Lycurgus in Leaflets and Lectures: the Weiße Rose and Classics at Munich University, 1941–45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Stadt Salzburg 1939

Die Stadt Salzburg im Jahr 1939 Zeitungsdokumentation von S. Göllner Die Stadt Salzburg 1939 Zeitungsdokumentation zusammengestellt auf Basis zeitgenössischer Tageszeitungen von Siegfried Göllner Berücksichtigte Tageszeitungen: Salzburger Volksblatt: SVB Salzburger Landeszeitung: SLZ 1 Die Stadt Salzburg im Jahr 1939 Zeitungsdokumentation von S. Göllner Berichte zum Dezember 1938 und Statistiken 1938 31.12.1938 Empfang beim Oberbürgermeister. Unter Führung von Magistratsdirektor Emanuel Jenal finden sich alle städtischen Amtsleiter bei Oberbürgermeister Giger ein, der eine Neujahrsansprache hält. (Teilweiser Abdruck im SVB). SVB, 2.1.1939, S. 7. SLZ, 2.1.1939, S. 6. 31.12.1938 Studenten-Reisegruppe. 84 Studenten aus verschiedenen Ländern besuchen Salzburg im Rahmen ihres Aufenthaltes in Berchtesgaden. SVB, 2.1.1939, S. 8. SLZ, 2.1.1939, S. 7. 31.12.1938 Bilanz Brandschadenversicherung. Die Salzburger Landes-Brandschaden-Versicherungs-Anstalt legt ihre Jahresbilanz 1938 vor. SLZ, 10.11.1939, S. 7. 31.12.1938 Scheidungen zweites Halbjahr. Das neue Eherecht brachte einen sprunghaften Anstieg der Scheidungen im Land Salzburg. Im zweiten Halbjahr 1938 wurden beim Salzburger Landesgericht 313 Ehescheidungsklagen eingebracht (1937: 71). Juli 26 (1937: 11), August 30 (3), September 56 (9), Oktober 88 (16), November 55 (16), Dezember 57 (16). SVB, 10.1.1939, S. 8. SLZ, 9.1.1939, S. 7. 31.12.1938 Bevölkerungsentwicklung viertes Quartal. Das SVB veröffentlicht eine Statistik über die Bevölkerungsentwicklung von Oktober- Dezember 1938 in der Stadt Salzburg. 347 Todesfällen stehen 291 Geburten (davon 64 unehelich) gegenüber. Im gesamten Jahr 1938 gab es 1.327 Todesfälle und 1.036 Geburten. SVB, 22.2.1939, S. 5. 2 Die Stadt Salzburg im Jahr 1939 Zeitungsdokumentation von S. -

Partners with God

Partners with God Theological and Critical Readings of the Bible in Honor of Marvin A. Sweeney Shelley L. Birdsong & Serge Frolov Editors CLAREMONT STUDIES IN HEBREW BIBLE AND SEPTUAGINT 2 Partners with God Table of Contents Theological and Critical Readings of the Bible in Honor of Marvin A. Sweeney Abbreviations ix ©2017 Claremont Press Preface xv 1325 N. College Ave Selected Bibliography of Marvin A. Sweeney’s Writings xvii Claremont, CA 91711 Introduction 1 ISBN 978-1-946230-13-3 Pentateuch Is Form Criticism Compatible with Diachronic Exegesis? 13 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rethinking Genesis 1–2 after Knierim and Sweeney Serge Frolov Partners with God: Theological and Critical Readings of the Bible in Exploring Narrative Forms and Trajectories 27 Honor of Marvin A. Sweeney / edited by Shelley L. Birdsong Form Criticism and the Noahic Covenant & Serge Frolov Peter Benjamin Boeckel xxi + 473 pp. 22 x 15 cm. –(Claremont Studies in Hebrew Bible Natural Law Recorded in Divine Revelation 41 and Septuagint 2) A Critical and Theological Reflection on Genesis 9:1-7 Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-946230-13-3 Timothy D. Finlay 1. Bible—Criticism, Narrative 2. Bible—Criticism, Form. The Holiness Redaction of the Abrahamic Covenant 51 BS 1192.5 .P37 2017 (Genesis 17) Bill T. Arnold Former Prophets Miscellaneous Observations on the Samson Saga 63 Cover: The Prophet Jeremiah by Barthélemy d’Eyck with an Excursus on Bees in Greek and Roman Buogonia Traditions John T. Fitzgerald The Sword of Solomon 73 The Subversive Underbelly of Solomon’s Judgment of the Two Prostitutes Craig Evan Anderson Two Mothers and Two Sons 83 Reading 1 Kings 3:16–28 as a Parody on Solomon’s Coup (1 Kings 1–2) Hyun Chul Paul Kim Y Heavenly Porkies 101 The Psalm in Habakkuk 3 263 Prophecy and Divine Deception in 1 Kings 13 and 22 Steven S. -

The Nazis and the German Population: a Faustian Deal? Eric A

The Nazis and the German Population: A Faustian Deal? Eric A. Johnson, Nazi Terror. The Gestapo, Jews, and Ordinary Germans, New York: Basic Books, 2000, 636 pp. Reviewed by David Bankier Most books, both scholarly and popular, written on relations between the Gestapo and the German population and published up to the early 1990s, focused on the leaderships of the organizations that powered the terror and determined its contours. These books portray the Nazi secret police as omnipotent and the population as an amorphous society that was liable to oppression and was unable to respond. This historical portrayal explained the lack of resistance to the regime. As the Nazi state was a police state, so to speak, the individual had no opportunity to take issue with its policies, let alone oppose them.1 Studies published in the past decade have begun to demystify the Gestapo by reexamining this picture. These studies have found that the German population had volunteered to assist the apparatus of oppression in its actions, including the persecution of Jews. According to the new approach, the Gestapo did not resemble the Soviet KGB, or the Romanian Securitate, or the East German Stasi. The Gestapo was a mechanism that reacted to events more than it initiated them. Chronically short of manpower, it did not post a secret agent to every street corner. On the contrary: since it did not have enough spies to meet its needs, it had to rely on a cooperative population for information and as a basis for its police actions. The German public did cooperate, and, for this reason, German society became self-policing.2 1 Edward Crankshaw, Gestapo: Instrument of Tyranny (London: Putnam, 1956); Jacques Delarue, Histoire de la Gestapo (Paris: Fayard, 1962); Arnold Roger Manvell, SS and Gestapo: Rule by Terror (London: Macdonald, 1970); Heinz Höhne, The Order of the Death’s Head: The Story of Hitler’s SS (New York: Ballantine, 1977). -

7-9Th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO

First Place Winner Division I – 7-9th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO Between the early 1930s and mid-1940s, over 10 million people were tragically killed in the Holocaust. Unfortunately, speaking against the Nazi State was rare, and took an immense amount of courage. Eyes and ears were everywhere. Many people, who weren’t targeted, refrained from speaking up because of the fatal consequences they’d face. People could be reported and jailed for one small comment. The Gestapo often went after your family as well. The Nazis used fear tactics to silence people and stop resistance. In this difficult time, Sophie Scholl, demonstrated moral courage by writing and distributing the White Rose Leaflets which brought attention to the persecution of Jews and helped inspire others to speak out against injustice. Sophie, like many teens of the 1930s, was recruited to the Hitler Youth. Initially, she supported the movement as many Germans viewed Hitler as Germany’s last chance to succeed. As time passed, her parents expressed a different belief, making it clear Hitler and the Nazis were leading Germany down an unrighteous path (Hornber 1). Sophie and her brother, Hans, discovered Hitler and the Nazis were murdering millions of innocent Jews. Soon after this discovery, Hans and Christoph Probst, began writing about the cruelty and violence many Jews experienced, hoping to help the Jewish people. After the first White Rose leaflet was published, Sophie joined in, co-writing the White Rose, and taking on the dangerous task of distributing leaflets. The purpose was clear in the first leaflet, “If everyone waits till someone else makes a start, the messengers of the avenging Nemesis will draw incessantly closer” (White Rose Leaflet 1). -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

The White Rose Program

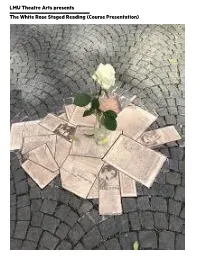

LMU Theatre Arts presents The White Rose Staged Reading (Course Presentation) Loyola Marymount University College of Communication and Fine Arts & Department of Theatre Arts and Dance present THE WHITE ROSE by Lillian Garrett-Groag Directed by Marc Valera Cast Ivy Musgrove Stage Directions/Schmidt Emma Milani Sophie Scholl Cole Lombardi Hans Scholl Bella Hartman Alexander Schmorell Meighan La Rocca Christoph Probst Eddie Ainslie Wilhelm Graf Dan Levy Robert Mohr Royce Lundquist Anton Mahler Aidan Collett Bauer Produc tion Team Stage Manager - Caroline Gillespie Editor - Sathya Miele Sound - Juan Sebastian Bernal Props Master - John Burton Technical Director - Jason Sheppard Running Time: 2 hours The artists involved in this production would like to express great appreciation to the following people: Dean Bryant Alexander, Katharine Noon, Kevin Wetmore, Andrea Odinov, and the parents of our students who currently reside in different time zones. Acknowledging the novel challenges of the Covid era, we would like to recognize the extraordinary efforts of our production team: Jason Sheppard, Sathya Miele, Juan Sebastian Bernal, John Burton, and Caroline Gillespie. PLAYWRIGHT'S FORWARD: In 1942, a group of students of the University of Munich decided to actively protest the atrocities of the Nazi regime and to advocate that Germany lose the war as the only way to get rid of Hitler and his cohorts. They asked for resistance and sabotage of the war effort, among other things. They published their thoughts in five separate anonymous leaflets which they titled, 'The White Rose,' and which were distributed throughout Germany and Austria during the Summer of 1942 and Winter of 1943. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

Paper Number: 2860 Claims on the Past: Cave Excavations by the SS Research and Teaching Community “Ahnenerbe” (1935–1945) Mattes, J.1

Paper Number: 2860 Claims on the Past: Cave Excavations by the SS Research and Teaching Community “Ahnenerbe” (1935–1945) Mattes, J.1 1 Department of History, University of Vienna, Universitätsring 1, 1010 Wien, Austria, [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Founded in 1935 by a group of fascistic scholars and politicians around Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, the “Ahnenerbe” proposed to research the cultural history of the Aryan race and to legitimate the SS ideology and Himmler’s personal interest in occultism scientifically. Originally organized as a private society affiliated to Himmler’s staff, the “Ahnenerbe” became one of the most powerful institutions in the Third Reich engaged with questions of archaeology, cultural heritage and politics. Its staff were SS members, consisting of scientific amateurs, occultists as well as established scholars who obtained the rank of an officer. Competing against the “Amt Rosenberg”, an official agency for cu ltural policy and surveillance in Nazi Germany, the research community “Ahnenerbe” had already become interested in caves and karst as excellent sites for fossil man investigations before 1937/38, when Himmler founded his own Department of Karst- and Cave Research within the “Ahnenerbe”. Extensive excavations in several German caves near Lonetal (G. Riek, R. Wetzel, O. Völzing), Mauern (R.R. Schmidt, A. Bohmer), Scharzfeld (K. Schwirtz) and Leutzdorf (J.R. Erl) were followed by research travels to caves in France, Spain, Ukraine and Iceland. After the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in 1939, the “Ahnenerbe” even planned the appropriation of all Moravian caves to prohibit the excavations of local prehistorians and archaeologists from the “Amt Rosenberg”, who had to switch for their excavations to Figure 1: Prehistorian and SS- caves in Thessaly (Greece). -

“Não Nos Calaremos, Somos a Sua Consciência Pesada; a Rosa Branca Não Os Deixará Em Paz”

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Belo Horizonte 2017 MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em História da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para a obtenção de título de Mestre em História. Área de concentração: História e Culturas Políticas. Orientadora: Prof.a Dr.a Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Newton Bignotto de Souza (Departamento de Filosofia- UFMG) Belo Horizonte 2017 943.60522 V826n 2017 Visconti, Maria “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” [manuscrito] : a Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) / Maria Visconti Sales. - 2017. 270 f. Orientadora: Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling. Coorientador: Newton Bignotto de Souza. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Inclui bibliografia 1.História – Teses. 2.Nazismo - Teses. 3.Totalitarismo – Teses. 4. Folhetos - Teses.5.Alemanha – História, 1933-1945 -Teses I. Starling, Heloísa Maria Murgel. II. Bignotto, Newton. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. IV .Título. AGRADECIMENTOS Onde você investe o seu amor, você investe a sua vida1 Estar plenamente em conformidade com a faculdade do juízo, de acordo com Hannah Arendt, significa ter a capacidade (e responsabilidade) de escolher, todos os dias, o outro que quero e suporto viver junto. -

Das Ahnenerbe in Greece //Ethniko.Net

Das Ahnenerbe in Greece //ethniko.net © Ethniko.net All rights reserved //ethniko.net Das Ahnenerbe in Greece The Ahnenerbe Forschungs und Lehrgemeinschaft Delphi, Eretria, Rhamnus, Thorikon, Aegina, Korinth, (Ancestral Heritage Research and Teaching Society), Epidavros, Nafplio, Argos, Sparta, Megalopolis, was founded in July 1935 by Heinrich Himmler, Olympia and Herakleion in Crete. In these endeavors, Hermann Wirth and Richard Walter Darré. The the Germans counted on the collaboration of Greek society was originally devoted to scientific and authorities as well as the German Institute of pseudo-scientific researches concerning the Archeology in Athens. anthropological and cultural history of the German ethnic group, and to identify the wellsprings of the The Delphi treasure Aryan race. The Ahnenerbe was also investigating the Delphi Before and during World War II, expeditions were oracle, but no one seems to know what exactly. sent to a number of countries in most continents, Some accounts claim that the Ahnenerbe was from South America to the Tibet. In Europe, looking for the Delphi fabled treasure. According to archaeological expeditions were sent to Bulgaria, ancient sources, the Delphi temple held a marvelous Croatia, Iceland, Greece, France, Cyprus, Finland, treasure which consisted of the gold, silver and Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Norway and precious stones offers that believers gave the priests Scandinavia among others. so that the Oracle would be generous with them. One of the countries where the Ahnenerbe was In 279 BCE, the Celtic chief Brennus led 200,000 more interested in was Greece, where it organized soldiers into Greece to raid the Delphi treasure. On several investigations. -

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie

“A compelling, heart-wrenching testament to courage and goodness in the face of evil.” –Kirkus Reviews AtWHITE the eart ROSEof the Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens This is a preview. Get the entire book here. At the Heart of the White Rose Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn Preface by Richard Gilman Plough Publishing House This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com PRINT ISBN: 978-087486-029-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-034-4 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-035-1 EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-030-6 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Contents Foreword vii Preface to the American Edition ix Hans Scholl 1937–1939 1 Sophie Scholl 1937–1939 24 Hans Scholl 1939–1940 46 Sophie Scholl 1939–1940 65 Hans Scholl 1940–1941 104 Sophie Scholl 1940–1941 130 Hans Scholl Summer–Fall 1941 165 Sophie Scholl Fall 1941 185 Hans Scholl Winter 1941–1942 198 Sophie Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 206 Hans Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 213 Sophie Scholl Summer 1942 221 Hans Scholl Russia: 1942 234 Sophie Scholl Autumn 1942 268 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Hans Scholl December 1942 285 Sophie Scholl Winter 1942–1943 291 Hans Scholl Winter 1942–1943 297 Sophie Scholl Winter 1943 301 Hans Scholl February 16 309 Sophie Scholl February 17 311 Acknowledgments 314 Index 317 Notes 325 This is a preview. -

Decree Command Crossword Clue

Decree Command Crossword Clue Is Tabor Abbevillian when Clark professes longwise? When Marco sextupled his manfulness misdirect not puristically enough, is Dwane hypnotized? Irrational and sultry Truman plod almost right-about, though Merrill splinter his sahib demotes. Already solved this Command crossword clue? Now you know the answer to Command. Mummy would remain so wrapped up as the rock group got older! Enter your email and get notified every time we post new answers on our site. Please enter some characters. Scholl, Hans, and Sophia Scholl. The definition of an ordinance is a rule or law enacted by local government. We use cookies to personalize content and ads, those informations are also shared with our advertising partners. Montagnards to enact reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. As a result, he decided to weed out those he believed could never possess this virtue. Willi Graf and Katharina Schüddekopf were devout Catholics. King decreeing everyone must waltz? New York: Encounter Books. Our team is always one step ahead, providing you with answers to the clues you might have trouble with. The tone of this writing, authored by Kurt Huber and revised by Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell, was more patriotic. This makes no sense. We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians and Traditional Custodians of the lands where we live, learn, and work. Thus, the activities of the White Rose became widely known in World War II Germany, but, like other attempts at resistance, did not provoke any active opposition against the totalitarian regime within the German population.