The Russian-A(Merican) Bomb: the Role of Espionage in the Soviet Atomic Bomb Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 04 Newsletter

United States Atmospheric & Underwater Atomic Weapon Activities National Association of Atomic Veterans, Inc. 1945 “TRINITY“ “Assisting America’s Atomic Veterans Since 1979” ALAMOGORDO, N. M. Website: www.naav.com E-mail: [email protected] 1945 “LITTLE BOY“ HIROSHIMA, JAPAN R. J. RITTER - Editor April, 2012 1945 “FAT MAN“ NAGASAKI, JAPAN 1946 “CROSSROADS“ BIKINI ISLAND 1948 “SANDSTONE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “RANGER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1951 “GREENHOUSE“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1951 “BUSTER – JANGLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “TUMBLER - SNAPPER“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1952 “IVY“ ENEWETAK ATOLL 1953 “UPSHOT - KNOTHOLE“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1954 “CASTLE“ BIKINI ISLAND 1955 “TEAPOT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1955 “WIGWAM“ OFFSHORE SAN DIEGO 1955 “PROJECT 56“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1956 “REDWING“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1957 “PLUMBOB“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1958 “HARDTACK-I“ ENEWETAK & BIKINI 1958 “NEWSREEL“ JOHNSTON ISLAND 1958 “ARGUS“ SOUTH ATLANTIC 1958 “HARDTACK-II“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1961 “NOUGAT“ NEVADA TEST SITE 1962 “DOMINIC-I“ CHRISTMAS ISLAND JOHNSTON ISLAND 1965 “FLINTLOCK“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1969 “MANDREL“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1971 “GROMMET“ AMCHITKA, ALASKA 1974 “POST TEST EVENTS“ ENEWETAK CLEANUP ------------ “ IF YOU WERE THERE, YOU ARE AN ATOMIC VETERAN “ The Newsletter for America’s Atomic Veterans COMMANDER’S COMMENTS knowing the seriousness of the situation, did not register any Outreach Update: First, let me extend our discomfort, or dissatisfaction on her part. As a matter of fact, it thanks to the membership and friends of NAAV was kind of nice to have some of those callers express their for supporting our “outreach” efforts over the thanks for her kind attention and assistance. We will continue past several years. It is that firm dedication to to insure that all inquires, along these lines, are fully and our Mission-Statement that has driven our adequately addressed. -

Report: the New Nuclear Arms Race

The New Nuclear Arms Race The Outlook for Avoiding Catastrophe August 2020 By Akshai Vikram Akshai Vikram is the Roger L. Hale Fellow at Ploughshares Fund, where he focuses on U.S. nuclear policy. A native of Louisville, Kentucky, Akshai previously worked as an opposition researcher for the Democratic National Committee and a campaign staffer for the Kentucky Democratic Party. He has written on U.S. nuclear policy and U.S.-Iran relations for outlets such as Inkstick Media, The National Interest, Defense One, and the Quincy Institute’s Responsible Statecraft. Akshai holds an M.A. in International Economics and American Foreign Policy from the Johns Hopkins University SAIS as well as a B.A. in International Studies and Political Science from Johns Hopkins Baltimore. On a good day, he speaks Spanish, French, and Persian proficiently. Acknowledgements This report was made possible by the strong support I received from the entire Ploughshares Fund network throughout my fellowship. Ploughshares Fund alumni Will Saetren, Geoff Wilson, and Catherine Killough were extremely kind in offering early advice on the report. From the Washington, D.C. office, Mary Kaszynski and Zack Brown offered many helpful edits and suggestions, while Joe Cirincione, Michelle Dover, and John Carl Baker provided much- needed encouragement and support throughout the process. From the San Francisco office, Will Lowry, Derek Zender, and Delfin Vigil were The New Nuclear Arms Race instrumental in finalizing this report. I would like to thank each and every one of them for their help. I would especially like to thank Tom Collina. Tom reviewed numerous drafts of this report, never The Outlook for Avoiding running out of patience or constructive advice. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1994

1NS1DE: ^ Central and East European Coalition denounces U.S. foreign policy - page 3. ^ Book Review: Challenging Sudoplatovs account of Shukhevych's death - page 7. - Harvard Ukrainian Research institute summer seminar report - centerfold. О THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association inc., a fraternal non-profit association vol. LXII No. 40 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2,1994 75 cents American-Ukrainian Advisory Committee visits Kyyiv lMF to loan Ukraine $360 million by Marta Kolomayets production fields. Financing of the exist– Convenes meeting, issues communique Kyyiv Press Bureau ing deficit of the national budget and the balance of payments is practically impos– by Marta Kolomayets 24, the committee issued a 10-point com– KYYiv - Michel Camdessus, managing Kyyiv Press Bureau munique. The committee praised President sible without foreign sources, and the director of the international Monetary printing of additional money is the way Leonid Kuchma's "courageous decision to Fund, approved an economic recovery plan KYYiv - Reaffirming America's take charge of economic policy." to nowhere," said a statement issued by commitment to Ukraine's independence, for Ukraine that will release a loan of S360 Ukraine's prime minister, vitaliy Masol, "President ELeonidj Kravchuk always million by the end of the year, reported the members of the American-Ukrainian on Wednesday, September 28. avoided taking personal responsibility for Associated Press on September 29. Advisory Committee held their second "We hope the 1MF will implement its economic policy and so did President plenary meeting in Kyyiv last week. "This agreement promises to be a strong EBorisJ Yeltsin. President Kuchma is tak– commitments under the Economic Leaders such as Zbigniew Brzezinski first step in the direction of much-need– ing a step forward, which we applaud," Program and the memorandum, and that (U.S. -

Nonproliferation and Nuclear Forensics: Detailed, Multi- Analytical Investigation of Trinitite Post-Detonation Materials

SIMONETTI ET AL. CHAPTER 14: NONPROLIFERATION AND NUCLEAR FORENSICS: DETAILED, MULTI- ANALYTICAL INVESTIGATION OF TRINITITE POST-DETONATION MATERIALS Antonio Simonetti, Jeremy J. Bellucci, Christine Wallace, Elizabeth Koeman, and Peter C. Burns, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, 46544, USA e-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION (and ≤7% 240Pu), whereas it is termed “reactor fuel In 2010, the Joint Working Group of the grade” if the material consists >8% 240Pu. American Physical Society and the American Production of enriched U is costly and an energy- Association for the Advancement of Science defined intensive process, and the most widely used Nuclear Forensics as “the technical means by which processes are gaseous diffusion of UF6 (employed nuclear materials, whether intercepted intact or by the United States and France) and high- retrieved from post-explosion debris, are performance centrifugation of UF6 (e.g., Russia, characterized (as to composition, physical condition, Europe, and South Africa). The uranium processed age, provenance, history) and interpreted (as to under the “Manhattan Project” and used within the provenance, industrial history, and implications for device detonated over Hiroshima was produced by nuclear device design).” Detailed investigation of electromagnetic separation; the latter process was post-detonation material (PDM) is critical in ultimately abandoned in the late 1940s because of preventing and/or responding to nuclear-based its significant energy demands. The minimum terrorist activities/threats. However, accurate amount of fissionable material required for a nuclear identification of nuclear device components within reaction is termed its “critical mass”, and the value PDM typically requires a variety of instrumental depends on the isotope employed, properties of approaches and sample characterization strategies; materials, local environment, and weapon design the latter may include radiochemical separations, (Moody et al. -

ACDIS Occasional Paper

ACDIS FFIRS:3 1996 OCCPAP ACDIS Library ACDIS Occasional Paper Collected papers of the Ford Foundation Interdisciplinary Research Seminar on Pathological States ISpring 1996 Research of the Program in Arms Control, Disarmament, and International Security University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign December 1996 This publication is supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation and is produced by the Program m Arms Control Disarmament and International Security at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign The University of Illinois is an equal opportunity/ affirmative action institution ACDIS Publication Senes ACDIS Swords and Ploughshares is the quarterly bulletin of ACDIS and publishes scholarly articles for a general audience The ACDIS Occasional Paper series is the principle publication to circulate the research and analytical results of faculty and students associated with ACDIS Publications of ACDIS are available upon request Published 1996 by ACDIS//ACDIS FFIRS 3 1996 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 359 Armory Building 505 E Armory Ave Champaign IL 61820 Program ßfia Asma O esssrelg KJ aamisawE^ «««fl ^sôÊKïÂîMïnsS Secasnsy Pathological States The Origins, Detection, and Treatment of Dysfunctional Societies Collected Papers of the Ford Foundation Interdisciplinary Research Seminar Spring 1996 Directed by Stephen Philip Cohen and Kathleen Cloud Program m Arms Control Disarmament and International Security University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 359 Armory Building 505 East Armory Avenue Champaign IL 61820 ACDIS Occasional -

Trinity Scientific Firsts

TRINITY SCIENTIFIC FIRSTS THE TRINITY TEST was perhaps the greatest scientifi c experiment ever. Seventy-fi ve years ago, Los Alamos scientists and engineers from the U.S., Britain, and Canada changed the world. July 16, 1945 marks the entry into the Atomic Age. PLUTONIUM: THE BETHE-FEYNMAN FORMULA: Scientists confi rmed the newly discovered 239Pu has attractive nuclear Nobel Laureates Hans Bethe and Richard Feynman developed the physics fi ssion properties for an atomic weapon. They were able to discern which equation used to estimate the yield of a fi ssion weapon, building on earlier production path would be most effective based on nuclear chemistry, and work by Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls. The equation elegantly encapsulates separated plutonium from Hanford reactor fuel. essential physics involved in the nuclear explosion process. PRECISION HIGH-EXPLOSIVE IMPLOSION FOUNDATIONAL RADIOCHEMICAL TO CREATE A SUPER-CRITICAL ASSEMBLY: YIELD ANALYSIS: Project Y scientists developed simultaneously-exploding bridgewire detonators Wartime radiochemistry techniques developed and used at Trinity with a pioneering high-explosive lens system to create a symmetrically provide the foundation for subsequent analyses of nuclear detonations, convergent detonation wave to compress the core. both foreign and domestic. ADVANCED IMAGING TECHNIQUES: NEW FRONTIERS IN COMPUTING: Complementary diagnostics were developed to optimize the implosion Human computers and IBM punched-card machines together calculated design, including fl ash x-radiography, the RaLa method, -

Preparing for Nuclear War: President Reagan's Program

The Center for Defense Infomliansupports a strong eelens* but opposes e-xces- s~eexpenditures or forces It tetiev~Dial strong social, economic and political structures conifflaute equally w national security and are essential to the strength and welfareof our country - @ 1982 CENTER FOR DEFENSE INFORMATION-WASHINGTON, D.C. 1.S.S.N. #0195-6450 Volume X, Number 8 PREPARING FOR NUCLEAR WAR: PRESIDENT REAGAN'S PROGRAM Defense Monitor in Brief President Reagan and his advisors appear to be preparing the United States for nuclear war with the Soviet Union. President Reagan plans to spend $222 Billion in the next six years in an effort to achieve the capacity to fight and win a nuclear war. The U.S. has about 30,000 nuclear weapons today. The U.S. plans to build 17,000 new nuclear weapons in the next decade. Technological advances in the U.S. and U.S.S.R. and changes in nuclear war planning are major factors in the weapons build-up and make nuclear war more likely. Development of new U.S. nuclear weapons like the MX missile create the impression in the U.S., Europe, and the Soviet Union that the U.S.is buildinga nuclear force todestroy the Soviet nuclear arsenal in a preemptive attack. Some of the U.S. weapons being developed may require the abrogation of existing arms control treaties such as the ABM Treaty and Outer Space Treaty, and make any future agreements to restrain the growth of nuclear weapons more difficult to achieve. Nuclear "superiority" loses its meaning when the U.S. -

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry

J Radioanal Nucl Chem (2013) 298:993–1003 DOI 10.1007/s10967-013-2497-8 A multi-method approach for determination of radionuclide distribution in trinitite Christine Wallace • Jeremy J. Bellucci • Antonio Simonetti • Tim Hainley • Elizabeth C. Koeman • Peter C. Burns Received: 21 January 2013 / Published online: 13 April 2013 Ó Akade´miai Kiado´, Budapest, Hungary 2013 Abstract The spatial distribution of radiation within trin- The results from this study indicate that the device-related ititethinsectionshavebeenmappedusingalphatrack radionuclides were preferentially incorporated into the radiography and beta autoradiography in combination with glassy matrix in trinitite. optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Alpha and beta maps have identified areas of higher activity, Keywords Trinitite Á Nuclear forensics Á Radionuclides Á and these are concentrated predominantly within the surfi- Fission and activation products Á Laser ablation inductively cial glassy component of trinitite. Laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) analyses conducted at high spatial resolution yield weighted average 235U/238Uand240Pu/239Pu ratios of 0.00718 ± 0.00018 (2r) Introduction and 0.0208 ± 0.0012 (2r), respectively, and also reveal the presence of some fission (137Cs) and activation products Nuclear proliferation and terrorism are arguably the gravest (152,154Eu). The LA-ICP-MS results indicate positive cor- of threats to the security of any nation. The ability to relations between Pu ion signal intensities and abundances decipher forensic signatures in post-detonation nuclear of Fe, Ca, U and 137Cs. These trends suggest that Pu in debris is essential, both to provide a deterrence and to trinitite is associated with remnants of certain chemical permit a response to an incident. -

Space Race and Arms Race in the Western Media and the Czechoslovak Media

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Space Race and Arms Race in the Western Media and the Czechoslovak Media Bachelor thesis Brno 2017 Thesis Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Věra Gábová Annotation The bachelor thesis deals with selected Second World War and Cold War events, which were embodied in arms race and space race. Among events discussed are for example the first use of ballistic missiles, development of atomic and hydrogen bombs, launching the first artificial satellites etc. The thesis focuses on presentation of such events in the Czechoslovak and the Western press, compares them and also provides some historical facts to emphasize subjectivity in the media. Its aim is not only to describe the period as it is generally known, but to contrast the sources of information which were available at those times and to point out the nuances in the media. It explains why there are such differences, how space race and arms race are related and why the progress in science and technology was so important for the media. Key words The Second World War, the Cold War, space race, arms race, press, objectivity, censorship, propaganda 2 Anotace Tato bakalářská práce se zabývá některými událostmi druhé světové a studené války, které byly součástí závodu ve zbrojení a závodu v dobývání vesmíru. Mezi probíranými událostmi je například první použití balistických raket, vývoj atomové a vodíkové bomby, vypuštění první umělé družice Země atd. Práce se zaměřuje na prezentaci těchto událostí v Československém a západním tisku, porovnává je a také uvádí některá historická fakta pro zdůraznění subjektivity v médiích. -

May 2020 24 Soviet Intelligence on the Eve of the Great Patriotic

Volume 3, Issue 1: May 2020 Soviet Intelligence on the Eve of the Great Patriotic War Gaël-Georges Moullec (Rennes School of Business and Sorbonne Paris Nord University) Studying Soviet intelligence has long been a problem. On the one hand, academics, should it be by ideology or conformity, have historically avoided the question, refusing to see the originality of these services and their central place in the power system set up by the Bolsheviks. On the other hand, journalists and former Western services personnel repeatedly stressed the omnipotence of the “Organs” and their essential role in the alleged communist “world plot.” This was done without explaining why this supposed power system proved so ineffectual during the German lightning attack of June 1941 or, again, at the time of the collapse of the USSR in 1991.1 Today, the debate has been revived. Russian archives were opened at the end of the twentieth century, some partially or temporary, and many previously secret documents were published—often at the instigation of the new Russian intelligence services. One of the things that has clearly emerged from the archives is that probably the most significant event that impacted the Soviet intelligence services was the physical consequences of the 1937–1939 purges within the Soviet intelligence services, which resulted in the disappearance of the most experienced personnel. After the purges, the Soviet services had lost a sturdy portion of its workforce but retained access to a significant flow of information. The inability of the services to provide the country’s leadership with a clear analysis of the political and military situation in Germany and the imminence of the June 22, 1941, attack was therefore linked to new work practices resulting from this “purification.” In what follows, we discuss these developments at length. -

Espionage Against the United States by American Citizens 1947-2001

Technical Report 02-5 July 2002 Espionage Against the United States by American Citizens 1947-2001 Katherine L. Herbig Martin F. Wiskoff TRW Systems Released by James A. Riedel Director Defense Personnel Security Research Center 99 Pacific Street, Building 455-E Monterey, CA 93940-2497 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704- 0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DDMMYYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From – To) July 2002 Technical 1947 - 2001 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER Espionage Against the United States by American Citizens 1947-2001 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Katherine L. Herbig, Ph.D. Martin F. Wiskoff, Ph.D. 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

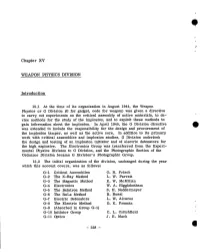

Weapon Physics Division

-!! Chapter XV WEAPON PHYSICS DIVISION Introduction 15.1 At the time of its organization in August 1944, the Weapon Physics or G Division (G for gadget, code for weapon) was given a directive to carry out experiments on the critical assembly of active materials, to de- vise methods for the study of the implosion, and to exploit these methods to gain information about the implosion. In April 1945, the G Division directive was extended to fnclude the responsibility for the design and procurement of the hnplosion tamper, as well as the active core. In addition to its primary work with critical assemblies and implosion studies, G Division undertook the design and testing of an implosion initiator and of electric detonators for the high explosive. The Electronics Group was transferred from the Experi- mental Physics Division to G Division, and the Photographic Section of the Ordnance Division became G Divisionts Photographic Group. 15.2 The initial organization of the division, unchanged during the year which this account covers, was as follows: G-1 Critical Assemblies O. R. Frisch G-2 The X-Ray Method L. W. Parratt G-3 The Magnetic Method E. W. McMillan G-4 Electronics W. A. Higginbotham G-5 The Betatron Method S. H. Neddermeyer G-6 The RaLa Method B. ROSSi G-7 Electric Detonators L. W. Alvarez G-8 The Electric Method D. K. Froman G-9 (Absorbed in Group G-1) G-10 Initiator Group C. L. Critchfield G-n Optics J. E. Mack - 228 - 15.3 For the work of G Division a large new laboratory building was constructed, Gamma Building.