When Are Arms Races Dangerous? When Are Arms Races Charles L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report: the New Nuclear Arms Race

The New Nuclear Arms Race The Outlook for Avoiding Catastrophe August 2020 By Akshai Vikram Akshai Vikram is the Roger L. Hale Fellow at Ploughshares Fund, where he focuses on U.S. nuclear policy. A native of Louisville, Kentucky, Akshai previously worked as an opposition researcher for the Democratic National Committee and a campaign staffer for the Kentucky Democratic Party. He has written on U.S. nuclear policy and U.S.-Iran relations for outlets such as Inkstick Media, The National Interest, Defense One, and the Quincy Institute’s Responsible Statecraft. Akshai holds an M.A. in International Economics and American Foreign Policy from the Johns Hopkins University SAIS as well as a B.A. in International Studies and Political Science from Johns Hopkins Baltimore. On a good day, he speaks Spanish, French, and Persian proficiently. Acknowledgements This report was made possible by the strong support I received from the entire Ploughshares Fund network throughout my fellowship. Ploughshares Fund alumni Will Saetren, Geoff Wilson, and Catherine Killough were extremely kind in offering early advice on the report. From the Washington, D.C. office, Mary Kaszynski and Zack Brown offered many helpful edits and suggestions, while Joe Cirincione, Michelle Dover, and John Carl Baker provided much- needed encouragement and support throughout the process. From the San Francisco office, Will Lowry, Derek Zender, and Delfin Vigil were The New Nuclear Arms Race instrumental in finalizing this report. I would like to thank each and every one of them for their help. I would especially like to thank Tom Collina. Tom reviewed numerous drafts of this report, never The Outlook for Avoiding running out of patience or constructive advice. -

Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2

Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Sciences MA Level Course Syllabus 1. Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2. Spring Term COURSE DURATION 3. 6.0 ECTS 4. DISTRIBUTION OF HOURS Contact Hours • Lectures – 14 hours • Seminars – 12 hours • Midterm Exam – 2 hours • Final Exam – 2 hours • Research Project Presentation – 2 hours Independent Work - 118 hours Total – 150 hours 5. Nino Pavlenishvili INSTRUCTOR Associate Professor, PhD Ilia State University Mobile: 555 17 19 03 E-mail: [email protected] 6. None PREREQUISITES 7. Interactive lectures, topic-specific seminars with INSTRUCTION METHODS deliberations, debates, and group discussions; and individual presentation of the analytical memos, and project presentation (research paper and PowerPoint slideshow) 8. Within the course the students are to be introduced to COURSE OBJECTIVES the vast bulge of the literature on the causes of war and condition of peace. We pay primary attention to the theory and empirical research in the political science and international relations. We study the leading 1 theories, key concepts, causal variables and the processes instigating war or leading to peace; investigate the circumstances under which the outcomes differ or are very much alike. The major focus of the course is o the theories of interstate war, though it is designed to undertake an overview of the literature on civil war, insurgency, terrorism, and various types of communal violence and conflict cycles. We also give considerable attention to the methodology (qualitative/quantitative; small-N/large-N, Case Study, etc.) utilized in the well- known works of the leading scholars of the field and methodological questions pertaining to epistemology and research design. -

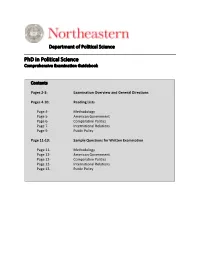

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Never Say Never Again Ariel E. Levite Nuclear Reversal Revisited

Never Say Never Again Never Say Never Again Ariel E. Levite Nuclear Reversal Revisited A serious gap exists in scholarly understanding of nuclear proliferation. The gap derives from inade- quate attention to the phenomena of nuclear reversal and nuclear restraint as well as insufªcient awareness of the biases and limitations inherent in the em- pirical data employed to study proliferation. This article identiªes “nuclear hedging” as a national strategy lying between nuclear pursuit and nuclear roll- back. An understanding of this strategy can help scholars to explain the nu- clear behavior of many states; it can also help to explain why the nightmare proliferation scenarios of the 1960s have not materialized. These insights, in turn, cast new light on several prominent proliferation case studies and the unique role of the United States in combating global proliferation. They have profound implications for engaging current or latent nuclear proliferants, underscoring the centrality of buying time as the key component of a non- proliferation strategy. The article begins with a brief review of contemporary nuclear proliferation concerns. It then takes stock of the surprisingly large documented universe of nuclear reversal cases and the relevant literature.1 It proceeds to examine the empirical challenges that bedeviled many of the earlier studies, possibly skew- ing their theoretical findings. Next, it discusses the features of the nuclear reversal and restraint phenomena and the forces that inºuence them. In this context, it introduces and illustrates an alternative explanation for the nu- clear behavior of many states based on the notion of nuclear hedging. It draws on this notion and other inputs to reassess the role that the United States At the time this article was written, Ariel E. -

Architecture in the Era of Terror: the Security Dilemma

Safety and Security Engineering 805 Architecture in the era of terror: the security dilemma G. Zilbershtein Department of Architecture, Texas A&M University, U.S.A. Abstract The growing public concern over the proliferation of terrorism has made protection of the physical environment of potential targets and terror interdiction a salient issue. The objective to secure the built environment against terrorism introduces a complex dilemma. At one level, the extent of investments in security in terms of cost-effectiveness is not proportional to the relatively rare threat of terrorism. Another level of the dilemma is rooted in the complex psychological implications of using security measures, that is, how to physically secure a building, while psychologically deter potential terrorists; more importantly is the question of how to accomplish those and yet not scare the users, i.e., the public. The latter part of the dilemma has been relatively ignored in the analysis of architectural measures against terrorism. And since catering to the psychological comfort of the users of the built environment has always been one of the greatest challenges of architecture, this paper focuses on that portion of the security dilemma of terrorism. Specifically, the study examines the threat characteristics and analyzes design recommendations that address the threat of terror for their contribution to the psychological comfort of the end users. Keywords: architecture, built environment, terrorism, risk assessment, security perception, security measures, design recommendations. 1 Introduction The post–cold war, as defined by John Lewis Gaddis [1], began with the collapse of one structure, the Berlin wall on November 9, 1989, and ended with the collapse of another, the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. -

Preparing for Nuclear War: President Reagan's Program

The Center for Defense Infomliansupports a strong eelens* but opposes e-xces- s~eexpenditures or forces It tetiev~Dial strong social, economic and political structures conifflaute equally w national security and are essential to the strength and welfareof our country - @ 1982 CENTER FOR DEFENSE INFORMATION-WASHINGTON, D.C. 1.S.S.N. #0195-6450 Volume X, Number 8 PREPARING FOR NUCLEAR WAR: PRESIDENT REAGAN'S PROGRAM Defense Monitor in Brief President Reagan and his advisors appear to be preparing the United States for nuclear war with the Soviet Union. President Reagan plans to spend $222 Billion in the next six years in an effort to achieve the capacity to fight and win a nuclear war. The U.S. has about 30,000 nuclear weapons today. The U.S. plans to build 17,000 new nuclear weapons in the next decade. Technological advances in the U.S. and U.S.S.R. and changes in nuclear war planning are major factors in the weapons build-up and make nuclear war more likely. Development of new U.S. nuclear weapons like the MX missile create the impression in the U.S., Europe, and the Soviet Union that the U.S.is buildinga nuclear force todestroy the Soviet nuclear arsenal in a preemptive attack. Some of the U.S. weapons being developed may require the abrogation of existing arms control treaties such as the ABM Treaty and Outer Space Treaty, and make any future agreements to restrain the growth of nuclear weapons more difficult to achieve. Nuclear "superiority" loses its meaning when the U.S. -

Coping with the Security Dilemma: a Fundamental Ambiguity of State Behaviour Andras Szalai Central European University

Volume 2 (2), 2009 AMBIGUITIES Coping with the Security Dilemma: A Fundamental Ambiguity of State Behaviour Andras Szalai Central European University Abstract he wording of international treaties, the language and actions of statesmen are often T ambiguous, even controversial. But there is a different, more fundamental ambiguity underlying international relations; one that is independent of human nature or the cognitive limitations of decision makers but instead results from the correct adjustment of state behaviour to the uncertainties of an anarchical international system. Due to the anarchical nature of the international system — the lack of a sovereign — states can only rely on their own strength for self-defence. But self-protection often threatens other states. If a state purchases armaments, even if it claims not to have aggressive intents, there is no sovereign to enforce these commitments and there is no way of being certain that the purchasing state is telling the truth, or that it will not develop such intents in the future. The so- called security dilemma has a number of effects on state behaviour. First, states often worry about implausible threats (see e.g. British defence plans against a possible French invasion in the 1930s) and/or get caught in arms races. Second, states develop an inherent mistrust in the language of the other, requiring commitments to be firm and unambiguous in order to be credible, since ambiguity invites conflicts and renders cooperation more difficult. Still, on the one hand, instead of a world of constant mistrust, we register instances of institutionalized inter-state cooperation. On the other hand, states often choose to make commitments that are deliberately ambiguous and outperform more transparent commitments. -

Must War Find a Way?167

Richard K. Betts A Review Essay Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conict Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1999 War is like love, it always nds a way. —Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage tephen Van Evera’s book revises half of a fteen-year-old dissertation that must be among the most cited in history. This volume is a major entry in academic security studies, and for some time it will stand beside only a few other modern works on causes of war that aspiring international relations theorists are expected to digest. Given that political science syllabi seldom assign works more than a generation old, it is even possible that for a while this book may edge ahead of the more general modern classics on the subject such as E.H. Carr’s masterful polemic, 1 The Twenty Years’ Crisis, and Kenneth Waltz’s Man, the State, and War. Richard K. Betts is Leo A. Shifrin Professor of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University, Director of National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and editor of Conict after the Cold War: Arguments on Causes of War and Peace (New York: Longman, 1994). For comments on a previous draft the author thanks Stephen Biddle, Robert Jervis, and Jack Snyder. 1. E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 2d ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1946); and Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State, and War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959). See also Waltz’s more general work, Theory of International Politics (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979); and Hans J. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma?

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma? Robert Jervis xploring whether the Cold War was a security dilemma illumi- nates botEh history and theoretical concepts. The core argument of the security dilemma is that, in the absence of a supranational authority that can enforce binding agreements, many of the steps pursued by states to bolster their secu- rity have the effect—often unintended and unforeseen—of making other states less secure. The anarchic nature of the international system imposes constraints on states’ behavior. Even if they can be certain that the current in- tentions of other states are benign, they can neither neglect the possibility that the others will become aggressive in the future nor credibly guarantee that they themselves will remain peaceful. But as each state seeks to be able to pro- tect itself, it is likely to gain the ability to menace others. When confronted by this seeming threat, other states will react by acquiring arms and alliances of their own and will come to see the rst state as hostile. In this way, the inter- action between states generates strife rather than merely revealing or accentuat- ing con icts stemming from differences over goals. Although other motives such as greed, glory, and honor come into play, much of international politics is ultimately driven by fear. When the security dilemma is at work, interna- tional politics can be seen as tragic in the sense that states may desire—or at least be willing to settle for—mutual security, but their own behavior puts this very goal further from their reach.1 1. -

Bizarre Star Andrew Zimmern Comes to the Beach

Island Times Volume IX,XIV, Number Number 10 9 PensacolaPensacola Beach,Beach, FloridaFlorida SeptemberAugust 21, 3, 20132018 BizarreBathtub Star Andrew Zimmern Racers Comes To The Beach Battle With A Paddle Look Inside for Tasty Times Special Section The Pensacola Beach Chamber has a recipe for success using star power and culinary talents to amp up the Sixth Annual Taste of the Beach, Saturday and Sun- Bathtubday, September racers will14 and raft 15 up at on Casino the soundfront Beach. Andrew starting Zimmern, line Sunday, center, isSeptember a James Beard 2 at 2 Award-winning p.m. Teams armed TV personality, with paddles chef, and food courage writer, teacherwill guide and unwieldy is widely flregarded oating bathtubs as one of around the most the versatile race course. and knowledgeable The winners personalities earn awards in andthe foodbragging world. rights He’s the as creator, the beach’s host and best co-executive bathtub captains. producer Beach of Travel School Channel’s PTA Vice-Presidenthit series, Bizarre Tasha Foods Tidwell with Andrew splashed Zimmern, her way Andrew around Zimmern’s the Bath Bizarre Tub race World, course, and hislast new year series, with her Bizarre deckhands Foods America. Kinley Tidwell, Zimmern left, will and be at Susie Taste Haag. of the Beach Saturday from 1 to 4 p.m. The festival, which showcases Pensacola Beach’s restaurants includes a dessert contest. Chef John Flaningam of Crab’s, top Theleft, proceedsearned fi rst from place the in Bathtub2012. His Races Bushwacker are donated Pie earned to Pensacola him a spot Beach in the fiElementary nals which willSchool. -

The Russian-A(Merican) Bomb: the Role of Espionage in the Soviet Atomic Bomb Project

J. Undergrad. Sci. 3: 103-108 (Summer 1996) History of Science The Russian-A(merican) Bomb: The Role of Espionage in the Soviet Atomic Bomb Project MICHAEL I. SCHWARTZ physicists and project coordinators ought to be analyzed so as to achieve an understanding of the project itself, and given the circumstances and problems of the project, just how Introduction successful those scientists could have been. Third and fi- nally, the role that espionage played will be analyzed, in- There was no “Russian” atomic bomb. There only vestigating the various pieces of information handed over was an American one, masterfully discovered by by Soviet spies and its overall usefulness and contribution Soviet spies.”1 to the bomb project. This claim echoes a new theme in Russia regarding Soviet Nuclear Physics—Pre-World War II the Soviet atomic bomb project that has arisen since the democratic revolution of the 1990s. The release of the KGB As aforementioned, Paul Josephson believes that by (Commissariat for State Security) documents regarding the the eve of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, Soviet sci- role that espionage played in the Soviet atomic bomb project entists had the technical capability to embark upon an atom- has raised new questions about one of the most remark- ics weapons program. He cites the significant contributions able and rapid scientific developments in history. Despite made by Soviet physicists to the growing international study both the advanced state of Soviet nuclear physics in the of the nucleus, including the 1932 splitting of the lithium atom years leading up to World War II and reported scientific by proton bombardment,7 Igor Kurchatov’s 1935 discovery achievements of the actual Soviet atomic bomb project, of the isomerism of artificially radioactive atoms, and the strong evidence will be provided that suggests that the So- fact that L.