Integrated Forest Vegetation Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant List Bristow Prairie & High Divide Trail

*Non-native Bristow Prairie & High Divide Trail Plant List as of 7/12/2016 compiled by Tanya Harvey T24S.R3E.S33;T25S.R3E.S4 westerncascades.com FERNS & ALLIES Pseudotsuga menziesii Ribes lacustre Athyriaceae Tsuga heterophylla Ribes sanguineum Athyrium filix-femina Tsuga mertensiana Ribes viscosissimum Cystopteridaceae Taxaceae Rhamnaceae Cystopteris fragilis Taxus brevifolia Ceanothus velutinus Dennstaedtiaceae TREES & SHRUBS: DICOTS Rosaceae Pteridium aquilinum Adoxaceae Amelanchier alnifolia Dryopteridaceae Sambucus nigra ssp. caerulea Holodiscus discolor Polystichum imbricans (Sambucus mexicana, S. cerulea) Prunus emarginata (Polystichum munitum var. imbricans) Sambucus racemosa Rosa gymnocarpa Polystichum lonchitis Berberidaceae Rubus lasiococcus Polystichum munitum Berberis aquifolium (Mahonia aquifolium) Rubus leucodermis Equisetaceae Berberis nervosa Rubus nivalis Equisetum arvense (Mahonia nervosa) Rubus parviflorus Ophioglossaceae Betulaceae Botrychium simplex Rubus ursinus Alnus viridis ssp. sinuata Sceptridium multifidum (Alnus sinuata) Sorbus scopulina (Botrychium multifidum) Caprifoliaceae Spiraea douglasii Polypodiaceae Lonicera ciliosa Salicaceae Polypodium hesperium Lonicera conjugialis Populus tremuloides Pteridaceae Symphoricarpos albus Salix geyeriana Aspidotis densa Symphoricarpos mollis Salix scouleriana Cheilanthes gracillima (Symphoricarpos hesperius) Salix sitchensis Cryptogramma acrostichoides Celastraceae Salix sp. (Cryptogramma crispa) Paxistima myrsinites Sapindaceae Selaginellaceae (Pachystima myrsinites) -

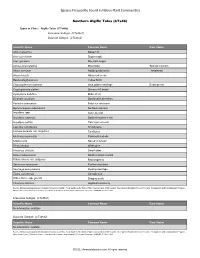

Algific Talus (Cts46)

Species Frequently Found in Native Plant Communities Southern Algific Talus (CTs46) Types in Class: Algific Talus (CTs46a) Limestone Subtype (CTs46a1) Dolomite Subtype (CTs46a2) Scientific Name Column1 Common Name Rare Status Abies balsamea Balsam fir Acer saccharum Sugar maple Acer spicatum Mountain maple Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel Special Concern Allium cernuum Nodding wild onion Threatened Arabis hirsuta Hairy rock cress Betula alleghaniensis Yellow birch Chrysosplenium iowense Iowa golden saxifrage Endangered Cryptogramma stelleri Slender cliff brake Cystopteris bulbifera Bulblet fern Dicentra cucullaria Dutchman's breeches Enemion biternatum False rue anemone Gymnocarpium robertianum Northern oak fern Impatiens spp. touch-me-not Impatiens capensis Spotted touch-me-not Impatiens pallida Pale touch-me-not Laportea canadensis Wood nettle Linnaea borealis var. longiflora Twinflower Mertensia paniculata Panicled bluebells Mitella nuda Naked miterwort Pinus strobus White pine Rhamnus alnifolia Dwarf alder Ribes hudsonianum Northern black currant Rubus idaeus var. strigosus Red raspberry Sambucus racemosa Red-berried elder Saxifraga pensylvanica Swamp saxifrage Taxus canadensis Canada yew Urtica dioica ssp. gracilis Stinging nettle Viburnum trilobum Highbush cranberry Source: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (2005). Field Guide to the Native Plant Communities of Minnesota: The Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province. Ecological Land Classification Program, Minnesota County Biological Survey, and Natural Heritage and Nongame Research Program. MNDNR St. Paul, MN. Limestone Subtype (CTs46a1) Scientific Name Column1 Common Name Rare Status No information available Dolomite Subtype (CTs46a2) Scientific Name Column1 Common Name Rare Status No information available Source: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (2005). Field Guide to the Native Plant Communities of Minnesota: The Eastern Broadleaf Forest Province. Ecological Land Classification Program, Minnesota County Biological Survey, and Natural Heritage and Nongame Research Program. -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying -

Complete Iowa Plant Species List

!PLANTCO FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUE: IOWA DATABASE This list has been modified from it's origional version which can be found on the following website: http://www.public.iastate.edu/~herbarium/Cofcons.xls IA CofC SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME PHYSIOGNOMY W Wet 9 Abies balsamea Balsam fir TREE FACW * ABUTILON THEOPHRASTI Buttonweed A-FORB 4 FACU- 4 Acalypha gracilens Slender three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 3 Acalypha ostryifolia Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 6 Acalypha rhomboidea Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU 0 Acalypha virginica Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU * ACER GINNALA Amur maple TREE 5 UPL 0 Acer negundo Box elder TREE -2 FACW- 5 Acer nigrum Black maple TREE 5 UPL * Acer rubrum Red maple TREE 0 FAC 1 Acer saccharinum Silver maple TREE -3 FACW 5 Acer saccharum Sugar maple TREE 3 FACU 10 Acer spicatum Mountain maple TREE FACU* 0 Achillea millefolium lanulosa Western yarrow P-FORB 3 FACU 10 Aconitum noveboracense Northern wild monkshood P-FORB 8 Acorus calamus Sweetflag P-FORB -5 OBL 7 Actaea pachypoda White baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Actaea rubra Red baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Adiantum pedatum Northern maidenhair fern FERN 1 FAC- * ADLUMIA FUNGOSA Allegheny vine B-FORB 5 UPL 10 Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel P-FORB 0 FAC * AEGILOPS CYLINDRICA Goat grass A-GRASS 5 UPL 4 Aesculus glabra Ohio buckeye TREE -1 FAC+ * AESCULUS HIPPOCASTANUM Horse chestnut TREE 5 UPL 10 Agalinis aspera Rough false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 10 Agalinis gattingeri Round-stemmed false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 8 Agalinis paupercula False foxglove -

Abstract on the Aspen Association of Northern Michigan

Abstract on the Aspen Association of Northern Michigan Prepared by: Christopher R . Weber Joshua G . Cohen Michael A . Kost Michigan Natural Features Inventory P.O. Box 30444 Lansing, MI 48909-7944 For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Forest, Minerals, and Fire Management Division Wildlife Division September 30, 2006 Report Number 2006-16 Cover Photograph: Young aspen clones in the eastern Upper Peninsula, Michigan. All photos by Christopher R. Weber unless otherwise noted. Overview Range This document provides a brief discussion of the aspen Trembling aspen has the most extensive range of any association of Michigan, detailing this system’s North American tree (Barnes et al. 1998). Its native landscape and historical context, range, ecological range covers a large swath from the Atlantic Ocean to processes, characteristic vegetation and fauna, and the Pacific Ocean, spreading from its southern limit in threatened and endangered species. In addition, northern Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania north potential options and strategies are suggested for to the Hudson Bay. Trembling aspen’s range reaches enhancing biodiversity of managed aspen associations into the northern and southern Rocky Mountains, and and for restoring these systems to later successional all the way west through Canada and east to forest types. Newfoundland and Labrador (Perala 1990). Throughout the south and west Rocky Mountains, trembling aspen is found as a late-successional species, having long-lived clones, sometimes with Introduction thousands of stems that expand over large acreages The aspen association occurs throughout the Great (Barnes et al. 1998). Aspen has been found to Lakes region as a disturbance dependent vegetation compete with prairies in the Canadian west (Bird assemblage. -

1.4. Northern Temperate and Boreal Forests in Ontario 11 1.4.1

Effects of Intensification of Silviculture on Plant Diversity in Northern Temperate and Boreal Forests of Ontario, Canada by Frederick Wayne Bell A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science Guelph, Ontario, Canada © F. Wayne Bell, January, 2015 ABSTRACT EFFECTS OF INTENSIFICATION OF SILVICULTURE ON PLANT DIVERSITY IN NORTHERN TEMPERATE AND BOREAL FORESTS OF ONTARIO, CANADA Frederick Wayne Bell Advisors: University of Guelph, 2015 Professor S. Hunt Professor S. G. Newmaster Professor M. Anand Dr. I. Aubin Dr. J. A. Baker This thesis is an investigation of the intensification of silviculture has long presented a conundrum to forest managers in the northern temperate and boreal forests of Ontario, Canada aiming to sustainably produce wood fibre and conserve biodiversity. Although intensive silviculture has long been viewed as a threat to biodiversity, it is also considered as a means to increase wood fibre production. In this thesis I determine the nature of the biodiversity– silviculture intensity relationships and improve our understanding of the mechanisms that underpin these relationships. More specifically, studied (i) compositional and functional biodiversity-silviculture intensity relationships, (ii) the relative influence of silviculture on species richness, (iii) effects of intensification of silviculture on functional response groups, and (iv) susceptibility to invasion. My results are based on fifth-year post-harvest NEBIE plot network data. Initiated in 2001, the NEBIE plot network is the only study in North America that provides a gradient of silviculture intensities in northern temperate and boreal forests. The NEBIE plot network is ii located in northern temperate and boreal forests near North Bay, Petawawa, Dryden, Timmins, Kapuskasing, and Sioux Lookout, Ontario, Canada. -

Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis Abaimov, A.P., 2010: Geographical Distribution and Ackerly, D.D., 2009: Evolution, origin and age of Genetics of Siberian Larch Species. In Osawa, A., line ages in the Californian and Mediterranean flo- Zyryanova, O.A., Matsuura, Y., Kajimoto, T. & ras. Journal of Biogeography 36, 1221–1233. Wein, R.W. (eds.), Permafrost Ecosystems. Sibe- Acocks, J.P.H., 1988: Veld Types of South Africa. 3rd rian Larch Forests. Ecological Studies 209, 41–58. Edition. Botanical Research Institute, Pretoria, Abbadie, L., Gignoux, J., Le Roux, X. & Lepage, M. 146 pp. (eds.), 2006: Lamto. Structure, Functioning, and Adam, P., 1990: Saltmarsh Ecology. Cambridge Uni- Dynamics of a Savanna Ecosystem. Ecological Stu- versity Press. Cambridge, 461 pp. dies 179, 415 pp. Adam, P., 1994: Australian Rainforests. Oxford Bio- Abbott, R.J. & Brochmann, C., 2003: History and geography Series No. 6 (Oxford University Press), evolution of the arctic flora: in the footsteps of Eric 308 pp. Hultén. Molecular Ecology 12, 299–313. Adam, P., 1994: Saltmarsh and mangrove. In Groves, Abbott, R.J. & Comes, H.P., 2004: Evolution in the R.H. (ed.), Australian Vegetation. 2nd Edition. Arctic: a phylogeographic analysis of the circu- Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, pp. marctic plant Saxifraga oppositifolia (Purple Saxi- 395–435. frage). New Phytologist 161, 211–224. Adame, M.F., Neil, D., Wright, S.F. & Lovelock, C.E., Abbott, R.J., Chapman, H.M., Crawford, R.M.M. & 2010: Sedimentation within and among mangrove Forbes, D.G., 1995: Molecular diversity and deri- forests along a gradient of geomorphological set- vations of populations of Silene acaulis and Saxi- tings. -

Report on the Conservation Status of Mertensia Bella (Oregon Bluebells) in Idaho

Report on the Conservation Status of Mertensia bella (Oregon bluebells) in Idaho by Juanita Lichthardt Conservation Data Center Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program December 1992 Idaho Department of Fish and Game 600 South Walnut, P.O. Box 25 Boise, ID 83707 Jerry Conley, Director Cooperative Challenge Cost-share Project Clearwater National Forest Nez Perce National Forest Idaho Department of Fish and Game Purchase Order Nos. 43-0276-1-0573 (CNF) 93-0295-2-0384 (NPNF) I- Species information 1. Classification and nomenclature A. Species 1. Scientific name a. Binomial: Mertensia bella Piper b. Full bibliographic citation: C.V. Piper. 1918. New Plants of the Pacific Northwest. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 31:75-78. c. Type specimen: M.E. Peck (5811) Horse Pasture Mt., 10 miles southwest of McKenzie Bridge, Lane Co., Oregon. 2. Pertinent synonym(s): Mertensia siskiyouensis (Williams 1937) 3. Common name: Oregon bluebells 4. Size of genus: The genus Mertensia contains 35-40 species native to extratropical Eurasia and North America (Cronquist 1959). Williams (1937) recognized 24 species in North America, most of them in the western United States. The highest concentration of Mertensia species occurs in the western half of Colorado, with a second, smaller concentration in northern Idaho and adjacent Montana, Wyoming, Washington, and Oregon. Oregon bluebells is a distinctive species apparently without close relatives (Cronquist 1959). B. Family classification 1. Family name: Boraginaceae 2. Pertinent family synonyms: None 3. Common name for family: Borage C. History of knowledge of taxon: The type specimen for Mertensia bella was collected in the Cascade Mountains, in Lane County, Oregon by Peck in 1914 (Lorain 1988). -

2019-Identification

Carrot Family (Apiaceae) Giant hogweed ● Heracleum mantegazzianum Invasiveness Rank: 81 points Species Code: HEMA17 General Information: Biennial or perennial 3-4.5 m tall Typically die after flowering Description: Stems Hollow Reddish spots Bristles Leaves Compound Inflorescence Umbels up to 75 cm in diameter Flowers small and white Fruits Flat, oval, dry Habitat: damp locations, along rivers and streams, disturbed areas including waste places and roadsides Distribution: Pacific maritime; only one population known in Kake, which appears to have been eradicated. Comparison to native H. maximum: Height Umbel Width Leaves H. mantegazzianum < 4.5 m < 75 cm Compound H. maximum < 1.8 m <30 cm Palmately lobed 115 Touch-me-not Family (Balsaminaceae) Ornamental jewelweed ● Impatiens glandulifera Invasiveness Rank: 82 points Species Code: IMGL General Information: 0.9-1.8 m tall Entire plant has purple or reddish tinge Description: Stems Hollow Leaves Mostly opposite or whorled Serrated margins Petioles with large glands Inflorescence White, pink, red or purple With a 4-5 mm long spur Fruits © 2015 AKNHP b- Dehisce explosively (ripe seeds shoot out when touched) Habitat: riparian areas, wetlands, beach meadows; escapes from gardens Distribution: few sites in the Pacific maritime and interior boreal regions; Kenai, Anchorage, Juneau, Skagway, Haines; in and near Fairbanks and Salcha Touch-me-not ● Impatiens noli-tangere General Information: 0.2-0.8 m tall Smaller than I. glandulifera Description: Stems Watery to fleshy Leaves Alternate Margins coarsely toothed Inflorescence Yellow-orange with brown spots With a 6-10 mm long spur Fruits Dehisce explosively Habitat: moist forests and stream banks Distribution: Pacific maritime and interior boreal regions 116 Other Families Key to select common, small, blue-flowered species: 1a. -

Washington Flora Checklist a Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Washington State Hosted by the University of Washington Herbarium

Washington Flora Checklist A checklist of the Vascular Plants of Washington State Hosted by the University of Washington Herbarium The Washington Flora Checklist aims to be a complete list of the native and naturalized vascular plants of Washington State, with current classifications, nomenclature and synonymy. The checklist currently contains 3,929 terminal taxa (species, subspecies, and varieties). Taxa included in the checklist: * Native taxa whether extant, extirpated, or extinct. * Exotic taxa that are naturalized, escaped from cultivation, or persisting wild. * Waifs (e.g., ballast plants, escaped crop plants) and other scarcely collected exotics. * Interspecific hybrids that are frequent or self-maintaining. * Some unnamed taxa in the process of being described. Family classifications follow APG IV for angiosperms, PPG I (J. Syst. Evol. 54:563?603. 2016.) for pteridophytes, and Christenhusz et al. (Phytotaxa 19:55?70. 2011.) for gymnosperms, with a few exceptions. Nomenclature and synonymy at the rank of genus and below follows the 2nd Edition of the Flora of the Pacific Northwest except where superceded by new information. Accepted names are indicated with blue font; synonyms with black font. Native species and infraspecies are marked with boldface font. Please note: This is a working checklist, continuously updated. Use it at your discretion. Created from the Washington Flora Checklist Database on September 17th, 2018 at 9:47pm PST. Available online at http://biology.burke.washington.edu/waflora/checklist.php Comments and questions should be addressed to the checklist administrators: David Giblin ([email protected]) Peter Zika ([email protected]) Suggested citation: Weinmann, F., P.F. Zika, D.E. Giblin, B. -

Plant List Browder Ridge

*Non-native Browder Ridge Plant List as of 7/12/2016 compiled by Tanya Harvey T14S.R6E.S10,11 westerncascades.com FERNS & ALLIES Abies procera Ribes lacustre Athyriaceae Picea engelmannii Ribes lobbii Athyrium filix-femina Pinus contorta var. latifolia Ribes sanguineum Blechnaceae Pinus monticola Ribes viscosissimum Blechnum spicant Pseudotsuga menziesii Rhamnaceae Cystopteridaceae Tsuga heterophylla Ceanothus velutinus Cystopteris fragilis Tsuga mertensiana Rosaceae Gymnocarpium disjunctum Taxaceae Amelanchier alnifolia Dennstaedtiaceae Taxus brevifolia Holodiscus discolor Pteridium aquilinum TREES & SHRUBS: DICOTS Prunus emarginata Dryopteridaceae Adoxaceae Rosa gymnocarpa Polystichum lonchitis Sambucus racemosa Rubus lasiococcus Polystichum munitum Araliaceae Rubus leucodermis Lycopodiaceae Oplopanax horridus Rubus parviflorus Lycopodium clavatum Berberidaceae Rubus spectabilis Polypodiaceae Berberis nervosa Rubus ursinus Polypodium sp. (Mahonia nervosa) Sorbus scopulina Pteridaceae Betulaceae Sorbus sitchensis Adiantum aleuticum Alnus viridis ssp. sinuata (Adiantum pedatum var. aleuticum) (Alnus sinuata) Spiraea splendens (Spiraea densiflora) Aspidotis densa Corylus cornuta var. californica Salicaceae Cheilanthes gracillima Caprifoliaceae Salix sitchensis Symphoricarpos albus Cryptogramma acrostichoides (Cryptogramma crispa) Symphoricarpos mollis Sapindaceae (Symphoricarpos hesperius) Acer circinatum Selaginellaceae Selaginella scopulorum Celastraceae Acer glabrum var. douglasii (Selaginella densa var. scopulorum) Paxistima myrsinites -

FERNS and FERN ALLIES Dittmer, H.J., E.F

FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Dittmer, H.J., E.F. Castetter, & O.M. Clark. 1954. The ferns and fern allies of New Mexico. Univ. New Mexico Publ. Biol. No. 6. Family ASPLENIACEAE [1/5/5] Asplenium spleenwort Bennert, W. & G. Fischer. 1993. Biosystematics and evolution of the Asplenium trichomanes complex. Webbia 48:743-760. Wagner, W.H. Jr., R.C. Moran, C.R. Werth. 1993. Aspleniaceae, pp. 228-245. IN: Flora of North America, vol.2. Oxford Univ. Press. palmeri Maxon [M&H; Wagner & Moran 1993] Palmer’s spleenwort platyneuron (Linnaeus) Britton, Sterns, & Poggenburg [M&H; Wagner & Moran 1993] ebony spleenwort resiliens Kunze [M&H; W&S; Wagner & Moran 1993] black-stem spleenwort septentrionale (Linnaeus) Hoffmann [M&H; W&S; Wagner & Moran 1993] forked spleenwort trichomanes Linnaeus [Bennert & Fischer 1993; M&H; W&S; Wagner & Moran 1993] maidenhair spleenwort Family AZOLLACEAE [1/1/1] Azolla mosquito-fern Lumpkin, T.A. 1993. Azollaceae, pp. 338-342. IN: Flora of North America, vol. 2. Oxford Univ. Press. caroliniana Willdenow : Reports in W&S apparently belong to Azolla mexicana Presl, though Azolla caroliniana is known adjacent to NM near the Texas State line [Lumpkin 1993]. mexicana Schlechtendal & Chamisso ex K. Presl [Lumpkin 1993; M&H] Mexican mosquito-fern Family DENNSTAEDTIACEAE [1/1/1] Pteridium bracken-fern Jacobs, C.A. & J.H. Peck. Pteridium, pp. 201-203. IN: Flora of North America, vol. 2. Oxford Univ. Press. aquilinum (Linnaeus) Kuhn var. pubescens Underwood [Jacobs & Peck 1993; M&H; W&S] bracken-fern Family DRYOPTERIDACEAE [6/13/13] Athyrium lady-fern Kato, M. 1993. Athyrium, pp.