Wula Nafaa Ii Local Governance Component Observations and Opportunities Volume 1: Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Livelihood Zone Descriptions

Government of Senegal COMPREHENSIVE FOOD SECURITY AND VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS (CFSVA) Livelihood Zone Descriptions WFP/FAO/SE-CNSA/CSE/FEWS NET Introduction The WFP, FAO, CSE (Centre de Suivi Ecologique), SE/CNSA (Commissariat National à la Sécurité Alimentaire) and FEWS NET conducted a zoning exercise with the goal of defining zones with fairly homogenous livelihoods in order to better monitor vulnerability and early warning indicators. This exercise led to the development of a Livelihood Zone Map, showing zones within which people share broadly the same pattern of livelihood and means of subsistence. These zones are characterized by the following three factors, which influence household food consumption and are integral to analyzing vulnerability: 1) Geography – natural (topography, altitude, soil, climate, vegetation, waterways, etc.) and infrastructure (roads, railroads, telecommunications, etc.) 2) Production – agricultural, agro-pastoral, pastoral, and cash crop systems, based on local labor, hunter-gatherers, etc. 3) Market access/trade – ability to trade, sell goods and services, and find employment. Key factors include demand, the effectiveness of marketing systems, and the existence of basic infrastructure. Methodology The zoning exercise consisted of three important steps: 1) Document review and compilation of secondary data to constitute a working base and triangulate information 2) Consultations with national-level contacts to draft initial livelihood zone maps and descriptions 3) Consultations with contacts during workshops in each region to revise maps and descriptions. 1. Consolidating secondary data Work with national- and regional-level contacts was facilitated by a document review and compilation of secondary data on aspects of topography, production systems/land use, land and vegetation, and population density. -

1 Project Title: «Strengthening Rural Women's Livelihood for A

Project Title: «Strengthening rural women’s livelihood for a sustainable economic development in the Eastern region of Senegal» Project Symbol: GCP/SEN/069/GAF Recipient country: Senegal Government/Other counterparts: Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Equipment (MAER) Expected EOD (Starting Date): 10th of January 2018 Expected NTE (End date): 1st of March 2021 Contribution to FAO’s strategic • The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Framework: Strategic Objectives (SO)/Priorities: The project will contribute to the following Strategic Objectives (SO), Outcomes, and Products: SO2: Make agriculture, forestry and fisheries more productive and sustainable. Outcome 201 – Producers and natural resources’ administrators adopt practices that increase and improve agricultural production in a sustainable way. Product 20101- Innovative methods are managed, tested, and disseminated by producers to increase, in a sustainable manner, productivity and production in order to curtail environmental degradation and climate change. SO4: Enable inclusive and efficient agricultural and food systems. Outcome 402 – The private and public sector strengthens the efficiency and inclusion of the agricultural value chain, specifically agribusinesses and agro-food chains. Product 40203 – Agribusiness and agro-food stakeholders receive technical support at the management level in order to promote the inclusiveness, efficiency and sustainability of the agro-food chains. Outcome 403 – Public-private policies, improved financial instruments, and increased -

Limiting Maize (Zea Mays L.) Yield in Two Agro-Ecological Zones of the Southern-Central of Senegal

JCBPS; Section B; February 2021 –April 2021, Vol. 11, No. 2; 396-406, E- ISSN: 2249 –1929 [DOI: 10.24214/jcbps.B.11.2.39606.] Journal of Chemical, Biological and Physical Sciences An International Peer Review E-3 Journal of Sciences Available online atwww.jcbsc.org Section B: Biological Sciences CODEN (USA): JCBPAT Research Article Evaluation of nutrients (N, P, K) limiting maize (Zea mays L.) yield in two agro-ecological zones of the southern-central of Senegal. Arona Sonko1,2*, Ndèye Yacine Badiane Ndour2, Moussa N’Diénor2, Aliou Faye3, Niokhor Bakhoum4 & Saliou Ndiaye1 1 Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Agriculture, Université Iba Der Thiam de Thiès, B.P A296 - Thiès – Sénégal. 2 Laboratoire National de Recherches sur les Productions Végétales, Institut Sénégalais de Recherches Agricoles, Bel Air, Route des Hydrocarbures, BP 3120 - Dakar - Sénégal. 3 Centre National de Recherches Agronomiques de Bambey, Institut Sénégalais de Recherches Agricoles, BP 53 CNRA – Bambey - Sénégal. 4 LMI LAPSE, Laboratoire Commun de Microbiologie IRD/ISRA/UCAD, Centre de Recherche de Bel Air, BP 1386, CP 18524 – Dakar - Sénégal. Received: 24 February 2021; Revised: 17 March 2021; Accepted: 30 March 2021 Abstract: Cereals response to nutrients varies according to soil characteristics in sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, subtractive trials were conducted to identify the major nutrients (N, P, K) limiting maize yield in Senegal central south (Nioro site) and east (Sinthiou Malème site) soils. In each zone, we set up a randomized complete block experiment on station with 4 replicates and on farm in 5 scattered fields. The following treatments were evaluated: non-fertilizer (T) control, completely fertilized with NPK at high doses (150N-40P2O5-40K2O kg/ha), and three other treatments (PK, NK, NP) resulting from the successive omission of one element from the NPK. -

USAID Wula Nafaa Project QUARTERLY REPORT

USAID Wula Nafaa Project QUARTERLY REPORT JANUARY – MARCH 2012 April 2012 This publication was produced for the United States Agency for International Development by International Resources Group (IRG). USAID Wula Nafaa Project QUARTERLY REPORT JANUARY - MARCH 2012 CONTRACT NO. 685-C-00-08-00063-00 Notice: The points of view expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or of the Government of the USA. Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................. III 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................... 2 3. PROGRESS ACHIEVED DURING THE QUARTER ............................................................. 5 3.1. Agriculture: Productivity and markets ....................................................... 5 3.1.1. Millet/sorghum and maize value chains ..................................................................... 5 3.1.2. Rice value chains ............................................................................................................. 9 3.1.3. Fisheries products ....................................................................................................... 11 3.1.4. Forest and agroforestry products .......................................................................... -

Mapping and Remote Sensing of the Resources of the Republic of Senegal

MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING OF THE RESOURCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL A STUDY OF THE GEOLOGY, HYDROLOGY, SOILS, VEGETATION AND LAND USE POTENTIAL SDSU-RSI-86-O 1 -Al DIRECTION DE __ Agency for International REMOTE SENSING INSTITUTE L'AMENAGEMENT Development DU TERRITOIRE ..i..... MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING OF THE RESOURCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL A STUDY OF THE GEOLOGY, HYDROLOGY, SOILS, VEGETATION AND LAND USE POTENTIAL For THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL LE MINISTERE DE L'INTERIEUP SECRETARIAT D'ETAT A LA DECENTRALISATION Prepared by THE REMOTE SENSING INSTITUTE SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY BROOKINGS, SOUTH DAKOTA 57007, USA Project Director - Victor I. Myers Chief of Party - Andrew S. Stancioff Authors Geology and Hydrology - Andrew Stancioff Soils/Land Capability - Marc Staljanssens Vegetation/Land Use - Gray Tappan Under Contract To THE UNITED STATED AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT MAPPING AND REMOTE SENSING PROJECT CONTRACT N0 -AID/afr-685-0233-C-00-2013-00 Cover Photographs Top Left: A pasture among baobabs on the Bargny Plateau. Top Right: Rice fields and swamp priairesof Basse Casamance. Bottom Left: A portion of a Landsat image of Basse Casamance taken on February 21, 1973 (dry season). Bottom Right: A low altitude, oblique aerial photograph of a series of niayes northeast of Fas Boye. Altitude: 700 m; Date: April 27, 1984. PREFACE Science's only hope of escaping a Tower of Babel calamity is the preparationfrom time to time of works which sumarize and which popularize the endless series of disconnected technical contributions. Carl L. Hubbs 1935 This report contains the results of a 1982-1985 survey of the resources of Senegal for the National Plan for Land Use and Development. -

IMPORTANT You Must Read the Following Before Continuing. The

IMPORTANT You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the Prospectus following this page, and you are therefore required to read this carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the Prospectus. In accessing the Prospectus, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them any time you receive any information from us as a result of such access. THE FOLLOWING PROSPECTUS MAY NOT BE FORWARDED OR DISTRIBUTED OTHER THAN AS PROVIDED BELOW AND MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED IN ANY MANNER WHATSOEVER. THIS PROSPECTUS MAY ONLY BE DISTRIBUTED OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES AND WITHIN THE UNITED STATES TO “QUALIFIED INSTITUTIONAL BUYERS” (QIBs) AS DEFINED IN AND PURSUANT TO RULE 144A OF THE U.S. SECURITIES ACT OF 1933, AS AMENDED (THE SECURITIES ACT) (RULE 144A). ANY FORWARDING, DISTRIBUTION OR REPRODUCTION OF THIS DOCUMENT IN WHOLE OR IN PART IS UNAUTHORISED. FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH THIS DIRECTIVE MAY RESULT IN A VIOLATION OF THE SECURITIES ACT OR THE APPLICABLE LAWS OF OTHER JURISDICTIONS. IF YOU HAVE GAINED ACCESS TO THIS TRANSMISSION CONTRARY TO ANY OF THE FOREGOING RESTRICTIONS, YOU ARE NOT AUTHORISED AND WILL NOT BE ABLE TO PURCHASE ANY OF THE NOTES DESCRIBED IN THE ATTACHED DOCUMENT. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER TO SELL OR THE SOLICITATION OF AN OFFER TO BUY ANY SECURITIES IN ANY JURISDICTION. THE SECURITIES HAVE NOT BEEN AND WILL NOT BE REGISTERED UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OR WITH ANY SECURITIES REGULATORY AUTHORITY OF ANY STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF THE UNITED STATES AND MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD WITHIN THE UNITED STATES EXCEPT TO QIBs PURSUANT TO RULE 144A. -

An Integrated Development Strategy for the Apiculture Industry Between Senegal, the Gambia and Guinea Bissau?

AN INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY FOR THE APICULTURE INDUSTRY BETWEEN SENEGAL, THE GAMBIA AND GUINEA BISSAU? ARTICULARLY FAVOURABLE CLIMATIC AND BOTANICAL CONDITIONS The Bissau Guinean sector in the restructuring process P Guinea Bissau has extraordinary potential for apiculture, especially Apiculture in Sénégambie méridionale (the Gambia, in the north east region (Gabu), with marshland inundated with Casamance, northern Guinea Bissau) relies on the planted mangroves covering an area of approximately favourable and homogeneous eco-geographic potential. 800,000 hectares, forest coverage of an estimated 1.5 million It is developing along a wide band comprising hectares and a population of which the majority earns their Casamance (Senegal) and inclusive of an area livelihood from agricultural activities and picked products. In 1987, between the southern axis which passes through the the Apiculture Association produced around 80,7083 kg of refined regions, from East to West, of Gabu, Oio and Cacheu honey as well as a little more than 10 tonnes of refined wax (Guinea Bissau) and a northern axis from east to west (ASTECAP – SNV). At the beginning of the 1990s, there were of the Gambia and the western border of the 22,352 traditional hives in the northern part and 93,464 in the Tambacounda Department (east Senegal) going back southern part of the country. up eastward towards the Kaffrine Department (Kolda region of Senegal). Despite economic liberalisation set in motion in 1986, continual politico-military crises since the beginning of the 1990s has led to a The Sudano-Guinean climate enables the development noteworthy reduction of the activity which resulted in an overt of tremendously diverse forestial growth, particularly decline in honey exports. -

The Wolof of Saloum: Social Structure and Rural Development in Senegal Stellingen

The Wolof of Saloum: social structure and rural development in Senegal Stellingen 1. Ein van de voorwaarden voor succesvolle toepassing van ossetrekkracht in de landbouw is een passende bedrijfsgrootte. In vele samenlevingen in West-Afrika wordt aan deze voor- waarde niet voldaan, omdat de leden van de huishoudgroep niet gezamenlijk, maar afzonder- lijk een bedrijf beheren. Dit proefschrift. 2. De conclusie dat in niet-westerse gebieden de positie van de vrouw verslechtert door opname in de marktecanomie en modernisering van de landbouw, is niet van toepassing op de Wolof-samenleving. Door de verbouw van handelsgewassen werd haar rol in de landbouw be- langrijker en nam haar inkomen toe. De recente toepassing van dierlijke trekkracht ver- lichtte haar taak op haar eigen veld. Postel-Coster, E. & J. Schrijvers, 1976. Vrouwen op weg; ontwikkeling naar emanci- patie. Van Gorcum, Assen. Dit proefschrift. 3. Moore verklaart de deelname aan werkgroepen met een maaltijd als beloning ('festive labour') mede uit de afhankelijkheid van de deelnemers ten opzichte van de begunstigde. Hierbij wordt over het hoofd gezien dat het voorkomt dat slechts een persoon deelneemt vanwege zijn afhankelijkheid van de begunstigde en dat deze persoon de overige deelnemers rekruteert volgens de regels van reciprociteit. Moore, M.P., 1975. Co-operative labour in peasant agriculture. Journal of Peasant Studies 2(3): 270-291. Dit proefschrift. 4. De gebruikelijke definitie van een marabout als zijnde een heilige en religieus leider met erg veel invloed is niet van toepassing op de Wolof, omdat hier vele marabouts slechts lokale bekendheid genieten. Dit proefschrift. 5. Er wordt vaak geen rekening gehouden met het feit dat de materiele positie van de kleine boer in ontwikkelingslanden niet alleen bepaald wordt door zijn activiteit als pro- ducent, maar tevens door zijn activiteit als handelaar. -

R4 Rural Resilience Initiative Annual Report January - December Contents

R4 Rural Resilience Initiative annual report January - December Contents Executive Summary 1 The R4 Model of Managing Risk 3 Project Status Summary 5 Key Accomplishments 9 Monitoring and Evaluation 2012 13 Financial Transaction Result s 2012 (Ethiopia) 16 Risk Reduction Results 2012 (Ethiopia) 21 Challenges and Lessons Learned 24 R4 Senegal Pilot Roll-out Plan 27 R4 Policy Engagement Plan 34 Financial Progress 35 Conclusion 36 Appendix I: Partners and Institutional Roles 37 Appendix II: Payout in Ethiopia Press Release, December 2012 38 Appendix III: Media Citations & Resources 40 Appendix IV: Rural Resilience Event Series 43 Appendix V: Summary of Transacted Index 2012 (Ethiopia) 47 Cover: Women are planting seedlings in Tigray, Ethiopia. Eva-Lotta Jansson / Oxfam America Woman participating in a small women’s savings group in her village in Koussanar, Senegal as part of Oxfam’s Saving for Change program. R4 will work with these groups for the savings and credit components. Katie Naeve / Oxfam America Executive Summary For the 1.3 billion people living on less than a dollar a day who partners, launched what is now called the R4 Rural Resilience depend on agriculture for their livelihoods, vulnerability to Ini8a8ve, known as R4, referring to the four risk management weather and climate-related shocks is a constant threat to food strategies that the ini8a8ve integrates. Ini8ated in 2010, R4 builds security and well-being. As climate change drives an increase in on the ini8al success of HARITA (Horn of Africa Risk Transfer for the frequency and intensity of natural hazards, the challenges Adapta8on), an integrated risk management framework faced by food-insecure communi8es struggling to improve their developed by Oxfam America and REST, together with Ethiopian lives and livelihoods will also increase. -

Estimating the Burden of Malaria in Senegal: Bayesian Zero-Inflated Binomial Geostatistical Modeling of the MIS 2008 Data

Estimating the Burden of Malaria in Senegal: Bayesian Zero-Inflated Binomial Geostatistical Modeling of the MIS 2008 Data Federica Giardina1,2, Laura Gosoniu1,2, Lassana Konate3, Mame Birame Diouf4, Robert Perry5, Oumar Gaye6, Ousmane Faye3, Penelope Vounatsou1,2* 1 Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland, 2 University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 3 Faculte´ des Sciences et Techniques, UCAD Dakar, Se´ne´gal, 4 National Malaria Control Programme, Dakar, Se´ne´gal, 5 Center for Global Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, 6 Faculte´ de Me´decine, Pharmacie et Odontologie, UCAD Dakar, Se´ne´gal Abstract The Research Center for Human Development in Dakar (CRDH) with the technical assistance of ICF Macro and the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) conducted in 2008/2009 the Senegal Malaria Indicator Survey (SMIS), the first nationally representative household survey collecting parasitological data and malaria-related indicators. In this paper, we present spatially explicit parasitaemia risk estimates and number of infected children below 5 years. Geostatistical Zero-Inflated Binomial models (ZIB) were developed to take into account the large number of zero-prevalence survey locations (70%) in the data. Bayesian variable selection methods were incorporated within a geostatistical framework in order to choose the best set of environmental and climatic covariates associated with the parasitaemia risk. Model validation confirmed that the ZIB model had a better predictive ability than the standard Binomial analogue. Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods were used for inference. Several insecticide treated nets (ITN) coverage indicators were calculated to assess the effectiveness of interventions. -

There Is Enormous Suffering” Serious Abuses Against Talibé Children in Senegal, 2017-2018

“There Is Enormous Suffering” Serious Abuses Against Talibé Children in Senegal, 2017-2018 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH “There Is Enormous Suffering” Serious Abuses Against Talibé Children in Senegal, 2017-2018 Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37380 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-37380 “There Is Enormous Suffering” Serious Abuses Against Talibé Children in Senegal, 2017-2018 Map 1: Locations of Research in Senegal ............................................................................. i Map 2: Talibé Migration Routes .......................................................................................... ii Terminology and Abbreviations ........................................................................................ -

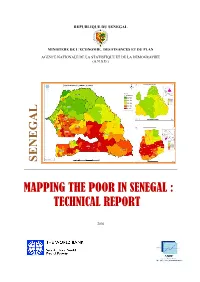

Senegal Mapping the Poor in Senegal : Technical Report

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DES FINANCES ET DU PLAN AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE (A.N.S.D.) SENEGAL MAPPING THE POOR IN SENEGAL : TECHNICAL REPORT 2016 MAPPING THE POOR IN SENEGAL: TECHNICAL REPORT DRAFT VERSION 1. Introduction Senegal has been successful on many fronts such as social stability and democratic development; its record of economic growth and poverty reduction however has been one of mixed results. The recently completed poverty assessment in Senegal (World Bank, 2015b) shows that national poverty rates fell by 6.9 percentage points between 2001/02 and 2005/06, but subsequent progress diminished to a mere 1.6 percentage point decline between 2005/06 and 2011, from 55.2 percent in 2001 to 48.3 percent in 2005/06 to 46.7 percent in 2011. In addition, large regional disparities across the regions within Senegal exist with poverty rates decreasing from North to South (with the notable exception of Dakar). The spatial pattern of poverty in Senegal can be explained by factors such as the lack of market access and connectivity in the more isolated regions to the East and South. Inequality remains at a moderately low level on a national basis but about two-thirds of overall inequality in Senegal is due to within-region inequality and between-region inequality as a share of total inequality has been on the rise during the 2000s. As a Sahelian country, Senegal faces a critical constraint, inadequate and unreliable rainfall, which limits the opportunities in the rural economy where the majority of the population still lives to differing extents across the regions.