The Political Science 400: a 20-Year Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2

Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Sciences MA Level Course Syllabus 1. Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2. Spring Term COURSE DURATION 3. 6.0 ECTS 4. DISTRIBUTION OF HOURS Contact Hours • Lectures – 14 hours • Seminars – 12 hours • Midterm Exam – 2 hours • Final Exam – 2 hours • Research Project Presentation – 2 hours Independent Work - 118 hours Total – 150 hours 5. Nino Pavlenishvili INSTRUCTOR Associate Professor, PhD Ilia State University Mobile: 555 17 19 03 E-mail: [email protected] 6. None PREREQUISITES 7. Interactive lectures, topic-specific seminars with INSTRUCTION METHODS deliberations, debates, and group discussions; and individual presentation of the analytical memos, and project presentation (research paper and PowerPoint slideshow) 8. Within the course the students are to be introduced to COURSE OBJECTIVES the vast bulge of the literature on the causes of war and condition of peace. We pay primary attention to the theory and empirical research in the political science and international relations. We study the leading 1 theories, key concepts, causal variables and the processes instigating war or leading to peace; investigate the circumstances under which the outcomes differ or are very much alike. The major focus of the course is o the theories of interstate war, though it is designed to undertake an overview of the literature on civil war, insurgency, terrorism, and various types of communal violence and conflict cycles. We also give considerable attention to the methodology (qualitative/quantitative; small-N/large-N, Case Study, etc.) utilized in the well- known works of the leading scholars of the field and methodological questions pertaining to epistemology and research design. -

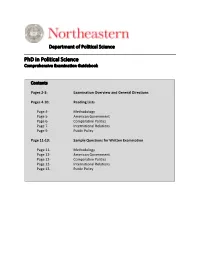

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Must War Find a Way?167

Richard K. Betts A Review Essay Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conict Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1999 War is like love, it always nds a way. —Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage tephen Van Evera’s book revises half of a fteen-year-old dissertation that must be among the most cited in history. This volume is a major entry in academic security studies, and for some time it will stand beside only a few other modern works on causes of war that aspiring international relations theorists are expected to digest. Given that political science syllabi seldom assign works more than a generation old, it is even possible that for a while this book may edge ahead of the more general modern classics on the subject such as E.H. Carr’s masterful polemic, 1 The Twenty Years’ Crisis, and Kenneth Waltz’s Man, the State, and War. Richard K. Betts is Leo A. Shifrin Professor of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University, Director of National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and editor of Conict after the Cold War: Arguments on Causes of War and Peace (New York: Longman, 1994). For comments on a previous draft the author thanks Stephen Biddle, Robert Jervis, and Jack Snyder. 1. E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 2d ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1946); and Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State, and War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959). See also Waltz’s more general work, Theory of International Politics (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979); and Hans J. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma?

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma? Robert Jervis xploring whether the Cold War was a security dilemma illumi- nates botEh history and theoretical concepts. The core argument of the security dilemma is that, in the absence of a supranational authority that can enforce binding agreements, many of the steps pursued by states to bolster their secu- rity have the effect—often unintended and unforeseen—of making other states less secure. The anarchic nature of the international system imposes constraints on states’ behavior. Even if they can be certain that the current in- tentions of other states are benign, they can neither neglect the possibility that the others will become aggressive in the future nor credibly guarantee that they themselves will remain peaceful. But as each state seeks to be able to pro- tect itself, it is likely to gain the ability to menace others. When confronted by this seeming threat, other states will react by acquiring arms and alliances of their own and will come to see the rst state as hostile. In this way, the inter- action between states generates strife rather than merely revealing or accentuat- ing con icts stemming from differences over goals. Although other motives such as greed, glory, and honor come into play, much of international politics is ultimately driven by fear. When the security dilemma is at work, interna- tional politics can be seen as tragic in the sense that states may desire—or at least be willing to settle for—mutual security, but their own behavior puts this very goal further from their reach.1 1. -

The Organizational Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms: Retrospect and Prospect Author(S): David A

The Organizational Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms: Retrospect and Prospect Author(s): David A. Welch Source: International Security , Fall, 1992, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Fall, 1992), pp. 112-146 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539170 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539170?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Security This content downloaded from 209.6.197.28 on Wed, 07 Oct 2020 15:39:26 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Organizational David A. Welch Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms Retrospect and Prospect 1991 marked the twentieth anniversary of the publication of Graham Allison's Essence of De- cision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. ' The influence of this work has been felt far beyond the study of international politics. Since 1971, it has been cited in over 1,100 articles in journals listed in the Social Sciences Citation Index, in every periodical touching political science, and in others as diverse as The American Journal of Agricultural Economics and The Journal of Nursing Adminis- tration. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Between Anarchy and Leviathan: A Return to Voluntarist Political Obligation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8pj296m6 Author Hallock, Emily Rachel Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Between Anarchy and Leviathan: A Return to Voluntarist Political Obligation A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Emily Rachel Hallock 2013 © Copyright by Emily Rachel Hallock 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Between Anarchy and Leviathan: A Return to Voluntarist Political Obligation by Emily Rachel Hallock Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Carole Pateman, Chair No defense of the liberal-democratic state can do without political obligation, yet existing theories cannot provide a successful account of political obligation. Existing accounts of obligation cannot parry critiques from rival theories, nor refute philosophical anarchists’ formidable attack on obligation. To move discussion of obligation forward, this dissertation offers an alternative solution to what George Klosko has called the ‘voluntarist paradox’ of liberal-democratic political obligation. While liberal ideas about the individual require that any obligation to obey be assumed through a voluntary act, individuals do not voluntarily assume obligations frequently enough to support legitimacy claims. In response to this paradox, most scholars deploy non-voluntary justifications for a general obligation to obey, while philosophical anarchists deny that such an obligation exists at all. In contrast, I argue that overcoming the voluntarist paradox requires a radically different view of the aims and scope of political obligation. -

Theory of International Politics

Theory of International Politics KENNETH N. WALTZ University of Califo rnia, Berkeley .A yy Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Reading, Massachusetts Menlo Park, California London • Amsterdam Don Mills, Ontario • Sydney Preface This book is in the Addison-Wesley Series in Political Science Theory is fundamental to science, and theories are rooted in ideas. The National Science Foundation was willing to bet on an idea before it could be well explained. The following pages, I hope, justify the Foundation's judgment. Other institu tions helped me along the endless road to theory. In recent years the Institute of International Studies and the Committee on Research at the University of Califor nia, Berkeley, helped finance my work, as the Center for International Affairs at Harvard did earlier. Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and from the Institute for the Study of World Politics enabled me to complete a draft of the manuscript and also to relate problems of international-political theory to wider issues in the philosophy of science. For the latter purpose, the philosophy depart ment of the London School of Economics provided an exciting and friendly envi ronment. Robert Jervis and John Ruggie read my next-to-last draft with care and in sight that would amaze anyone unacquainted with their critical talents. Robert Art and Glenn Snyder also made telling comments. John Cavanagh collected quantities of preliminary data; Stephen Peterson constructed the TabJes found in the Appendix; Harry Hanson compiled the bibliography, and Nacline Zelinski expertly coped with an unrelenting flow of tapes. Through many discussions, mainly with my wife and with graduate students at Brandeis and Berkeley, a number of the points I make were developed. -

Reading List for Comprehensive Examination in Political Theory

READING LIST FOR COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION IN POLITICAL THEORY Department of Political Science Columbia University Requirements Majors should prepare for questions based on reading from the entire reading list. Minors should prepare for questions based on reading from the core list and any one of the satellite lists. CORE LIST Plato, The Republic Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics Books I, II, V, VIII, X; Politics Polybius, Rise of the Roman Empire, Book I paragraphs 1-10 (“Introduction”) and Book VI Cicero, The Republic Augustine, City of God, Books I, VIII (ch.s 4-11), XII, XIV, XIX, XXII (ch.s 23-24, 29-30) Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Questions 42, 66, 90-92, 94-97, 105 Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince; Discourses (as selected in Selected Political Writings, ed. David Wootton) Jean Bodin, On Sovereignty (ed. Julian Franklin) Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (as selected in Norton Critical Edition, ed. David Johnston) James Harrington, Oceana (Cambridge U. Press, ed. J.G.A. Pocock), pp. 63-70 (from Introduction), pp. 161-87; 413-19 John Locke, Second Treatise of Government; “A Letter Concerning Toleration” David Hume, “Of the Original Contract,” “The Independence of Parliament,” “That Politics May Be Reduced to A Science,” “Of the First Principle of Government,” “Of Parties in General” 1 Montesquieu, Spirit of the Laws (as selected in Selected Political Writings, ed. Melvin Richter) Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Part I ("On the propriety of action"); Part II, Section II ("Of justice and beneficence"); Part IV ("On the effect of utility on the sentiment of approbation") Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on the Origins of Inequality; On The Social Contract Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (as selected in World’s Classics Edition, ed. -

Do Power-Sharing Institutions Work? Stable Democracy and Good

POWER-SHARING INSTITUTIONS – NORRIS 5/5/2005 8:44 AM Draft @ 5/5/2005 8:44 AM Words 16,687 Do power-sharing institutions work? Stable democracy and good governance in divided societies Pippa Norris McGuire Lecturer in Comparative Politics John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] www.pippanorris.com Synopsis: Consociational theory suggests that power-sharing institutions have many important consequences, not least that they are most likely to facilitate accommodation and cooperation among leadership elites, making them most suitable for states struggling to achieve stable democracy and good governance in divided societies. This study compares a broad cross-section of countries worldwide, including many multiethnic states, to investigate the impact of formal power-sharing institutions (PR electoral systems and federalism) on several indicators of democratic stability and good governance. The research demonstrates three main findings: (i) worldwide, power-sharing constitutions combining PR and federalism remain relatively rare (only 13 out of 191 states); (ii) federalism was found to be unrelated to any of the indicators of good governance under comparison; and (iii) PR electoral systems, however, were positively related to some indicators of good governance, both worldwide and in multiethnic states. This provides strictly limited support for the larger claims made by consociational theory. Nevertheless, the implications for policymakers suggest that investing in basic human development is a consistently more reliable route to achieve stable democracy and good governance than constitutional design alone. Paper for presentation at the Midwest Political Science Association annual convention, Panel 4-12 at 1.45-3.30pm on 9th April 2005, Palmer House Hilton, Chicago. -

JPS Volume 19 Issue 4 Cover and Back Matter

New in 1989- THEORETICAL POLITICS A New Quarterly Political Science Journal Edited by Richard Kimber University of Keele, Jan-Erik Lane University of Umea and Elinor Ostrom Indiana University The Journal of Theoretical Politics is a major new international journal, one of the principal aims of which is to foster the development of theory in the study of the political processes. It will provide a forum for the publication of original papers seeking to make genuinely theoretical contributions to the study of politics. The journal will include rigorous analytical articles on a range of theoretical topics. In particular it will focus on new theoretical work which is broadly accessible to social scientists and contributes to our understanding of political processes. It will also include original sysntheses of recent theoretical developments in diverse fields. The journal will not favour any specific theoretical perspective, but will emphasise the general importance of theory in political science. It will also encourage articles which evaluate the relative merits of competing theories to explain empirical phenomena. The Journal of Theoretical Politics will be published quarterly in January, April, July and October Subscription Rates, 1989 Institutional Individual one year £48.00($72.00) £22.00($33.00) two years £95.OO($I42.5O) £44.00($66.00) single copies £13.00(519.50) £6.00($9.00) SAGE Publications Ltd, 28 Banner Street, London EC IY 8QE SAGE Publications Ltd, PO Box 5096, Newbury Park, CA 91359, USA Cambridge Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought Edited by RAYMOND GEUSS, QUENTIN SKINNER and RICHARD TUCK This major new series will make available to students and teachers all the important texts required for an understanding of the history of political thought. -

APSA Contributors AS of NOVEMBER 10, 2014

APSA Contributors AS OF NOVEMBER 10, 2014 This list celebrates the generous contributions of our members in Jacobson Paul Allen Beck giving to one or more of the following programs from 1996 through 2014: APSA awards, programs, the Congressional Fellowship Pro- Cynthia McClintock John F. Bibby gram, and the Centennial Campaign. APSA thanks these donors for Ruth P. Morgan Amy B. Bridges ensuring that the benefi ts of membership and the infl uence of the Norman J. Ornstein Michael A. Brintnall profession will extend far into the future. APSA will update and print T.J. Pempel David S. Broder this list annually in the January issue of PS. Dianne M. Pinderhughes Charles S. Bullock III Jewel L. Prestage Margaret Cawley CENTENNIAL CIRCLE Offi ce of the President Lucian W. Pye Philip E. Converse ($25,000+) Policy Studies Organization J. Austin Ranney William J. Daniels Walter E. Beach Robert D. Putnam Ben F. Reeves Christopher J. Deering Doris A. Graber Ronald J Schmidt, Sr. Paul J. Rich Jorge I. Dominguez Pendleton Herring Smith College David B. Robertson Marion E. Doro Chun-tu Hsueh Endowment Janet D. Steiger for International Scholars Catherine E. Rudder Melvin J. Dubnick and Huang Hsing Kay Lehman Schlozman Eastern Michigan University Foundation FOUNDER’S CIRCLE ($5,000+) Eric J. Scott Leon D. Epstein Arend Lijphart Tony Affi gne J. Merrill Shanks Kathleen A. Frankovic Elinor Ostrom Barbara B. Bardes Lee Sigelman John Armando Garcia Beryl A. Radin Lucius J. Barker Howard J. Silver George J. Graham Leo A. Shifrin Robert H. Bates William O. Slayman Virginia H.