The Mosaic of Neptune and the Seasons from La Chebba Is of Interest Not Only Because of Its Fine Workmanship but Also for Its Unique Combination of Familiar Motifs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Religions: Public Worship of the Greeks and Romans by E.M

Ancient Religions: Public worship of the Greeks and Romans By E.M. Berens, adapted by Newsela staff on 10.07.16 Word Count 1,250 Level 1190L TOP: The temple and oracle of Apollo, called the Didymaion in Didyma, an ancient Greek sanctuary on the coast of Ionia (now Turkey), Wikimedia Commons. MIDDLE: The copper statue of Zeus of Artemision in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece. BOTTOM: Engraving shows the Oracle of Delphi, bathed in shaft of light atop a pedestal and surrounded by cloaked figures, Delphi, Greece. Getty Images. Temples Long ago, the Greeks had no shrines or sanctuaries for public worship. They performed their devotions beneath the vast and boundless canopy of heaven, in the great temple of nature itself. Believing that their gods lived above in the clouds, worshippers naturally searched for the highest available points to place themselves in the closest communion possible with their gods. Therefore, the summits of high mountains were selected for devotional purposes. The inconvenience of worshipping outdoors gradually suggested the idea of building temples that would offer shelter from bad weather. These first temples were of the most simple form, without decoration. As the Greeks became a wealthy and powerful people, temples were built and adorned with great splendor and magnificence. So massively were they constructed that some of them have withstood the ravages of This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. time. The city of Athens especially contains numerous remains of these buildings of antiquity. These ruins are most valuable since they are sufficiently complete to enable archaeologists to study the plan and character of the original structures. -

Les Projets D'assainissement Inscrit S Au Plan De Développement

1 Les Projets d’assainissement inscrit au plan de développement (2016-2020) Arrêtés au 31 octobre 2020 1-LES PRINCIPAUX PROJETS EN CONTINUATION 1-1 Projet d'assainissement des petites et moyennes villes (6 villes : Mornaguia, Sers, Makther, Jerissa, Bouarada et Meknassy) : • Assainissement de la ville de Sers : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés (mise en eau le 12/08/2016); * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés. - Assainissement de la ville de Bouarada : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2016. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : les travaux sont achevés. - Assainissement de la ville de Meknassy * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2016. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés. • Makther: * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés en 2018. * Travaux complémentaires des réseaux d’assainissement : travaux en cours 85% • Jerissa: * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés et réceptionnés le 12/09/2014 ; * Réseaux d’assainissement : travaux achevés (Réception provisoire le 25/09/2017). • Mornaguia : * Station d’épuration : travaux achevés. * Réhabilitation et renforcement du réseau et transfert des eaux usées : travaux achevés Composantes du Reliquat : * Assainissement de la ville de Borj elamri : • Tranche 1 : marché résilié, un nouvel appel d’offres a été lancé, travaux en cours de démarrage. 1 • Tranche2 : les travaux de pose de conduites sont achevés, reste le génie civil de la SP Taoufik et quelques boites de branchement (problème foncier). * Acquisition de 4 centrifugeuses : Fourniture livrée et réceptionnée en date du 19/10/2018 ; * Matériel d’exploitation: Matériel livré et réceptionné ; * Renforcement et réhabilitation du réseau dans la ville de Meknassy : travaux achevés et réceptionnés le 11/02/2019. -

Latin Curse Texts: Mediterranean Tradition and Local Diversity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Acta Ant. Hung. 57, 2017, 57–82 DOI: 10.1556/068.2017.57.1.5 DANIELA URBANOVÁ LATIN CURSE TEXTS: MEDITERRANEAN TRADITION AND LOCAL DIVERSITY Summary: There are altogether about six hundred Latin curse texts, most of which are inscribed on lead tablets. The extant Latin defixiones are attested from the 2nd cent. BCE to the end of the 4th and begin- ning of the 5th century. However, the number of extant tablets is certainly not final, which is clear from the new findings in Mainz recently published by Blänsdorf (2012, 34 tablets),1 the evidence found in the fountain dedicated to Anna Perenna in Rome 2012, (26 tablets and other inscribed magical items),2 or the new findings in Pannonia (Barta 2009).3 The curse tablets were addressed exclusively to the supernatural powers, so their authors usually hid them very well to be banished from the eyes of mortals; not to speak of the randomness of the archaeological findings. Thus, it can be assumed that the preserved defixiones are only a fragment of the overall ancient production. Remarkable diversities in cursing practice can be found when comparing the preserved defixiones from particular provinces of the Roman Empire and their specific features, as this contribution wants to show. Key words: Curses with their language, formulas, and content representing a particular Mediterranean tradi- tion documented in Greek, Latin, Egyptian Coptic, as well as Oscan curse tablets, Latin curse tablets, curse tax- onomy, specific features of curse tablets from Italy, Africa, Britannia, northern provinces of the Roman Empire There are about 1600 defixiones known today from the entire ancient world dated from the 5th century BCE up to the 5th century CE, which makes a whole millennium. -

Roman Architecture Roman of Classics at Dartmouth College, Where He Roman Architecture

BLACKWELL BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO THE ANCIENT WORLD COMPANIONS TO THE ANCIENT WORLD A COMPANION TO the editors A COMPANION TO A COMPANION TO Roger B. Ulrich is Ralph Butterfield Professor roman Architecture of Classics at Dartmouth College, where he roman architecture EDITED BY Ulrich and quenemoen roman teaches Roman Archaeology and Latin and directs Dartmouth’s Rome Foreign Study roman Contributors to this volume: architecture Program in Italy. He is the author of The Roman Orator and the Sacred Stage: The Roman Templum E D I T E D B Y Roger B. Ulrich and Rostratum(1994) and Roman Woodworking James C. Anderson, jr., William Aylward, Jeffrey A. Becker, Caroline k. Quenemoen (2007). John R. Clarke, Penelope J.E. Davies, Hazel Dodge, James F.D. Frakes, Architecture Genevieve S. Gessert, Lynne C. Lancaster, Ray Laurence, A COMPANION TO Caroline K. Quenemoen is Professor in the Emanuel Mayer, Kathryn J. McDonnell, Inge Nielsen, Roman architecture is arguably the most Practice and Director of Fellowships and Caroline K. Quenemoen, Louise Revell, Ingrid D. Rowland, EDItED BY Roger b. Ulrich and enduring physical legacy of the classical world. Undergraduate Research at Rice University. John R. Senseney, Melanie Grunow Sobocinski, John W. Stamper, caroline k. quenemoen A Companion to Roman Architecture presents a She is the author of The House of Augustus and Tesse D. Stek, Rabun Taylor, Edmund V. Thomas, Roger B. Ulrich, selective overview of the critical issues and approaches that have transformed scholarly the Foundation of Empire (forthcoming) as well as Fikret K. Yegül, Mantha Zarmakoupi articles on the same subject. -

Juno Covella, Perpetual Calendar of the Fellowship of Isis By: Lawrence Durdin-Robertson All Formatting Has Been Retained from the Original

Fellowship of Isis Homepage http://www.fellowshipofisis.com Juno Covella, Perpetual Calendar of the Fellowship of Isis By: Lawrence Durdin-Robertson All formatting has been retained from the original. Goddesses appear in BOLD CAPITAL letters. The Month of April APRIL 1st Roman: CERES. (Brewer, Dict.) "April Fool Perhaps it may be a relic of the Roman 'Cerealia', held at the beginning of April". See also under April 12th. Roman: CONCORDIA, VENUS and FORTUNA; The Veneralia. (Seyffert, Dict.) "Concordia . The goddess Concordia was also invoked with Venus and Fortuna, by married women on the 1st of April". (Ovid, Fasti, IV. 133) "April 1st Duly do ye worship the goddess (i.e. -Venus), ye Latin mothers and brides, and ye, too, who wear not the fillets and long robe (Frazer: 'courtesans'). Take off the golden necklaces from the marble neck of the goddess; take off her gauds; the goddess must be washed from top to toe. Then dry her neck and restore to it her golden necklaces; now give her other flowers, now give her the fresh-blown rose. Ye, too, she herself bids bathe under the green myrtle. Learn now why ye give incense to Fortuna Virilis in the place which reeks of warm water. All women strip when they enter that place Propitiate her with suplications; beauty and fortune and good fame are in her keeping". (Plutarch, Lives, Numa) on the month of April; "the women bathe on the calends, or first day of it, with myrtle garlands on their heads." (Philocalus, Kal. Anno 345) "April 1. Veneralia Ludi. (Montfaucon, Antiq. -

Genève, Le 9 Avril 1942. Geneva, April 9Th, 1942. Renseignements Reçus

R . EL. 841. SECTION D’HYGIÈNE DU SECRÉTARIAT DE LA SOCIÉTÉ DES NATIONS HEALTH SECTION OF THE SECRETARIAT OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS RELEVE EPIDEMIOLOGIQUE HEBDOMADAIRE WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL RECORD 17me année, N° 15 — 17th Year, No. 15 Genève, le 9 avril 1942. Geneva, April 9th, 1942. COMMUNIQUÉ DE L’OFFICE INTERNATIONAL D’HYGIÈNE PUBLIQUE N ° 697 Renseignements reçus du 27 mars au 2 avril 1942. Ce Communiqué contient les informations reçues par l’Office This Communiqué incorporates information supplied to the International d'Hygiène publique en exécution de la Convention Office International d’Hygiène publique under the terms of sanitaire internationale de 1926, directement ou par l’inter the International Sanitary Convention, 1926, directly or through médiaire des Bureaux suivants, agissant comme Bureaux the folloWing organisations, Which act as regional Bureaux for régionaux pour l’application de cette Convention: the purposes of that Convention: Bureau d’Extrême-Orient de l’Organisation d'hygiène de la League of Nations, Health Organisation, Far- Eastern Société des Nations, Singapour. Bureau, Singapore. Bureau Sanitaire Panaméricain, Washington. The Pan-American Sanitary Bureau, Washington. Bureau Régional d'informations sanitaires pour le Proche- The Regional Bureau for Sanitary Information in the Orient, Alexandrie. Near East, Alexandria. Explication des signes: signifie seulement que le chiffre Explanation of signs : f merely indicates that the reported des cas et décès est supérieur à celui de la période précédente; figure of cases and deaths is higher than that for the previous \ que ce chiffre est en baisse; —► qu'il n’a pas sensiblement period; 'n* that the figure is loWer; —*■ that it has not changed varié. -

Authenticity in Electronic Dance Music in Serbia at the Turn of the Centuries

The Other by Itself: Authenticity in electronic dance music in Serbia at the turn of the centuries Inaugural dissertation submitted to attain the academic degree of Dr phil., to Department 07 – History and Cultural Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Irina Maksimović Belgrade Mainz 2016 Supervisor: Co-supervisor: Date of oral examination: May 10th 2017 Abstract Electronic dance music (shortly EDM) in Serbia was an authentic phenomenon of popular culture whose development went hand in hand with a socio-political situation in the country during the 1990s. After the disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1991 to the moment of the official end of communism in 2000, Serbia was experiencing turbulent situations. On one hand, it was one of the most difficult periods in contemporary history of the country. On the other – it was one of the most original. In that period, EDM officially made its entrance upon the stage of popular culture and began shaping the new scene. My explanation sheds light on the fact that a specific space and a particular time allow the authenticity of transposing a certain phenomenon from one context to another. Transposition of worldwide EDM culture in local environment in Serbia resulted in scene development during the 1990s, interesting DJ tracks and live performances. The other authenticity is the concept that led me to research. This concept is mostly inspired by the book “Death of the Image” by philosopher Milorad Belančić, who says that the image today is moved to the level of new screen and digital spaces. The other authenticity offers another interpretation of a work, or an event, while the criterion by which certain phenomena, based on pre-existing material can be noted is to be different, to stand out by their specificity in a new context. -

Liberalia Tu Accusas ! Restituting the Ancient Date of Caesar’S Funus*

LIBERALIA TU ACCUSAS ! RESTITUTING THE ANCIENT DATE OF CAESAR’S FUNUS* Francesco CAROTTA**, Arne EICKENBERG*** Résumé. – Du récit unanime des anciens historiographes il ressort que le funus de Jules César eut lieu le 17 mars 44 av. J.-C. Or la communauté académique moderne prétend presque aussi unanimement que cette date est erronée, sans s’accorder cependant sur une alternative. Dans la littérature scientifique on donne des dates entre le 18 et le 23, et plus précisément le 20 mars, en s’appuyant sur la chronologie avancée par Drumann et Groebe. L’analyse des sources historiques et des évènements qui suivirent l’assassinat de César jusqu’à ses funérailles, prouve que les auteurs anciens ne s’étaient pas trompés, et que Groebe avait reconnu la méprise de Drumann mais avait évité de l’amender. La correction de cette erreur invétérée va permettre de mieux examiner le contexte politique et religieux des funérailles de César. Abstract. – 17 March 44 BCE results from the reports by the ancient historiographers as to the date of Julius Caesar’s funus. However, today’s academic community has consistetly claimed that they were all mistaken, however, an alternative has not been agreed on. Dates between 18 and 23 March have been suggested in scientific literature—mostly 20 March, which is the date based on the chronology supplied by Drumann and Groebe. The analysis of the historical sources and of the events following Caesar’s murder until his funeral proves that the ancient writers were right, and that Groebe had recognized Drumann’s false dating, but avoided to adjust it. -

Antioch Mosaics and Their Mythological and Artistic Relations with Spanish Mosaics

JMR 5, 2012 43-57 Antioch Mosaics and their Mythological and Artistic Relations with Spanish Mosaics José Maria BLÁZQUEZ* – Javier CABRERO** The twenty-two myths represented in Antioch mosaics repeat themselves in those in Hispania. Six of the most fa- mous are selected: Judgment of Paris, Dionysus and Ariadne, Pegasus and the Nymphs, Aphrodite and Adonis, Meleager and Atalanta and Iphigenia in Aulis. Key words: Antioch myths, Hispania, Judgment of Paris, Dionysus and Ariadne, Pegasus and the Nymphs, Aphrodite and Adonis, Meleager and Atalanta, Iphigenia in Aulis During the Roman Empire, Hispania maintained good cultural and economic relationships with Syria, a Roman province that enjoyed high prosperity. Some data should be enough. An inscription from Málaga, lost today and therefore from an uncertain date, seems to mention two businessmen, collegia, from Syria, both from Asia, who might form an single college, probably dedicated to sea commerce. Through Cornelius Silvanus, a curator, they dedicated a gravestone to patron Tiberius Iulianus (D’Ors 1953: 395). They possibly exported salted fish to Syria, because Málaca had very big salting factories (Strabo III.4.2), which have been discovered. In Córdoba, possibly during the time of Emperor Elagabalus, there was a Syrian colony that offered a gravestone to several Syrian gods: Allath, Elagabab, Phren, Cypris, Athena, Nazaria, Yaris, Tyche of Antioch, Zeus, Kasios, Aphrodite Sozausa, Adonis, Iupiter Dolichenus. They were possible traders who did business in the capital of Bética (García y Bellido 1967: 96-105). Libanius the rhetorical (Declamatio, 32.28) praises the rubbles from Cádiz, which he often bought, as being good and cheap. -

Narcissus the Hunter in the Mosaics of Antioch

Narcissus the Hunter in the Mosaics of Antioch Elizabeth M. Molacek Among the hundreds of mosaic pavements discovered at as the capital of the Hellenistic Seleucid kingdom in 300 BCE Antioch-on-the-Orontes, a total of five represent Narcissus, and remained a thriving city until the Romans took power in the beautiful youth doomed to fall in love with his own 64 BCE. Antioch became the capital of the Roman province reflection. The predominance of this subject is not entirely of Syria; however, it was captured by the Arabs in 637 CE, surprising since it is one of the most popular subjects in bringing an end to almost a thousand years of occupation.2 Roman visual culture. In his catalogue of the mosaics of While its political history is simple to trace from the Hellenis- ancient Antioch, Doro Levi suggests that Narcissus’ frequent tic founding to the Arab sacking, Antioch’s cultural identity appearance should be attributed to his watery reflection due is less transparent. The city was part of the Roman Empire to the fact that Antioch was a “town so proud of its wealth for over five hundred years, but the inhabitants of Antioch of waters, springs, and baths.”1 The youth’s association with did not immediately consider themselves Roman, identifying water may account for his repeated appearance, but the instead with their Hellenistic heritage. As was standard in the present assessment recognizes a Narcissus that is unique to Greek East, the spoken language remained Greek even after Antioch. In art of the Latin West from the first century BCE Rome established control, and many traditions and social onwards, Narcissus has a highly standardized iconography norms were deeply rooted in the Hellenistic culture.3 Antioch that emphasizes his youthful appearance, the act of seeing was a hybrid of both eastern and western influences due to his reflection, and his fate for eternity. -

Red Sand: Canadians in Persia & Transcaucasia, 1918 Tom

RED SAND: CANADIANS IN PERSIA & TRANSCAUCASIA, 1918 TOM SUTTON, MA THESIS ROUGH DRAFT, 20 JANUARY 2012 CONTENTS Introduction Chapter 1 Stopgap 2 Volunteers 3 The Mad Dash 4 Orphans 5 Relief 6 The Push 7 Bijar 8 Baku 9 Evacuation 10 Historiography Conclusion Introduction NOTES IN BOLD ARE EITHER TOPICS LEFT UNFINISHED OR GENERAL TOPIC/THESIS SENTENCES. REFERECNCE MAP IS ON LAST PAGE. Goals, Scope, Thesis Brief assessment of literature on Canada in the Russian Civil War. Brief assessment of literature on Canadians in Dunsterforce. 1 Stopgap: British Imperial Intentions and Policy in the Caucasus & Persia Before 1917, the Eastern Front was held almost entirely by the Russian Imperial Army. From the Baltic to the Black Sea, through the western Caucasus and south to the Persian Gulf, the Russians bolstered themselves against the Central Empires. The Russians and Turks traded Kurdistan, Assyria, and western Persia back and forth until the spring of 1917, when the British captured Baghdad, buttressing the south-eastern front. Meanwhile, the Russian army withered in unrest and desertion. Russian troops migrated north through Tabriz, Batum, Tiflis, and Baku, leaving dwindling numbers to defend an increasingly tenable front, and as the year wore on the fighting spirit of the Russian army evaporated. In the autumn of 1917, the three primary nationalities of the Caucasus – Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis – called an emergency meeting in Tiflis in reaction to the Bolshevik coup d'etat in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. In attendance were representatives from trade unions, civil employees, regional soviets, political parties, the army, and lastly Entente military agents. -

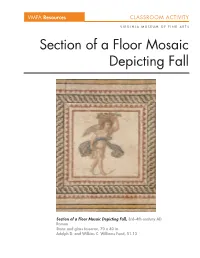

Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall

VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall, 3rd–4th century AD Roman Stone and glass tesserae, 70 x 40 in. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 51.13 VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Object Information Romans often decorated their public buildings, villas, and houses with mosaics—pictures or patterns made from small pieces of stone and glass called tesserae (tes’-er-ray). To make these mosaics, artists first created a foundation (slightly below ground level) with rocks and mortar and then poured wet cement over this mixture. Next they placed the tesserae on the cement to create a design or a picture, using different colors, materials, and sizes to achieve the effects of a painting and a more naturalistic image. Here, for instance, glass tesserae were used to add highlights and emphasize the piled-up bounty of the harvest in the basket. This mosaic panel is part of a larger continuous composition illustrating the four seasons. The seasons are personified aserotes (er-o’-tees), small boys with wings who were the mischievous companions of Eros. (Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, the Greek god and goddess of love, were known in Rome as Cupid and Venus.) Erotes were often shown in a variety of costumes; the one in this panel represents the fall season and wears a tunic with a mantle around his waist. He carries a basket of fruit on his shoulders and a pruning knife in his left hand to harvest fall fruits such as apples and grapes.