Post-1990 Holocaust Cinema in Israel, Germany, and Hollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert De Niro's Raging Bull

003.TAIT_20.1_TAIT 11-05-12 9:17 AM Page 20 R. COLIN TAIT ROBERT DE NIRO’S RAGING BULL: THE HISTORY OF A PERFORMANCE AND A PERFORMANCE OF HISTORY Résumé: Cet article fait une utilisation des archives de Robert De Niro, récemment acquises par le Harry Ransom Center, pour fournir une analyse théorique et histo- rique de la contribution singulière de l’acteur au film Raging Bull (Martin Scorcese, 1980). En utilisant les notes considérables de De Niro, cet article désire montrer que le travail de cheminement du comédien s’est étendu de la pré à la postproduction, ce qui est particulièrement bien démontré par la contribution significative mais non mentionnée au générique, de l’acteur au scénario. La performance de De Niro brouille les frontières des classes de l’auteur, de la « star » et du travail de collabo- ration et permet de faire un portrait plus nuancé du travail de réalisation d’un film. Cet article dresse le catalogue du processus, durant près de six ans, entrepris par le comédien pour jouer le rôle du boxeur Jacke LaMotta : De la phase d’écriture du scénario à sa victoire aux Oscars, en passant par l’entrainement d’un an à la boxe et par la prise de soixante livres. Enfin, en se fondant sur des données concrètes qui sont restées jusqu’à maintenant inaccessibles, en raison de la modestie et du désir du comédien de conserver sa vie privée, cet article apporte une nouvelle perspective pour considérer la contribution importante de De Niro à l’histoire américaine du jeu d’acteur. -

Film Reviews Jonathan Lighter

Film Reviews Jonathan Lighter Lebanon (2009) he timeless figure of the raw recruit overpowered by the shock of battle first attracted the full gaze of literary attention in Crane’s Red Badge of Courage (1894- T 95). Generations of Americans eventually came to recognize Private Henry Fleming as the key fictional image of a young American soldier: confused, unprepared, and pretty much alone. But despite Crane’s pervasive ironies and his successful refutation of genteel literary treatments of warfare, The Red Badge can nonetheless be read as endorsing battle as a ticket to manhood and self-confidence. Not so the First World War verse of Lieutenant Wilfred Owen. Owen’s antiheroic, almost revolutionary poems introduced an enduring new archetype: the young soldier as a guileless victim, meaninglessly sacrificed to the vanity of civilians and politicians. Written, though not published during the war, Owen’s “Strange Meeting,” “The Parable of the Old Man and the Young,” and “Anthem for Doomed Youth,” especially, exemplify his judgment. Owen, a decorated officer who once described himself as a “pacifist with a very seared conscience,” portrays soldiers as young, helpless, innocent, and ill- starred. On the German side, the same theme pervades novelist Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1928): Lewis Milestone’s film adaptation (1930) is often ranked among the best war movies of all time. Unlike Crane, neither Owen nor Remarque detected in warfare any redeeming value; and by the late twentieth century, general revulsion of the educated against war solicited a wide acceptance of this sympathetic image among Western War, Literature & the Arts: an international journal of the humanities / Volume 32 / 2020 civilians—incomplete and sentimental as it is. -

“Não Nos Calaremos, Somos a Sua Consciência Pesada; a Rosa Branca Não Os Deixará Em Paz”

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Belo Horizonte 2017 MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em História da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para a obtenção de título de Mestre em História. Área de concentração: História e Culturas Políticas. Orientadora: Prof.a Dr.a Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Newton Bignotto de Souza (Departamento de Filosofia- UFMG) Belo Horizonte 2017 943.60522 V826n 2017 Visconti, Maria “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” [manuscrito] : a Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) / Maria Visconti Sales. - 2017. 270 f. Orientadora: Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling. Coorientador: Newton Bignotto de Souza. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Inclui bibliografia 1.História – Teses. 2.Nazismo - Teses. 3.Totalitarismo – Teses. 4. Folhetos - Teses.5.Alemanha – História, 1933-1945 -Teses I. Starling, Heloísa Maria Murgel. II. Bignotto, Newton. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. IV .Título. AGRADECIMENTOS Onde você investe o seu amor, você investe a sua vida1 Estar plenamente em conformidade com a faculdade do juízo, de acordo com Hannah Arendt, significa ter a capacidade (e responsabilidade) de escolher, todos os dias, o outro que quero e suporto viver junto. -

Hereinspaziert! Ein Heft Übers Anfangen

Reihe 5 Hereinspaziert! Ein Heft übers Anfangen Das Magazin der Staatstheater Stuttgart Nr. 13 Staatsoper Stuttgart, Schauspiel Stuttgart, Stuttgarter Ballett Sept – Nov 2018 Sehr geehrte Leserinnen und Leser, Mitwirkende dieser Ausgabe jedem Ende wohnt ein Anfang inne! Weil wir im vorigen Heft Abschied von gleich drei Intendanten feierten, begrüßen wir nun die neuen, die mitsamt ihren Teams am Stuttgarter Ballett, an der Staatsoper Stuttgart und am Schauspiel Stuttgart starten. Ihre Arbeit haben Tamas Detrich, Viktor Schoner und Burkhard Kosminski aber schon vor Monaten, teilweise vor Jahren aufgenommen. Die Bühnenkünste sind eine Kombina tion ROMAN NOVITZKY ist ein Mehrfachbegabter: aus Marathon und Kurzstrecke. Pläne werden Jahre im Voraus Er ist Erster Solist, Cho gemacht, orientiert an der Verfügbarkeit der Künstler. Für Proben reograph – und Fotograf. Für Reihe 5 hat er zwei bleiben manchmal nur Wochen. Die Kunst besteht darin, Kolle ginnen inszeniert. Seite 30 diese unterschiedlichen Laufwege zu orchestrieren, damit alle gleichzeitig ins Ziel, also auf die Bühne, kommen. Statt jedoch nun Gebrauchsanleitungen für Dinge zu liefern, die noch weit vor uns liegen, schauen wir auf die nächsten drei Monate und entdecken dort, wen wundert es: lauter Themen für Anfänge. Im Interview erklärt Cornelius Meister, der neue General musikdirektor der Staatsoper Stuttgart, warum er mit John Cages HARALD WELZER 4' 33" einsteigt, jenem Werk, das aus nichts als Stille besteht. Der Sozialpsychologe weiß, wie Krieg entsteht und das Lernen Sie Tamas Detrich kennen, den neuen Intendanten des Morden gedeiht. Deswe gen Stuttgarter Balletts, einen wahren Meister des Beginnens. gehört die Gewalt auf die Bühne. Mit Geschichten, Der Dynamik eine perfekte Form zu geben. -

RESISTANCE MADE in HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945

1 RESISTANCE MADE IN HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945 Mercer Brady Senior Honors Thesis in History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of History Advisor: Prof. Karen Hagemann Co-Reader: Prof. Fitz Brundage Date: March 16, 2020 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. Karen Hagemann. I had not worked with Dr. Hagemann before this process; she took a chance on me by becoming my advisor. I thought that I would be unable to pursue an honors thesis. By being my advisor, she made this experience possible. Her interest and dedication to my work exceeded my expectations. My thesis greatly benefited from her input. Thank you, Dr. Hagemann, for your generosity with your time and genuine interest in this thesis and its success. Thank you to Dr. Fitz Brundage for his helpful comments and willingness to be my second reader. I would also like to thank Dr. Michelle King for her valuable suggestions and support throughout this process. I am very grateful for Dr. Hagemann and Dr. King. Thank you both for keeping me motivated and believing in my work. Thank you to my roommates, Julia Wunder, Waverly Leonard, and Jamie Antinori, for being so supportive. They understood when I could not be social and continued to be there for me. They saw more of the actual writing of this thesis than anyone else. Thank you for being great listeners and wonderful friends. Thank you also to my parents, Joe and Krista Brady, for their unwavering encouragement and trust in my judgment. I would also like to thank my sister, Mahlon Brady, for being willing to hear about subjects that are out of her sphere of interest. -

Staging the Urban Soundscape in Fiction Film

Echoes of the city : staging the urban soundscape in fiction film Citation for published version (APA): Aalbers, J. F. W. (2013). Echoes of the city : staging the urban soundscape in fiction film. Maastricht University. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20131213ja Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2013 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20131213ja Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Interpretation in Recent Literary, Film and Cultural Criticism

t- \r- 9 Anxieties of Commentary: Interpretation in Recent Literary, Film and Cultural Criticism Noel Kitg A Dissertàtion Presented to the Faculty of Arts at the University of Adelaide In Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 7994 Nwo.rà"o\ \qq5 l1 @ 7994 Noel Ki^g Atl rights reserved lr1 Abstract This thesis claims that a distinctive anxiety of commentary has entered literary, film and cultural criticism over the last thirty years/ gathering particular force in relation to debates around postmodernism and fictocriticism and those debates which are concerned to determine the most appropriate ways of discussing popular cultural texts. I argue that one now regularly encounters the figure of the hesitant, self-diiioubting cultural critic, a person who wonders whether the critical discourse about to be produced will prove either redundant (since the work will already include its own commentary) or else prove a misdescription of some kind (since the criticism will be unable to convey the essence of , say, the popular cultural object). In order to understand the emergence of this figure of the self-doubting cultural critic as one who is no longer confident that available forms of critical description are adequate and/or as one who is worried that the critical writing produced will not connect with a readership that might also have formed a constituency, the thesis proposes notions of "critical occasions," "critical assemblages," "critical postures," and "critical alibis." These are presented as a way of indicating that "interpretative occasions" are simultaneously rhetorical and ethical. They are site-specific occasions in the sense that the critic activates a rhetorical-discursive apparatus and are also site-specific in the sense that the critic is using the cultural object (book, film) as an occasion to call him or herself into question as one who requires a further work of self-stylisation (which might take the form of a practice of self-problematisation). -

Widerstand Aus Katholischen Kreisen S

Inhalt Vorwort S. 5 Einleitung S. 7 Die Künstlerkolonie am Laubenheimer Platz S. 12 Organisierter Selbstschutz gegen SA – Übergriffe in den Jahren 1931-1933 – Grossrazzia und Verhaftungswelle im «Roten Block» – Einzelschicksale in der Künstlerkolonie und die Flucht ins Exil – Zugehörigkeit zu kommunisti- schen Widerstandskreisen nach 1939 – Hilfe für Verfolgte: Helene Jacobs und Dr. Franz Kaufmann – Josi von Koskull: Eine Oppositionelle im Umfeld der Künstlerkolonie Wilmersdorfer Schulen zwischen Anpassung und Verweigerung S. 32 An der Cecilienschule (Nikolsburger Platz 5) – Das Bismarck-Lyzeum (Lassenstrasse 16-20) – Das Grunewald-Gymnasium (Herbertstrasse 2) – Die jüdische Privatschule Dr. Leonore Goldschmidt (Hohenzollerndamm 110a) – Das Heinrich-von-Kleist-Gymnasium (Kranzer Strasse 3) – Die Hindenburg-Oberrealschule (Am Volkspark 36) Jugendliche wehren sich S. 47 Bei der Bündischen Jugend – Jazz-Fans – In den Reihen der Organisation Todt Neu Beginnen S. 55 «Neu beginnen!» – George Eliasberg – Ernst Bry – Hedwig Leibetseder – Edith Jacobsohn – Edith Taglicht – Edith Schumann – Kontakte zur «Deutschen Volksfront» (Hermann Brill) Die Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei S. 63 Leitungsmitglied Walter Fabian – Käthe Schuftan – Hans Ils – Werner Jahr und Peter Loewy – Fürsorgerin Hilde Ephraim –Trotzkisten (Robert Springer) Sozialdemokraten gegen Gewalt und Diktatur S. 69 Angeklagte im Prozess 1934: Oswald Zienau und Fritz Strauss – Helene Hirscht – Jungbanner um Alfred Nau – Stummer Massenprotest – Kurt Funk – Hildegard Wegscheider – Siegfried Nestriepke – Gewerkschafter Dr. Otto Suhr – Die «Kreisauer» Carlo Mierendorff und Theodor Haubach Widerstand aus den Reihen der KPD S. 82 Illegale Gewerkschafter – Im Geheimapparat der KPD (Heinz Riegel und Erna Ueberrhein) – Hilde Rubinstein – Verborgene Druckereien und Waffen- lager – Fluchthelfer – Ruth Mock – Marta Astfalck-Vietz – Die»Rütli-Gruppe» (Hanno Günther und Elisabeth Pungs) – Schulze-Boysen/Harnack- Organisation Verfolgte Künstler S. -

In Jail Are $10 at the Door

A4 + PLUS >> Burt Reynolds dies at 82, See 2A LOCAL FOOTBALL Starbucks to Tigers take get makeover on Buchholz See Below See Page 1B WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY & SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 7 & 8, 2018 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM BOCC BACKS DOWN Friday Old-time music weekend Tax hike nixed/2A Come enjoy a weekend of music, nature and fun along the banks of the Suwannee River at the Stephen Foster CCSO Old Time Music Weekend Photog on September 7- 9 in his- toric White Springs. This three-day event offers par- gets top Weed ticipants in-depth instruc- tion in old-time music tech- niques on the banjo, guitar, nod for vocals, and fiddle for all sale levels. Evening concerts will be poster presented in the Stephen lands Foster Folk Culture Center State Park Auditorium on Friday and Saturday nights at 7 p.m. Instructors will be ‘hoe’ demonstrating their prow- ess on fiddle, banjo, guitar and vocals. Concert tickets in jail are $10 at the door. Workshops instructors will be leading workshops Self-proclaimed prostitute in fiddle, banjo, guitar, and faces sex, drug charges vocals. For more informa- in sting by sheriff’s office. tion call the Events Team at 386- 397-7005 or visit www. By STEVE WILSON floridastateparks.org/park- [email protected] events/Stephen-Foster. An 18-year-old Fort White Anti-bullying fundraiser woman is facing drug and pros- A chicken BBQ will titution charges following a take place, sponsored by mid-day sting earlier this week. Connect Church and The Sarah Williams, who was Power Team, on Friday, born in Tampa Sept. -

Program Berlinica Presents

THE AMERICAN PUBLISHING COMpaNY FOR BOOKS, MOVIES, AND MUSIC FROM BERLIN 2018 PROGRAM Berlinica Presents: 2018 Program BERLINICA, a publisher based in New from outside of Berlin, namely Mar- York and Berlin, brings Berlin to tin Luther’s Travel Guide. On the Trail of America. Our 2018 program features the Reformation in Germany, by Corne- A Place They Called Home: Reclaiming lia Doemer and Leipzig! One Thousand Citizenship, written by children and Years of German History by Sebastian grandchildren of Holocaust survi- Ringel. Both books are full color with vors who recently became German numerous pictures and maps. citizens. The collection is compiled In 2019, we will release Kurt Tuchol- and edited by Donna Swarthout. sky. The Short Fat Berliner Who Tried to Later in 2018 will have another Stop a Catastrophe With A Typewriter. book out by Kurt Tucholsky, Hereaf- This is a reprint of Harold Poor’s ter, where the iconic Weimar author landmark Tucholsky biography. Also imagines funny musing about the af- coming up: Our West-Berlin, a story terlife. The book is translated by Cin- collection by numerous Berlin writ- dy Opitz, the preface is by William ers and journalists. And finally, we Grimes. This will be our fifth book will publish a series of plays, start- by the German-Jewish writer after ing with Hinkemann by Ernst Toller, Germany? Germany! Satirical Writings; translated by Peter Wortsman. Prayer After the Slaughter, Rheinsberg; A All our books are in English and Storybook for Lovers; and Berlin! Berlin! available through Amazon, Barnes Berlinica publishes books on the & Noble, and all bookstores, and Berlin Wall and World War II history, also as ebooks. -

The Informed Victorian Reader by Christie A. P. Allen a Dissertation

The Informed Victorian Reader by Christie A. P. Allen A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Daniel S. Hack, Chair Professor Lucy Hartley Professor Adela N. Pinch Associate Professor Megan L. Sweeney Acknowledgements I would like to thank my excellent committee for the help and support they provided me in imagining, researching, and writing this dissertation. First and foremost, I’m grateful to my chair, Daniel Hack, for patiently reading and rereading my work over many years and for offering unfailingly helpful feedback. I have benefitted immeasurably from Danny’s expertise, as well as his ability to see the potential in my ideas and to push me to refine my arguments. I would also like to thank my readers, Adela Pinch, Lucy Hartley, and Megan Sweeney. Adela’s practical advice and optimism about my project have sustained me through the long process of writing a dissertation. I am grateful to Lucy for always challenging me to consider all sides of a question and to take my analysis a step further. I appreciate Meg’s thoughtful feedback on my chapters, and I will always be thankful to her for being a kind, conscientious, and resourceful mentor to me in my growth as a teacher as well as a writer. I appreciate the many other readers who have helped make this project possible. Kathryne Bevilacqua, Julia Hansen, and Logan Scherer offered feedback and moral support in the very early stages of dissertation-writing. -

Newsletter 08/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

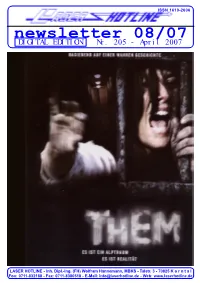

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 08/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 205 - April 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 08/07 (Nr. 205) April 2007 editorial Gefühlvoll, aber nie kitschig: Susanne Biers Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, da wieder ganz schön viel zusammen- Familiendrama über Lügen und Geheimnisse, liebe Filmfreunde! gekommen. An Nachschub für Ihr schmerzhafte Enthüllungen und tiefgreifenden Kaum ist Ostern vorbei, überraschen Entscheidungen ist ein Meisterwerk an Heimkino fehlt es also ganz bestimmt Inszenierung und Darstellung. wir Sie mit einer weiteren Ausgabe nicht. Unsere ganz persönlichen Favo- unseres Newsletters. Eigentlich woll- riten bei den deutschen Veröffentli- Schon lange hat sich der dänische Film von ten wir unseren Bradford-Bericht in chungen: THEM (offensichtlich jetzt Übervater Lars von Trier und „Dogma“ genau dieser Ausgabe präsentieren, emanzipiert, seine Nachfolger probieren andere doch im korrekten 1:2.35-Bildformat) Wege, ohne das Gelernte über Bord zu werfen. doch das Bilderbuchwetter zu Ostern und BUBBA HO-TEP. Zwei Titel, die Geblieben ist vor allem die Stärke des hat uns einen Strich durch die Rech- in keiner Sammlung fehlen sollten und Geschichtenerzählens, der Blick hinter die nung gemacht. Und wir haben es ge- bestimmt ein interessantes Double- Fassade, die Lust an der Brüchigkeit von nossen! Gerne haben wir die Tastatur Beziehungen. Denn nichts scheint den Dänen Feature für Ihren nächsten Heimkino- verdächtiger als Harmonie und Glück oder eine gegen Rucksack und Wanderschuhe abend abgeben würden.