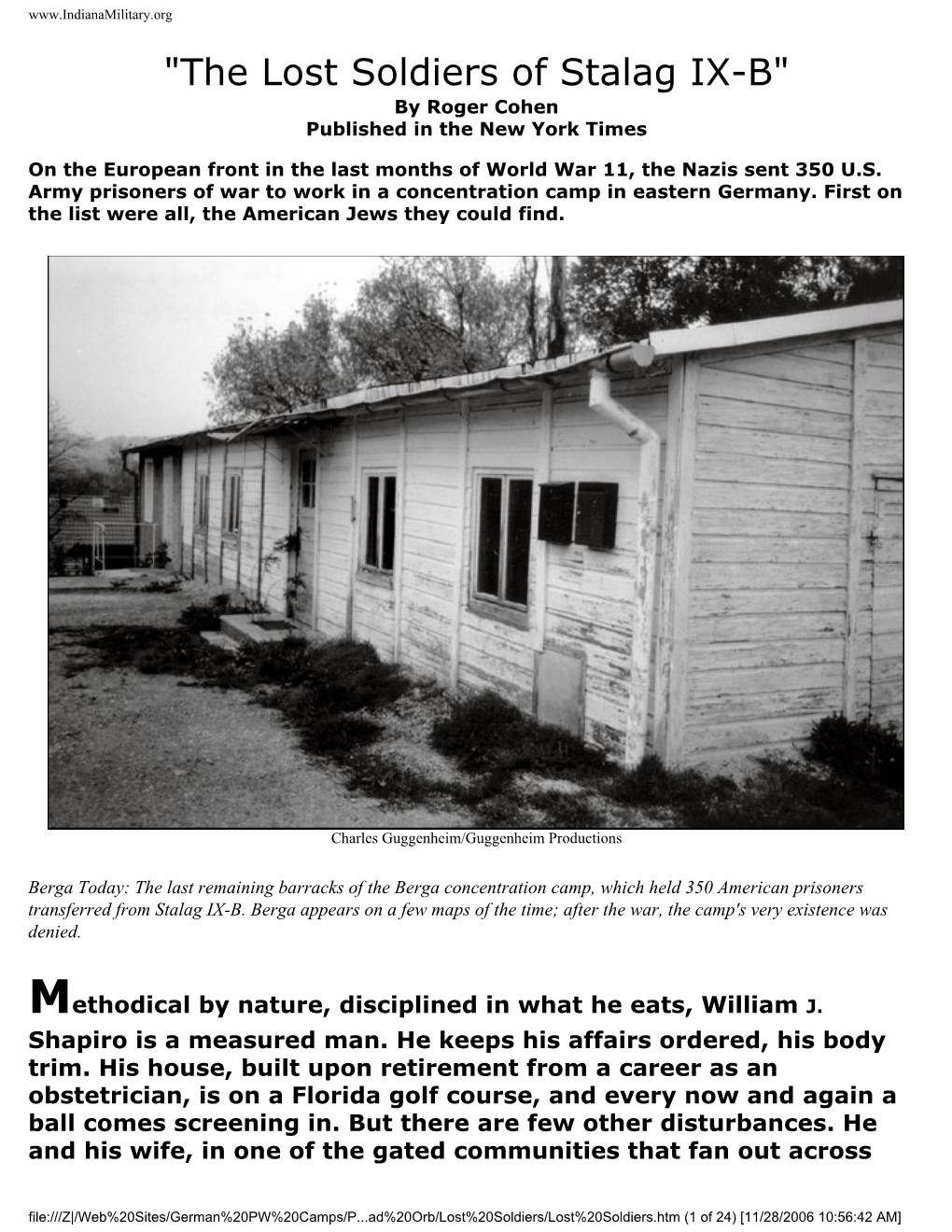

"The Lost Soldiers of Stalag IX-B" by Roger Cohen Published in the New York Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High School Guide

2018-19 Cincinnati Public Schools High School Guide Prepared for Life What’s Inside Superintendent's Message .................................................................... 2 Graduation Requirements ...................................................................... 3 Career and Technical Education Programs ............................................ 4 My Tomorrow Initiative .......................................................................... 5 Important Information about the High School Application Process ..... 6-7 Lottery Rounds and Waiting List Details .............................................. 8 CPS Students Applying to CPS – In District ......................................... 9 Applying to Upper Grades in CPS High Schools .................................. 10 Non-CPS Students Applying to CPS – In District and Out of District ... 11 Sports and Extracurricular Activities ..................................................... 12-14 Aiken High School .............................................................................. 15-16 Carpe Diem Innovative School – Cincinnati (A CPS-sponsored charter school) ........................................................ 17-18 Cincinnati Digital Academy .................................................................... 19-20 Clark Montessori High School ............................................................... 21-22 Dater High School .................................................................................. 23-24 Map of High School Locations ............................................................ -

GOLDEN LION � Vol 59 - No

THE ARDENNES * THE RHINELAND * CENTRAL EUROPE UB PUBLISH' D BY AND fOli The Veterans of the 106th INFANTRY INVISION GOLDEN LION Vol 59 - No. 3 APR - MAY - JUN 2003 Major Steven Wall, of TACOM's Brigade Combat Team presents John M. "Jack" Roberts, "Michigan's Mini-Reunion Organizer" with a WWII Memorial Flag. See story in Mini-Reunion Section Board of Directors The CUB John 0. Gilliland, 592/SV (2003) A quarterly publication of the 140 Nancy Strut, Boaz, AL 35957 106th Infantry Division Association, Inc. 256-593-6801 A nonprofit Organization - USPO #5054 Frank Lapato, 422/HQ (2003) ' St Paul, MN - Agent: John P Kline, Editor RD 8, Box 403, Kittanning, PA 16201 Membership fees include CUB subscription 724-548-2119 Email: flapato@ alltel.net Paid membershipMay 7, 2003 -1,603 Harry F. Martin, Jr, 424/L (2003) PO Box 221, Mount Arlington, NJ 07856 973-663-2410 madinjr@localnetcom President John IL Schaffner George Peres, 590/A Past-President (Ex-Officio) . Joseph P. Maloney (2003) 19160 HaabocTree Court, NW Fort Myers, PL 33903 1st Vice-Pres John M. Roberts 941-731-5320 2nd Vice-Pres Walter G. Bridges Charles F. Meek 422/H (2003):, Historian Sherod Collins 7316 Voss Parkway, Middleton, WI 53562 608-831-6110 Adjutant Marion Ray CUB Editor, Membership John P. Kline Pete Yanchik, 423/A (2004).4 Chaplain Dr. Duncan Trueman 1161 Airport Road, Aliquippa, PA 15001-4312 eh Memorials Chairman Dr. John G. Robb 412-375-6451 Richard L. Rigatti, 423/B (2004) Atterbury Memorial Representative Philip Cox 113 Woodshire Drive, Pittsburgh, PA 15215-1713 Resolutions Chairman Richard Rigatti 412-781-8131 Email: [email protected] Washington Liaison Jack A. -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Election Day — Documentary

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2020 Election Day — Documentary John Thomas Tarpley University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Film Studies Commons, Film Production Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Citation Tarpley, J. T. (2020). Election Day — Documentary. Theses and Dissertations Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3830 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Election Day — Documentary A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism by John Thomas Tarpley Lyon College Bachelor of Arts in English, 2010 July 2020 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council _________________________________ Colleen Thurston, M.F.A. Thesis Director _________________________________ _________________________________ Niketa Reed, M.A. Frank Milo Scheide, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT Election Day is a three-channel documentary chronicling the places, personalities, and tone of Little Rock, Arkansas, during its titular midterm Election Day in November 2018. Throughout the course of the day, the film branches across the city, capturing mini-narratives, bits of conversation, and tableau of civic activity in the public sphere. It is less concerned with the quantitative facts of the day as it is with conveying the transitory social expressions and moods of a modern, southern city on a uniquely American day. -

Fabienne Gouverneur

Fabienne Gouverneur 'PERSONAL, CONFIDENTIAL' Mike W. Fodor als Netzwerker und Kulturmittler Dissertation 2016 Andrássy Universität Budapest Interdisziplinäre Doktorschule der Andrássy Universität Leitung: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ellen Bos, Dr. habil. Georg Kastner Fakultät für Mitteleuropäische Studien Fabienne Gouverneur 'PERSONAL, CONFIDENTIAL' Mike W. Fodor als Netzwerker und Kulturmittler Betreuung: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Dieter A. Binder Disputationskommission: Prof. Dr. András Masát Prof. Dr. Walter Grünzweig Dr. habil. Georg Kastner Dr. Richard Lein Dr. Amália Kerekes Dr. Ibolya Murber Dr. Marcell Mártonffy Datum: 14.09.2016 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung..........................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Forschungsvorhaben – Stand der Forschung, Eingrenzung, Forschungsfragen........................4 1.2 Begriffsklärungen......................................................................................................................9 1.2.1 Netzwerk............................................................................................................................9 1.2.2 Grenzgänger.....................................................................................................................11 1.2.3 Kultur...............................................................................................................................12 1.3 Aufbau und Ziel der Arbeit......................................................................................................13 -

1927/28 - 2007 Гг

© Роман ТАРАСЕНКО. г. Мариуполь 2008г. Украина. [email protected] Лауреаты премии Американской Академии Киноискусства «ОСКАР». 1927/28 - 2007 гг. 1 Содержание Наменование стр Кратко о премии………………………………………………………. 6 1927/28г……………………………………………………………………………. 8 1928/29г……………………………………………………………………………. 9 1929/30г……………………………………………………………………………. 10 1930/31г……………………………………………………………………………. 11 1931/32г……………………………………………………………………………. 12 1932/33г……………………………………………………………………………. 13 1934г……………………………………………………………………………….. 14 1935г……………………………………………………………………………….. 15 1936г……………………………………………………………………………….. 16 1937г……………………………………………………………………………….. 17 1938г……………………………………………………………………………….. 18 1939г……………………………………………………………………………….. 19 1940г……………………………………………………………………………….. 20 1941г……………………………………………………………………………….. 21 1942г……………………………………………………………………………….. 23 1943г……………………………………………………………………………….. 25 1944г……………………………………………………………………………….. 27 1945г……………………………………………………………………………….. 29 1946г……………………………………………………………………………….. 31 1947г……………………………………………………………………………….. 33 1948г……………………………………………………………………………….. 35 1949г……………………………………………………………………………….. 37 1950г……………………………………………………………………………….. 39 1951г……………………………………………………………………………….. 41 2 1952г……………………………………………………………………………….. 43 1953г……………………………………………………………………………….. 45 1954г……………………………………………………………………………….. 47 1955г……………………………………………………………………………….. 49 1956г……………………………………………………………………………….. 51 1957г……………………………………………………………………………….. 53 1958г……………………………………………………………………………….. 54 1959г……………………………………………………………………………….. 55 1960г………………………………………………………………………………. -

Jack C. Ellis and Betsy A. Mclane

p A NEW HISTORY OF DOCUMENTARY FILM Jack c. Ellis and Betsy A. McLane .~ continuum NEW YOR K. L ONDON - Contents Preface ix Chapter 1 Some Ways to Think About Documentary 1 Description 1 Definition 3 Intellectual Contexts 4 Pre-documentary Origins 6 Books on Documentary Theory and General Histories of Documentary 9 Chapter 2 Beginnings: The Americans and Popular Anthropology, 1922-1929 12 The Work of Robert Flaherty 12 The Flaherty Way 22 Offshoots from Flaherty 24 Films of the Period 26 Books 011 the Period 26 Chapter 3 Beginnings: The Soviets and Political btdoctrinatioll, 1922-1929 27 Nonfiction 28 Fict ion 38 Films of the Period 42 Books on the Period 42 Chapter 4 Beginnings: The European Avant-Gardists and Artistic Experimentation, 1922-1929 44 Aesthetic Predispositions 44 Avant-Garde and Documentary 45 Three City Symphonies 48 End of the Avant-Garde 53 Films of the Period 55 Books on the Period 56 v = vi CONTENTS Chapter 5 Institutionalization: Great Britain, 1929- 1939 57 Background and Underpinnings 57 The System 60 The Films 63 Grierson and Flaherty 70 Grierson's Contribution 73 Films of the Period 74 Books on the Period 75 Chapter 6 Institutionalization: United States, /930- 1941 77 Film on the Left 77 The March of Time 78 Government Documentaries 80 Nongovernment Documentaries 92 American and British Differences 97 Denouement 101 An Aside to Conclude 102 Films of the Period 103 Books on the Period 103 Chapter 7 Expansion: Great Britain, 1939- 1945 105 Early Days 106 Indoctrination 109 Social Documentary 113 Records of Battle -

2021-22 CPS High School Guide

Welcome Your future awaits Cincinnati Public Schools 2021 2022 High School Guide 1 School Year Opening Doors to a World of Possibilities Hello CPS Students and Families, How to use this Guide This handy High School Guide will help you with the big Welcome to high school! decision: Which high school is best for me? Here in Cincinnati Public Cincinnati Public Schools offers 16 high schools with a variety of Schools, our high schools are programs that you can match to your interests and goals — and focused on preparing students which allow you to graduate prepared to enter college, the military for success — whether their or the workforce. paths take them to two- or Our high schools and program options are described inside. Study four-year colleges, into the this Guide with your family, and you’ll be ready to enter the online military or into the workforce. high school lottery. We’re making CPS a District of Destination — our families’ best choice for education. High School Application Lottery Period for 2021-22 Submit online applications to High School Lottery: We want our students to exceed Ohio’s rigorous graduation requirements, but we also want them graduating with clear plans January 12, 2021 through April 16, 2021 in their heads for their futures. How the online high school lottery works: • Select in order of preference, with We use an online lottery application to assign CPS students to three high schools number one being your top choice (in case your top choice high schools.* is filled). For lottery details and to see what each CPS high school offers, • The lottery assigns seats in high schools based on preference take some time to study this High School Guide as a family, order and space available. -

SLIFF Program 2006

CINEMA ST. LOUIS STAFF Executive Director Cliff Froehlich Artistic Director Chris Clark Operations Supervisor Mark Bielik table of CONTENTS Interns Tony Barsanti, Hillary Levine, Sarah Mayersohn, Andrew Smith Venue/Ticket Info 12 Volunteer Coordinators Jon-Paul Grosser, Kate Poss Marketing Consultant Cheri Hutchings Sidebars 13 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Special Events 15 President Jay L. Kanzler First Vice President/Secretary Delcia Corlew Awards 17 Second Vice President Carrie Houk Treasurer Barry Worth Sponsors 19 Volunteer Coordinators Jon-Paul Grosser, Kate Poss Board Members Jilanne Barnes, Patty Brandt, Film Descriptions 23 Kathy Corley, Georgia Frontiere, Joneal Joplin, Bobbie Lautenschlager, Cheresse Pentella, Documentaries 23 Eric Rhone, Jill Selsor, Jean Shepherd, Mary Strauss, Sharon Tucci, Jane von Kaenel, Scott Wibbenmeyer Features 32 ARTISTS Shorts 59 Program Cover/Poster Dan Zettwoch Filmmaker Awards Tom Huck Film Schedule 36 Trailer Animation Jeff Harris Award-winning purveyors of comics, books, apparel, toys and more. Proud sponsors of the 15th Annual St. Louis International Film Festival. 6392 Delmar in the Loop · 314.725.9110 · www.starclipper.com ST. LOUIS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 3 THE NEW CENTRAL WEST END LOUNGE FROM THE TEAM BEHIND THE PEPPER LOUNGE AND NECTAR... A HIGHER LEVEL OF NIGHTLIFE NOW OPEN LOCATED ON THE ROOFTOP ABOVE THE NEW CWE FOUNTAIN 44 MARYLAND PLAZA- CENTRAL WEST END WWW.MANDARINLOUNGE.NET SLAM ire FilmF 10.20R 10/20/06 11:26 AM Page 1 Through January 7 Discover a captivating story of ritual, sacrifice, and taboo told through com- pelling works of art created in the isolation of dramatic natural surroundings. Forest Park 314.721.0072 www.slam.org For information on exhibitions, films, and lectures visit www.slam.org. -

March 10-20, 2005

13th Annual 106 documentary, feature, animated, archival and children’s films Most screenings include discussion and are free Special Pre-Festival Event on March 1 MARCH 10-20, 2005 PHONE 202.342.2564 FAX 202.337.0658 EMAIL [email protected] WWW.DCENVIRONMENTALFILMFEST.ORG Staff Welcome to the 13th Annual Environmental Film Festival! Artistic Director & Founder: Flo Stone Today we are faced with a challenge that calls for a shift in our thinking, so that humanity stops Executive Director: Megan Newell threatening its life-support system. We are called to assist the Earth to heal her wounds and in the Associate Director & process heal our own – indeed, to embrace the whole creation in all its diversity, beauty and wonder. Children's Program: This will happen if we see the need to revive our sense of belonging to a larger family of life, with which Mary McCracken we have shared our evolutionary process. Associate Director: Georgina Owen — Prof. Wangari Maathai, 2004 Nobel Laureate (Peace) Public Relations Director: Helen Strong nce again this year we at the Environmental Film Festival in the Nation’s Capital have embarked on the Festival Assistant: Oexciting journey of presenting a diverse and engaging array of films from around the globe to challenge Ben McClenahan and broaden our audiences’ perception and understanding of the complex world that surrounds us. Festival Intern: Ivy Huo Over 11 days the festival will bring 106 films from 22 countries to audiences across the city with the Website: collaboration of nearly 60 partnering organizations. Half of the featured films (53) are premieres and Free Range Graphics, Shaw Thacher & Mary McCracken the festival will play host to a number of special guest speakers including 23 filmmakers, as well as many scientists, educators and cultural leaders. -

Congressional Record—Senate S10560

S10560 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE October 16, 2002 The Administration has been work- problem became painfully clear fol- facilitating the issuance of fraudulent ing to help create an international re- lowing the terrorist attacks of Sep- licenses, and call for the timely post- gime aimed at stopping the trade in tember 11, 2001, when we learned that a ing of convictions incurred in any conflict diamonds. Initiated by a group number of the terrorists had obtained State on the driver’s license. of African nations, the Kimberly proc- State-issued driver’s licenses or identi- Driver’s licenses are used by minors ess has the support of a diverse group fication cards using fraudulent docu- to purchase alcohol and cigarettes, by of non-governmental organizations and ments. criminals involved in identity theft, the diamond industry. Almost half the States have taken and for many other illegal purposes. In March 2002, the last full session of action since the terrorist attacks to Improving the security of the license is the Kimberly process was completed tighten licensing procedures and I am a matter of common sense. and has now reached a point where the encouraged that the National Gov- I am confident that this legislation individual countries involved need to ernors Association has formed a home- will provoke meaningful and lively de- pass implementing legislation. In the land security task force that, among bate, as well as more ideas about how United States, some modest legislation other things, will be working to deter- to approach driver’s license security. It may be enacted before the end of this mine the best way for States to may not be possible, given the press of year.