Alterity and Minorities in Michael Radford's Merchant of Venice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloadable Text (Finkelstein and Mccleery 2006, 1)

A Book History Study of Michael Radford’s Filmic Production William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS of RHODES UNIVERSITY by BRYONY ROSE HUMPHRIES GREEN March 2008 ABSTRACT Falling within the ambit of the Department of English Literature but with interdisciplinary scope and method, the research undertaken in this thesis examines Michael Radford’s 2004 film production William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice using the Book History approach to textual study. Previously applied almost exclusively to the study of books, Book History examines the text in terms of both its medium and its content, bringing together bibliographical, literary and historical approaches to the study of books within one theoretical paradigm. My research extends this interdisciplinary approach into the filmic medium by using a modified version of Robert Darnton’s “communication circuit” to examine the process of transmission of this Shakespearean film adaptation from creation to reception. The research is not intended as a complete Book History study and even less as a comprehensive investigation of William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice . Rather, it uses a Shakespearean case study to bring together the two previously discrete fields of Book History and filmic investigation. Drawing on film studies, literary concepts, cultural and media studies, modern management theory as well as reception theories and with the use of both quantitative and qualitative data, I show Book History to be an eminently useful and constructive approach to the study of film. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank the Mandela Rhodes Foundation for the funding that allowed me to undertake a Master’s degree. -

Biography: Jocelyn Pook

Biography: Jocelyn Pook Jocelyn Pook is one of the UK’s most versatile composers, having written extensively for stage, screen, opera house and concert hall. She has established an international reputation as a highly original composer winning her numerous awards and nominations including a Golden Globe, an Olivier and two British Composer Awards. Often remembered for her film score to Eyes Wide Shut, which won her a Chicago Film Award and a Golden Globe nomination, Pook has worked with some of the world’s leading directors, musicians, artists and arts institutions – including Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, the Royal Opera House, BBC Proms, Andrew Motion, Peter Gabriel, Massive Attack and Laurie Anderson. Pook has also written film score to Michael Radford’s The Merchant of Venice with Al Pacino, which featured the voice of countertenor Andreas Scholl and was nominated for a Classical Brit Award. Other notable film scores include Brick Lane directed by Sarah Gavron and a piece for the soundtrack to Gangs of New York directed by Martin Scorsese. With a blossoming reputation as a composer of electro-acoustic works and music for the concert platform, Pook continues to celebrate the diversity of the human voice. Her first opera Ingerland was commissioned and produced by ROH2 for the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Studio in June 2010. The BBC Proms and The King’s Singers commissioned to collaborate with the Poet Laureate Andrew Motion on a work entitled Mobile. Portraits in Absentia was commissioned by BBC Radio 3 and is a collage of sound, voice, music and words woven from the messages left on her answerphone. -

Équinoxe Screenwriters' Workshop / Palais Schwarzenberg, Vienna 31

25. éQuinoxe Screenwriters’ Workshop / 31. October – 06. November 2005 Palais Schwarzenberg, Vienna ADVISORS THE SELECTED WRITERS THE SELECTED SCRIPTS DIE AUSGEWÄHLTEN DIE AUSGEWÄHLTEN AUTOREN DREHBÜCHER Dev BENEGAL (India) Lois AINSLIE (Great Britain) A Far Better Thing Yves DESCHAMPS (France) Andrea Maria DUSL (Austria) Channel 8 Florian FLICKER (Austria) Peter HOWEY (Great Britain) Czech Made James V. HART (USA) Oliver KEIDEL (Germany) Dr. Alemán Hannah HOLLINGER (Germany) Paul KIEFFER (Luxembourg) Arabian Nights David KEATING (Ireland) Jean-Louis LAVAL (France) Reclaimed Justice Danny KRAUSZ (Austria) Piotrek MULARUK (Poland) Yuma Susan B. LANDAU (USA) Gabriele NEUDECKER (Austria) ...Then I Started Killing God Marcia NASATIR (USA) Dominique STANDAERT (Belgium) Wonderful Eric PLESKOW (Austria / USA) Hans WEINGARTNER (Austria) Code 82 Lorenzo SEMPLE (USA) Martin SHERMAN (Great Britain) 2 25. éQuinoxe Screenwriters‘ Workshop / 31. October - 06. November 2005 Palais Schwarzenberg, Vienna: TABLE OF CONTENTS / INHALT Foreword 4 The Selected Writers 30 - 31 Lois AINSLIE (Great Britain) – A FAR BETTER THING 32 The Story of éQuinoxe / To Be Continued 5 Andrea Maria DUSL (Austria) – CHANNEL 8 33 Peter HOWEY (Great Britain) – CZECH MADE 34 Interview with Noëlle Deschamps 8 Oliver KEIDEL (Germany) – DR. ALEMÁN 35 Paul KIEFFER (Luxembourg) – ARABIAN NIGHTS 36 From Script to Screen: 1993 – 2005 12 Jean Louis LAVAL (France) – RECLAIMED JUSTICE 37 Piotrek MULARUK (Poland) – YUMA 38 25. éQuinoxe Screenwriters‘ Workshop Gabriele NEUDECKER (Austria) – ... TEHN I STARTED KILLING GOD 39 The Advisors 16 Dominique STANDAERT (Belgium) – WONDERFUL 40 Dev BENEGAL (India) 17 Hans WEINGARTNER (Austria) – CODE 82 41 Yves DESCHAMPS (France) 18 Florian FLICKER (Austria) 19 Special Sessions / Media Lawyer Dr. Stefan Rüll 42 Jim HART (USA) 20 Master Classes / Documentary Filmmakers 44 Hannah HOLLINGER (Germany) 21 David KEATING (Ireland) 22 The Global éQuinoxe Network: The Correspondents 46 Danny KRAUSZ (Austria) 23 Susan B. -

5 Under 30 Young Photographers’ Competition

5 UNDER 30 YOUNG PHOTOGRAPHERS’ COMPETITION Opening: Daniel Blau is pleased to announce the winners of the 30th June, 6pm - 8pm gallery’s third annual Young Photographers’ Competition: Exhibition: Melissa Arras / Alan Knox July 1st - July 31st, 2015 Julia Parks / Michael Radford Tuesday - Friday, 11 - 6 pm We are delighted to present a selection of these talented For further information photographers’ works in a group exhibition. about our exhibition please email: [email protected] Daniel Blau 51 Hoxton Square London, N1 6PB tel +44 (0)207 831 7998 Galerie Daniel Blau Maximilianstr. 26 80539 München Germany tel +49 (0)89 29 73 42 www.danielblau.com Thank you to Frontier Lager for sponsoring the opening of 5 UNDER 30 For sales enquiries please contact Gita at [email protected] MELISSA ARRAS El Dorado documents refugee camps in Calais. The town has, in recent years, become a doorway for many refugees risking their lives to leave their homelands. The work is a visual exploration into the duality of these situations, contemplating both the political tensions and the personal instability these transferrals involve. Recently, the town transformed from a seaside resort into an uncontrolled site populated with refugees hoping to enter the UK. Melissa’s work bravely captures intimate moments in the migrants’ lives whilst temporarily anchored in this new, surreal environment, proving their desperation in attaining stability. The work compellingly highlights the conditions faced by most migrants worldwide during these challenging times of relocation. Melissa Arras was born in 1994 in London. She received her BA in Photography from Middlesex University in July 2015. -

Extreme Surveillance and Preventive Justice

EXTREME SURVEILLANCE AND PREVENTIVE JUSTICE: NARRATION AND SPECTACULARITY IN MINORITY REPORT Noemí Novell [email protected] SUMMARY hrough a compared analysis between the narrative of Philip K. Dick and the filmic imagery of Steven Spielberg, the present article explores the forms in which dominant ideas around surveillance and preventive justice are portrayed in Minority Report. The author examines the links between literary fiction and audiovisual representation, focusing on the notions of narrative and spectacularity in order to establish up to what point does the film adaptation interpret de innovative and challenging ideas that identify Dick's visionary science fiction writing. KEY WORDS Science Fiction, Crime, Extreme surveillance, Preventive justice, Civil rights, National security, Privacy, State control, Dystopia, Panopticon, Film adaptation, Philip K. Dick, Steven Spielberg, Minority Report ARTICLE Based on “The Minority Report” (1956), by Philip K. Dick, Minority Report (Steven Spielberg, 2002) is, without a doubt, one of the film scripts that most highlights the ideas of surveillance of citizens and preventive justice.1 Although it is undeniable that both ideas are taken from the original story by Dick, in the film they are highlighted and modified, to some extent thanks to the audiovisual narration that sustains and supports them. This is a relevant point since sometimes opinion has tended towards the idea that cinematographic, unlike literary, science fiction, strips this genre of the innovative and non-conformist ideas that characterise it, and that it lingers too long on the special effects, which, from this perspective, would slow down the narration and would add nothing to it.2 This, this article seeks to explore the ways in which the dominant ideas of surveillance and preventive justice are shown in Minority Report and how their audiovisual representation, far from hindering, contribute to better illustrating the dominant ideas of the film. -

P R O G R a M M E WELCOME

2 0 1 8 PROGRAMME WELCOME he twelfth Cromarty Film Festival has a well-rounded sound to it — who would have thought we would get to the dozen ? This one has excellent guests — our Scots Makar (poet) Jackie Kay, actor Gregor Fisher, Tdirectors Michael Radford, Molly Dineen and Callum Macrae among them. ¶We’ll be celebrating the glories ✶ of Midnight Cowboy and Double Indemnity, exploring the making of 1984 with its director, and featuring the powerful new documentaries Being Blacker and The Ballymurphy Precedent among a veritable bouquet of archive, debuts, blockbusters, shorts, couthy gems and zombies. ¶The winter winds blew off the Atlantic early this year, so instead of attending the first planning meeting of the Film Festival, due to ferry cancellations I was sitting on my bed in Stornoway viewing the event by FaceTime. What I saw in blurry wide shot, was the Committee, working, laughing, drinking and deciding. A group of disparate and dedicated volunteers bonded by their love of film and Cromarty. Between them they have created CONTENTS something very special. ¶Viewing it from afar was a good experience for me as this is my last year on the Committee and it felt like I was already slipping away. Each year we pass on to new members like a creative relay. The Festival Cromarty .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 is in safe hands. ¶I have had a great time working for the Festival and I know it will, dependent on funding, go on Ticket information. 2 astounding us with the warm immediacy of viewing films together, our guests helping to illuminate the experience. -

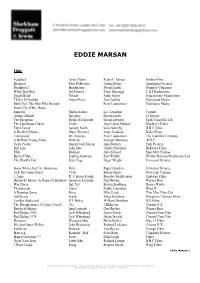

Eddie Marsan

EDDIE MARSAN Film: Feedback Jarvis Dolan Pedro C Alonso Ombra Films Backseat Paul Wolfowitz Adam Mckay Annapurna Pictures Deadpool 2 Headmaster David Leitch Donners' Company White Boy Rick Art Derrick Yann Demange L B I Productions Jungle Book Vihaan Andy Serkis Imaginarium Productions 7 Days In Entebbe Simon Peres Jose Padilha Participant Media Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Peter Landesman Endurance Media Down The White House Emperor Martin Luther Lee Tamahori Corrino Atomic Blonde Spyglass David Leitch 87 Eleven The Exception Heinrich Himmler David Leveaux Egoli Tossell K L K The Limehouse Golem Uncle Juan Carlos Medina Number 9 Films Their Finest Sammy Smith Lone Scherfig B B C Films A Kind Of Murder Marty Kimmel Andy Goddard Killer Films Concussion Dr. Dekosky Peter Landesman The Cantillon Company A Brilliant Young Mind Richard Morgan Matthews B B C God's Pocket Smilin' Jack Moran John Slattery Park Pictures Still Life John May Uberto Passolini Redwave Films Filth Bladesy John S Baird Steel Mill Pictures Best Of Men Ludwig Guttman Tim Whitby Whitby Davison Productions Ltd The World's End Peter Page Edgar Wright Universal Pictures Snow White And The Huntsman Duir Rupert Sanders Universal Pictures Jack The Giant Slayer Craw Bryan Singer New Line Cinema I, Anna D. I. Kevin Franks Barnaby Southcombe Embargo Films Sherlock Holmes: A Game Of Shadows Inspector Lestrade Guy Ritchie Warner Bros War Horse Sgt. Fry Steven Spielberg Dream Works Tyrannosaur James Paddy Considine Warp X A Running Jump Perry Mike Leigh Thin Man Films Ltd Junkhearts Frank Tinge Krishnan Disruptive Element Films London Boulevard D I. -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas -

Culture and Customs of Kenya

Culture and Customs of Kenya NEAL SOBANIA GREENWOOD PRESS Culture and Customs of Kenya Cities and towns of Kenya. Culture and Customs of Kenya 4 NEAL SOBANIA Culture and Customs of Africa Toyin Falola, Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sobania, N. W. Culture and customs of Kenya / Neal Sobania. p. cm.––(Culture and customs of Africa, ISSN 1530–8367) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–31486–1 (alk. paper) 1. Ethnology––Kenya. 2. Kenya––Social life and customs. I. Title. II. Series. GN659.K4 .S63 2003 305.8´0096762––dc21 2002035219 British Library Cataloging in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2003 by Neal Sobania All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2002035219 ISBN: 0–313–31486–1 ISSN: 1530–8367 First published in 2003 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 For Liz Contents Series Foreword ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Chronology xvii 1 Introduction 1 2 Religion and Worldview 33 3 Literature, Film, and Media 61 4 Art, Architecture, and Housing 85 5 Cuisine and Traditional Dress 113 6 Gender Roles, Marriage, and Family 135 7 Social Customs and Lifestyle 159 8 Music and Dance 187 Glossary 211 Bibliographic Essay 217 Index 227 Series Foreword AFRICA is a vast continent, the second largest, after Asia. -

List of Surveillance Feature Films

Surveillance Feature Films compiled by Dietmar Kammerer, Berlin Sources of plot descriptions and details: allmovie.com; imdb.com 1984 (Nineteen Eighty-Four) UK 1956 dir: Michael Anderson. George Orwell's novel of a totalitarian future society in which a man whose daily work is rewriting history tries to rebel by falling in love. keywords: literary adaptation; dystopic future http://www.allmovie.com/work/1984-104070 http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0048918/ 1984 (Nineteen Eighty-Four) UK 1984 dir: Michael Radford Second adaptation of George Orwell's novel. keywords: literary adaptation; dystopic future http://www.allmovie.com/work/1984-91 http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0087803/ 23 [23 – Nichts ist wie es scheint] Germany 1998 dir: Hans-Christian Schmid The movie's plot is based on the true story of a group of young computer hackers from Hannover, Germany. In the late 1980s the orphaned Karl Koch invests his heritage in a flat and a home computer. At first he dials up to bulletin boards to discuss conspiracy theories inspired by his favorite novel, R.A. Wilson's "Illuminatus", but soon he and his friend David start breaking into government and military computers. Pepe, one of Karl's rather criminal acquaintances senses that there is money in computer cracking - he travels to east Berlin and tries to contact the KGB. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0126765/ http://www.allmovie.com/work/23-168222 keywords: conspiracy; internet; true story The Anderson Tapes USA 1971 dir: Sidney Lumet This breathlessly paced high-tech thriller stars Sean Connery as Anderson, a career criminal who's just been released from his latest prison term. -

John Sessions

JOHN SESSIONS Film: Finding Your Feet Mike Richard Loncraine Eclipse Films Intrigo: Dear Agnes Pumpermann Daniel Alfredson Enderby Entertainment Alice In Wonderland: Humpty Dumpty Bill Condon Walt Disney Through The Looking Glass (voice) Loving Vincent Pere Tanguy Dorota Kobiela Trademark Films Denial Prof. Richard Evans Mick Jackson B B C Films Florence Foster Jenkins Dr. Hermann Stephen Frears Qwerty Films The Rack Pack Ted Lowe Brian Welsh Black Gate Pictures Legend Lord Boothby Brian Helgeland Working Title The Silent Storm Mr Smith Corinna Mcfarlane Neon Films Mr Holmes Mycroft Holmes Bill Condon See Saw Films Pudsey Thorne Nick Moore Vertigo Films Filth Toal Jon S Baird Steel Mill Iron Lady Edward Heath Phyllida Lloyd Pathe The Real American: Joe Mc Carthy Joe Mc Carthy Lutz Hachmeister Elkon Media Gmbh The Domino Effect Talk Show Host Paul Van Der Oest Kasander Film Spies And Lies Major Kenneth Folkes Simon Bennett South Pacific Pictures Prods Made In Dagenham Harold Wilson Nigel Cole Number 9 Films The Making Of Plus One Line Producer Mary Mcguckian Pembridge Pictures Nativity Headmaster / Mr Lore Debbie Isitt Mirrorball Films The Last Station Dushan Michael Hoffman Zephry Films Inconceivable Finbar Darrow Mary Mcguckian Pembridge Pictures Intervention Joe Mary Mcguckian Pembridge Pictures The Good Shepherd Valentin Robert De Niro Universal Ragtale Felix Sty Mary Mcguckian Pembridge Pictures The Merchant Of Venice Salario Michael Radford Avenue Pictures Five Children And It Peasemarsh John Stephenson Feel Films Lighthouse Hill Mr. Reynard David Fairman Carnaby Films Gangs Of New York Edwin Forrest Martin Scorsese Miramax One Of The Hollywood Ten Paul Jarrico Karl Francis Bloom Street Productions High Heels And Low Lifes The Director Mel Smith Touchstone A Midsummer Night's Dream Philostrate Michael Hoffman Fox The Scarlet Tunic Humphrey Gould Stuart St. -

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory