a preview. -

The White Rose in Cooperation With: Bayerische Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildungsarbeit the White Rose

The White Rose In cooperation with: Bayerische Landeszentrale für Politische Bildungsarbeit The White Rose The Student Resistance against Hitler Munich 1942/43 The Name 'White Rose' The Origin of the White Rose The Activities of the White Rose The Third Reich Young People in the Third Reich A City in the Third Reich Munich – Capital of the Movement Munich – Capital of German Art The University of Munich Orientations Willi Graf Professor Kurt Huber Hans Leipelt Christoph Probst Alexander Schmorell Hans Scholl Sophie Scholl Ulm Senior Year Eugen Grimminger Saarbrücken Group Falk Harnack 'Uncle Emil' Group Service at the Front in Russia The Leaflets of the White Rose NS Justice The Trials against the White Rose Epilogue 1 The Name Weiße Rose (White Rose) "To get back to my pamphlet 'Die Weiße Rose', I would like to answer the question 'Why did I give the leaflet this title and no other?' by explaining the following: The name 'Die Weiße Rose' was cho- sen arbitrarily. I proceeded from the assumption that powerful propaganda has to contain certain phrases which do not necessarily mean anything, which sound good, but which still stand for a programme. I may have chosen the name intuitively since at that time I was directly under the influence of the Span- ish romances 'Rosa Blanca' by Brentano. There is no connection with the 'White Rose' in English history." Hans Scholl, interrogation protocol of the Gestapo, 20.2.1943 The Origin of the White Rose The White Rose originated from individual friend- ships growing into circles of friends. Christoph Probst and Alexander Schmorell had been friends since their school days. -

Journal of the Union Faculty Forum

Journal of the Union Faculty Forum A Publication of the Union University Faculty Forum Vol. 30 Fall 2010 Faculty Forum President’s Letter Greetings Union University Faculty! It is a great privilege to be able to serve as your Union University Faculty Forum President for the 2010-2011 academic year. I encourage you to actively participate in this organization that was created, “to provide a means for the faculty to express its interests and concerns to The Greater Faculty and the Provost, and to make recommendations about issues affecting Union University.” Last year, the membership made valuable inquiries and suggestions in matters involving facilities and equipment, student testing services, academic and University policies, technology, and fringe benefits. Your participation will ensure that faculty voices continue to be heard, and that we can provide input that supports our core values of being Excellence-Driven, Christ-Centered, People-Focused, and Future-Directed. The Faculty Forum is also pleased to provide a vehicle to share the scholarship and creative endeavors of our faculty via The Journal of the Union Faculty Forum (JUFF). Thanks to Melissa Moore and Jeannie Byrd, who served as co-editors of JUFF this year. We are also grateful to University Services and Provost Carla Sanderson who provided logistical and financial support, respectively, for JUFF. If you were not among the JUFF contributors this year, please plan now to contribute to this forum of ideas in next year’s publication. In addition to the JUFF editors, I would like to thank our other 2010-2011 Faculty Forum officers, Gavin Richardson, Vice President, and Terry Weaver, Secretary. -

Brief Descriptions of Sites Inscribed on the World Heritage List

July 2002 WHC.2002/15 Brief Descriptions of Sites Inscribed on the World Heritage List UNESCO 1972 CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE Additional copies of the Brief Descriptions, and other information concerning World Heritage, in English and French, are available from the Secretariat: UNESCO World Heritage Centre 7, place de Fontenoy 75352 Paris 07 SP France Tel: +33 (0)1 45 68 15 71 Fax: +33(0)1 45 68 55 70 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.unesco.org/whc/ http://www.unesco.org/whc/brief.htm (Brief Descriptions in English) http://www.unesco.org/whc/fr/breves.htm (Brèves descriptions en français) BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS OF THE 730 SITES INSCRIBED ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE, UNESCO, July 2002 STATE PARTY the Kbor er Roumia, the great royal mausoleum of Mauritania. Site Name Year of inscription Timgad 1982 [C: cultural; N: natural; N/C: mixed] (C ii, iii, iv) Timgad lies on the northern slopes of the Aurès mountains and was created ex nihilo as a military colony by the Emperor Trajan in A.D. 100. With its square enclosure and orthogonal design based on the cardo and decumanus, the two AFGHANISTAN perpendicular routes running through the city, it is an excellent example of Roman town planning. Minaret and Archaeological Remains of Jam 2002 (C ii, iii, iv) Kasbah of Algiers 1992 The 65m-tall Minaret of Jam is a graceful, soaring structure, dating back to the (C ii, v) 12th century. Covered in elaborate brickwork with a blue tile inscription at the The Kasbah is a unique kind of medina, or Islamic city. -

The Mosaic of Neptune and the Seasons from La Chebba Is of Interest Not Only Because of Its Fine Workmanship but Also for Its Unique Combination of Familiar Motifs

THE MOSAIC OF NEPTUNE AND THE SEASONS FRO:M LA CHEBBA THE, MOSAIC OF NEPTUNE AND THE SEASONS FR01VI LA CHEBBA by GIFTY AKO-ADOUNVO SUQmitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Gifty Ako-Adounvo, April 1991. MASTER OF ARmS McMASTER UNIVERSIT}: (Classical Studies) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Mosaic of Neptun1e and the Seasons from La Chebba. AUTHOR: Gifty Ako-Adounvo, B.A. (Hons.) (University of Ghana). SUPERVISOR: Rrofessor KM.D. Dunbabin NUMBER OF PA@ES: xiii,. 1 ~,2 11 ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the Roman mosaic of Neptune and the Seasons from La Chebba in Nortk Africa (Africa Proconsularis). The mosaic was exeavated in 1902 in a seaside', villa at La Chebba which is about 10 km. south of El Alia. The mosaic has rec~ived but brief mention in publications since the beginning of the century, in s}i>ite, of its fascinating subject matter. Chapter 1 gives a detailed description of the mosaic, which depicts in a central medallion, Neptune standing in a frontal chariot attended by two members of the marine thiasos. ]:;'our female Seasons appear iin the corner diagonals of the pa"fvement. They are flanked by seasonal animals and little scenes of seasonal activity. These seasonal vignettes and the combination of Neptune with Seasqns are unique features of this mosaic. Chapter 2 deals with the subject of the "triumph"; its modern art historical terminology, its symbolism, and the iconography of Neptune's "triumph". Some very interesting parallels appear. -

Gurevich, Mikhail. "‘

Gurevich, Mikhail. "‘. The Film Is Not About That’: Notes on (Re)Reading Tale of Tales." Global Animation Theory: International Perspectives at Animafest Zagreb. Ed. Franziska Bruckner, Nikica Gili#, Holger Lang, Daniel Šulji# and Hrvoje Turkovi#. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 143–162. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501337161.ch-009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 16:15 UTC. Copyright © Franziska Bruckner, Nikica Gili#, Holger Lang, Daniel Šulji#, Hrvoje Turkovi#, and Contributors and Cover image Zlatka Salopek 2019. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 9 ‘. The Film Is Not About That’ 1 Notes on (Re)Reading Tale of Tales Mikhail Gurevich Preface My attempts at interpretative writing on Tale of Tales have a rather long history. The fi rst lengthy essay on the fi lm I wrote around 1987; it was published, in Russian, in a preprint- type collection of articles Multiplicatsiya, Animatograph, Fantomatika under the auspices of First All-Union Animation Festival Krok–89 (held in Kiev, not yet in fl oating- on-the- ship format). In the following years, I had a chance to discuss this topic in different forms at a couple of SAS conferences. In the 1990s, Jayne Pilling tried to prepare my text for publication in her Reader in Animation Studies and even commissioned a third- party translation to assist in my then uneasy English writing; those rather laborious efforts, however, did not result in publication in the end (I was using certain wording from that translation and joint editing in subsequent work). -

Consuming Desire in Under the Skin

humanities Article Consuming Desire in Under the Skin Yael Maurer y Independent Scholar, Tel Aviv 6997801, Israel; [email protected] Formerly at The English and American Studies Department, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 6997801, Israel y (2010–2019). Received: 5 April 2020; Accepted: 29 April 2020; Published: 4 May 2020 Abstract: Jonathan Glazer’s 2013 film Under the Skin is a Gothicized science fictional narrative about sexuality, alterity and the limits of humanity. The film’s protagonist, an alien female, passing for an attractive human, seduces unwary Scottish males, leading them to a slimy, underwater/womblike confinement where their bodies dissolve and nothing but floating skins remain. In this paper, I look at the film’s engagement with the notions of consumption, the alien as devourer trope, and the nature of the ‘other’, comparing this filmic depiction with Michael Faber’s novel on which the film is based. I examine the film’s reinvention of Faber’s novel as a more open-ended allegory of the human condition as always already ‘other’. In Faber’s novel, the alien female seduces and captures the men who are consumed and devoured by an alien race, thus providing a reversal of the human species’ treatment of animals as mere food. Glazer’s film, however, chooses to remain ambiguous about the alien female’s ‘nature’ to the very end. Thus, the film remains a more open-ended meditation about alterity, the destructive potential of sexuality, and the fear of consumption which lies at the heart of the Gothic’s interrogation of porous boundaries. -

The Other Classical Body: Cupids As Mediators in Roman Visual Culture

The Other Classical Body: Cupids as Mediators in Roman Visual Culture The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitchell, Elizabeth. 2018. The Other Classical Body: Cupids as Mediators in Roman Visual Culture. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41121259 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! ! "#$!%&#$'!()*++,(*)!-%./0!(12,.+!*+!3$.,*&%'+!,4!5%3*4!6,+1*)!(1)&1'$! ! ! !"#$%%&'()($*+",'&%&+(&#" -." 7),8*-$&#!9,&(#$))"" (*" /0&":$2*'&3$4&!%;!&#$!<)*++,(+! " $+",)'($)1"2312$114&+("*2"(0&"'&53$'&4&+(%" 2*'"(0&"#&6'&&"*2" 7*8(*'"*2"90$1*%*,0." $+"(0&"%3-:&8("*2" <)*++,(*)!='(#*$%)%>/! " ;)'<)'#"=+$<&'%$(.">)4-'$#6&?"@)%%)803%&((%" =1>1+&!?@AB A"BCDE"F1$G)-&(0"@$(80&11" !11"'$60(%"'&%&'<&#H I3(0"J$&12&1#("" " " " " " F1$G)-&(0"@$(80&11" ! "#$!%&#$'!()*++,(*)!-%./0!! (12,.+!*+!3$.,*&%'+!,4!5%3*4!6,+1*)!(1)&1'$! " !"#$%&'$( ( /0&"4.'$)#"83,$#%"*2"I*4)+"<$%3)1"831(3'&"(.,$8)11.")((')8("*+&"*2"(K*" '&%,*+%&%L"&$(0&'"(0&.")'&"%&&+")%"'&,1$8)(&%"*2"(0&"6*#"*2"1*<&?"F'*%"*'"!4*'?"*'" (0&."2)#&"$+(*"(0&"-)8M6'*3+#")%"*'+)4&+()1"-*#$&%"%*"-)+)1"(0)("(0&.",'&813#&" )+."2*83%&#")((&+($*+")(")11H"/0$%"#$%%&'()($*+"*22&'%")"'&8*+%$#&')($*+"*2"(0&%&" -

Theodor Haeckers Christliches Menschenbild Im Kontext Des Kulturkatholizismus

Die „Desorientiertheit“ des Menschen – Theodor Haeckers christliches Menschenbild im Kontext des Kulturkatholizismus Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrads der Theologie der Katholisch-Theologischen Fakultät der Universität Augsburg vorgelegt von Daniela Kaschke 2019 Erstgutachter: Prof. DDr. Thomas Marschler Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Roman Siebenrock Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 7. Februar 2020 Vorwort Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde im Sommersemester 2019 von der Katholisch-Theologischen Fakultät der Universität Augsburg als Dissertationsschrift angenommen. Ich danke Herrn Prof. Dr. Dr. Thomas Marschler für die Erstellung des Erstgutachtens und die angenehme Zusam- menarbeit am Lehrstuhl für Dogmatik. Hier sei auch Frau Elke Griff gedankt, der guten Seele des Lehrstuhls. Für freundlichen Rat und die Erstellung des Zweitgutachtens danke ich Herrn Prof. Dr. Roman Siebenrock (Innsbruck). Die Hanns-Seidel-Stiftung unterstützte eine wichtige Phase dieses Projekts mit einem Stipendium, auch hierfür sei gedankt. Ideelle Förderung erfuhr ich zudem durch die Graduiertenschule für Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Augsburg. Durch die Vermittlung von Frau Prof. Dr. Kerstin Schlögl-Flierl in ihrer Funktion als Frauenbeauftragter der Fakultät kam ich in den Genuss einer durch das Büro für Chancen- gleichheit der Universität Augsburg finanzierten Hilfskraft während der Elternzeit. Frau Teresa Emanuel, die diese Aufgabe übernahm, war mir über mehrere Monate eine wertvolle Unter- stützung. Vielen Dank dafür! Ein besonderer Dank gilt den zahlreichen Unterstützer*innen aus meinem Freundes- und Kolleg*innenkreis sowie meiner Familie. Sie wissen, dass sie gemeint sind und müssen nicht namentlich genannt werden. 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis 0. Einleitung9 0.1. Forschungsstand . 10 0.2. Fragestellung und Vorgehensweise . 14 I. Die Moderne als Herausforderung für katholische Intellektuelle im be- ginnenden 20. -

Representations of Istanbul in Two Hollywood Spy Films About World War I and World War Ii

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES FILM REPRESENTATIONS OF ISTANBUL IN TWO HOLLYWOOD SPY FILMS ABOUT WORLD WAR I AND WORLD WAR II by H. ALİCAN PAMİR Thesis for the degree of Master of Philosophy October 2015 i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES FILM Thesis for the degree of Master of Philosophy REPRESENTATIONS OF ISTANBUL IN TWO HOLLYWOOD SPY FILMS ABOUT WORLD WAR I AND WORLD WAR II Hüseyin Alican Pamir This thesis focuses on the representation of Istanbul in foreign spy films. Drawing on the work of Stephen Barber (2002), Charlotte Brundson (2007), David B. Clarke (1997) and Barbara Mennel (2008), the thesis proposes five city film properties, which are used when analysing Istanbul spy films. These properties are: first, ‘city landmarks, cityscapes and city spectacles’; second, ‘cinematic constructions of social life via social and power relations’; third, the ‘relationship between the protagonist and the city’; fourth, the ‘cinematic city trope and mise-en-scène’; and finally, the ‘story of a city’ or ‘the idea of a city’.