Downloadable Text (Finkelstein and Mccleery 2006, 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breathtaking Stories of Extreme Filming. Read the Full Story on Page 6

The newspaper for BBC pensioners - with highlights from Ariel Heights, Camera, Action Breathtaking stories of extreme filming. Read the full story on page 6. June 2011 • Issue 4 Yes, Prime Lord Patten Minister back takes the helm Sounds better? on stage Page 2 Page 7 Page 12 NEWS • LifE aftEr auNtiE • CLaSSifiEdS • Your LEttErS • obituariES • CroSPEro 02 uPdatE froM thE bbC Patten takes helm at BBC Trust On 3 May, Lord Patten began his appointment as chairman of the BBC Trust – with an interesting first day spent taking questions from staff in a ringmain session. Quality First) should be all about and I hope we’ll be able to discuss options with the Executive during the summer.’ 2011 pay offer It is also apparent that the new chairman is ready and willing to deal with the – an update repercussions of the less popular decisions to be taken, and those which will not always Further to requests by the unions for all be accepted gladly by the licence fee payer. staff in bands 2-11 to be awarded a pay ‘I hope we won’t be talking about closing increase which is ‘substantially above services but, whatever we are talking about inflation’, the BBC has offered a 2% doing, if the Trust and the Executive are increase – which falls far short of the agreed it is the best way of using the money Retail Prices Index (RPI) figures on which then we have to stand by the consequences. If it is intended to be based (5.2% as at that involves answering thousands of emails, April 2011). -

BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM at CANNES British Entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’Ve Got to Talk About Kevin Dir

London May 10 2011: For immediate release BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM AT CANNES British entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’ve Got to Talk About Kevin dir. Lynne Ramsay UK Film Centre supports delegates with packed events programme 320 British films for sale in the market A Clockwork Orange in Cannes Classics The UK film industry comes to Cannes celebrating the selection of Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin for the official competition line-up at this year’s festival, Duane Hopkins’s short film, Cigarette at Night, in the Directors’ Fortnight and the restoration of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, restored by Warner Bros; in Cannes Classics. Lynne Ramsay’s We Need To Talk About Kevin starring Tilda Swinton was co-funded by the UK Film Council, whose film funding activities have now transferred to the BFI. Duane Hopkins is a director who was supported by the UK Film Council with his short Love Me and Leave Me Alone and his first feature Better Things. Actor Malcolm McDowell will be present for the screening of A Clockwork Orange. ITV Studios’ restoration of A Night to Remember will be screened in the Cinema on the Beach, complete with deckchairs. British acting talent will be seen in many films across the festival including Carey Mulligan in competition film Drive, and Tom Hiddleston & Michael Sheen in Woody Allen's opening night Midnight in Paris The UK Film Centre offers a unique range of opportunities for film professionals, with events that include Tilda Swinton, Lynne Ramsay and Luc Roeg discussing We Need to Talk About Kevin, The King’s Speech producers Iain Canning and Gareth Unwin discussing the secrets of the film’s success, BBC Film’s Christine Langan In the Spotlight and directors Nicolas Winding Refn and Shekhar Kapur in conversation. -

We Need to Talk About Subsidy: Television and the UK Film Industry – a Thirty-Year Relationship

We Need To Talk About Subsidy: Television and the UK film industry – a thirty-year relationship. I want to conclude this panel by taking a broader perspective on the concept of film subsidy, as deployed by Film4 and BBC Films, respectively the film production arms of the UK’s major public broadcasters Channel 4 and the BBC. As well as indicating the distinctive features of this model within the economic structure of the UK film industry, the paper will offer some consideration of the kind of film product these interventions has tended to produce. It will conclude with an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of what I want to call the cultural subsidy model of film production, and raise some general questions arising from the relationship between the film and television industries. In 2010, having been producing feature films in one form or another for twenty years, the BBC (the UK’s unique flagship PSB), produced its first explicit film strategy: ‘There are three principal public sector bodies which support film: BBC Films, Film4 (part of Channel 4) and UK Film Council (UKFC) (now merged with BFI)… This set up has provided the British film industry with stability and plurality which has been very important in the development and sustainability of the industry over the last decade’ (BBC Films Strategy, 2010). The confidence with which it trumpeted its own role in contributing ‘stability and plurality’ to the British film industry belied its protracted soul-searching about whether cinema was something the licence fee should really be spent on. Long-held anxiety within the Corporation that the licence levied on every household that owns a TV set should be spent on television content rather than movies the public has to pay again to see at the cinema, characterised the BBC’s ambivalence about following the film sponsorship model pioneered by Channel 4 from 1982. -

Biography: Jocelyn Pook

Biography: Jocelyn Pook Jocelyn Pook is one of the UK’s most versatile composers, having written extensively for stage, screen, opera house and concert hall. She has established an international reputation as a highly original composer winning her numerous awards and nominations including a Golden Globe, an Olivier and two British Composer Awards. Often remembered for her film score to Eyes Wide Shut, which won her a Chicago Film Award and a Golden Globe nomination, Pook has worked with some of the world’s leading directors, musicians, artists and arts institutions – including Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, the Royal Opera House, BBC Proms, Andrew Motion, Peter Gabriel, Massive Attack and Laurie Anderson. Pook has also written film score to Michael Radford’s The Merchant of Venice with Al Pacino, which featured the voice of countertenor Andreas Scholl and was nominated for a Classical Brit Award. Other notable film scores include Brick Lane directed by Sarah Gavron and a piece for the soundtrack to Gangs of New York directed by Martin Scorsese. With a blossoming reputation as a composer of electro-acoustic works and music for the concert platform, Pook continues to celebrate the diversity of the human voice. Her first opera Ingerland was commissioned and produced by ROH2 for the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Studio in June 2010. The BBC Proms and The King’s Singers commissioned to collaborate with the Poet Laureate Andrew Motion on a work entitled Mobile. Portraits in Absentia was commissioned by BBC Radio 3 and is a collage of sound, voice, music and words woven from the messages left on her answerphone. -

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: a Critical Introduction

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: A Critical Introduction Vital Statistics General Population: 64.1m Size: 241.9 km sq GDP: £1.9tr (€2.1tr) Film1 Market share of UK independent films in 2015: 10.5% Number of feature films produced: 201 Average visits to cinema per person per year: 2.7 Production spend per year: £1.4m (€1.6) TV2 Audience share of the main publicly-funded PSB (BBC): 72% Production spend by PSBs: £2.5bn (€3.2bn) Production spend by commercial channels (excluding sport): £350m (€387m) Time spent watching television per day: 193 minutes (3hrs 13 minutes) Introduction This chapter provides an overview of independent film and television production in the UK. Despite the unprecedented levels of convergence that characterise the digital era, the UK film and television industries remain distinct for several reasons. The film industry is small and fragmented, divided across the two opposing sources of support on which it depends: large but uncontrollable levels of ‘inward-investment’ – money invested in the UK from overseas – mainly from the US, and low levels of public subsidy. By comparison, the television industry is large and diverse, its relative stability underpinned by a long-standing infrastructure of 1 Sources: BFI 2016: 10; ‘The Box Office 2015’ [market share of UK indie films] ; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [cinema visits per per person]; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [average visits per person]; BFI 2016: 3; ‘Screen Sector Production’ [production spend per year]. 2 Sources: Oliver & Ohlbaum 2016: 68 [PSB audience share]; Ofcom 2015a: 3 [PSB production spend]; Ofcom 2015a: 8. -

September/October 2014 at BFI Southbank

September/October 2014 at BFI Southbank Al Pacino in Conversation with Salome & Wilde Salome, Jim Jarmusch and Friends, Peter Lorre, Night Will Fall, The Wednesday Play at 50 and Fela Kuti Al Pacino’s Salomé and Wilde Salomé based on Oscar Wilde’s play, will screen at BFI Southbank on Sunday 21 September and followed by a Q&A with Academy Award winner Al Pacino and Academy Award nominee Jessica Chastain that will be broadcast live via satellite to cinemas across the UK and Ireland. This unique event will be hosted by Stephen Fry. Jim Jarmusch was one of the key filmmakers involved in the US indie scene that flourished from the mid-70s to the late 90s. He has succeeded in remaining true to the spirit of independence, with films such as Stranger Than Paradise (1984), Dead Man (1995) and, most recently, Only Lovers Left Alive (2013). With the re-release of Down By Law (1986) as a centrepiece for the season, we will also look at films that have inspired Jarmusch A Century of Chinese Cinema: New Directions will celebrate the sexy, provocative and daring work by acclaimed contemporary filmmakers such as Wong Kar-wai, Jia Zhangke, Wang Xiaoshuai and Tsai Ming-liang. These directors built on the innovations of the New Wave era and sparked a renewed global interest in Chinese cinema into the new millennium André Singer’s powerful new documentary Night Will Fall (2014) reveals for the first time the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps and the efforts made by army and newsreel cameramen to document the almost unbelievable scenes encountered there. -

Équinoxe Screenwriters' Workshop / Palais Schwarzenberg, Vienna 31

25. éQuinoxe Screenwriters’ Workshop / 31. October – 06. November 2005 Palais Schwarzenberg, Vienna ADVISORS THE SELECTED WRITERS THE SELECTED SCRIPTS DIE AUSGEWÄHLTEN DIE AUSGEWÄHLTEN AUTOREN DREHBÜCHER Dev BENEGAL (India) Lois AINSLIE (Great Britain) A Far Better Thing Yves DESCHAMPS (France) Andrea Maria DUSL (Austria) Channel 8 Florian FLICKER (Austria) Peter HOWEY (Great Britain) Czech Made James V. HART (USA) Oliver KEIDEL (Germany) Dr. Alemán Hannah HOLLINGER (Germany) Paul KIEFFER (Luxembourg) Arabian Nights David KEATING (Ireland) Jean-Louis LAVAL (France) Reclaimed Justice Danny KRAUSZ (Austria) Piotrek MULARUK (Poland) Yuma Susan B. LANDAU (USA) Gabriele NEUDECKER (Austria) ...Then I Started Killing God Marcia NASATIR (USA) Dominique STANDAERT (Belgium) Wonderful Eric PLESKOW (Austria / USA) Hans WEINGARTNER (Austria) Code 82 Lorenzo SEMPLE (USA) Martin SHERMAN (Great Britain) 2 25. éQuinoxe Screenwriters‘ Workshop / 31. October - 06. November 2005 Palais Schwarzenberg, Vienna: TABLE OF CONTENTS / INHALT Foreword 4 The Selected Writers 30 - 31 Lois AINSLIE (Great Britain) – A FAR BETTER THING 32 The Story of éQuinoxe / To Be Continued 5 Andrea Maria DUSL (Austria) – CHANNEL 8 33 Peter HOWEY (Great Britain) – CZECH MADE 34 Interview with Noëlle Deschamps 8 Oliver KEIDEL (Germany) – DR. ALEMÁN 35 Paul KIEFFER (Luxembourg) – ARABIAN NIGHTS 36 From Script to Screen: 1993 – 2005 12 Jean Louis LAVAL (France) – RECLAIMED JUSTICE 37 Piotrek MULARUK (Poland) – YUMA 38 25. éQuinoxe Screenwriters‘ Workshop Gabriele NEUDECKER (Austria) – ... TEHN I STARTED KILLING GOD 39 The Advisors 16 Dominique STANDAERT (Belgium) – WONDERFUL 40 Dev BENEGAL (India) 17 Hans WEINGARTNER (Austria) – CODE 82 41 Yves DESCHAMPS (France) 18 Florian FLICKER (Austria) 19 Special Sessions / Media Lawyer Dr. Stefan Rüll 42 Jim HART (USA) 20 Master Classes / Documentary Filmmakers 44 Hannah HOLLINGER (Germany) 21 David KEATING (Ireland) 22 The Global éQuinoxe Network: The Correspondents 46 Danny KRAUSZ (Austria) 23 Susan B. -

5 Under 30 Young Photographers’ Competition

5 UNDER 30 YOUNG PHOTOGRAPHERS’ COMPETITION Opening: Daniel Blau is pleased to announce the winners of the 30th June, 6pm - 8pm gallery’s third annual Young Photographers’ Competition: Exhibition: Melissa Arras / Alan Knox July 1st - July 31st, 2015 Julia Parks / Michael Radford Tuesday - Friday, 11 - 6 pm We are delighted to present a selection of these talented For further information photographers’ works in a group exhibition. about our exhibition please email: [email protected] Daniel Blau 51 Hoxton Square London, N1 6PB tel +44 (0)207 831 7998 Galerie Daniel Blau Maximilianstr. 26 80539 München Germany tel +49 (0)89 29 73 42 www.danielblau.com Thank you to Frontier Lager for sponsoring the opening of 5 UNDER 30 For sales enquiries please contact Gita at [email protected] MELISSA ARRAS El Dorado documents refugee camps in Calais. The town has, in recent years, become a doorway for many refugees risking their lives to leave their homelands. The work is a visual exploration into the duality of these situations, contemplating both the political tensions and the personal instability these transferrals involve. Recently, the town transformed from a seaside resort into an uncontrolled site populated with refugees hoping to enter the UK. Melissa’s work bravely captures intimate moments in the migrants’ lives whilst temporarily anchored in this new, surreal environment, proving their desperation in attaining stability. The work compellingly highlights the conditions faced by most migrants worldwide during these challenging times of relocation. Melissa Arras was born in 1994 in London. She received her BA in Photography from Middlesex University in July 2015. -

The History of the Development of British Satellite Broadcasting Policy, 1977-1992

THE HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF BRITISH SATELLITE BROADCASTING POLICY, 1977-1992 Windsor John Holden —......., Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD University of Leeds, Institute of Communications Studies July, 1998 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others ABSTRACT This thesis traces the development of British satellite broadcasting policy, from the early proposals drawn up by the Home Office following the UK's allocation of five direct broadcast by satellite (DBS) frequencies at the 1977 World Administrative Radio Conference (WARC), through the successive, abortive DBS initiatives of the BBC and the "Club of 21", to the short-lived service provided by British Satellite Broadcasting (BSB). It also details at length the history of Sky Television, an organisation that operated beyond the parameters of existing legislation, which successfully competed (and merged) with BSB, and which shaped the way in which policy was developed. It contends that throughout the 1980s satellite broadcasting policy ceased to drive and became driven, and that the failure of policy-making in this time can be ascribed to conflict on ideological, governmental and organisational levels. Finally, it considers the impact that satellite broadcasting has had upon the British broadcasting structure as a whole. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Contents ii Acknowledgements 1 INTRODUCTION 3 British broadcasting policy - a brief history -

Extreme Surveillance and Preventive Justice

EXTREME SURVEILLANCE AND PREVENTIVE JUSTICE: NARRATION AND SPECTACULARITY IN MINORITY REPORT Noemí Novell [email protected] SUMMARY hrough a compared analysis between the narrative of Philip K. Dick and the filmic imagery of Steven Spielberg, the present article explores the forms in which dominant ideas around surveillance and preventive justice are portrayed in Minority Report. The author examines the links between literary fiction and audiovisual representation, focusing on the notions of narrative and spectacularity in order to establish up to what point does the film adaptation interpret de innovative and challenging ideas that identify Dick's visionary science fiction writing. KEY WORDS Science Fiction, Crime, Extreme surveillance, Preventive justice, Civil rights, National security, Privacy, State control, Dystopia, Panopticon, Film adaptation, Philip K. Dick, Steven Spielberg, Minority Report ARTICLE Based on “The Minority Report” (1956), by Philip K. Dick, Minority Report (Steven Spielberg, 2002) is, without a doubt, one of the film scripts that most highlights the ideas of surveillance of citizens and preventive justice.1 Although it is undeniable that both ideas are taken from the original story by Dick, in the film they are highlighted and modified, to some extent thanks to the audiovisual narration that sustains and supports them. This is a relevant point since sometimes opinion has tended towards the idea that cinematographic, unlike literary, science fiction, strips this genre of the innovative and non-conformist ideas that characterise it, and that it lingers too long on the special effects, which, from this perspective, would slow down the narration and would add nothing to it.2 This, this article seeks to explore the ways in which the dominant ideas of surveillance and preventive justice are shown in Minority Report and how their audiovisual representation, far from hindering, contribute to better illustrating the dominant ideas of the film. -

P R O G R a M M E WELCOME

2 0 1 8 PROGRAMME WELCOME he twelfth Cromarty Film Festival has a well-rounded sound to it — who would have thought we would get to the dozen ? This one has excellent guests — our Scots Makar (poet) Jackie Kay, actor Gregor Fisher, Tdirectors Michael Radford, Molly Dineen and Callum Macrae among them. ¶We’ll be celebrating the glories ✶ of Midnight Cowboy and Double Indemnity, exploring the making of 1984 with its director, and featuring the powerful new documentaries Being Blacker and The Ballymurphy Precedent among a veritable bouquet of archive, debuts, blockbusters, shorts, couthy gems and zombies. ¶The winter winds blew off the Atlantic early this year, so instead of attending the first planning meeting of the Film Festival, due to ferry cancellations I was sitting on my bed in Stornoway viewing the event by FaceTime. What I saw in blurry wide shot, was the Committee, working, laughing, drinking and deciding. A group of disparate and dedicated volunteers bonded by their love of film and Cromarty. Between them they have created CONTENTS something very special. ¶Viewing it from afar was a good experience for me as this is my last year on the Committee and it felt like I was already slipping away. Each year we pass on to new members like a creative relay. The Festival Cromarty .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 is in safe hands. ¶I have had a great time working for the Festival and I know it will, dependent on funding, go on Ticket information. 2 astounding us with the warm immediacy of viewing films together, our guests helping to illuminate the experience. -

Eddie Marsan

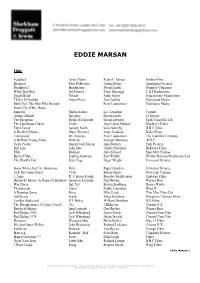

EDDIE MARSAN Film: Feedback Jarvis Dolan Pedro C Alonso Ombra Films Backseat Paul Wolfowitz Adam Mckay Annapurna Pictures Deadpool 2 Headmaster David Leitch Donners' Company White Boy Rick Art Derrick Yann Demange L B I Productions Jungle Book Vihaan Andy Serkis Imaginarium Productions 7 Days In Entebbe Simon Peres Jose Padilha Participant Media Mark Felt: The Man Who Brought Peter Landesman Endurance Media Down The White House Emperor Martin Luther Lee Tamahori Corrino Atomic Blonde Spyglass David Leitch 87 Eleven The Exception Heinrich Himmler David Leveaux Egoli Tossell K L K The Limehouse Golem Uncle Juan Carlos Medina Number 9 Films Their Finest Sammy Smith Lone Scherfig B B C Films A Kind Of Murder Marty Kimmel Andy Goddard Killer Films Concussion Dr. Dekosky Peter Landesman The Cantillon Company A Brilliant Young Mind Richard Morgan Matthews B B C God's Pocket Smilin' Jack Moran John Slattery Park Pictures Still Life John May Uberto Passolini Redwave Films Filth Bladesy John S Baird Steel Mill Pictures Best Of Men Ludwig Guttman Tim Whitby Whitby Davison Productions Ltd The World's End Peter Page Edgar Wright Universal Pictures Snow White And The Huntsman Duir Rupert Sanders Universal Pictures Jack The Giant Slayer Craw Bryan Singer New Line Cinema I, Anna D. I. Kevin Franks Barnaby Southcombe Embargo Films Sherlock Holmes: A Game Of Shadows Inspector Lestrade Guy Ritchie Warner Bros War Horse Sgt. Fry Steven Spielberg Dream Works Tyrannosaur James Paddy Considine Warp X A Running Jump Perry Mike Leigh Thin Man Films Ltd Junkhearts Frank Tinge Krishnan Disruptive Element Films London Boulevard D I.