Sushi 1 Sushi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miso Soup Yield: 4

Miso Soup Yield: 4 The base of a good miso soup begins with the dashi and is characterized by the different types of miso used. Miso is a thick paste produced from fermenting, rice, soybeans or barley. Miso can range in varying complexities and saltiness and is commonly identified by their colors from the less salty and sweet white (shiro) miso to red (mugi or sendai) to dark (hatcho). Dashi is Japanese stock made using the konbu or kombu, dried giant kelp and katsuobushi – wispy paper thin flakes from dried bonito fish. Dashi stock can be simmered once, and is called ichiban dashi or first dashi and is used for clear simple soups. This same dashi can be simmered again to make niban dashi or second dashi to give the soup a fuller flavor. Niban dashi is used for miso soup. Homemade Dashi Yield: 4 cups or 1 quart 4 cups cold water water 2 pieces 4-inch premium konbu or kombu ( dried kelp) 1/3 cup katsuobushi shaved dried bonito flakes 1. Make the first dash (ichiban dashi): Fill a saucepan with cold water and soak the konbu. Heat until steam is rising off the pot. Do not allow the water to boil as it will turn the dashi bitter. Just before the dashi begins to boil, turn off the heat and take the konbu out and set it aside. 2. Add the katsuobushi flakes and simmer for a couple of minutes. Take it off heat and strain to remove the katsuobushi flakes. This is your first dashi and at this stage can be used to make clear simple soups. -

Autumn Omakase a TASTING MENU from TATSU NISHINO of NISHINO

autumn omakase A TASTING MENU FROM TATSU NISHINO OF NISHINO By Tatsu Nishino, Hillel Cooperman Photographs by Peyman Oreizy First published in 2005 by tastingmenu.publishing Seattle, WA www.tastingmenu.com/publishing/ Copyright © 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publisher. Photographs © tastingmenu and Peyman Oreizy Autumn Omakase By Tatsu Nishino, Hillel Cooperman, photographs by Peyman Oreizy The typeface family used throughout is Gill Sans designed by Eric Gill in 1929-30. TABLE OF CONTENTS Tatsu Nishino and Nishino by Hillel Cooperman Introduction by Tatsu Nishino Autumn Omakase 17 Oyster, Salmon, Scallop Appetizer 29 Kampachi Usuzukuri 39 Seared Foie Gras, Maguro, and Shiitake Mushroom with Red Wine Soy Reduction 53 Matsutake Dobinmushi 63 Dungeness Crab, Friseé, Arugula, and Fuyu Persimmon Salad with Sesame Vinaigrette 73 Hirame Tempura Stuffed with Uni, Truffle, and Shiso 85 Hamachi with Balsamic Teriyaki 95 Toro Sushi, Three Ways 107 Plum Wine Fruit Gratin The Making of Autumn Omakase Who Did What Invitation TATSU NISHINO AND NISHINO In the United States, ethnic cuisines generally fit into convenient and simplistic categories. Mexican food is one monolithic cuisine, as is Chinese, Italian, and of course Japanese. Every Japanese restaurant serves miso soup, various tempura items, teriyaki, sushi, etc. The fact that Japanese cuisine is multi-faceted (as are most cuisines) and quite diverse doesn’t generally come through to the public—the American homogenization machine reduces an entire culture’s culinary contributions to a simple formula that can fit on one menu. -

Sushi Global«: Zwischen J-Branding Und Kulinarischem Nationalismus

»Sushi global«: Zwischen Jbranding und kulinarischem Nationalismus Sushi Gone Global: Between J-branding and Culinary Nationalism Dorothea Mladenova Based on a historical outline of how Sushi travelled from Japan via the U.S. to Europe with a special focus on Germany, it is argued that today there exist at least two forms of Sushi, the »original« and the »glocal«, both of which have their own history and legitimacy. By applying the globalization theories of Appadurai (2008), Ritzer (2008) and Ng (2001) it is shown how global Sushi emerged from Japanese Sushi while be- coming an independent item and hybridizing itself. Therefore, Sushi does not fit in the narrow framework of »national« or »ethnic« cuisine any more. The article states that by referring to global Sushi variations as »fake«, the Japanese agents who advocate a »clean-up« of the global sushi economy are ignoring that the two different types can- not be judged by the same standard, because they follow different rules and patterns of consumption and thereby serve different functions. 1. Einleitung Ist von »japanischem Essen« die Rede, so fällt zumeist auch sehr bald das Stichwort »Sushi«. Zwar spielt es in Japan selbst sowohl im häuslichen als auch im gastrono- mischen Bereich eine eher untergeordnete Rolle, da zum einen die Zubereitung von nigirizushi und makizushi als eine Meisterleistung angesehen wird, so dass man sich daheim nur an vereinfachte Varianten wie chirashizushi oder temakizushi1 1. Unter nigirizushi werden von der Hand geformte Reisquader mit einer Scheibe frischen Fischs verstanden. Mit makizushi ist in Algen gerolltes Sushi gemeint. Beim chirashizushi werden der 276 Gesellschaft traut, und zum anderen weil in der Gastronomie Sushi entweder als haute cuisine für besondere Anlässe oder als Familienspaß im Schnellrestaurant gilt, und auch dies erst seit der Rezession in den 1990er Jahren (Silva und Yamao 2006). -

Signature Sushi Rolls Greek Roll

sushi menu Early history The original type of sushi, known today as narezushi, was first developed in Southeast Asia and spread to south China before introduced to Japan sometime around the 8th century. Fish was salted and wrapped in fermented rice, a traditional lacto-fermented rice dish. Narezushi was made of this gutted fish stored in fermented rice for months at a time for preservation. The fermentation of the rice prevented the fish from spoiling. The fermented rice was discarded and fish was the only part consumed. This early type of sushi became an important source of protein for the Japanese. The Japanese preferred to eat fish with rice, known as namanare or. During the Muromachi period namanare was the most popular type of sushi. Namanare was partly raw fish wrapped in rice, consumed fresh, before it changed flavor. This new way of consuming fish was no longer a form of preservation but rather a new dish in Japanese cuisine. During the Edo period, a third type of sushi was introduced, haya-zushi. Haya-zushi was assembled so that both rice and fish could be consumed at the same time, and the dish became unique to Japanese culture. It was the first time that rice was not being used for fermentation. Rice was now mixed with vinegar, with fish, vegetables and dried foodstuff added. This type of sushi is still very popular today. Each region utilizes local flavors to produce a variety of sushi that has been passed down for many generations. When Tokyo was still known as Edo in the early 19th century, mobile food stalls run by street vendors became popular. -

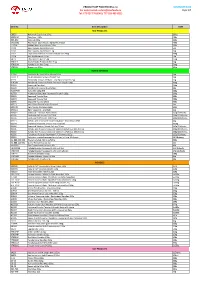

NOVEMBER 2020 Page

PRODUCT LIST TAKO FOODS s.r.o NOVEMBER 2020 For orders email: [email protected] Page 1/7 Tel: 773 027 776 (ENG), 777 926 495 (CZE) Item No. Item Description UoM RICE PRODUCTS 08930 Hakumaki Sushi rice 10 kg 10 kg 303013A Rice flour 400g 400g 839-840 Shiokoji 220g 220g CH16032 Rice Paper 22cm Round Spring-Roll 400g 400g J1371A Malted Rice - Kome Kouji 200g 200g J3100 Rice Toyama Koshihikari 5kg 5kg J3101 Rice Toyama Koshihikari 1 kg 1kg J3102 Toyama Koshihikari Funwari Gohan rice 200g 200g J3104 Rice Akitakomachi 5 kg 5kg J4075 Thai Jasmine Rice 25 kg 25kg YTK019 Koshi Yutaka Premium Rice 5 kg 5kg YTK023G Yutaka Sushi Rice 500g 500g YTK033 Brown rice 10kg 10kg NORI & SEAWEED 17164 Dashi Konbu Dried Kelp (Akaya) 1 kg 1kg CN-11-1 Chuka Wakame Seaweed salad 1kg 1kg K1131 Yamanaka Tokuyo Mehijiki - Dry Hijiki Seaweed 25g 25g K1450B Powdered Seaweed Aonori Premium Grade 100g 100g K1619 Seaweed Ogo Nori 500g K1628 Shredded Seaweed Kizami Nori 50g K1697WR Kaiso Mix 100g WR 100g K1703 Ariake Yaki Bara Nori Seaweed Grade A 100g 100g K2903 Seaweed Tosaka Blue 500g K2904 Seaweed Tosaka Red 500g K2905 Seaweed Tosaka White 500g K3214 Kelp Yama Dashi Konbu (Sokusei) 1kg K3217B Kelp Ma Konbu (Hakodate) 500g K3261A Hijiki Seawood - Me Hijiki 1kg K33021 Seaweed - Yakinori Aya Full Size 125g/50sheets K3305 Sushi nori full sheets 100/230G 230g/100sheets K3306 Sushi nori half sheets 100/125g 125g/100sheets K3313 Kofuku nori Seasoned seaweed Ajitsuke Nori Ohavo 8Pkt 24g K3314 Seasoned seaweed sesame nori chips 8G 30/8g K3340 Seaweed Yakinori Miyabi full -

Eating the Other. a Semiotic Approach to the Translation of the Culinary Code

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI TORINO (UNITO) UNIVERSITÀ DELLA SVIZZERA ITALIANA (USI) Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici (UNITO) / Faculty of Communication Sciences (USI) DOTTORATO DI RICERCA (IN CO-TUTELA) IN: Scienze del Linguaggio e della Comunicazione (UNITO) / Scienze della Comunicazione (USI) CICLO: XXVI (UNITO) TITOLO DELLA TESI: Eating the Other. A Semiotic Approach to the Translation of the Culinary Code TESI PRESENTATA DA: Simona Stano TUTORS: prof. Ugo Volli (UNITO) prof. Andrea Rocci (USI) prof. Marcel Danesi (UofT, Canada e USI, Svizzera) COORDINATORI DEL DOTTORATO: prof. Tullio Telmon (UNITO) prof. Michael Gilbert (USI) ANNI ACCADEMICI: 2011 – 2013 SETTORE SCIENTIFICO-DISCIPLINARE DI AFFERENZA: M-FIL/05 EATING THE OTHER A Semiotic Approach to the Translation of the Culinary Code A dissertation presented by Simona Stano Supervised by Prof. Ugo Volli (UNITO, Italy) Prof. Andrea Rocci (USI, Switzerland) Prof. Marcel Danesi (UofT, Canada and USI, Switzerland) Submitted to the Faculty of Communication Sciences Università della Svizzera Italiana Scuola di Dottorato in Studi Umanistici Università degli Studi di Torino (Co-tutorship of Thesis / Thèse en Co-tutelle) for the degree of Ph.D. in Communication Sciences (USI) Dottorato in Scienze del Linguaggio e della Comunicazione (UNITO) May, 2014 BOARD / MEMBRI DELLA GIURIA: Prof. Ugo Volli (UNITO, Italy) Prof. Andrea Rocci (USI, Switzerland) Prof. Marcel Danesi (UofT, Canada and USI, Switzerland) Prof. Gianfranco Marrone (UNIPA, Italy) PLACES OF THE RESEARCH / LUOGHI IN CUI SI È SVOLTA LA RICERCA: Italy (Turin) Switzerland (Lugano, Geneva, Zurich) Canada (Toronto) DEFENSE / DISCUSSIONE: Turin, May 8, 2014 / Torino, 8 maggio 2014 ABSTRACT [English] Eating the Other. A Semiotic Approach to the Translation of the Culinary Code Eating and food are often compared to language and communication: anthropologically speaking, food is undoubtedly the primary need. -

WHY SUSHI? IT’S HOT! Simplicity and Mystique Is What It’S All About

WHY SUSHI? IT’S HOT! Simplicity and mystique is what it’s all about. Sushi is delicious, healthy and it is all the rage! Judging by its popularity around the country, Sushi is still hot (or shall we say cold). Welcome to our love affair! When most people hear the word “Sushi”, they immediately think of raw fish. In truth, dishes made with raw fish are called “Sashimi”. The definition of Sushi is any dish made with vinegar-rice, which may or may not include raw fish. The Evolution of Sushi In the early 1800’s a man by the name of Hanaya Yohei conceived a major change in the production and presentation of his sushi. No longer wrapping the fish in rice, he placed a piece of fresh fish on top of an oblong shaped piece of seasoned rice. Today, we call this style ‘nigiri sushi’ (finger sushi). At that time, sushi was served from sushi stalls on the street and was meant to be a snack or quick bite to eat on the go. Served from his stall, this was not only the first of the real ‘fast food’ sushi, but quickly became wildly popular. From his home in Edo, this style of serving sushi rapidly spread throughout Japan, aided by the Great Kanto earthquake in 1923, as many people lost their homes and businesses and moved from Tokyo. After World War Two, the sushi stalls were shut down and moved indoors, to more sanitary conditions. More formal seating was later provided and sushi changed from ‘fast food’ to a true dining experience. -

Cardinal Sushi.Pdf

Yachting Parsifal Dear Chef, In the Catalogue below you will find first, the photos of the products along with their code and at the end of the document a full description. Kind regards The Parsifal Supplies team Yachting Parsifal Yachting Japan (Sushi) Parsifal 3 Japan (Sushi) Ιαπωνία (Sushi) Anago Topping 25Pcs 160 gr Akaya Bamboo Sushi Maki Mat 21X24cm 1 Beer Asahi 330 ml Beer Kirin 330 ml Σεκ. Dayat 047025 068860 069447 061236 Καηεςπγκέλν Χαιάθη H Θαπσληθή ζαιαζζηλό κπακπνύ γηα δεκνθηιέζηεξ κπύξα κε ρέιη. ζνύζη. ε κπύξα ζηελ ήπηα, Θαπσλία από ηζνξξνπεκέλε ην 1987. Alc. γεύζε. Alc. 5% vol. 5% vol. Beer Sapporo 330 ml Beni Shoga 1000 gr Akaya Black Cod Global 1000 gr Bonito Flakes Katsuo Boshi 500 gr Wadaq 067849 045748 046981 080480 Η παιαηόηεξε Ρόδ πίθια Kαηεςπγκέλνο Καπληζηή θαη κία από ηδίληδεξ. καύξνο απνμεξακέλε ηηο θαιύηεξεο κπαθαιηάξνο. παιακίδα ζε κπύξεο ηεο ληθάδεο. Θαπσλίαο. Alc. 4.7% vol. Yachting Bread Crumbs 200 gr Obento Bread Crumbs 10000 gr Obento Buckwheat Noodles 300 gr Sukina Children Chopstick Bear 22cm 1 Σεκ. 036739 068235 056584 030645 Ψηρνπιάθηα Ψίρνπια Ννύληιο από Παηδηθό Ψσκηνύ γηα ςσκηνύ γηα θαγόππξν. ηζνπζηηθ Παλάξηζκα. παλάξηζκα. 22cm κε ζρέδην αξθνπδάθη. Parsifal 4 Japan (Sushi) Ιαπωνία (Sushi) Children Chopstick Lucky Cat 22cm Children Chopstick Panda 22cm Pink Chili Pepper Assorted Nanami Chopsticks Bamboo Various Colours, Chopsticks Bamboo, Motive Flowers, 1 Σεκ. 1 Σεκ. Togarashi 300 gr S&B Motive Flowers 5 Pair Jade Temple 1 Birds 5 Pair Jade Temple 1 Set Set 030409 030393 080466 071259 071235 Παηδηθό Παηδηθό Θαπσληθό εη από 5 εη από 5 ηζνπζηηθ Σζνπζηηθ κείγκα μύιηλα μύιηλα 22εθ.κε 22εθ. -

Sushiadvanceblad 0.Pdf

The Complete Guide to Sushi & Sashimi Contents Bamboo Sushi Mats Red Snapper (Tai) Preparing Shrimp Recipe: Chopped (Makisu) Fluke (Hirame) for Hand-Shaped Chirashi (Bara Acknowledgments Omelette Pans Mackerel (Saba/Aji) Sushi (Nigiri) Chirashi) Introduction (Makiyakinabe) Recipe: Cured Preparing to Cook Recipe: Five- Rice Cookers Mackerel Peeling Ingredient Chirashi The Story of Sushi Wooden Rice Bowls Octopus (Tako) Deveining and (Gomuko Chirashi) and Paddle (Hangiri Squid (Ika) Preparing for Equipment and Shamoji) Hand-Shaped Sushi Pressed Sushi Traditional and Shellfish (Nigiri) (Oshizushi) Western-Style Ingredients Shrimp (Ebi) Opening Bi-Valves Recipe: Pressed Knives Rice Recipe: Shrimp Clams Box-Shape Sushi Japanese Vinegar Pound Cake Scallops (Oshizushi) Manufacturing Sake (Kasutera) Cleaning Soft Shell Recipe: Log-Shaped Handle Types Mirin Scallop (Hotate) Crabs Sushi (Bouzushi) Traditional Japanese Recipe: Sushi Vinegar King Crab (Kani) Shelling King Crab Knives Nori Clams (Orange: Legs Rolled Sushi Yanagiba Konbu Aoyagi/Giant: Cleaning Squid (Maki) Deba and Kodeba Cured, Dried, and Mirugai) Cleaning and Introduction Usuba and Kamagata Fermented Bonito Sea Urchin (Uni) Preparing Octopus Thin Rolls (Hosomaki) Usuba (Katsuoboshi) Salmon Roe (Ikura) Recipe: Cucumber Ribbon Cut Recipe: Dashi Recipe: Salmon Roe Sliced Raw Fish Roll (Kappamaki) (Katsuramuki) Recipe: Miso Soup Dressing and Seafood Recipe: Tuna Roll Kirutske Soy Sauce Flying Fish Roe (Sashimi) (Tekkamaki) Western Equivalents Recipe: Soy (Tobiko) Fish Cuts Recipe: Inside -

"Authenticity" of Sushi: Modernizing and Transforming a Japanese Food

The "Authenticity" of Sushi: Modernizing and Transforming a Japanese Food Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Yang, Wen Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 17:12:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/297043 THE "AUTHENTICITY" OF SUSHI: TRANSFORMING AND MODERNIZING A JAPANESE FOOD by Wen Yang ____________________________ A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2013 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the author. SIGNED: Wen Yang APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: 07/01/2013 Noel J. Pinnington Date Associate Professor Department of East Asian Studies 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my academic advisor Dr. -

Food for the Eye, the Body & the Soul

SUSHI Food for the eye, the body & the soul Ole G. Mouritsen SUSHI Food for the eye, the body & the soul Graphic design and photography Jonas Drotner Mouritsen Water colours Tove Nyberg Translation and adaptation to English Mariela Johansen Sushi • Food for the eye, the body & the soul Author Ole G. Mouritsen Graphic design and photography Jonas Drotner Mouritsen Water colours Tove Nyberg Translation and adaptation to English Mariela Johansen ISBN: 978-1-4419-0617-5 e-ISBN: 978-1-4419-0618-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009931802 © 2009 Springer Science+Business Media B.V. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, record ing or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Printed in the US on acid-free paper 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 springer.com Menu • • • Sushi – Zen, passion, science & wellness Sushi and Zen What is sushi? • Life, food & molecules The molecules of life Sensory perception • “Something from the sea & something from the mountains” ‘The fruit of the sea’: fish and shellfish ‘Plants from the sea’ Soybeans: tofu, shōyu, and miso Rice, rice wine, and rice vinegar Spices in Japanese cuisine • Storage & conservation Fish and shellfish Tsukemono – the art of pickling • Tools, preparation & presentation Tools for making sushi -

Carte Mars 2018

NOS SUSHIS Nos makis Un riz onctueux et fondant, la douceur d'une algue de nori et un coeur gourmand à souhait ! Nos California Rolls Vendus par 8 pièces : 6 + 2 offertes Inventé à Los Angeles par des chefs japonais, le California Roll est la combinaison entre l’algue de nori, une garniture gourmande et un enrobage de riz fondant. CHÈVRE MIEL CREVETTE AVOCAT POULET SPICY POULET CRISPY SAUMON AVOCAT Fromage de chèvre frais, miel Crevette tempura & avocat Poulet, avocat, sauce mayonnaise Poulet, oignons frits, avocat Saumon fumé & avocat & salade 5,90 € pimentée, chips de wasabi & mayonnaise 4,90 € 5,90 € 5,90 € 5,90 € SAUMON CRISPY SURIMI AVOCAT THON AVOCAT THON CUIT AVOCAT VEGGIE Saumon fumé, fromage frais, Surimi, avocat & masago Thon & avocat Thon cuit, avocat & fromage frais Concombre, avocat & fromage concombre & oignons frits 4,90 € 5,50 € 5,20 € frais aux herbes 5,90 € 4,90 € Nos Signatures Rolls Des créations gourmandes à souhait ! DRAGON SAUMON CHEESE Crevettes Tempura, asperges, avocat, Saumon fumé, fromage frais & sauce mayonnaise pimentée, tobiko, aneth sésame 5,20 € 9,90 € Disponible uniquement en salle FOIE GRAS ITALIEN Fois gras, cont de gues, pralin Jambon italien, pesto, parmesan, & pain d’épice salade & basilic RED DRAGON 7,20 € 6,90 € Crevettes tempura, avocat, chips au CRABE AVOCAT wasabi, thon teryaki, tobiko, sésame & Crabe des neiges, avocat, INDIEN sauce mayonnaise pimentée Poulet, sauce curry, avocat, mayonnaise & masago carottes, salade & chips vitelotte 10,90 € 5,90 € Disponible uniquement en salle 6,90 € Spring