Beyond Nigiri and Anisakiasis, the Tale of Sushi: History and Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post 60 Recipes

Post 60 Recipes Cooking Measurement Equivalents 16 tablespoons = 1 cup 12 tablespoons = 3/4 cup 10 tablespoons + 2 teaspoons = 2/3 cup 8 tablespoons = 1/2 cup 6 tablespoons = 3/8 cup 5 tablespoons + 1 teaspoon = 1/3 cup 4 tablespoons = 1/4 cup 2 tablespoons = 1/8 cup 2 tablespoons + 2 teaspoons = 1/6 cup 1 tablespoon = 1/16 cup 2 cups = 1 pint 2 pints = 1 quart 3 teaspoons = 1 tablespoon 48 teaspoons = 1 cup Deviled Eggs Chef: Phil Jorgensen 6 dozen eggs 1 small onion 1 celery hot sauce horse radish mustard pickle relish mayonnaise Worcestershire sauce Boil the 6 dozen eggs in salty water While the eggs are boiling dice/slice/ grate, the celery and onion into itty bitty pieces put them in the bowl. Eggs get cooled best with lots of ice and more salt Peel and half the eggs. Drop the yokes in the bowl with onion / celery add mustard, mayo, relish Begin whupping then add some pepper 1/4 hand and 1 teaspoon of salt. Add some Worcestershire sauce 2-4 shakes Add some hot sauce 2-3 shakes. Add about 1/4 to 1/2 cup of horse radish. Keep whupping till thoroughly mixed then stuff eggs as usual. Ham Salad Chef: Brenda Kearns mayonnaise sweet pickle relish ground black pepper salt smoked boneless ham 1 small onion 2 celery stalks Dice 2 to 4 lbs smoked boneless ham. Dice 2 stalks of celery and 1 small onion. Mix ham, celery and onion with 1 to 2 cups mayonnaise. Add 1/2 teaspoon of freshly ground black pepper and 1 1/2 teaspoons salt add more to taste. -

Mains Desserts

musubi apps & sides (cont.) each order is cut into three bite-sized pieces Iberico Pork Belly Skewers, miso-daikon-ginger seasoning - $10 Musubi Platter, choose four below* - $20 Spanish Octopus Skewers, five-spiced bacon, charred scallion - $9 SPAM, classic - $5 Vegetable Skewers, heirloom squash, shiitake mushroom, sumiso - $7 Spicy SPAM, soy-pickled jalapeños, soy mayo - $5 Skewer Tasting, tasting of three skewers - $12 Galbi, braised beef short rib, kimchi (contains shellfish) - $6 Assorted Pickles, rotating selection of house made pickles - $5 Pork Jowl, scallion and ginger purée - $6 Hawaiian Macaroni Salad, onions, carrots, celery, dairy - $5 Spicy Tuna Tataki, yuzu kosho, chili, sesame oil* - $6 Kimchi, traditional napa cabbage kimchi (contains shellfish) - $5 Shiitake Mushroom, kombu, ginger - $5 Kimchi, green beans, almonds, shiso (contains shellfish) - $6 Katsuobushi, braised bonito flakes, cucumber sunomono - $5 Kimchi, pea leaf, carrots, blood orange - $7 Spicy Salmon Tartare, tobiko mayo* - $6 Spicy Tuna Tartare, chili, sesame oil, shiso* - $6 Hokkaido Uni, braised kombu, shiso* - $28 / $23 supp. on platter mains Lobster, coral aioli, yuzu kosho* - $15 / $10 supp. on platter Teriyaki Chicken Bowl, asian greens, sesame, steamed rice - $15 Japanese Scallop, nori mayo, lemon* - $10 / $5 supp. on platter Garlic Shrimp Bowl, garlic & butter, pineapple, chili, steamed rice - $16 Miyazaki A5 Wagyu, soy-pickled garlic* - $15/ $10 supp. on platter Chow Noodle, spiced tofu, black bean and szechuan chili - $15 Luxury Musubi Trio, Hokkaido -

Pork Soy Base and Chicken Stock Pac Choi, Bamboo Shoot

pork 12 tofu 10 soy base and chicken stock (cold) yuzu dressing pac choi, bamboo shoot, mushroom, spring onion, egg rukkora, daikon, cherry tomatoes, mixed seeds seafood 15 vegetable tempura 11 salt base and seafood stock soy base and fish & kelp stock rukkora, bamboo shoot, mushroom, spring onion, egg carrot, onion, sweet potato, seaweed, lotus root, spring onion vegetable 11 soy base andvegetable stock rukkora, bamboo shoot, mushroom, pac choi, spring onion, egg vegetable 11 tofu 11 curry base andvegetable stock spicy miso base and vegetable stock lotus root, asparagus, aubergine, red pepper, onion pac choi, spring onion, chilli strings chicken 11 chicken 12 (cold) sesame dressing salt base and chicken stock rukkora, cucumber, cherry tomatoes pac choi, fried onion, spring onion beef 14 soy base andfish & kelp stock onion, egg, spring onion エクストラ extras bamboo shoots 0.5 / lotus crisps 1 / sweet potato crisps 1 / cured egg 2 / mushrooms 1 エクストラ extras bamboo shoots 0.5 / lotus crisps 1 / sweet potato crisps 1 / cured egg 2 / mushrooms 1 vegetables 1 / tofu 2 / noodles 2 / pork 3 / chicken 3 / prawn tempura 2pcs 4.5 vegetables 1 / tofu 2 / noodles 2 / pork 3 / chicken 3 / prawn tempura 2pcs 4.5 edemame 4 sea salt asahi 6 lager tap, pint pickles 4 daikon, cucumber, carrot kirin 6 malt tap, pint goma kyuri 4 cucumber, sesame, chilli sapporo 4.5 karaage 6 lager, bottle chicken prawn tempura 6 3 pcs calpis 3 junmai probiotic drink 7 standard grade, 100ml ramune 3 sparkling soda junmai ginjyo 9 juice 3 high grade, 100ml orange or apple, bottle 11 2 junmai daiginjyo sencha premium grade, 100ml green tea, cup 2 mugicha barley tea, cup ワイン wine house red 6 glass house white 6 glass plum wine soda 7 glass デザート dessert mochi ice balls 5 2pcs various flavours, please ask. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Network Admin\My Documents\Newsletter

From web site: www.about.com KGC Newsletter anese Fo ap od Issue 12, February 2003 J ByJoanne believe that most people are familiar with temperature for frying Tempura. Japanese food. When I first tasted it, it e. Using shrimp: Iwas wonderful. It looks small and cute, In order to make each shrimp stay straight, and it tastes good. If you eat it, you will want you can put a couple incisions into its to eat it again next time. Today, there are stomach. Then, pick up its tail and put the In This Issue many Japanese restaurants all around the body in the batter. world, and people can learn about Japanese f. Squid: food customs. Since I enjoy Japanese food so Before you dip it in Tempura batter, you much, I would like to introduce different should remove the shell and flour the shrimp kinds of Japanese food to everybody. lightly. Japanese Food 5) Japanese Sweets: 1) History of Sushi: Japanese sweets are called wa-gashi in It is said that sushi came from China in the 7th Japanese, and wa-gashi contains rice flour, red Winter Fun in Vancouver century. At the beginning, people used fresh beans and sugar. When you cook wa-gashi, fish to make sushi, but because there were no you can put in some batter and milk. Food in Chinese Culture refrigerators, people had to make it with salt So, many people like to eat Japanese sweets so that the sushi wouldn’t spoil. Since then, because it won`t make them fat. sushi has been combined with fish and salt. -

Small Plates Soups & Salads Noodle Bowls Congee

SMALL PLATES Edamame 6 Egg Rolls 9 Sweet Chili Sauce Pot Stickers 10 Soy vinegar dipping sauce Vegetable Spring Rolls 10 Sweet & Sour duck sauce Crab Rangoon 11 Spicy plum sauce BBQ Spare Ribs 13 Crispy Dynamite Shrimp 13 Spicy mayonnaise Shrimp Tempura 12 Mirin Dipping sauce Vegetable Tempura 10 Mirin Dipping sauce SOUPS & SALADS House Salad with Ginger Dressing 7 Mixed greens, onions, carrots, julienne tomatoes, daikon threads & Kaiware Marinated Seaweed Salad 7 Sliced cucumber, carrots, in a sesame soy ginger marinade Hot & Sour 7 Chicken broth, bamboo shoots, mushrooms, tofu, dark soy & egg Wonton 8 Shrimp & Pork dumpling with chicken broth and Chinese broccoli Miso 7 Tofu, seaweed, & scallions NOODLE BOWLS Egg Noodles, Chow Fun, or Rice Noodle Vietnamese Pho 15 Fish Balls, Beef Balls, Rare Beef or a Combination Braised Chicken Noodle 14 Shredded chicken, scallions with fresh ho fun Oxtail with Kim chee 14 Braised oxtail with carrots, ginger in beef broth Spicy Seafood Udon Noodle 16 Shrimp & scallops with Chinese broccoli Vegetable Noodle Soup 13 Thin egg noodles, fresh enoki mushrooms, snow peas, yu choy, bean sprouts, scallions & fried shallots CONGEE Rice Porridge Chicken, Beef or Pork 10 Seafood 14 275032 10 /13 SPECIALTY ROLLS Lillie’s Roll 14 Spicy Tuna wrapped inside out, topped with avocado and eel sauce Jersey Shore 16 Soft shell crab, cream cheese, salmon with basil aioli and eel sauce The Boardwalk 18 Crunchy soft shell crab, cucumber, topped with spicy tuna, crab mix and sweet soy The Nugget 18 Shrimp, scallops, Asian vegetables, tempura fried, with spicy ponzu dipping sauce Yum Yum Babe 18 Shrimp tempura, crab mix, cucumber, topped with spicy salmon, avocado with ponzu spicy mayo Dragon 16 Jumbo lump crab, cream cheese, cucumber, masago, inside out, topped with tuna and avocado Hand Grenade 14 Hand Roll scallops, shrimp, masago, tempura crunch Taste of A.C. -

Noriedgewatertogo2018-10.Pdf

Shoyu Ramen 12.95 Nori Appetizers Nori Salads Japanese Egg Noodles, Soy Sauce Pork Broth, Pork Chashu, Nori Kitchen Entrees Sushi Vegetable Maki Some of our dishes may contains sesame seeds and seaweed. Marinated Bamboo Shoots, Quail Eggs, Spinach, Japanese Served with Miso Soup, Salad and Rice (add $1 for spicy miso soup) Nigiri (Sliced fish on a bed of rice 1 pc/ order) Contains Sesame Seeds (add $1 for soy paper) Some of our dishes may contains sesame seeds and seaweed. Some of Our Maki Can Be Made in Hand Roll Style. Edamame 5.00 Mixed Greens Salad 6.00 Prepared Vegetables and Sesame Seeds. Topped with Green Sashimi (Sliced fish) (2 pcs./ order) add $2.00 Steamed Japanese Soy Bean, Sprinkled Lightly with Salt. Mixed Greens, Carrots, Cucumbers and Tomatoes. Served With Onion, Fish Cake and Seaweed Sheet. Shrimps & Vegetables Tempura Dinner 13.95 Ebi Avocado Maki Avocado. 4.00 Botan Ebi sweet shrimp with fried head 3.50 Nori Tempura (2 Shrimps 6 Vegetables)9.50 Japanese Style Ginger Dressing Or Creamy Homemade Dressing. Chicken Katsu Ramen 12.95 Deep Fried Shrimps and Vegetables Tempura Avocado Tempura Maki 6.00 Deep Fried Shrimps and Assorted Vegatables; Sunomono Moriawase (Japanese Seafood Salad) 9.00 Japanese Egg Noodles, Marinated Bamboo Shoots, Quail Eggs, with Tempura Sauce. Ebi boiled shrimp 2.50 Avocado tempura with spicy mayo. Crab meat, Ebi, Crab Stick, Tako, Seaweed and Cucumber A Quintessentially Japanese Appetizer. Spinach, Japanese Prepared Vegetables and Sesame Seeds. Chicken Katsu 13.95 Escolar super white tuna 3.50 Asparagus Maki Steamed asparagus. -

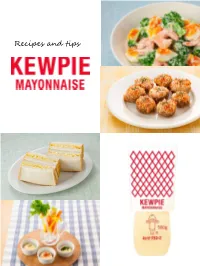

Recipes and Tips Shrimp and Egg Salad a Simple but Filling Salad That Is Quick and Easy to Prepare

Recipes and tips Shrimp and Egg Salad A simple but filling salad that is quick and easy to prepare. 2 servings 10minutes Ingredients Directions 1/2 head of Broccoli 1. Cut the broccoli into small florets. 3 Boiled eggs Heat water, add salt and boil broccoli. 2. Cut boiled egg into bite- size pieces. 6 Small boiled shrimp 3. Mix the broccoli, boiled egg, boiled Salt to taste shrimp together with KEWPIE KEWPIE Mayonnaise Mayonnaise. Baked Mushrooms with Mayonnaise Topped with aromatic garlic mayonnaise, these baked mushrooms make a great appetizer or party snack. 2 servings 15minutes Ingredients Directions 8 Mushrooms 1. Cut the stems off the mushrooms. 2 strips of Bacon 2. Cut bacon into 5 mm squares. Mix bacon with grated garlic and KEWPIE Minced Parsley (For garnish) Mayonnaise to make the filling. 1/2 tsp. grated Garlic 3. Put the filling into the mushroom and 3 tbsp. KEWPIE Mayonnaise place them on a lined oven safe tray. 4. Bake them at 240℃ for 8 minutes. 5. Sprinkle with minced parsley and serve. Japanese Egg Sandwiches This simple recipe requires no boiling. The egg filling is heated in the microwave and mixed with KEWPIE Mayonnaise. 2 servings 10minutes Ingredients Directions 4 slices of White Bread 1. Beat egg, add milk and salt and mix 3 Eggs well. 2. Heat in the microwave for 2 minutes 2 tbsp. Milk at 500W. Remove and mix lightly, then A pinch of Salt heat again for 1 minute. 2 tbsp. KEWPIE Mayonnaise 3. Allow to cool, add KEWPIE Mayonnaise and mix well. -

Enjoy Your Meal!

APPETIZERS MISO SOUP $1.95 EDAMAME $4.95 GREEN SALAD $3.95 SEAWEED SALAD $4.95 GYOZA (8pc) $5.95 EGG ROLLS (3pc) $5.95 FRIED SHRIMP (6pc) $6.95 COMBINATION TEMPURA $9.95 ( 2PC SHRIMP AND 9PC VEGETABLE ) POKE BOWL CRAB MEAT, AVOCADO, CUCUMBER, SPRING MIX SALAD, RICE, SEAWEED SALAD, SPICY MAYO AND GARLIC PONZ SAUCE TUNA POKE BOWL $12.95 SALMON POKE BOWL $12.95 BEVERAGES CAN SODA $1.50 BOTTLE SODA $2.50 CATERING We love to cater parties and events. You decide what you want on the tray! Not sure what you want? Monday - Satday Give us a call and we can help build your party tray 10:30AM - 10:00PM based on what you like. Contact us today and we’ll create a masterpiece for you. 1201 Dexter Ave N, Seattle, WA 98109 206) 282-2113 Enjoy your meal! Consumer Advisory : Consumption of undercooked meat, poultry, eggs or seafood may increase the risk of food-born illnesses. Alert your server if you have special dietary requirements. TERIYAKI SPECIAL SUSHI ROLLS SUSHI / SASHIMI COMBO SERVED WITH RICE AND SALAD RAINBOW ROLL $9.95 (FOUR KINDS OF FISH ON TOP OF CALIFORNIA ROLL) SUSHI COMBO $14.95 CHICKEN $9.95 (TUNA, SALMON, ALBACORE TUNA, YELLOW TAIL, WHITE FISH, SHRIMP AND DRAGON ROLL $9.95 CALIFORNIA ROLL) SPICY CHICKEN $10.95 (BROILED EEL OVER CALIFORNIA ROLL) SASHIMI COMBO $17.95 PORK $11.95 TIGER ROLL $10.95 ( 3 TUNA, 3 SALMON, 3 YELLOW TAIL AND 2 WHITE FISH ) (CRAB MEAT, CUCUMBER, AVOCADO TOPPED WITH COOK SHRIMP, CHICKEN BREAST $12.95 AND SPICY MAYO) BEEF $13.95 CATERPILLAR ROLL $11.95 (FRESH WATER EEL, CUCUMBER, TOPPED WITH AVOCADO AND SALMON $14.95 -

Pandemic Menu Front

Fresh Fish Roll Baked Roll (Any spicy roll has tempura bits in ) (Hand Roll) Crab Meat Roll (6pcs)................................................... 4.95 3.95 Bulgogi Roll (6pcs)........................................................................ 6.95 TASTETASTE OFOF REALREAL JAPANJAPAN Beef with cucumber Spicy Crab Meat Roll (6pcs)..................................... 5.95 4.95 Salmon Skin Roll (6pcs)............................................................. 6.95 Salmon Roll (6pcs).......................................................... 5.95 6.50 Baked salmon skin with cucumber Salmon with Avocado (6pcs)................................... 7.95 8.50 Unagi Roll (6pcs)............................................................................. 9.95 BBQ eel with cucumber Spicy Salmon Roll (6pcs)............................................ 6.95 5.95 Futo Roll(Thick roll) /Spicy Futo Roll .(10pcs) ............10.95......... ./11.95 Spicy Salmon with Avocado (6pcs)..................... 7.95 6.95 Crab, cucumber, radish, rolled egg, seasoned gourd Tuna Roll (6pcs)................................................................ 6.95 7.50 Hawaiian Roll (8pcs).................................................................... 12.95 Spicy salmon and red snapper on top - Baked roll Spicy Tuna Roll (6pcs)................................................. 7.95 6.95 Seattle Roll (8pcs)......................................................................... 12.95 Spicy Tuna with Avocado (6pcs).......................... 8.95 7.95 Salmon, cream -

Meiji Dinner Menu

Dessert Yuzu Pie 6 Meiji Dinner Menu Goat milk, lime, yuzu, graham cracker crust ‘v’ is for vegetarian, ‘v+’ is for vegan, ‘gf’ is for gluten free Whiskey & Cookies 7 15% Service Fee applied to all food and beverage Fresh-baked chocolate chip cookies with 1 oz Maker’s Mark Private we cannot accommodate menu substitutions or omissions Select: aged in a barrel selected by Izakaya Meiji Co. & Downtown Liquor, *consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish or -dairy free- eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illness Castella Cake 7 Portuguese honey cake, pickled strawberries, vanilla aquafaba ‘ice cream’ Kobachi (small plate) Miso Egg* V GF 3 Marinated soft-boiled egg Kimchi GF 4 House-made with napa cabbage Organic Miso Soup GF 4 Dashi broth, organic silken tofu, wakame, white miso Edamame V+ GF 4 Soybeans, red clay salt Rayu Edamame V+ GF 5 Soybeans, house-made rayu, garlic Japanese Potato Salad* V GF 5 Yukon gold potatoes, cucumber, soft-boiled egg, Kewpie mayo, yuzu kosho Cucumber Tsukemono V+ GF 5 Japanese pickles French Fries V GF 5 House-cut fries, wasabi mayonnaise* Wakame Salad GF 7 Blue Evolution wakame, carrot, daikon, cucumber, sesame, dashi, tamari Pork Gyoza 8 All-natural pork, napa cabbage, nira, sesame, 6 per order Steamed Rice V+ GF 3 Vegetable Fish Broccoli & Garlic V GF 5 Hot Garlic Shrimp GF 10 Organic broccoli, garlic, goat butter Fresno pepper, aquafaba butter, garlic, tamari, chili oil Shiitake Skewer V GF 5 Rockfish Kara-age GF 9 Miso goat butter Fried rockfish, tamari, sake, basil, ginger, ponzu -

Sushi Global«: Zwischen J-Branding Und Kulinarischem Nationalismus

»Sushi global«: Zwischen Jbranding und kulinarischem Nationalismus Sushi Gone Global: Between J-branding and Culinary Nationalism Dorothea Mladenova Based on a historical outline of how Sushi travelled from Japan via the U.S. to Europe with a special focus on Germany, it is argued that today there exist at least two forms of Sushi, the »original« and the »glocal«, both of which have their own history and legitimacy. By applying the globalization theories of Appadurai (2008), Ritzer (2008) and Ng (2001) it is shown how global Sushi emerged from Japanese Sushi while be- coming an independent item and hybridizing itself. Therefore, Sushi does not fit in the narrow framework of »national« or »ethnic« cuisine any more. The article states that by referring to global Sushi variations as »fake«, the Japanese agents who advocate a »clean-up« of the global sushi economy are ignoring that the two different types can- not be judged by the same standard, because they follow different rules and patterns of consumption and thereby serve different functions. 1. Einleitung Ist von »japanischem Essen« die Rede, so fällt zumeist auch sehr bald das Stichwort »Sushi«. Zwar spielt es in Japan selbst sowohl im häuslichen als auch im gastrono- mischen Bereich eine eher untergeordnete Rolle, da zum einen die Zubereitung von nigirizushi und makizushi als eine Meisterleistung angesehen wird, so dass man sich daheim nur an vereinfachte Varianten wie chirashizushi oder temakizushi1 1. Unter nigirizushi werden von der Hand geformte Reisquader mit einer Scheibe frischen Fischs verstanden. Mit makizushi ist in Algen gerolltes Sushi gemeint. Beim chirashizushi werden der 276 Gesellschaft traut, und zum anderen weil in der Gastronomie Sushi entweder als haute cuisine für besondere Anlässe oder als Familienspaß im Schnellrestaurant gilt, und auch dies erst seit der Rezession in den 1990er Jahren (Silva und Yamao 2006). -

The Hip Chick's Guide to Macrobiotics Audiobook Bonus: Recipes

1 The Hip Chick’s Guide to Macrobiotics Audiobook Bonus: Recipes and Other Delights Contents copyright 2009 Jessica Porter 2 DO A GOOD KITCHEN SET-UP There are some essentials you need in the kitchen in order to have macrobiotic cooking be easy and delicious. The essentials: • A sharp knife – eventually a heavy Japanese vegetable knife is best • Heavy pot with a heavy lid, enameled cast iron is best • Flame deflector or flame tamer, available at any cooking store • A stainless steel skillet • Wooden cutting board • Cast iron skillet Things you probably already have in your kitchen: • Blender • Strainer • Colander • Baking sheet • Slotted spoons • Wooden spoons • Mixing bowls • Steamer basket or bamboo steamer 3 You might as well chuck: • The microwave oven • Teflon and aluminum cookware Down the road: • Stainless-steel pressure cooker • Gas stove • Wooden rice paddles You know you’re really a macro when you own: • Sushi mats • Chopsticks • Suribachi with surikogi • Hand food mill • Juicer • Ohsawa pot • Nabe pot • Pickle press • A picture of George Ohsawa hanging in your kitchen! Stock your cupboard with: • A variety of grains • A variety of beans, dried • Canned organic beans • Dried sea vegetables • Whole wheat bread and pastry flour • A variety of noodles • Olive, corn, and sesame oil • Safflower oil for deep frying 4 • Shoyu, miso, sea salt • Umeboshi vinegar, brown rice vinegar • Mirin • Sweeteners: rice syrup, barley malt, maple syrup • Fresh tofu and dried tofu • Boxed silken tofu for sauces and creams • A variety of snacks from the health-food store • Tempeh • Whole wheat or spelt tortillas • Puffed rice • Crispy rice for Crispy Rice Treats • Organic apple juice • Amasake • Bottled carrot juice, but also carrots and a juicer • Agar agar • Kuzu • Frozen fruit for kanten in winter • Dried fruit • Roasted seeds and nuts • Raw vegetables to snack on • Homemade and good quality store- bought dips made of tofu, beans, etc.