Chapter 16 the Locative Applicative and the Semantics of Verb Class in Kinyarwanda Kyle Jerro University of Texas at Austin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marie-Neige Umurerwa

“For me, switching from one language to another is like switching from one music or rhythm to another, from one tone to another” Hello! My name is Marie-Neige Umurerwa. My family and I live in Lier (a city in the province of Antwerp). I am a Belgian-Rwandan French-speaking. I speak six languages: Kinyarwanda, French, Lingala, Kiswahili, English and Dutch. Thanks to my mother, I have had the opportunity to travel a lot and I lived in different countries. I came to Belgium at the age of 9. That is how I acquired my multilingualism. I have always loved learning languages. For me, switching from one language to another is like switching from one music or rhythm to another, from one tone to another. Depending on what you feel, depending on how you experience things at the moment. For me, language is a translation of emotions. The more languages we speak, the more opportunities we have to access the hearts and emotions of people. Learning one or more languages should be done spontaneously and with pleasure, like a game. The sooner we start learning languages as a child, the more effective it will be. Rwanda has four official languages, and everyone is able to speak more than one language. In a discussion, people easily switch from one language to another. We switch from English to French or from Kinyarwanda to Swahili. After a visit to my home country, I went to a restaurant with my family. The waiter came to take our order. When it was my turn, my eyes were fixed on the menu and without even realizing it I place my order in Kinyarwanda! Of course, my family laughed and when I looked up, I saw the waiter - in shock - asked me; "Excuseer Mevrouw, ik heb niks begrepen, wat zei u?” This situation happens to me often. -

1 Parameters of Morpho-Syntactic Variation

This paper appeared in: Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 105:3 (2007) 253–338. Please always use the published version for citation. PARAMETERS OF MORPHO-SYNTACTIC VARIATION IN BANTU* a b c By LUTZ MARTEN , NANCY C. KULA AND NHLANHLA THWALA a School of Oriental and African Studies, b University of Leiden and School of Oriental and African Studies, c University of the Witwatersrand and School of Oriental and African Studies ABSTRACT Bantu languages are fairly uniform in terms of broad typological parameters. However, they have been noted to display a high degree or more fine-grained morpho-syntactic micro-variation. In this paper we develop a systematic approach to the study of morpho-syntactic variation in Bantu by developing 19 parameters which serve as the basis for cross-linguistic comparison and which we use for comparing ten south-eastern Bantu languages. We address conceptual issues involved in studying morpho-syntax along parametric lines and show how the data we have can be used for the quantitative study of language comparison. Although the work reported is a case study in need of expansion, we will show that it nevertheless produces relevant results. 1. INTRODUCTION Early studies of morphological and syntactic linguistic variation were mostly aimed at providing broad parameters according to which the languages of the world differ. The classification of languages into ‘inflectional’, ‘agglutinating’, and ‘isolating’ morphological types, originating from the work of Humboldt (1836), is a well-known example of this approach. Subsequent studies in linguistic typology, e.g. work following Greenberg (1963), similarly tried to formulate variables which could be applied to any language and which would classify languages into a number of different types. -

Name Language E-Mail Phone City French Swahili Lingala Hemba Kiluba Kirundi Kinyarwanda Swahili French French Swahili Lingala 4

Name Language E-mail Phone City French Swahili 1 Beatrice Mbayo Lingala [email protected] 859 -457 -7205 Lexington Hemba Kiluba Kirundi Kinyarwanda 2 Brigitte Nduwimana [email protected] 859-913-1419 Lexington Swahili French French 3 Christine Yohali Swahili [email protected] 859-368-2276 Lexington Lingala 4 Durar Shakir Arabic [email protected] 618-924-0629 Lexington Kinyarwanda 5 Lodrigue Mutabazi [email protected] 615-568-1689 Lexington Swahili Swahili 6 Modest M Bittock Kinyarwanda [email protected] (859)285-3740 Lexington Kirundi 7 Ranuka Chettri Nepali [email protected] 859-312-8216 Lexington 8 Shaza Awad Arabic [email protected] 606-215-9571 Lexington Kirundi Kinyarwanda 9 Tite Niyonizigiye [email protected] 859-368-3167 Lexington Swahili French Somali 10 Abdirizak Mohamed [email protected] 502-450-1346 Louisville Mai-Mai Dari Farsi Urdu Persian 11 Abdul Hasib Abdul Rasool [email protected] 502-337-4550 Louisville Hindi Russian Ukrainian Pashto Somali Swahili 12 Amina Mahamud [email protected] 207-415-5118 Louisville Mai Mai Hindi Dari Persian 13 Aneela Abdul Rasool Farsi [email protected] 502-337-5587 Louisville Urdu Hindi Nepali 14 Buddha Subedi [email protected] 502-294-1246 Louisville Hindi 15 Chandra Regmi Nepali [email protected] 502-337-5524 Louisville Kinyarwanda Swahili 16 Chantal Nyirinkwaya French [email protected] 502-299-4169 Louisville Kirundi Lingala Burmese 17 Hnem Kim [email protected] 502-298-4321 Louisville Chin Kinyarwanda 18 Jean de Dieu Nzeyimana Kirundi -

Southern Africa As a Phonological Area

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology/Linguistics "Speaking (of) Khoisan" A symposium reviewing African prehistory 16/05/2015 Southern Africa as a phonological area Christfried Naumann & Hans-Jörg Bibiko [email protected] Quelle: Clements & Rialland ( 2008 : 37 ) Contents 1. Introduction 3-15 2. Procedure 16-19 3. Results: Kalahari Basin 20-28 4. Results: Southeastern Bantu 29-42 5. Results: Southern Africa 43-54 (6. Local and dependent features - excluded) 55-61 7. MDS and k-means 62-68 8. Summary 69 (9. Contact scenarios) 70-74 Acknowledgements 75 References 76-77 2 "Speaking (of) Khoisan", 16/05/2015 Southern Africa as a phonological area 1. Introduction Phonological similarities • large consonantal inventory (45 c.) • clicks • aspirated and ejective stops • dorsal affricate 3 "Speaking (of) Khoisan", 16/05/2015 Southern Africa as a phonological area 1. Introduction Phonological similarities • large consonantal inventory (50 c.) • clicks • aspirated, slack voiced, ejective and imploisve stops •(dorsal affricate) lateral obstruents • 4 "Speaking (of) Khoisan", 16/05/2015 Southern Africa as a phonological area 1. Introduction Phonological similarities • large consonantal inventory (68 c.) • (clicks) • aspirated, breathy and implosive stops • lateral obstruents 5 "Speaking (of) Khoisan", 16/05/2015 Southern Africa as a phonological area 1. Introduction Example: Distribution of ejectives/glottalized consonants Clements & Rialland (2008: 62) Maddieson (2013) 6 "Speaking (of) Khoisan", 16/05/2015 Southern Africa -

Syntactic and Phonological Phrasing in Bemba Relatives

Syntactic and phonological phrasing in Bemba Relatives Lisa Cheng Leiden University Nancy C. Kula Leiden University (LUCL) Tone as a distinctive feature used to differentiate not only words but also clause types, is a characteristic feature of Bantu languages. In this paper we show that Bemba relatives can be marked with a low tone in place of a segmental relative marker. This low tone strategy of relativization, which imposes a restrictive reading of relatives, manifests a specific phonological phrasing that can be differentiated from that of non-restrictives. The paper shows that the resultant phonological phrasing favours a head-raising analysis of relativization. In this sense, phonology can be shown to inform syntactic analyses. 1 Introduction Relative clauses in Bantu have been a part of continued research dating back to Meeussen (1971). Various typologies and analyses that aim to capture the dependencies expressed in this clause type have been proposed (Givón 1972, Nsuka 1982, Walusimbi 1996). Despite the fact that there is overwhelming evidence of relative clauses formed by tone in various Bantu languages (Luganda, Kinyarwanda, Nsenga, Chichewa, Umbundu, Luba) hardly any analyses try to associate this fact to the syntactic analyses and generalisations proposed, but see Kamwangamalu (1988) for Luba. This paper investigates (syntactic) analyses of relative clauses in Bantu, with particular reference to Bemba, that take recourse to phonological phrasing. We begin by outlining the strategies for relative clause formation in Bemba in section 2 for both subject and object relatives. In section 3 we look at the limitations of the tonal marking strategy as opposed to relatives marked with segmental relative markers. -

Low-Density Language Selection: Kinyarwanda and Malagasy

Low-density language selection: Kinyarwanda and Malagasy Jason Baldridge Wednesday, October 27, 2010 Low-density languages Languages discussed in the proposal: Encompasses a wide range of typologically diverse, primarily African, languages. We propose to work on Kinyarwanda and Malagasy © 2010 Jason M Baldridge 2 MURI Kickoff, October 2010 Wednesday, October 27, 2010 Why Kinyarwanda and Malagasy Two families, with many related languages: Kinyarwanda: Niger-Congo / Bantu Malagasy: Austronesian / Malayo-Polynesian Both connected to Swahili (Kinyarwanda: genetic, Malagasy: uses Swahili loan words) Both well studied in the linguistics literature: access to expertise and informants Access to monolingual data. Together, they cover all the major linguistic issues discussed in the proposal, namely morphology, word order, grammatical categories, voice systems, serial verbs, and more. © 2010 Jason M Baldridge 3 MURI Kickoff, October 2010 Wednesday, October 27, 2010 Kinyarwanda Niger-Congo family, Bantu sub- family Spoken in Rwanda (official language), Uganda, DR Congo. Est. 7.5 million speakers in Rwanda, 20+ million overall © 2010 Jason M Baldridge 4 MURI Kickoff, October 2010 Wednesday, October 27, 2010 Kinyarwanda data sources in hand Monolingual texts available online Sites, e.g. www.izuba.org.rw Kinyarwanda Wikipedia (111 articles) Access to experts and native speakers through UT Austin Extensive linguistics literature (especially Kimenyi 1980) Kigali Memorial Centre 200 survivor testimonies of the Rwandan genocide: Kinyarwanda, English, and French 340 transcripts from Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines. © 2010 Jason M Baldridge 5 MURI Kickoff, October 2010 Wednesday, October 27, 2010 Human Rights Documentation Initiative http://www.lib.utexas.edu/hrdi/ © 2010 Jason M Baldridge 6 MURI Kickoff, October 2010 Wednesday, October 27, 2010 Complex morphology Concatenative morphology: word formation adds many affixes to verb roots to indicate subjects and objects and to mark agreement, tense, aspect, mood, and shifts in meaning. -

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE

Language Information LANGUAGE LINE. The Court strongly prefers to use live interpreters in the courtrooms whenever possible. However, when the Court can’t find live interpreters, we sometimes use Language Line, a national telephone service supplying interpreters for most languages on the planet almost immediately. The number for that service is 1-800-874-9426. Contact Circuit Administration at 605-367-5920 for the Court’s account number and authorization codes. AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE/DEAF INTERPRETATION Minnehaha County in the 2nd Judicial Circuit uses a combination of local, highly credentialed ASL/Deaf interpretation providers including Communication Services for the Deaf (CSD), Interpreter Services Inc. (ISI), and highly qualified freelancers for the courts in Sioux Falls, Minnehaha County, and Canton, Lincoln County. We are also happy to make court video units available to any other courts to access these interpreters from Sioux Falls (although many providers have their own video units now). The State of South Dakota has also adopted certification requirements for ASL/deaf interpretation “in a legal setting” in 2006. The following link published by the State Department of Human Services/ Division of Rehabilitative Services lists all the certified interpreters in South Dakota and their certification levels, and provides a lot of other information on deaf interpretation requirements and services in South Dakota. DHS Deaf Services AFRICAN DIALECTS A number of the residents of the 2nd Judicial Circuit speak relatively obscure African dialects. For court staff, attorneys, and the public, this list may be of some assistance in confirming the spelling and country of origin of some of those rare African dialects. -

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages Gerrit J. Dimmendaal University of Cologne John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American 8 National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dimmendaal, Gerrit Jan. Historical linguistics and the comparative study of African languages / Gerrit J. Dimmendaal. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. African languages--Grammar, Comparative. 2. Historical linguistics. I. Title. PL8008.D56 2011 496--dc22 2011002759 isbn 978 90 272 1178 1 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 1179 8 (Pb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 8722 9 (Eb) © 2011 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Company • P.O. Box 36224 • 1020 me Amsterdam • The Netherlands John Benjamins North America • P.O. Box 27519 • Philadelphia PA 19118-0519 • USA UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Table of contents Preface ix Figures xiii Maps xv Tables -

Lunyole Grammar; It Does Not Attempt to Make a Statement for Or Against a Particular Formal Linguistic Theory

A PARTIAL GRAMMAR SKETCH OF LUNYOLE WITH EMPHASIS ON THE APPLICATIVE CONSTRUCTION(S) _______________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Intercultural Studies Department of Applied Linguistics & TESOL Biola University _______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics _______________________ by Douglas Allen Wicks May 2006 ABSTRACT A PARTIAL GRAMMAR SKETCH OF LUNYOLE WITH EMPHASIS ON THE APPLICATIVE CONSTRUCTION(S) Douglas Allen Wicks This thesis provides a general grammatical description of Lunyole, a Bantu language of Eastern Uganda. After a brief description of the phonology, it describes the morphology and basic syntax of Lunyole, following Payne’s (1997) functional approach. This thesis then more deeply describes Lunyole’s applicative constructions in which an argument is added to the verb complex. Lunyole has two applicative marking constructions. The more productive one uses the -ir suffix on verbs of any valence in conjunction with a wide range of semantic roles. The other applicative construction is formed from a locative class prefix and is used only for locative arguments on unaccusative intransitive verbs. Similar locative morphemes may co-occur with the -ir applicative morpheme, but not as applicative markers; instead they clarify the relationship between arguments. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... ix List of Figures......................................................................................................................x -

A Phonological Analysis of Lwidakho Loanwords from Kiswahili and English

A PHONOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF LWIDAKHO LOANWORDS FROM KISWAHILI AND ENGLISH BY MORAND SHIKHOVA SHIDIAVAI C50/69747/2013 A Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Linguistics and Languages, University of Nairobi. November, 2015 i DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been submitted for the purpose of the award of a degree in any other University. Signature _________________________ Date: ________________ MORAND SHIKHOVA SHIDIAVAI This thesis has been submitted for examination with our approval as university supervisors. Signature _________________________ Date: ________________ DR. JANE AKINYI ODUOR NGALA Signature _________________________ Date: ________________ DR. HANAH CHAGA MWALIWA AKANGA ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to; My beloved late sister, Linnet Ingado My wonderful parents, Michael Ambenje and Christine Mideva My lovely sisters, Pauline Khasungu, Lucy Aleyo and Euslyne Indeche My dearest niece, Maclean Malavi and My best friend, Monica Wawuda iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I wish to proclaim my sincere gratitude to the Almighty God for the gift of life, good health, and innumerable favours. Thank you for the guidance, protection, and motivation throughout my studies. Secondly, I will forever remain greatly indebted to my alma mater; University of Nairobi. Thank you for easing my academic journey through your award of the prestigious University of Nairobi Scholarship. This indeed confirms that you are a world-class University committed to scholarly excellence. Thirdly, I wish to appreciate my supervisors: Dr. Jane Oduor and Dr. Hanah Mwaliwa. Your input into the present study is indispensable. Thank you so much for your patience, time and direction which added impetus to my research. -

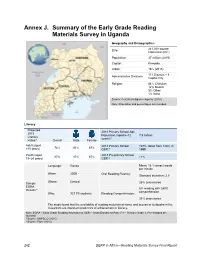

Annex J. Summary of the Early Grade Reading Materials Survey in Uganda

Annex J. Summary of the Early Grade Reading Materials Survey in Uganda Geography and Demographics 241,038 square Size: kilometers (km2) Population: 37 million (2015) Capital: Kampala Urban: 16% (2015) 111 Districts + 1 Administrative Divisions Capital City Religion 84% Christian 12% Muslim 3% Other 1% None Source: Central Intelligence Agency (2015). Note: Population and percentages are rounded. Literacy Projected 2013 Primary School Age 2015 Population (aged 6–12 7.9 million Literacy a a years): Rates: Overall Male Female Adult (aged 2013 Primary School 107%, down from 128% in >15 years) 74% 81% 67% a GER: 1999 Youth (aged 2013 Pre-primary School 87% 87% 87% 11% 15–24 years) GER:a Language: Ganda Mean: 18.1 correct words per minute When: 2009 Oral Reading Fluency: Standard deviation: 2.5 Where: Central Sample 26% zero scores EGRA 6% reading with ≥80% Results b comprehension Who: 927 P3 students Reading Comprehension: 38% zero scores The study found that the availability of reading materials at home and access to textbooks in the classroom are important predictors of achievement in literacy. Note: EGRA = Early Grade Reading Assessment; GER = Gross Enrollment Rate; P3 = Primary Grade 3. Percentages are rounded. a Source: UNESCO (2015). b Source: Piper (2010). 242 DERP in Africa—Reading Materials Survey Final Report Language Number of Living Languages a: 41 Major Languagesb Estimated Populationc Government Recognized Status English 2.5 million (L2) (2003) “Official”d language 313,000 (L1) (2015) Kiswahili “Official”f language 33.8 million (L2) (2015) 4.1 million (L1) (2002) Ganda (i.e., Luganda) LWC 1 million (L2) (1999) Acholi, Chiga, Lango, Masaaba, 1.1–2.3 million (L1) (2002) Nyankore, Soga, and Teso Adhola, Alur, Konzo, Kumam, Lugbara, Ng’akarimojong, Nyoro, 69,000–797,000 (L1) (2002-2004) Pokoot, and Talinga-Bwisi Note: L1 = first language; L2 = second language; LWC = language of wider communication. -

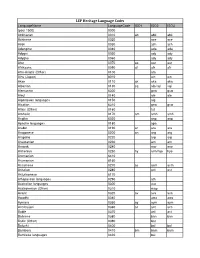

LEP Heritage Language Codes

LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 (post 1500) 0000 Abkhazian 0010 ab abk abk Achinese 0020 ace ace Acoli 0030 ach ach Adangme 0040 ada ada Adygei 0050 ady ady Adyghe 0060 ady ady Afar 0070 aa aar aar Afrikaans 0090 af afr afr Afro-Asiatic (Other) 0100 afa Ainu (Japan) 6010 ain ain Akan 0110 ak aka aka Albanian 0130 sq alb/sqi sqi Alemannic 6300 gsw gsw Aleut 0140 ale ale Algonquian languages 0150 alg Alsatian 6310 gsw gsw Altaic (Other) 0160 tut Amharic 0170 am amh amh Angika 6020 anp anp Apache languages 0180 apa Arabic 0190 ar ara ara Aragonese 0200 an arg arg Arapaho 0220 arp arp Araucanian 0230 arn arn Arawak 0240 arw arw Armenian 0250 hy arm/hye hye Aromanian 6410 Arumanian 6160 Assamese 0270 as asm asm Asturian 0280 ast ast Asturleonese 6170 Athapascan languages 0290 ath Australian languages 0300 aus Austronesian (Other) 0310 map Avaric 0320 av ava ava Awadhi 0340 awa awa Aymara 0350 ay aym aym Azerbaijani 0360 az aze aze Bable 0370 ast ast Balinese 0380 ban ban Baltic (Other) 0390 bat Baluchi 0400 bal bal Bambara 0410 bm bam bam Bamileke languages 0420 bai LEP Heritage Language Codes LanguageName LanguageCode ISO1 ISO2 ISO3 Banda 0430 bad Bantu (Other) 0440 bnt Basa 0450 bas bas Bashkir 0460 ba bak bak Basque 0470 eu baq/eus eus Batak (Indonesia) 0480 btk Bedawiyet 6180 bej bej Beja 0490 bej bej Belarusian 0500 be bel bel Bemba 0510 bem bem Bengali; ben 0520 bn ben ben Berber (Other) 0530 ber Bhojpuri 0540 bho bho Bihari 0550 bh bih Bikol 0560 bik bik Bilin 0570 byn byn Bini 0580 bin bin Bislama