Unique Representation of a Mosaics Craftsman in a Roman Pavement from the Ancient Province Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antioch Mosaics and Their Mythological and Artistic Relations with Spanish Mosaics

JMR 5, 2012 43-57 Antioch Mosaics and their Mythological and Artistic Relations with Spanish Mosaics José Maria BLÁZQUEZ* – Javier CABRERO** The twenty-two myths represented in Antioch mosaics repeat themselves in those in Hispania. Six of the most fa- mous are selected: Judgment of Paris, Dionysus and Ariadne, Pegasus and the Nymphs, Aphrodite and Adonis, Meleager and Atalanta and Iphigenia in Aulis. Key words: Antioch myths, Hispania, Judgment of Paris, Dionysus and Ariadne, Pegasus and the Nymphs, Aphrodite and Adonis, Meleager and Atalanta, Iphigenia in Aulis During the Roman Empire, Hispania maintained good cultural and economic relationships with Syria, a Roman province that enjoyed high prosperity. Some data should be enough. An inscription from Málaga, lost today and therefore from an uncertain date, seems to mention two businessmen, collegia, from Syria, both from Asia, who might form an single college, probably dedicated to sea commerce. Through Cornelius Silvanus, a curator, they dedicated a gravestone to patron Tiberius Iulianus (D’Ors 1953: 395). They possibly exported salted fish to Syria, because Málaca had very big salting factories (Strabo III.4.2), which have been discovered. In Córdoba, possibly during the time of Emperor Elagabalus, there was a Syrian colony that offered a gravestone to several Syrian gods: Allath, Elagabab, Phren, Cypris, Athena, Nazaria, Yaris, Tyche of Antioch, Zeus, Kasios, Aphrodite Sozausa, Adonis, Iupiter Dolichenus. They were possible traders who did business in the capital of Bética (García y Bellido 1967: 96-105). Libanius the rhetorical (Declamatio, 32.28) praises the rubbles from Cádiz, which he often bought, as being good and cheap. -

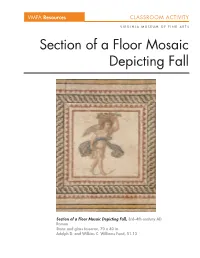

Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall

VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall, 3rd–4th century AD Roman Stone and glass tesserae, 70 x 40 in. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 51.13 VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Object Information Romans often decorated their public buildings, villas, and houses with mosaics—pictures or patterns made from small pieces of stone and glass called tesserae (tes’-er-ray). To make these mosaics, artists first created a foundation (slightly below ground level) with rocks and mortar and then poured wet cement over this mixture. Next they placed the tesserae on the cement to create a design or a picture, using different colors, materials, and sizes to achieve the effects of a painting and a more naturalistic image. Here, for instance, glass tesserae were used to add highlights and emphasize the piled-up bounty of the harvest in the basket. This mosaic panel is part of a larger continuous composition illustrating the four seasons. The seasons are personified aserotes (er-o’-tees), small boys with wings who were the mischievous companions of Eros. (Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, the Greek god and goddess of love, were known in Rome as Cupid and Venus.) Erotes were often shown in a variety of costumes; the one in this panel represents the fall season and wears a tunic with a mantle around his waist. He carries a basket of fruit on his shoulders and a pruning knife in his left hand to harvest fall fruits such as apples and grapes. -

Baring the Female Shoulder in Ancient Greece

Baring the Female Shoulder in Ancient Greece Duchess Andromeda Lykaina∗ ∗[email protected], https://andromedaofsparta.wordpress.com/ 1 1 Introduction A version of a garment in which the wearer bares one shoulder existed in Ancient Greece without doubt, but it appears to be constructed quite differently than its modern interpretations. Further, it seems to have been used sparingly and in very specific circumstances for women. We are using the broad period of Ancient Greece here as our examples are drawn from the Archaic (800 BCE - 480 BCE), Classical (480 BCE - 323 BCE), and Hellenistic (323 BCE - 146 BCE) periods. While garments differed in subtle ways across these periods, there is enough cohesion to allow us to recognize the same garment in different centuries. We will argue that the appearance of the one-shouldered chiton indicated a sharp departure from standard female behavior in proper Greek society, and we have constructed an example that closely resembles a particular instance of the garment in period. Note that the nature of the garment in most of the scenarios in which it appears lends itself to being simple and functional. Our goal in constructing an example is to show an authentic construction rather than to create a fancy garment. The rest of this work is organized as follows: x2 will present an overview of common garments in Ancient Greece so that we might put the one-shouldered chiton in context; x3 presents what evidence we have found of its appearance on women in the literary and archeological record; and x4 will present an argument as to its construction and an explanation of the example we have constructed. -

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Faya Causey With technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael R. Schilling THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES This catalogue was first published in 2012 at http: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data //museumcatalogues.getty.edu/amber. The present online version Names: Causey, Faya, author. | Maish, Jeffrey, contributor. | was migrated in 2019 to https://www.getty.edu/publications Khanjian, Herant, contributor. | Schilling, Michael (Michael Roy), /ambers; it features zoomable high-resolution photography; free contributor. | J. Paul Getty Museum, issuing body. PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads; and JPG downloads of the Title: Ancient carved ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum / Faya catalogue images. Causey ; with technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael Schilling. © 2012, 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust Description: Los Angeles : The J. Paul Getty Museum, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: “This catalogue provides a general introduction to amber in the ancient world followed by detailed catalogue entries for fifty-six Etruscan, Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Greek, and Italic carved ambers from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a The volume concludes with technical notes about scientific copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4 investigations of these objects and Baltic amber”—Provided by .0/. Figures 3, 9–17, 22–24, 28, 32, 33, 36, 38, 40, 51, and 54 are publisher. reproduced with the permission of the rights holders Identifiers: LCCN 2019016671 (print) | LCCN 2019981057 (ebook) | acknowledged in captions and are expressly excluded from the CC ISBN 9781606066348 (paperback) | ISBN 9781606066355 (epub) BY license covering the rest of this publication. -

Twinning Classics and AI

Twinning Classics and A.I.: Building the new generation of ontology-based lexicographical tools and resources for Humanists on the Semantic Web Maria Papadopoulou1,2 and Christophe Roche1,2 1 University Savoie Mont-Blanc, France 2 Liaocheng University, China [email protected] Abstract. This Twin Talk is about the ongoing collaboration between an expert in Classics and an expert in Artificial Intelligence (A.I.). Our approach set out to answer two interlinked issues, ubiquitous in the study of material culture: first, pairing things to their names (designations) and, second, having access to multi- lingual digital resources that provide information on things and their designa- tions. Our chosen domain of application was ancient Greek dress, an iconic fea- ture of ancient Greek culture offering a privileged window into the Greek belief systems and societal values. Our goal was to place the Humanist/domain expert at the centre of the endeavour enabling her to build the formal domain ontology, without requiring the assistance of an ontology engineer. The role of A.I. was to provide automations that lower the cognitive load for users unfamiliar with knowledge modelling. Building the model consisted in distinguishing between concept level (i.e. the stable domain knowledge) and term level (i.e. the terms that name the concepts in different natural languages), putting these into relation (i.e. linking the terms in different languages to their denoted concepts), and providing complete and consistent definitions for concepts (in formal -

![World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1845/world-history-part-1-teachers-guide-and-student-guide-2081845.webp)

World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [And Student Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 784 EC 308 847 AUTHOR Schaap, Eileen, Ed.; Fresen, Sue, Ed. TITLE World History--Part 1. Teacher's Guide [and Student Guide]. Parallel Alternative Strategies for Students (PASS). INSTITUTION Leon County Schools, Tallahassee, FL. Exceptibnal Student Education. SPONS AGENCY Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee. Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 841p.; Course No. 2109310. Part of the Curriculum Improvement Project funded under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B. AVAILABLE FROM Florida State Dept. of Education, Div. of Public Schools and Community Education, Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services, Turlington Bldg., Room 628, 325 West Gaines St., Tallahassee, FL 32399-0400. Tel: 850-488-1879; Fax: 850-487-2679; e-mail: cicbisca.mail.doe.state.fl.us; Web site: http://www.leon.k12.fl.us/public/pass. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF05/PC34 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Accommodations (Disabilities); *Academic Standards; Curriculum; *Disabilities; Educational Strategies; Enrichment Activities; European History; Greek Civilization; Inclusive Schools; Instructional Materials; Latin American History; Non Western Civilization; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Methods; Textbooks; Units of Study; World Affairs; *World History IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT This teacher's guide and student guide unit contains supplemental readings, activities, -

Studying the Construction of Floor Mosaics in the Roman Villa of Pisões (Portugal) Using Noninvasive Methods: High-Resolution 3D GPR and Photogrammetry

remote sensing Article Studying the Construction of Floor Mosaics in the Roman Villa of Pisões (Portugal) Using Noninvasive Methods: High-Resolution 3D GPR and Photogrammetry Bento Caldeira 1,* , Rui Jorge Oliveira 2 , Teresa Teixidó 3 , José Fernando Borges 1 , Renato Henriques 4 , André Carneiro 5 and José Antonio Peña 3 1 Institute of Earth Sciences/Physics Department, University of Évora, Rua Romão Ramalho, 59, 7002-554 Évora, Portugal 2 Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Évora, Rua Romão Ramalho, 59, 7002-554 Évora, Portugal 3 Andalusian Institute of Geophysics, University of Granada, Campus Universitario de Cartuja, 18071 Granada, Spain 4 Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal 5 Centre for Art History and Artistic Research/History and Archaeology Department, University of Évora, Largo dos Colegiais, 2, 7000-803 Évora, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 June 2019; Accepted: 9 August 2019; Published: 12 August 2019 Abstract: Over the past decade, high-resolution noninvasive sensors have been widely used in explorations of the first few meters underground at archaeological sites. However, remote sensing actions aimed at the study of structural elements that require a very high resolution are rare. In this study, layer characterization of the floor mosaic substrate of the Pisões Roman archaeological site was carried out. This work was performed with two noninvasive techniques: 3D ground penetrating radar (3D GPR) operating with a 1.6 GHz central frequency antenna, which is a very high-resolution geophysical method, and photogrammetry with imagery obtained by an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), which is a very high-resolution optical method. -

Dionysos and His Retinue in the Art of Late Roman and Byzantine Palestine

188 Renate Rosenthal-Heginbottom УДК 7.033.2...1 ББК 85.14; 6 3. 3 (0) 4 DOI:10.18688/aa155-2-18 Renate Rosenthal-Heginbottom Dionysos and His Retinue in the Art of Late Roman and Byzantine Palestine In late antique Palestine the predominant mythological subject in the visual arts was Dio- nysian imagery, reflecting a Hellenistic cultural heritage no longer identified exclusively with paganism. Yet it is not easy to understand why the vestiges of the cult of Dionysos remained omnipotent in the Near East throughout the Byzantine and early Islamic periods. The popu- larity, universality, and longevity of the god’s cult are most likely due to the convivial aspect of wine-consuming among the Greeks: the idea of sharing and enjoying [8, p. 193], [22, p. 332]. Not only did the participants of the symposium share equally in the rejoicing, but Dionysos transformed in an immaterial sense the human banquet into a divine occasion that allowed each individual to identify with the divine spirit, creating a firm bond between the human and the divine, the mortal and the immortal. Archaeological remains comprise a diversity of materials and objects and provide an in- sight into religious and profane beliefs and practices; most wide-spread and numerous are mosaic floors of reception and dining halls in private mansions. In the Holy Land Dionysian imagery is found on mosaic floors and on objects of daily use. The finds themselves seldom answer fundamental questions with regard to their secular and/or spiritual meaning and their ethno-religious association. On the material level, pagans, Jews, and Christians generally used the same objects in daily life, in funerary customs and even in ritual contexts, and embellished their homes with the same kind of mosaic floors and frescoes. -

The Mosaic of Neptune and the Seasons from La Chebba Is of Interest Not Only Because of Its Fine Workmanship but Also for Its Unique Combination of Familiar Motifs

THE MOSAIC OF NEPTUNE AND THE SEASONS FRO:M LA CHEBBA THE, MOSAIC OF NEPTUNE AND THE SEASONS FR01VI LA CHEBBA by GIFTY AKO-ADOUNVO SUQmitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Gifty Ako-Adounvo, April 1991. MASTER OF ARmS McMASTER UNIVERSIT}: (Classical Studies) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Mosaic of Neptun1e and the Seasons from La Chebba. AUTHOR: Gifty Ako-Adounvo, B.A. (Hons.) (University of Ghana). SUPERVISOR: Rrofessor KM.D. Dunbabin NUMBER OF PA@ES: xiii,. 1 ~,2 11 ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the Roman mosaic of Neptune and the Seasons from La Chebba in Nortk Africa (Africa Proconsularis). The mosaic was exeavated in 1902 in a seaside', villa at La Chebba which is about 10 km. south of El Alia. The mosaic has rec~ived but brief mention in publications since the beginning of the century, in s}i>ite, of its fascinating subject matter. Chapter 1 gives a detailed description of the mosaic, which depicts in a central medallion, Neptune standing in a frontal chariot attended by two members of the marine thiasos. ]:;'our female Seasons appear iin the corner diagonals of the pa"fvement. They are flanked by seasonal animals and little scenes of seasonal activity. These seasonal vignettes and the combination of Neptune with Seasqns are unique features of this mosaic. Chapter 2 deals with the subject of the "triumph"; its modern art historical terminology, its symbolism, and the iconography of Neptune's "triumph". Some very interesting parallels appear. -

Who Are You, Beautiful Woman? the 'Mona Lisa' from Sepphoris in The

CLARA Vol. 3, 2018 N. Sevilla-Sadeh Who Are You, Beautiful Woman? The ‘Mona Lisa’ from Sepphoris in the Light of Epicureanism and Neo-Platonism Nava Sevilla-Sadeh Abstract. The identification of the image known as the ‘Mona Lisa’ portrayed in the floor mosaic from the Roman Dionysian villa at Sepphoris has been much debated in the study of Roman mosaics. This figure has been variously identified as Aphrodite, due to the image of Eros hovering next to her; as symbolising the virtue of modesty, in relation to the apparent wine-drinking contest in the main emblem; as the ‘woman of the family of the house’, reflecting a sense of proportion, modesty, chastity, and propriety; and as the embodiment of Happiness, audaimonia, ‘the mother of all virtues’. However, due to the tendency of ancient art to generalisation, and following a new reading of the overall mosaic, the argument presented here is that this figure features within a religious and philosophical context and not a moral one, and should therefore be perceived within a broader context of Roman thought. The contention here is that the issue at stake is not the identification of this figure as a specific woman, but of the spirit that she conveys. The two main world views that seem to be embodied by this image are Epicureanism and Neo-Platonism. This argument is examined here through a discussion of Epicurean and Neo-Platonic principles and an examination of the metaphorical significance of the image of Eros as a key figure. It is compared to images in the Orpheus mosaic from Jerusalem exhibited in the Archeological Museum at Istanbul, as images that echo symbolically the main emblem. -

A Private Spectacle in Antioch: Investigation of an Initiation Scene

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation / Thesis: A PRIVATE SPECTACLE IN ANTIOCH: INVESTIGATION OF AN INITIATION SCENE Ozge Gencay, Master of Arts, 2004 Dissertation / Thesis Directed By: Professor Marjorie S. Venit Department of Art History and Archaeology The House of the Mysteries of Isis, contains a controversial mosaic pavement identified as Mors Voluntaria. It shows a female and a male figure with Hermes on their right, standing in front of a door. The subject has been identified as an initiation scene into the cult of a motherly goddess ± either Isis or Demeter--, but the lack of scenes depicting mysteries and the singularity of the iconography have also led to the suggestion of a theatrical representation. This paper aims to explain the choice of iconography from the standpoint of the ancient viewer. After a brief historical survey, each object and each figure and its gesture are investigated separately and compared with elements in contemporary works of art. These comparisons suggest a scene of the initiation into the cult of a deity with an hidden identity, which provides a secret spectacle for the pavement' s patron. A PRIVATE SPECTACLE IN ANTIOCH: INVESTIGATION OF AN INITIATION SCENE By Ozge Gencay Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2004 Advisory Committee: Professor Marjorie S. Venit, Chair Professor Marie Spiro Professor Eva Marie Stehle Acknowledgements I would like to thank to Prof. Marjorie Venit for her infinite patience and help in the preparation of this work. -

The Origin and Development of Mosaics to the Time of Augustus

THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF MOSAICS TO THE TIME OF AUGUSTUS In Memory of my Teacher Michael Avi-Yonah In the search for the origin of mosaic art, the close relationship between mosaic and inlay work cannot be ignored since both techniques are based on the same principle, i.e. the fitting together, side by side, of small pieces of one or several kinds of materials, of one or more colours. This close relationship has already been noted by Hinks: “The connexion between the mosaics proper, composed of terra cotta cones differing in colour but uniform in shape, and the inlaid work in which pieces of various shapes are fitted together, is worth recording... The columns from Al-‘Ubaid, however, seem to stand halfway between the architectural craft of terra-cotta cone-mosaic and the ornamental art of shell and lapis inlay; and to show that in Sumerian times, at all events, the two processes were closely related.”1 The art of decorating a surface by means of an inlay of coloured stones or other material, was already known in ancient Mesopotamia. The palace at Warka (Uruk, Erech) in Chaldaea, of the 4th millennium B.C.E., contains a decoration of this type. It is carried out in geometric patterns (triangles, lozenges, zigzag lines and bands),2 composed of small 1 R.P. Hinks, Catalogue of the Greek, Etruscan and Roman Paintings and Mosaics in the British Museum, (London, 1933) p. XLIV. 2 V. W.K. Loftus, Travels and Researches in Chaldaea and Susiana (New York, 1857) pp. 187ff.; G.