An Analysis on the Influence of Christianity on the White Rose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7-9Th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO

First Place Winner Division I – 7-9th Grades Waves of Resistance by Chloe A. Girls Athletic Leadership School, Denver, CO Between the early 1930s and mid-1940s, over 10 million people were tragically killed in the Holocaust. Unfortunately, speaking against the Nazi State was rare, and took an immense amount of courage. Eyes and ears were everywhere. Many people, who weren’t targeted, refrained from speaking up because of the fatal consequences they’d face. People could be reported and jailed for one small comment. The Gestapo often went after your family as well. The Nazis used fear tactics to silence people and stop resistance. In this difficult time, Sophie Scholl, demonstrated moral courage by writing and distributing the White Rose Leaflets which brought attention to the persecution of Jews and helped inspire others to speak out against injustice. Sophie, like many teens of the 1930s, was recruited to the Hitler Youth. Initially, she supported the movement as many Germans viewed Hitler as Germany’s last chance to succeed. As time passed, her parents expressed a different belief, making it clear Hitler and the Nazis were leading Germany down an unrighteous path (Hornber 1). Sophie and her brother, Hans, discovered Hitler and the Nazis were murdering millions of innocent Jews. Soon after this discovery, Hans and Christoph Probst, began writing about the cruelty and violence many Jews experienced, hoping to help the Jewish people. After the first White Rose leaflet was published, Sophie joined in, co-writing the White Rose, and taking on the dangerous task of distributing leaflets. The purpose was clear in the first leaflet, “If everyone waits till someone else makes a start, the messengers of the avenging Nemesis will draw incessantly closer” (White Rose Leaflet 1). -

“Não Nos Calaremos, Somos a Sua Consciência Pesada; a Rosa Branca Não Os Deixará Em Paz”

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Belo Horizonte 2017 MARIA VISCONTI SALES “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” A Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação em História da Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requisito parcial para a obtenção de título de Mestre em História. Área de concentração: História e Culturas Políticas. Orientadora: Prof.a Dr.a Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Newton Bignotto de Souza (Departamento de Filosofia- UFMG) Belo Horizonte 2017 943.60522 V826n 2017 Visconti, Maria “Não nos calaremos, somos a sua consciência pesada; a Rosa Branca não os deixará em paz” [manuscrito] : a Rosa Branca e sua resistência ao nazismo (1942-1943) / Maria Visconti Sales. - 2017. 270 f. Orientadora: Heloísa Maria Murgel Starling. Coorientador: Newton Bignotto de Souza. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. Inclui bibliografia 1.História – Teses. 2.Nazismo - Teses. 3.Totalitarismo – Teses. 4. Folhetos - Teses.5.Alemanha – História, 1933-1945 -Teses I. Starling, Heloísa Maria Murgel. II. Bignotto, Newton. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. IV .Título. AGRADECIMENTOS Onde você investe o seu amor, você investe a sua vida1 Estar plenamente em conformidade com a faculdade do juízo, de acordo com Hannah Arendt, significa ter a capacidade (e responsabilidade) de escolher, todos os dias, o outro que quero e suporto viver junto. -

The Sophia Sun Newsletter of the Anthroposophical Society in North Carolina

The Sophia Sun Newsletter of the Anthroposophical Society in North Carolina June 2008 Volume I, Number 3 In This Issue: Calendar…………………3 - 4 Study Groups…….…………5 Rev. Dancey Visit……….18 St. John’s …………………...6 K. Morse Visit……..……..18 Archangel Uriel….…………7 News From China….…….20 Branch Meeting…………….8 African Aid………………...23 Conference Review………..9 On Media and Youth……..26 Poem by Eve Olive………..13 Anthroposophy’s White Natalie Tributes…..…….…15 Rose…………………………28 2 From the Editor: I would like to close this letter with a verse, Dear Friends: which was spoken at the John The theme of this June issue of The Sophia Alexandra Conference, which exemplifies Sun is very much aligned with the Mission the Urielic Spirit: of Uriel, the Archangel of Summer, who So long as Thou dost feel the pain admonishes us to awaken our conscience Which I am spared, and to shine the Light of Truth on all things. The Christ unrecognized We begin with our Festival of St. John, Is working in the World. whose guiding spirit was Uriel and whose For weak is still the Spirit personality and Mission John epitomized in While each is only capable of his incarnations as Elijah and as John. suffering Next is an article about the conference Through his own body. “From the Ashes of 9/11: Called to a New Rudolf Steiner Birth of Freedom”. The conference focused on an incident that should have been a The Sophia Sun will be on hiatus during Urielic awakening to conscience and for the summer months. In the meantime, have a many it was, but for our government, it restful summer. -

Sophie Scholl: the Final Days 120 Minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany)

Friday 26th June 2015 - ĊAK, Birkirkara Sophie Scholl: The Final Days 120 minutes – Biography/Drama/Crime – 24 February 2005 (Germany) A dramatization of the final days of Sophie Scholl, one of the most famous members of the German World War II anti-Nazi resistance movement, The White Rose. Director: Marc Rothemund Writer: Fred Breinersdorfer. Music by: Reinhold Heil & Johnny Klimek Cast: Julia Jentsch ... Sophie Magdalena Scholl Alexander Held ... Robert Mohr Fabian Hinrichs ... Hans Scholl Johanna Gastdorf ... Else Gebel André Hennicke ... Richter Dr. Roland Freisler Anne Clausen ... Traute Lafrenz (voice) Florian Stetter ... Christoph Probst Maximilian Brückner ... Willi Graf Johannes Suhm ... Alexander Schmorell Lilli Jung ... Gisela Schertling Klaus Händl ... Lohner Petra Kelling ... Magdalena Scholl The story The Final Days is the true story of Germany's most famous anti-Nazi heroine brought to life. Sophie Scholl is the fearless activist of the underground student resistance group, The White Rose. Using historical records of her incarceration, the film re-creates the last six days of Sophie Scholl's life: a journey from arrest to interrogation, trial and sentence in 1943 Munich. Unwavering in her convictions and loyalty to her comrades, her cross- examination by the Gestapo quickly escalates into a searing test of wills as Scholl delivers a passionate call to freedom and personal responsibility that is both haunting and timeless. The White Rose The White Rose was a non-violent, intellectual resistance group in Nazi Germany, consisting of students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The group became known for an anonymous leaflet and graffiti campaign, lasting from June 1942 until February 1943, that called for active opposition to dictator Adolf Hitler's regime. -

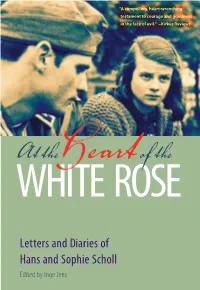

At the Heart of the White Rose: Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie

“A compelling, heart-wrenching testament to courage and goodness in the face of evil.” –Kirkus Reviews AtWHITE the eart ROSEof the Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens This is a preview. Get the entire book here. At the Heart of the White Rose Letters and Diaries of Hans and Sophie Scholl Edited by Inge Jens Translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn Preface by Richard Gilman Plough Publishing House This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com PRINT ISBN: 978-087486-029-0 MOBI ISBN: 978-0-87486-034-4 PDF ISBN: 978-0-87486-035-1 EPUB ISBN: 978-0-87486-030-6 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Contents Foreword vii Preface to the American Edition ix Hans Scholl 1937–1939 1 Sophie Scholl 1937–1939 24 Hans Scholl 1939–1940 46 Sophie Scholl 1939–1940 65 Hans Scholl 1940–1941 104 Sophie Scholl 1940–1941 130 Hans Scholl Summer–Fall 1941 165 Sophie Scholl Fall 1941 185 Hans Scholl Winter 1941–1942 198 Sophie Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 206 Hans Scholl Winter–Spring 1942 213 Sophie Scholl Summer 1942 221 Hans Scholl Russia: 1942 234 Sophie Scholl Autumn 1942 268 This is a preview. Get the entire book here. Hans Scholl December 1942 285 Sophie Scholl Winter 1942–1943 291 Hans Scholl Winter 1942–1943 297 Sophie Scholl Winter 1943 301 Hans Scholl February 16 309 Sophie Scholl February 17 311 Acknowledgments 314 Index 317 Notes 325 This is a preview. -

La Résistance Allemande Au Nazisme

La résistance allemande au nazisme Extrait du site An@rchisme et non-violence2 http://anarchismenonviolence2.org Jean-Marie Tixier La résistance allemande au nazisme - Dans le monde - Allemagne - Résistance allemande au nazisme - Date de mise en ligne : dimanche 11 novembre 2007 An@rchisme et non-violence2 Copyright © An@rchisme et non-violence2 Page 1/26 La résistance allemande au nazisme Mémoire(s) de la résistance allemande : Sophie Scholl, les derniers jours... de la plus qu'humaine ? Avec l'aimable autorisation du Festival international du Film d'histoire « J'ai appris le mensonge des maîtres, de Bergson à Barrès, qui rejetaient avec l'ennemi ce qui ne saurait être l'ennemi de la France : la pensée allemande, prisonnière de barbares comme la nôtre, et comme la nôtre chantant dans ses chaînes... Nous sommes, nous Français, en état de guerre avec l'Allemagne. Et il est nécessaire aux Français de se durcir, et de savoir même être injustes, et de haïr pour être aptes à résister... Et pourtant, il nous est facile de continuer à aimer l'Allemagne, qui n'est pas notre ennemie : l'Allemagne humaine et mélodieuse. Car, dans cette guerre, les Allemands ont tourné leurs premières armes contre leurs poètes, leurs musiciens, leurs philosophes, leurs peintres, leurs acteurs... Et ce n'est qu'en Fhttp://anarchismenonviolence2.org/ecrire/ ?exec=articles_edit&id_article=110&show_docs=55#imagesrance qu'on peut lire Heine, Schiller et Goethe sans trembler. Avant que la colère française n'ait ses égarements, et que la haine juste des hommes d'Hitler n'ait levé dans tous les coeurs français ce délire qui accompagne les batailles [...], je veux dire ma reconnaissance à la vraie Allemagne.. -

Joseph Goebbels 1 Joseph Goebbels

Joseph Goebbels 1 Joseph Goebbels Joseph Goebbels Reich propaganda minister Goebbels Chancellor of Germany In office 30 April 1945 – 1 May 1945 President Karl Dönitz Preceded by Adolf Hitler Succeeded by Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk (acting) Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda In office 13 March 1933 – 30 April 1945 Chancellor Adolf Hitler Preceded by Office created Succeeded by Werner Naumann Gauleiter of Berlin In office 9 November 1926 – 1 May 1945 Appointed by Adolf Hitler Preceded by Ernst Schlange Succeeded by None Reichsleiter In office 1933–1945 Appointed by Adolf Hitler Preceded by Office created Succeeded by None Personal details Born Paul Joseph Goebbels 29 October 1897 Rheydt, Prussia, Germany Joseph Goebbels 2 Died 1 May 1945 (aged 47) Berlin, Germany Political party National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) Spouse(s) Magda Ritschel Children 6 Alma mater University of Bonn University of Würzburg University of Freiburg University of Heidelberg Occupation Politician Cabinet Hitler Cabinet Signature [1] Paul Joseph Goebbels (German: [ˈɡœbəls] ( ); 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German politician and Reich Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. As one of Adolf Hitler's closest associates and most devout followers, he was known for his zealous orations and deep and virulent antisemitism, which led him to support the extermination of the Jews and to be one of the mentors of the Final Solution. Goebbels earned a PhD from Heidelberg University in 1921, writing his doctoral thesis on 19th century literature of the romantic school; he then went on to work as a journalist and later a bank clerk and caller on the stock exchange. -

The White Rose in Cooperation With: Bayerische Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildungsarbeit the White Rose

The White Rose In cooperation with: Bayerische Landeszentrale für Politische Bildungsarbeit The White Rose The Student Resistance against Hitler Munich 1942/43 The Name 'White Rose' The Origin of the White Rose The Activities of the White Rose The Third Reich Young People in the Third Reich A City in the Third Reich Munich – Capital of the Movement Munich – Capital of German Art The University of Munich Orientations Willi Graf Professor Kurt Huber Hans Leipelt Christoph Probst Alexander Schmorell Hans Scholl Sophie Scholl Ulm Senior Year Eugen Grimminger Saarbrücken Group Falk Harnack 'Uncle Emil' Group Service at the Front in Russia The Leaflets of the White Rose NS Justice The Trials against the White Rose Epilogue 1 The Name Weiße Rose (White Rose) "To get back to my pamphlet 'Die Weiße Rose', I would like to answer the question 'Why did I give the leaflet this title and no other?' by explaining the following: The name 'Die Weiße Rose' was cho- sen arbitrarily. I proceeded from the assumption that powerful propaganda has to contain certain phrases which do not necessarily mean anything, which sound good, but which still stand for a programme. I may have chosen the name intuitively since at that time I was directly under the influence of the Span- ish romances 'Rosa Blanca' by Brentano. There is no connection with the 'White Rose' in English history." Hans Scholl, interrogation protocol of the Gestapo, 20.2.1943 The Origin of the White Rose The White Rose originated from individual friend- ships growing into circles of friends. Christoph Probst and Alexander Schmorell had been friends since their school days. -

Vest-Tysklands Møte Med Nazifortiden På Filmlerretet

Vest-Tysklands møte med nazifortiden på filmlerretet Vegar Lillejordet Masteroppgave i historie Det humanistiske fakultetet Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Våren 2014 i Vest-Tysklands møte med nazifortiden på filmlerretet Forord Forord Jeg vil takke min flinke veileder Anders G. Kjøstvedt for verdifulle innspill, oppmuntring og trøst, og for at han ikke har ignorert meg selv om jeg som vanlig har kunnet feire St. Totteringhamsday på hans bekostning. Takk til Mads Motrøen og Iver Gabrielsen for kommentarer og korrekturlesning i sluttfasen, og til slutt takk til Kristan Toreskaas som har vært lesesalsstøtte, lunsjpartner og kaffebrygger i hele skriveperioden. Uten dere hadde dette vært en ensom og vanskelig prosess. Vegar Lillejordet Oslo, mai 2014 ii Vest-Tysklands møte med nazifortiden på filmlerretet iii Vest-Tysklands møte med nazifortiden på filmlerretet Innholdsfortegnelse Innholdsfortegnelse Forord..........................................................................................................................................ii Innholdsfortegnelse....................................................................................................................iv Innledning....................................................................................................................................1 1.0 Teori, metode og historiografi...............................................................................................5 1.1 Kan film si noe om historien?...........................................................................................5 -

Lycurgus in Leaflets and Lectures: the Weiße Rose and Classics at Munich University, 1941–45

Lycurgus in Leaflets and Lectures: The Weiße Rose and Classics at Munich University, 1941–45 NIKLAS HOLZBERG The main building of the university at which I used to teach is situated in the heart of Munich, and the square on which it stands—Geschwister-Scholl-Platz—is named after the two best-known members of the Weiße Rose, or “White Rose,” a small group of men and women united in their re- sistance to Hitler.1 On February 18, 1943, at about 11 am, Sophie Scholl and her brother Hans, both students at the university, were observed by the janitor in the central hall as they sent fluttering down from the upper floor the rest of the leaflets they had just set out on the steps of the main stair- case and on the windowsills. The man detained them and took them to the rector, who then arranged for them to be handed over to the Gestapo as swiftly as possible. Taken to the Gestapo’s Munich headquarters, they underwent several sessions of intensive questioning and—together with another member of their group, Christoph Probst, who was arrested on February 19—they were formally charged on February 21 with having committed “treasonable acts likely to ad- vance the enemy cause” and with conspiring to commit “high treason and demoralization of the troops.”2 On the morning of the following day, the Volksgerichtshof, its pre- siding judge Roland Freisler having journeyed from Berlin to Munich for the occasion, sentenced them to death. That same afternoon at 5pm—only four days after the first ar- rests—they were guillotined. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Representation of Forced Migration in the Feature Films of the Federal Republic of Germany, German Democratic Republic, and Polish People’s Republic (1945–1970) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0hq1924k Author Zelechowski, Jamie Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Representation of Forced Migration in the Feature Films of the Federal Republic of Germany, German Democratic Republic, and Polish People’s Republic (1945–1970) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Germanic Languages by Jamie Leigh Zelechowski 2017 © Copyright by Jamie Leigh Zelechowski 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Representation of Forced Migration in the Feature Films of the Federal Republic of Germany, German Democratic Republic, and Polish People’s Republic (1945–1970) by Jamie Leigh Zelechowski Doctor of Philosophy in Germanic Languages University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Todd S. Presner, Co-Chair Professor Roman Koropeckyj, Co-Chair My dissertation investigates the cinematic representation of forced migration (due to the border changes enacted by the Yalta and Potsdam conferences in 1945) in East Germany, West Germany, and Poland, from 1945–1970. My thesis is that, while the representations of these forced migrations appear infrequently in feature film during this period, they not only exist, but perform an important function in the establishment of foundational national narratives in the audiovisual sphere. Rather than declare the existence of some sort of visual taboo, I determine, firstly, why these images appear infrequently; secondly, how and to what purpose(s) existing representations are mobilized; and, thirdly, their relationship to popular and official discourses. -

Historical Review of Developments Relating to Aggression

Historical Review of Developments relating to Aggression United Nations New York, 2003 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.03.V10 ISBN 92-1-133538-8 Copyright 0 United Nations, 2003 All rights reserved Contents Paragraphs Page Preface xvii Introduction 1. The Nuremberg Tribunal 1-117 A. Establishment 1 B. Jurisdiction 2 C. The indictment 3-14 1. The defendants 4 2. Count one: The common plan or conspiracy to commit crimes against peace 5-8 3 3. Count two: Planning, preparing, initiating and waging war as crimes against peace 9-10 4. The specific charges against the defendants 11-14 (a) Count one 12 (b) Counts one and two 13 (c) Count two 14 D. The judgement 15-117 1. The charges contained in counts one and two 15-16 2. The factual background of the aggressive war 17-21 3. Measures of rearmament 22-23 4. Preparing and planning for aggression 24-26 5. Acts of aggression and aggressive wars 27-53 (a) The seizure of Austria 28-31 (b) The seizure of Czechoslovakia 32-33 (c) The invasion of Poland 34-35 (d) The invasion of Denmark and Norway 36-43 Paragraphs Page (e) The invasion of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg 44-45 (f) The invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece 46-48 (g) The invasion of the Soviet Union 49-51 (h) The declaration of war against the United States 52-53 28 6. Wars in violation of international treaties, agreements or assurances 54 7. The Law of the Charter 55-57 The crime of aggressive war 56-57 8.